Sullivan V. Lake Compounce Theme Park, Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quassy Wins Prestigious 'Turnstile Award' from Industry Publication

Quassy Wins Prestigious ‘Turnstile Award’ From Industry Publication BROOKLYN, N.Y. – Quassy Amusement & Waterpark, Middlebury, Conn., received one of the industry’s highest honors Saturday (Sept. 12, 2015) evening during the 2015 Golden Ticket Awards. Quassy, an iconic, family-owned property was the recipient of the 2015 Turnstile Award presented by Amusement Today (AT) Publisher Gary Slade during the gala event at Gargiulo’s Restaurant here. The Golden Ticket Awards are one the most prestigious honors within the amusement park industry and are compiled by the magazine, which has its offices in Arlington, Texas. In naming Quassy as one of his Publisher’s Picks for 2015, Slade noted that Quassy owners George Frantzis II and Eric Anderson have spent most of their lives at the lakeside property. “Today, both George Frantzis II and Eric Anderson oversee daily operations of the park and have been credited with the rebirth of the property and development of its new Splash Away Bay waterpark,” Slade said before presenting the award. “The two seasoned park owners set the stage in 2002 to rebuild itself with a $6 million multi- year redevelopment plan,” he added. The investment included the opening of the first phase of the waterpark in 2003 and led to the eventual building of its marquee attraction: Wooden Warrior roller coaster, which debuted in 2011. “Without their vision, Quassy – in operation since 1908 - could have met the fate of many New England parks of yesteryear and ceased to exist. But George Frantzis II and Eric Anderson did not let that happen. They reinvested and rebuilt to bring record revenues to Quassy, thus keeping the turnstile turning. -

Annual Meeting Edition NEAAPA Newsletter 2 Industry Icons to Be Inducted Into the NEAAPA Hall of Fame NASHUA, N.H

New England News 2020 Annual Meeting Edition NEAAPA Newsletter 2 Industry Icons To Be Inducted Into The NEAAPA Hall Of Fame NASHUA, N.H. – Industry icons James Patten III and the late Haig Gulezian will be inducted into the New England Association of Amuse- ment Parks and Attractions (NEAAPA) Hall of Fame on Tuesday, March 24. The gala event will take place during NEAAPA’s 107th Anniversary Edu- cation Conference & Annual Meeting at the Radisson Nashua Hotel here. Patten, a past secretary, vice presi- dent and president of NEAAPA, served as general manager at the for- mer Shaheen’s Fun Park, also referred to as Fun-O-Rama, in Salisbury Beach, Mass., while Gulezian was known as an entrepreneur in the amusement industry and had other James Patten III Haig Gulezian business ventures. Worked For Father-In-Law Inside This Issue Welcome To The Meeting Page 3 While attending Babson College in Massachusetts, James Patten III started working at the Salisbury Beach facility in 1965 for the SWT Program Page 3 late Roger J. Shaheen, owner of the amusement park. It was there IAAPA Show Floor Photos Pages 4-5 he met and married Shaheen’s daughter, Jilda. Powers In Hall Of Fame Page 7 Following his college graduation in 1967, James was named gen- Manufacturers News Pages 8-9-10 eral manager of the amusement park and was involved with the IAAPA Luncheon & Meeting Page 11 business until it closed in 1990. It was during his management stint Tom Morrow Dinner Page 12 that Shaheen’s facility evolved from a tiny business with one ride Jerry Brick Honored Page 13 and a couple of food stands into a full-fledged beachfront park. -

The Official Magazine of American Coaster Enthusiasts Rc! 127

FALL 2013 THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF AMERICAN COASTER ENTHUSIASTS RC! 127 VOLUME XXXV, ISSUE 1 $8 AmericanCoasterEnthusiasts.org ROLLERCOASTER! 127 • FALL 2013 Editor: Tim Baldwin THE BACK SEAT Managing Editor: Jeffrey Seifert uthor Mike Thompson had the enviable task of covering this year’s Photo Editor: Tim Baldwin Coaster Con for this issue. It must have been not only a delight to Associate Editors: Acapture an extraordinary convention in words, but also a source of Bill Linkenheimer III, Elaine Linkenheimer, pride as it is occurred in his very region. However, what a challenge for Jan Rush, Lisa Scheinin him to try to capture a week that seemed to surpass mere words into an ROLLERCOASTER! (ISSN 0896-7261) is published quarterly by American article that conveyed the amazing experience of Coaster Con XXXVI. Coaster Enthusiasts Worldwide, Inc., a non-profit organization, at 1100- I remember a week filled with a level of hospitality taken to a whole H Brandywine Blvd., Zanesville, OH 43701. new level, special perks in terms of activities and tours, and quite Subscription: $32.00 for four issues ($37.00 Canada and Mexico, $47 simply…perfect weather. The fact that each park had its own charm and elsewhere). Periodicals postage paid at Zanesville, OH, and an addition- character made it a magnificent week — one that truly exemplifies what al mailing office. Coaster Con is all about and why many people make it the can’t-miss event of the year. Back issues: RCReride.com and click on back issues. Recent discussion among ROLLERCOASTER! subscriptions are part of the membership benefits for our ROLLERCOASTER! staff American Coaster Enthusiasts. -

Lake Compounce Finalizes 2020 Schedule, Extends Season Passes Through 2021 Lake Compounce Family Theme & Water Park Will Conclude 2020 Season on Labor Day

MEDIA CONTACT: Amy Thomas [email protected] 860-583-3300 x6902 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Lake Compounce Finalizes 2020 Schedule, Extends Season Passes Through 2021 Lake Compounce Family Theme & Water Park will conclude 2020 season on Labor Day BRISTOL/SOUTHINGTON, CT – A roller coaster of a season at Lake Compounce will come to a close next month. Lake Compounce will finish its 2020 season with a final day of operations on Labor Day, Monday, September 7. To show appreciation for our Season Passholders’ support, Lake Compounce will extend all 2020 Silver, Gold & Gold Deluxe Season Passes to include the 2021 Season. “We are so grateful for our amazing team, as well as our guests, for adapting to these extraordinary times. Without their efforts, this year would not have been possible,” said Lake Compounce General Manager Larry Gorneault. “Our Team Members have been tireless in implementing enhanced health and safety measures to create the cleanest and safest environment possible for our guests. We’ll wrap up this season on a high note on Labor Day, and start getting ready for 2021.” The extension for 2020 Silver, Gold, and Gold Deluxe Season Passholders is automatic and will include the entire 2021 Summer Season. Extended Passholders will also be able to visit during Lake Compounce’s 2021 Halloween and Holiday events, which will not take place this year. Guests who previously purchased a 2021 Season Pass Extension will receive a credit equal to the price paid for the extension product. Beyond the return of the popular Haunted Graveyard and Holiday Lights events, Lake Compounce will celebrate its 175th anniversary in 2021 with the debut of the Venus Vortex water slide. -

Piolin Bidco Sustainability Report 2019

Sustainability Report 2019 Piolin BidCo S.A.U. and subsidiary companies Non-Financial Statement, pursuant to Law 11/2018 (Free translation from the original in Spanish. In the event of discrepancy, the Spanish-language version prevails) Versión: Draft- 1.0 Date of Report: 29.03.2020 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................ 3 ABOUT THIS REPORT ..........................................................................................................................................3 LETTER FROM THE CEO ......................................................................................................................................4 PIOLIN BIDCO AND THE PARQUES REUNIDOS GROUP ...................................................................................... 5 ABOUT US ........................................................................................................................................................5 OUR BUSINESS ..................................................................................................................................................6 ORGANISATIONAL OBJECTIVES AND STRATEGIES ......................................................................................................6 ETHICAL PRINCIPLES - OUR CODE OF CONDUCT .......................................................................................................7 OUR SUSTAINABILITY POLICY ...............................................................................................................................8 -

Parques Reunidos Servicios Centrales, S.A.U. and Subsidiaries

Parques Reunidos Servicios Centrales, S.A.U. and Subsidiaries. Consolidated Annual Accounts 30 September 2015 Consolidated Directors’ Report 2015 (With Independent Auditor's Report thereon) (Free translation from the original in Spanish. In the event of discrepancy, the Spanish-language version prevails.) KPMG Auditores S.L. Edificio Torre Europa Paseo de la Castellana, 95 28046 Madrid Independent Auditor's Report on the Consolidated Annual Accounts (Translation from the original in Spanish. In the event of discrepancy, the Spanish-language version prevails.) To the sole shareholder of Parques Reunidos Servicios Centrales, S.A.U. Report on the consolidated annual accounts We have audited the accompanying consolidated annual accounts of Parques Reunidos Servicios Centrales, S.A.U. (the “Company”) and its subsidiaries (the “Group”), which comprise the consolidated statement of financial position at 30 September 2015 and the consolidated income statement, consolidated statement of comprehensive income, consolidated statement of changes in equity and consolidated statement of cash flows for the year then ended, and consolidated notes. Directors' responsibility for the consolidated annual accounts The Directors are responsible for the preparation of the accompanying consolidated annual accounts in such a way that they present fairly the consolidated equity, consolidated financial position and consolidated financial performance of Parques Reunidos Servicios Centrales, S.A.U. in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards as adopted by the European Union (IFRS-EU), and other provisions of the financial reporting framework applicable to the Group in Spain and for such internal control that they determine is necessary to enable the preparation of consolidated annual accounts that are free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error. -

IAAPA Expo Press Conference 2019

IAAPA Expo Press Conference 2019 November 21st, 2019 This document is copyright and the proprietary information herein are the sole property of WhiteWater West industries ltd. And may not be reproduced or distributed without prior consent of whitewater west industries ltd. Contents 1 Welcome (Partners, Prizes, Projects) 2 Partnership News 3 Mobaro 4 RCI 5 Life Floor 6 Projects to Get Excited About 7 Recent Awards 5 Brass Ring Awards 2 Partners 3 Taking Adventure Play to the Next Level 4 WhiteWater & RCI collaboration WhiteWater has partnered with RCI to enhance Adventure Play products. Launching a new series of Adventure Play products based on No Boundaries called the Destination Series. RCI will manufacture and own the IP for the ‘Destination Series’, along with rights to WhiteWater’s Adventure Trail. 5 The New Destination Series Adventure Play Product Line Drag and drop Drag and drop Drag and drop Drag and drop image here image here image here image here Destination Series - Destination Series - Destination Series - Adventure Trail Amphitheatre Monument Stadium e title 6 Safety is non-negotiable at WhiteWater DUTY OF CARE MANAGEMENT ...TO TAKE BETTER CARE OF • Maintenance checks • Water quality • Safety and security checks • Facility management • Life safety systems • Incident reporting • Mechanical inspections • F&B checks Real-time centralised overview Construction Digital Discount After Sales (New Projects) Manuals NSF/ANSI 50 A brand-new standard to make splash pad surfaces even safer! Life Floor is the world’s first splash pad surface to meet the new safety standard. 10 Life Floor is the first surface to meet all of the six safety requirements set by NSF/ANSI 50 - Slip Resistance - Chemical Resistance - Impermeability - Impact Absorption - Cleanability - UV Resistance 11 Projects of Note 2019 and 2020 notable projects 12 13 SeaWorld Adventure Island Adventure Island, Tampa Bay introduces Solar Vortex™, America’s first Twin Tailspin water slide. -

Kennykon XIX the Pictures Tell the Story! All Photos by Steve Corbly, Except As Indicated

E Volume XVIII, Number 3 The Fun Times September 2008 September 2008 The FUNOFFICIAL Newsletter of the Western Pennsylvania Region KennyKon XIX The pictures tell the story! All photos by Steve Corbly, except as indicated Thunderbolt's 40th anniversary was celebrated during KennyKon XIX. The 201 attendees enjoyed morning ERT on the classic Vettel ride, and the inside of its helix served as the ideal spot for the group photo! continued on page 5 ACEwesternPA.org Page 1 The Fun Times September 2008 CHATTER! Happy Birthday to Elaine Linkenheimer, who turned On 70(!) in the later half of June and enjoyed a surprise party . Barry Kumpf, general manager of Lakemont Park can now say that he’s heard it all. In June, a guest requested a Trackwith the Editor refund because the ride lines were too short; apparently they felt that having to wait adds to the experience. Needless to Hello and welcome to The Fun Times 2008 fall say, their request was denied . congratulations to Greg edition. A lot has happened at local parks this year: Legowski on the purchase of his new home . condolences a new wood coaster at Waldameer Park, a new to Ken Carmichael and Pete Carmichael (who grew up interactive dark ride at Kennywood, and the sale of in ACE Western Pennsylvania, but now have careers and Kennywood Entertainment to Parques Reunidos of families elsewhere) on the death of their grandmother . Spain. While in some enthusiasts’ minds these may . speaking of Pete Carmichael, congratulations go out to be good or bad tidings of things to come, I feel that it him on his recent promotion to Director of Operations at will be for the best for our region. -

Golden Ticket Issue 2005

C M Y K SEPTEMBER 2005 B All about the BUSINESS of FUN! Amusement Today’s 2005 Golden Ticket Awards Tim Baldwin aware that it is more than just Amusement Today a business about hardware and ticket sales. It is finding Each summer Amusement that formula of providing the 2005 Today locates hundreds of customer with a great, enter- well-traveled enthusiasts to taining experience that makes form a “panel of experts” for them want to return over and our Golden Ticket Awards. over again. The heart and soul of the With each park capital- GOLDEN TICKET amusement park aficionado izing on its strengths and is peppered with devotion, improving in areas where admiration, and love for the they need to grow, our survey AWARDS industry. panel has a challenging task to Together, they can form a narrow their observations to a V.I.P. collective voice as they share single park that exceeds above their expertise and knowledge the rest. But when the parks BEST OF THE BEST! with us at Amusement Today, make it difficult for our par- and through us to the industry ticipants, the industry is truly and world at large. Originated headed in the right direction. in 1998, the Golden Ticket As witness to the monu- INSIDE Awards have since become mental experience of our sur- the “Oscars of the Amusement vey participants, parks from Industry,” and thanks to these eight countries outside of the PAGE 2 PAGE 11 PAGE 19 dedicated folk who continue U.S. can be found on our 2005 New Categories, Park & Ride Best Coasters of 2005 to share their time and effort, charts. -

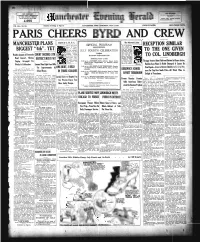

Yet Reception Similar to the One Given to Col J^Dbergh

'Tri' -■ I ^ f " v .. <:■.•■' iNET PRESS BUNl roMcaat %T O. S. WMtke* B«>cau . AVERAGE DAILT CERCCLATIOBf New Bares ^ ‘ ' j OF THE EVENING HERALD for the month of Jane, lWt7 Glondy today, possibly showers; 4 , 9 9 0 Sunday generally fair. (TWELVE PAGES) PRICE THREE CENTS VOL XU ., NO. 234. Classified AdTMtlslng on Page 10. MANCHESTER, CONN., SATURDAY, JULY 2, 1927. PARIS CHEERS AND C R E W MANCHESTER PLANS Chief of C. M. T. C. He Missed Little RECEPTION SIMILAR This is Brig.-Gen- CfFICIAL PROGRAM On a six-months’ James C. Rhea, trip around the MANCHESTER’S world, Felix War now at Boston, burg, the banker, BIGGEST “ 4th” . YET who has assumed i photoed here upon TO THE ONE GIVEN charge of all the ]ULY FOURTH CELEBRATION ! his retmrn to New Citizens' Military I York, saw every- Auspices j thing there was to •.k'.W.-.V.'.'.-.'.VA'. Training Camps Double Amount of Fireworks COURT DECIDES 5TH ' : Manchester Improvement Club. 1 see. He was in in the First Army nearly every coun TO COL J^DBERGH Corps Area. Gen try and witnessed Band Concert, Movies, eral Rhea served MONDAY, JULY 4,1927. fighting in China, DISTRICT MUST PAY a financial crisis two years overseas in Japan and talk Singing Arranged For and knows his 8:00 p .m .— CONCERT, Colt’s Armory Band, thirty Throngs Swarm About Railroad Station As Flyers Arrive; pieces, at the Playgrounds, on Oakland Street, ed with Soviet shrapnel. leaders in Moscow. Manchester. Monday's Celebration. Loomis Wins Fight Over Bills Warburg Balchen Says Plane So Badly Damaged It Cannot Be 9:00 p. -

Hclassifi Cation

Form No. 10-300 ^ \Q-"> ' UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Lake Compounce Carousel AND/OR COMMON LOCATION Uj rr/J" _ "- »- 1. STREET& NUMBER Lake Avenue _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN fyA- CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Southington ^_.VICINITY OF J£if^Elf~- Ronald Saras in STATE Connecticut CODE HartToTd ce°D^ HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC 2LOCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM i .BUILDING(S) X-PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED ^COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS X.OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X.YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION .•--.. _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: QOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME ' •'- Julian 'Norton et als STREET & NUMBER - • . r \S- Lake Avenue CITY. TOWN STATE Bristol VICINITY OF CT 06010 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. Southington Land Records, Town Hall STREET & NUMBER Main Street CITY. TOWN STATE Southington Connecticut REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE __COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED X_UNALTERED X-ORIGINALSITE —RUINS _ALTERED —MOVED DATE- —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Lake Compounce is a 2,000 foot long crystal clear lake located in a rural section of the northern part of the Town of Southington, Connecticut, a few feet south of the Bristol town line. On its northern shore is the Lake Compounce Amusement Park. -

Golden Ticket Issue 2003

and partnering with gettheloop.com For Immediate Release Contact: Gary Slade, Publisher, (817) 460-7220 August 23, 2003 Eric Minton, West Coast Bureau (520) 514-2254 ANNUAL AWARDS FOR AMUSEMENT, THEME AND WATERPARKS ANNOUNCED FOR 2003 PRESTIGIOUS POLL REVEALS THE “BEST OF THE BEST” IN THE AMUSEMENT INDUSTRY NEW BRAUNFELS, TEXAS—Among amusement and water parks, the best of the best are truly Golden. During a ceremony today at Schlitterbahn Waterpark Resort, Amusement Today, the leading amusement trade monthly, announced its annual Golden Ticket Awards with a few surprising new winners among traditional repeaters. The awards, based on surveys submitted by well-traveled park enthusiasts around the world, honor the top parks and rides as well as cleanest, friendliest and most efficient operations. New this year was the Publisher’s Pick chosen by Amusement Today Publisher Gary Slade. Winning the first-ever Publisher’s Pick is Gary and Linda Hays, owners of Cliff’s Amusement Park in Albuquerque, N.M., who last year took over construction of their wooden roller coaster, the New Mexico Rattler, after the manufacturer went bankrupt. The Hays’ therefore were able to keep the construction crew employed, pay suppliers and provide New Mexico it’s first major thrill ride as promised. Cedar Point in Sandusky, Ohio, repeated as the Best Park, and Schlitterbahn repeated as the Best Waterpark. Both parks have won these Golden Tickets in all six years of the awards. Other repeat winners were Holiday World & Splashin’ Safari in Santa Claus, Ind., as Friendliest Park and as Cleanest Park, Busch Gardens Williamsburg, Va., for Best Landscaping, Fiesta Texas in San Antonio for Best Shows, Knoebels Amusement Resort in Elysburg, Pa., for Best Food, Paramount’s Kings Island in Kings Mills, Ohio, for Best Kid’s Area and Cedar Point for Capacity.