Teaching in the Early Years of Practice: a Five-Year Longitudinal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

If You're Looking for Girl Power, You'll Find It at Moreton Hall

If you’re looking for girl power, you’ll find it at Moreton Hall A69377 Moretonian Magazine 2107_AW.pdf Page 1 of 94 Email: [email protected] Moreton Hall, Weston Rhyn, Telephone: (+44) 01691 773671 Oswestry, Shropshire Web: www.moretonhall.org SY11 3EW A69377 Moretonian Magazine 2107_AW.pdf Page 2 of 94 Contents 4 News Highlights 38 STEM 7 Special Awards Winners of 2017 40 Art Gallery 9 A day in the life of Jonathan Forster 44 A journalist covering under reported stories across Africa 10 Silver Service 46 Moreton’s Unsung Heroes 11 Carolyn Tilley 48 Duke of Edinburgh 12 Head Prefects’ Speeches 50 Creative Writing 14 Leavers’ Ball 2017 The Journey 17 Face2Face War 18 Little Shop of Horrors 52 Enrichment outside the classroom 19 Aladdin 54 Catering For The Masses 20 The Community Theatre 57 Classics 22 Performing Arts with Beth Clacher 58 Moreton Photography 24 Annual Investec Business Lunch 59 Sport 26 Moreton Enterprises 65 Moreton First 28 Enrichment Section News Highlights Bronwen The 3 R’s Jenner The Art Gallery 32 To My Remove Self Expressive Arts Sport 34 Careers at Moreton Hall 77 The Old Moretonian 36 Spoken English The Moretonian 2017 A69377 Moretonian Magazine 2107_AW.pdf Page 3 of 94 News Highlights Senior Mathematicians are Top 2% of the UK Moreton Hall’s team finished in the top 2% of the UK at the National Final of the Senior Team Maths Challenge in London, on 7th January. The team, comprised of Phoebe Jackson (U6), Pauline Ji (U6), Vinna Sun (L6) and Georgie Lang (L6) excelled. -

Year Five and Six Parents' Curriculum Meeting

St Joan of Arc RC Primary Year Two and Three Parents’ Curriculum Meeting F R I D A Y 4 TH OCTOBER Aims of the meeting Give you a better understanding of your child’s learning this term Share our aims Help parents/carers to feel empowered to support their children Give you the opportunity to ask questions Introductions Miss Newman– Year 2 and 3 lead. Behaviour lead Supporting classroom teachers Developing good classroom practice Monitoring pupil progress Part of the English and PE teams Homework - Reading At least 10-20 minutes daily in Year Two, and at least 20 minutes daily in Year Three. Signed reading record (comments are really helpful) Discussion about the text Sounding out and applying phonic knowledge Reading around the word Checking for understanding Predicting Inference and deduction Intonation and expression Comprehension cards Reading Records National Curriculum statements at front Signed off by teacher during guided reading Comment in book only if child not meet the statement in the lesson Ideas for home reading in the middle Homework - Reading Roy had waited a long time but nothing was happening. Then suddenly the line jerked. In his excitement he tripped over my bag and fell head first into the water. a. What was Roy doing before he fell? b. Why did he become excited? Homework - Reading By the time we reached the small village the sun was going down. After so long on the road we were glad to be able to take off our boots and rub our sore feet. a. What time of the day was it? b. -

Texans Getting Academically Prepared (Tgap)

TEXANS GETTING ACADEMICALLY PREPARED (TGAP) Year Six Evaluation Report September 2004 – August 2005 March 2006 Prepared for Texas Education Agency By Texas Center for Educational Research Center for Public Policy at the University of Houston TEXANS GETTING ACADEMICALLY PREPARED (TGAP) Year Six Evaluation Report September 2004 – August 2005 March 2006 Prepared for Texas Education Agency Prepared By Texas Center for Educational Research Center for Public Policy at the University of Houston ©Texas Center for Educational Research Credits Texas Center for Educational Research Contributing Authors The Texas Center for Educational Research Texas Center for Educational Research (TCER) conducts and communicates nonpartisan Kelly Shapley, Ph.D. research on education issues to serve as an Keith Sturges, MAA independent resource for those who make, Daniel Sheehan, Ed.D. influence, or implement education policy in Texas. A 15-member board of trustees governs the Center for Public Policy research center, including appointments from the at the University of Houston Texas Association of School Boards, Texas Gregory R. Weiher Association of School Administrators, and State Christina Hughes Board of Education. Joseph Howard For additional information about TCER research, please contact: Prepared for Kelly S. Shapley, Director Texas Center for Educational Research Texas Education Agency 12007 Research Blvd. 1701 N. Congress Avenue P.O. Box 679002 Austin, Texas 78701-1494 Austin, Texas 78767-9002 Phone: 512-463-9734 Phone: 512-467-3632 or 800-580-8237 Fax: 512-467-3658 Research Funded by Reports are available on the TCER Web Site at www.tcer.org Texas Education Agency Texans Getting Academically Prepared (TGAP) Year Six Executive Summary..................................................................................................................... -

Newly Qualified Social Workers in Scotland: a Five-Year Longitudinal Study

Newly qualified social workers in Scotland: A five-year longitudinal study Interim Report: December 2017 Scott Grant, Trish McCulloch, Martin Kettle, Lynn Sheridan, Stephen Webb December 2017 Funded by the Scottish Social Services Council 1 Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................... 4 Project Team ............................................................................ 5 Glossary ................................................................................... 6 Executive summary ................................................................. 7 Introduction ............................................................................. 10 (i) Overarching aim ............................................................... 10 (ii) Objectives ....................................................................... 10 (iii) Themes .......................................................................... 10 Method ................................................................................... 11 (i) Literature review .............................................................. 11 (ii) Online survey .................................................................. 11 (iii) Individual interviews ........................................................ 12 (iv) Focus groups .................................................................. 13 (v) Ethnography .................................................................... 14 Findings ................................................................................. -

(SSOG): Year Five Report

Nevada System of Higher Education Silver State Opportunity Grant (SSOG) Year 5 Report January 29, 2021 THE NEVADA SYSTEM OF HIGHER EDUCATION Board of Regents Dr. Mark W. Doubrava, Chair Mrs. Carol Del Carlo, Vice Chair Mr. Joseph C. Arrascada Mr. Patrick J. Boylan Mr. Byron Brooks Dr. Patrick R. Carter Ms. Amy J. Carvalho Dr. Jason Geddes Mrs. Cathy McAdoo Mr. Donald Sylvantee McMichael Sr. Mr. John T. Moran Ms. Laura E. Perkins Dr. Lois Tarkanian Officers of the Nevada System of Higher Education Dr. Melody Rose, Chancellor Dr. Keith Whitfield, President Mr. Brian Sandoval, President University of Nevada, Las Vegas University of Nevada, Reno Mr. Bart J. Patterson, President Dr. Federico Zaragoza, President Nevada State College College of Southern Nevada Ms. Joyce M. Helens, President Dr. Karin M. Hilgersom, President Great Basin College Truckee Meadows Community College Dr. Vincent R. Solis, President Dr. Kumud Acharya, President Western Nevada College Desert Research Institute 2 The Silver State Opportunity Grant Program Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................................. 4 BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................................. 6 ELIGIBILITY ........................................................................................................................................................................ -

Year Four Evaluation of Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation

Healthy Futures Year Four Evaluation of Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation BY THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA DEPARTMENT OF BEHAVIORAL HEALTH PREPARED BY: Anna E. Davis, BA Deborah F. Perry, PhD Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development 3300 Whitehaven Street, NW, Suite 3300 Washington, DC 20007 SEPTEMBER 30, 2014 Acknowledgements e want to acknowledge the ongoing contributions of Dr. Meghan Sullivan, program evaluator at the DC Department of Behavioral Health, for managing all of the data Wfrom the consultants in the field. We also appreciate the support of members of the Project LAUNCH team from the DC Departments of Health and Behavioral Health—especially Barbara Parks and Vinetta Freeman. Finally, we are grateful for the excellent work of the four mental health consultants as well as Dr. Shana Bellow who provides them with clinical and reflective supervision. HEALTHY FUTURES: YEAR FOUR EVALUATION 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................................................................1 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................................................5 Introduction ..............................................................................................................................................................................................7 The Evidence -

Early Years – Key Stage 4

Public Oral Health CURRIC ULUM TOOL KIT WWW... Early Years – Key Stage 4 Oral Health Promotion Team Derby City and Derbyshire County Public Contents • Introduction Page 2 • Oral Health messages Pages 3-5 • Oral Health links to the Early Years Foundation Stage Page 7 • Oral Health links to the National Curriculum: Key Stage 1 Page 9 • Oral Health links to the National Curriculum: Key Stage 2 Page 10 • Oral Health links to the National Curriculum: Key Stage 3 Page 11 • Oral Health links to the National Curriculum: Key Stage 4 Page 12 • Interactive Oral Health activities/ Downloadable resources: Early Years - Key Stage 4 Page 14 • Interactive Oral Health activities/ Downloadable resources: Special Educational Page 15 Needs and Disabilities and English as an Additional Language • Borrowing resources Page 16 • Purchasing Resources Page 17 • Apps available to download Page 18 1 Public Introduction Schools provide an important setting for promoting health which can easily be integrated into general health promotion, school curriculum and activities. Health promoting messages can be reinforced throughout the most influential stages of children’s lives, enabling them to develop lifelong sustainable attitudes, behaviours and skills. The health and wellbeing of school staff, families and community members can also be enhanced by programmes based in schools. Oral health is fundamental to general health and wellbeing. A healthy mouth enables an individual to speak, eat and socialize without experiencing active disease, discomfort or embarrassment. Poor oral health impacts on children’s confidence, language and personal, social and emotional development. Tackling poor oral health is a priority for Public Health England (PHE) under the national priority of ensuring that every child has the Best Start in Life. -

The Colour of Ritual, the Spice of Life: Faith, Fervour & Feeling

ZEST fESTival EducaTion pack 2014 THE COLOUR OF RITUAL, THE SPICE OF LIFE: FAITH, FERVOUR & FEELING The Zest festival was created in 2012 to celebrate the 300th anniversary of the Zuytdorp shipwreck and the cultural heritage of the dutch East india Trading company (VOC) in Western australia. Each year the Zest festival highlights the cultural contribution of a country along the VOC trading route. in 2014 we will focus on the countries now known as india, indonesia and Sri lanka, and their connections to the VOC and to Western australia. CONTENTS IMPLEMENTATION We encourage teachers to deliver these activities across implementation 3 term 3 2014, to coincide with the Zest festival on 20 and 21 September. Zest festival 2012 to 2016 5 Each page includes classroom activities, ranging from large new projects to small suggestions on integrating these Whole school activities 7 cultures into existing lessons. foundation to Year one 9 following each page of classroom activities is a list of content descriptions from the australian curriculum, coloured and ordered to follow http://www. TwoYear13 australiancurriculum.edu.au/ Year Three 17 English Historical context: Rituals and marriage 21 Mathematics Science Year four 23 History Historical context: Textiles 27 Geography Civics and Citizenship Year five 29 Economics and Business Historical context: Batavia 33 Arts Technologies Historical context: objects 33 Health and Physical Education Year Six 35 please note this is not an exhaustive list of activities or curriculum links, and we encourage teachers to assess or Historical context: colour 39 adjust the activities to suit their class. These activities have not been vetted and are used at the teacher’s discretion. -

Glasllwch Primary School Sex & Relationships Education (SRE) Policy

Glasllwch Primary School – SRE Policy Glasllwch Primary School Sex & Relationships Education (SRE) Policy This policy is a EAS Template Policy This policy is Statutory Key references WG Circular 019 / 2020 Staff Area / Subject Leader Chris Jackson Link Governor Stephen Morris Key Personnel in Policy Head Teacher, AENCo Training / Accreditation N/A Published / located GovernorWeb / School, HT office Aims of Policy: • To outline the functioning of the curriculum in school. Previous review date March 2017 Review date May 2019 Next review date May 2021 Reviewed by Policy committee Page 1 of 9 Glasllwch Primary School – SRE Policy Sex and Relationships Education (SRE) Policy SRE Sex and Relationships Education involves the delivery of lessons that aim to prepare all pupils for the opportunities, responsibilities and experiences of adult life, taking note of their moral spiritual, cultural, mental and physical development at school and in the world. Introduction This policy has been developed in line with guidance from the Welsh Assembly Government Circular No. 019/2010 (Sex and Relationships Education in Schools). Several other documents were also used to support the writing of this policy, including: ➢ The Sexual Health and Wellbeing in Wales Action Plan, 2010–2015 ➢ Education Act 1996 ➢ The requirements of the Personal and social education framework for 7 to 19-year-olds. ➢ AoLE for Health and Wellbeing Glasllwch Primary School actively participates in the Welsh Network of Healthy Schools Scheme (WNHSS). The WNHSS National Quality Award provides schools with a framework for the development of personal development and relationships. The Sexual Health and Wellbeing action plan for Wales 2010 - 2015 highlights the importance of school based SRE and the role that it plays in a child’s sexual health development and behaviour. -

The Annual Report of Her Majesty's Chief Inspector of Education and Training 2018-2019

Estyn Annual Report The Annual Report of Her Majesty's Chief Inspector of Education and Training in Wales 2018-2019 2 Contents 2-3 Contents Guide to the report 4-8 Foreword This year’s report is the 27th consecutive annual report published in Wales since the 9-65 Key themes in education reform Education (Schools) Act 1992 required its production. 10-12 Developing the curriculum The report consists of: 13-20 Developing skills The Chief inspector’s foreword 21-29 A high-quality education profession Section 1: A thematic section focusing on key themes in 30-33 Inspirational leaders education reform 33-43 Excellence, equality and wellbeing Section 2: Individual sector reports about inspection findings 44-51 Supporting a self-improving system in 2018-2019 52-65 Post-16 education and training Annex 1 provides an overview of the inspection framework and notes about the words, phrases and data used in the report. 66-156 Sector summaries Annex 2 provides a commentary 66-74 Non-school settings for children under five on the recently issued PISA 75-86 Primary schools findings for 2018. 87-98 Secondary schools Annex 3 sets out a series of charts showing Estyn’s inspection 99-103 Maintained all-age schools outcomes for 2018-2019. 104-107 Maintained special schools Annex 4 contains links to the documents referenced in the 108-112 Independent special schools report. 113-116 Independent mainstream schools 117-120 Independent specialist colleges 121-124 Pupil referral units 125-130 Local government education services 131-137 Further education 138-142 Work-based learning 143-145 Adult learning 146-149 Initial teacher education 150-151 Welsh for Adults 152-153 Careers 154-156 Learning in the justice sector 3 Contents 157-166 Annex 1: Overview 167-174 Annex 2: PISA 2018 findings 175-180 Annex 3: Inspection outcomes 2018-2019 181-190 Annex 3: List of references 4 Foreword Major reform Looking back over the last three years, the most striking features of the Welsh education system have been a set of fundamental reforms and the preparations made for those reforms. -

Mathematics and Physics Check Sheet Four Year Plan Major: Mathematics Minor: Secondary Education

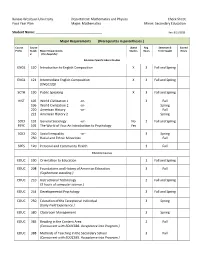

Kansas Wesleyan University Department: Mathematics and Physics Check Sheet Four Year Plan Major: Mathematics Minor: Secondary Education Student Name: _____________________________________ Rev. 8/31/2018 Major Requirements (Prerequisites in parentheses.) Course Course Liberal Req. Semester & Earned Prefix Numb Major Requirements Studies Hours Term Taught Hours er (Pre-Requisite) Education Specific Liberal Studies ENGL 120 Introduction to English Composition X 3 Fall and Spring ENGL 121 Intermediate English Composition X 3 Fall and Spring (ENGL120) SCTH 130 Public Speaking X 3 Fall and Spring HIST 105 World Civilization 1 -or- 3 Fall 106 World Civilization 2 -or- Spring 220 American History -or- Fall 221 American History 2 Spring SOCI 131 General Sociology -or- No 3 Fall and Spring PSYC 101 The World of You: An Introduction to Psychology Yes SOCI 240 Social Inequality -or- 3 Spring 250 Racial and Ethnic Minorities Fall SPES 120 Personal and Community Health 3 Fall Education Courses EDUC 100 Orientation to Education 1 Fall and Spring EDUC 208 Foundations and History of American Education 3 Fall (Sophomore standing.) EDUC 210 Instructional Technology 2 Fall and Spring (3 hours of computer science.) EDUC 244 Developmental Psychology 3 Fall and Spring EDUC 250 Education of the Exceptional Individual 3 Spring (Early Field Experience.) EDUC 380 Classroom Management 3 Spring EDUC 385 Reading in the Content Area 2 Fall (Concurrent with EDUC388. Acceptance into Program.) EDUC 388 Methods of Teaching in the Secondary School 3 Fall (Concurrent with -

Twenty Outstanding Primary Schools Excelling Against the Odds This Report Was Produced by Ofsted with Dr Peter Matthews, Consultant and Former Her Majesty’S Inspector

Twenty outstanding primary schools Excelling against the odds This report was produced by Ofsted with Dr Peter Matthews, consultant and former Her Majesty’s Inspector. © Crown copyright 2009 Contents Foreword 2 Pictures of success: the outstanding schools 59 Ash Green Primary School, Calderdale 60 Summary 3Banks Road Primary School, Liverpool 61 Berrymede Junior School, Ealing 62 Characteristics of outstanding primary Bonner Primary School, Tower Hamlets 63 schools in challenging circumstances 5 Cotmanhay Infant School, Derbyshire 64 Introduction 6 Cubitt Town Junior School, Tower Hamlets 65 Selecting the schools 6 Gateway Primary School, Westminster 66 Primary schools in challenging circumstances 8 John Burns Primary School, Wandsworth 67 Unearthing the secrets of success 9 Michael Faraday School, Southwark 68 Ramsden Infant School, Cumbria 69 St John the Divine Church of England Primary School, 11 Achieving excellence Lambeth 70 Raising attainment and achievement 12 St Monica’s Catholic Primary School, Sefton 71 Making teaching and learning consistently effective 13 St Paul’s Peel Church of England Primary School, Providing a broad, balanced, relevant and stimulating Salford 72 curriculum 15 St Sebastian’s Catholic Primary School and Nursery, Assessing and tracking progress 18 Liverpool 73 Attracting and appointing effective staff 20 Shiremoor Primary School, North Tyneside 74 Transformational leadership 20 Simonswood Primary School, Knowsley 75 From good to great 25 The Orion Primary School, Barnet 76 Welbeck Primary School, City of