Birds of the Same Feather Scratch Together

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Microworlds: Building Powerful Ideas in the Secondary School

US-China Education Review A 9 (2012) 796-803 Earlier title: US-China Education Review, ISSN 1548-6613 D DAVID PUBLISHING Microworlds: Building Powerful Ideas in the Secondary School Craig William Jenkins University of Wales, Wales, UK In the 1960s, the MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) developed a programming language called LOGO. Underpinning this invention was a profound new philosophy of how learners learn. This paper reviews research in the area and asks how one notion in particular, that of a microworld, may be used by secondary school educators to build powerful ideas in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) subjects. Keywords: microworlds, programming, STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics), constructionism, education Theories of Knowing This paper examines the microworld as a tool for acquiring powerful ideas in secondary education and explores their potential role in making relevant conceptual learning accessible through practical, constructionist approaches. In line with this aim, the paper is split into three main sections: The first section looks at the underlying educational theory behind microworlds in order to set up the rest of the paper; The second section critically examines the notion of a microworld in order to draw out the characteristics of a microworlds approach to learning; Finally, the paper ends with a real-world example of a microworld that is designed to build key, powerful ideas within a STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) domain of knowledge. To begin to understand the educational theory behind microworlds, a good starting point is to consider the ways in which learners interact with educational technology. In 1980, Robert Taylor (1980) provided a useful framework for understanding such interactions. -

The Education Column

The Education Column by Juraj Hromkovicˇ Department of Computer Science ETH Zürich Universitätstrasse 6, 8092 Zürich, Switzerland [email protected] Learn to Program?Program to Learn! Matthias Hauswirth Università della Svizzera italiana [email protected] Abstract Learning to program may make students more employable, and it may make them better thinkers. However, the most important reason for learning to program may well be that it enables an entirely new way of learning.1 1 Why Everyone Should Learn to Program We are in a gold rush in computer science education. Countless school districts, states, countries, non-profits, and startups rush to offer computer science, or cod- ing, for all. The goal—or gold?—too often is seen in empowering students to get great future-proof jobs. This first goal—programming to earn—is fine, but it is much too limited. A broader goal looks at computer science education as general education that helps students to become critical thinkers. Like the headmaster of my school, who recommended I study Latin because it would make me a better thinker. It probably did. And so did studying computer science. This second goal—programming to think—is great. However, I claim that there is a third, even greater, goal for teaching computer science to each and every person on the planet. Read on! 2 Computer Language as a Medium In “Computer Science: Reflections on the Field, Reflections from the Field” [6], Gerald Jay Sussman (MIT) writes an essay called “The Legacy of Computer Sci- ence.” There he cites from his own landmark programming textbook “Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs” (SCIP) [1]: 1 This article is based on a blog post previously published at https://medium.com/ @mathau/learning-to-program-programming-to-learn-c2c3d71d4d1d The computer revolution is a revolution in the way we think and in the way we express what we think. -

Co-Teaching Computer Science Across Borders

Session 3 L@S ’20, August 12–14, 2020, Virtual Event, USA Co-Teaching Computer Science Across Borders: Human-Centric Learning at Scale Chris Piech Lisa Yan Lisa Einstein Stanford University Stanford University Stanford University Stanford, CA, USA Stanford, CA, USA Stanford, CA, USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Ana Saavedra Baris Bozkurt Eliska Sestakova Stanford University Izmir Demokrasi Universitesi Czech Technical University Stanford, CA, USA Izmir, Turkey Prague, Czech Republic [email protected] [email protected] eliska.sestakova@fit.cvut.cz Ondrej Guth Nick McKeown Czech Technical University Stanford University Prague, Czech Republic Stanford, CA, USA ondrej.guth@fit.cvut.cz [email protected] ABSTRACT CCS Concepts Programming is fast becoming a required skill set for stu- •Social and professional topics ! Computing education; dents in every country. We present CS Bridge, a model for CS1; cross-border co-teaching of CS1, along with a correspond- ing open-source course-in-a-box curriculum made for easy INTRODUCTION localization. In the CS Bridge model, instructors and student- Computer science education has made substantial progress teachers from different countries come together to teach a towards the goal of CS for All in the United States, online, short, stand-alone CS1 course to hundreds of local high school and in some regions of the world. However, there is mounting students. The corresponding open-source curriculum has been evidence of a growing global digital divide, where access to specifically designed to be easily adapted to a wide variety of CS education is heavily dependant on which region you were local teaching practices, languages, and cultures. -

Polish Python: a Short Report from a Short Experiment Jakub Swacha Department of IT in Management, University of Szczecin, Poland [email protected]

Polish Python: A Short Report from a Short Experiment Jakub Swacha Department of IT in Management, University of Szczecin, Poland [email protected] Abstract Using a programming language based on English can pose an obstacle for learning programming, especially at its early stage, for students who do not understand English. In this paper, however, we report on an experiment in which higher-education students who have some knowledge of both Python and English were asked to solve programming exercises in a Polish-language-based version of Python. The results of the survey performed after the experiment indicate that even among the students who both know English and learned the original Python language, there is a group of students who appreciate the advantages of the translated version. 2012 ACM Subject Classification Social and professional topics → Computing education; Software and its engineering → General programming languages Keywords and phrases programming language education, programming language localization, pro- gramming language translation, programming language vocabulary Digital Object Identifier 10.4230/OASIcs.ICPEC.2020.25 1 Introduction As a result of the overwhelming contribution of English-speaking researchers to the conception and development of computer science, almost every popular programming language used nowadays has a vocabulary based on this language [15]. This can be seen as an obstacle for learning programming, especially at its early stage, for students whose native language is not English [11]. In their case, the difficulty of understanding programs is augmented by the fact that keywords and standard library function names mean nothing to them. Even in the case of students who speak English as learned language, they are additionally burdened with translating the words to the language in which they think. -

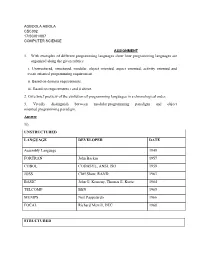

1. with Examples of Different Programming Languages Show How Programming Languages Are Organized Along the Given Rubrics: I

AGBOOLA ABIOLA CSC302 17/SCI01/007 COMPUTER SCIENCE ASSIGNMENT 1. With examples of different programming languages show how programming languages are organized along the given rubrics: i. Unstructured, structured, modular, object oriented, aspect oriented, activity oriented and event oriented programming requirement. ii. Based on domain requirements. iii. Based on requirements i and ii above. 2. Give brief preview of the evolution of programming languages in a chronological order. 3. Vividly distinguish between modular programming paradigm and object oriented programming paradigm. Answer 1i). UNSTRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE Assembly Language 1949 FORTRAN John Backus 1957 COBOL CODASYL, ANSI, ISO 1959 JOSS Cliff Shaw, RAND 1963 BASIC John G. Kemeny, Thomas E. Kurtz 1964 TELCOMP BBN 1965 MUMPS Neil Pappalardo 1966 FOCAL Richard Merrill, DEC 1968 STRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL 58 Friedrich L. Bauer, and co. 1958 ALGOL 60 Backus, Bauer and co. 1960 ABC CWI 1980 Ada United States Department of Defence 1980 Accent R NIS 1980 Action! Optimized Systems Software 1983 Alef Phil Winterbottom 1992 DASL Sun Micro-systems Laboratories 1999-2003 MODULAR LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL W Niklaus Wirth, Tony Hoare 1966 APL Larry Breed, Dick Lathwell and co. 1966 ALGOL 68 A. Van Wijngaarden and co. 1968 AMOS BASIC FranÇois Lionet anConstantin Stiropoulos 1990 Alice ML Saarland University 2000 Agda Ulf Norell;Catarina coquand(1.0) 2007 Arc Paul Graham, Robert Morris and co. 2008 Bosque Mark Marron 2019 OBJECT-ORIENTED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE C* Thinking Machine 1987 Actor Charles Duff 1988 Aldor Thomas J. Watson Research Center 1990 Amiga E Wouter van Oortmerssen 1993 Action Script Macromedia 1998 BeanShell JCP 1999 AngelScript Andreas Jönsson 2003 Boo Rodrigo B. -

Direct Manipulation of Turtle Graphics

Master Thesis Direct Manipulation of Turtle Graphics Matthias Graf September 30, 2014 Supervisors: Dr. Veit Köppen & Prof. Dr. Gunter Saake Otto-von-Guericke University Magdeburg Prof. Dr. Marian Dörk University of Applied Sciences Potsdam Abstract This thesis is centred around the question of how dynamic pictures can be created and manipulated directly, analogous to drawing images, in an attempt to overcome traditional abstract textual program representations and interfaces (coding). To explore new ideas, Vogo1 is presented, an experimental, spatially-oriented, direct manipulation, live programming environment for Logo Turtle Graphics. It allows complex abstract shapes to be created entirely on a canvas. The interplay of several interface design principles is demonstrated to encourage exploration, curiosity and serendipitous discoveries. By reaching out to new programmers, this thesis seeks to question established programming paradigms and expand the view of what programming is. 1http://mgrf.de/vogo/ 2 Contents 1 Introduction5 1.1 Research Question.................................6 1.2 Turtle Graphics..................................6 1.3 Direct Manipulation................................8 1.4 Goal......................................... 10 1.5 Challenges..................................... 12 1.6 Outline....................................... 14 2 Related Research 15 2.1 Sketchpad..................................... 15 2.2 Constructivism................................... 16 2.3 Logo........................................ 19 2.4 -

Why Design? Constructivism and Constructionism

When people think about learning and Why Design? education, they often think about one person transmitting information to an- Design projects engage kids as active participants, giving other, like this: them a greater sense of control and responsibility for the learning process. Design projects encourage creative problem-solving. Design projects are often interdisciplinary, bringing to- gether ideas from art, technology, math, and sciences. Design projects help kids learn to put themselves in the minds of others, since they need to consider how others will Increasingly, educators are recognizing use the things they create. that this “transmission approach” doesn’t work very well. Research has Design projects provide opportunities for reflection and shown that people learn best not when collaboration. they are passively receiving informa- tion, but when they are actively en- Design projects set up a positive-feedback loop of learning: gaged in exploring, experimenting, and when kids design things, they get new ideas, leading them expressing themselves (sometimes to design new things, from which they get even more ideas, known as the 3 X’s). leading them to design yet more things, and so on. More and more schools are focusing on learning-by-doing, engaging stu- dents in hands-on activities. Computer Clubhouses follow a similar strategy, Constructivism and Constructionism but go a step further: members don’t The Clubhouse learning-by-designing approach is inspired by simply get their hands on computers, two important theories of learning and education. they use computers to design, create, and invent things. It’s not just learning- The constructivist theory The constructionist approach by-doing; it’s learning-by-designing. -

Sep 1 4 2007 Libraries Rotch

SCRATCHR: A PLATFORM FOR SHARING USER-GENERATED PROGRAMMABLE MEDIA by Andr6s Monroy-Herndndez B.S. in Electronic Systems Engineering Instituto Tecnol6gico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey, 2001 Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences, School of Architecture and Planning, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September, 2007 @2007 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. Signature of Author: j Pro ramin Media Arts and Sciences August 20, 2007 Certified by: Mitchel Resnick LEGO Papert Professor of Learning Research, MIT Media Lab Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Prof . Deb Roy Chairman MASSACHUSETrS ISTT UTE Departmental Committee on Graduate Studies OF TECHNOLOGY SEP 1 4 2007 ROTCH LIBRARIES II 2 SCRATCHR: A PLATFORM FOR SHARING USER-GENERATED PROGRAMMABLE MEDIA by Andr6s Monroy-Hernandez B.S. in Electronic Systems Engineering Instituto Tecnol6gico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey, 2001 Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences, School of Architecture and Planning, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September, 2007 ABSTRACT This thesis presents the design and analysis of the Scratch Online Community. Scratch is a new programming language that enables kids to create programmable media such as games, interactive stories, animations, music and art. The Scratch Online Community was designed to be a source of inspirational ideas, provide an audience for children's creations and to foster collaboration among its members. The online community is powered by ScratchR: a social media platform. This work involved the creation of the ScratchR platform, the use of ScratchR to create the Scratch Online Community and the analysis of users' participation in the community. -

Eseecode: Creating a Computer Language from Teaching Experiences

Olympiads in Informatics, 2016, Vol. 10, 3–18 3 © 2016 IOI, Vilnius University DOI: 10.15388/ioi.2016.01 eSeeCode: Creating a Computer Language from Teaching Experiences Joan ALEMANY FLOS1, Jacobo VILELLA VILAHUR2 1Fundació Aula: 34 Av. Mare de Déu de Lorda, 08034 Barcelona Spain Explorium: Samalús 1 L3, 08530 La Garriga Spain eSeeCode.com 2Aula Escola Europea: 34 Av. Mare de Déu de Lorda, 08034 Barcelona Spain eSeeCode.com e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. It has been almost 50 years since the creation of Logo – one of the first educational programming languages. Although most people agreed that it was important to teach computa- tional thinking to children, only recently have school and district leaders begun to adopt curricula to include it – mainly through Scratch. In many cases this adoption has failed to provide the right methodologies and tools to teachers. In this paper, we analyse some of the different languages used in classrooms today and we propose an improved alternative that we have created – eSeeCode. We also share our experiences using this language in classrooms and how students can learn using this tool. Keywords: informatics curriculum, promoting informatics, programming language. 1. Overview Reading Papert’s Mindstorms: Children, Computers, and great ideas, one can have the feeling that we have not advanced much in the past 35 years (Papert, 1980). Many coun- tries are trying to include Coding as a required skill to learn in schools, either as a spe- cific subject or as part of a technology course. However, in many schools, teachers do not have the resources, materials and/or knowledge to bring computer science and cod- ing into the classroom. -

Digital Manipulatives.” These New Shape) Through Direct Manipulation of Physical Objects

Mitchel Resnick, Fred Martin, Robert Berg, Rick Borovoy, Vanessa Colella, Kwin Kramer, Brian Silverman MIT Media Laboratory 20 Ames Street Boston, MA 02139 USA +1 617 253 0330 {mres, rberg, borovoy, vanessa, khkramer, fredm, bss}@media.mit.edu http://el.www.media.mit.edu/groups/el/ ABSTRACT manipulation of abstract symbols, not physical objects. As In many educational settings, manipulative materials (such a result, these concepts are accessible only to older students, as Cuisenaire Rods and Pattern Blocks) play an important with more mathematical expertise. role in children’s learning, enabling children to explore This paper discusses a new breed of manipulative materials mathematical and scientific concepts (such as number and that we call “digital manipulatives.” These new shape) through direct manipulation of physical objects. Our manipulatives—with computational power embedded group at the MIT Media Lab has developed a new inside—are designed to expand the range of concepts that generation of “digital manipulatives”—computationally- children can explore through direct manipulation, enabling enhanced versions of traditional children’s toys. These new children to learn concepts that were previously considered manipulatives enable children to explore a new set of “too advanced” for children. The paper begins with a brief concepts (in particular, “systems concepts” such as feedback history of the educational uses of manipulative materials, and emergence) that have previously been considered “too then discusses several digital manipulatives that our advanced” for children to learn. In this paper, we discuss research group has developed. four of our digital manipulatives—computationally- augmented versions of blocks, beads, balls, and badges. LEARNING WITH MANIPULATIVE MATERIALS The idea that physical objects might play an important role Keywords in the learning process is a relatively new idea in the Education, learning, children, augmented reality history of education. -

Thinking in Levels: a Dynamic Systems Approach to Making Sense of the World

Thinking in Levels: A Dynamic Systems Approach to Making Sense of the World Uri Wilensky, Tufts University* Mitchel Resnick, MIT Media Lab* Published in Journal of Science Education and Technology, vol. 8, no. 1 (1999) Abstract The concept of emergent “levels” (i.e. levels that arise from interactions of objects at lower levels) is fundamental to scientific theory. In this paper, we argue for an expanded role for this concept of “levels” in the study of science. We show that confusion of levels (and “slippage” between levels) is the source of many deep misunderstandings about patterns and phenomena in the world. These misunderstandings are evidenced not only in students’ difficulties in the formal study of science but also in their misconceptions about experiences in their everyday lives. The StarLogo modeling language is designed as a medium for students to build models of multi-leveled phenomena and through these constructions explore the concept of levels. We describe several case studies of students working in StarLogo. The cases illustrate students’ difficulties with the concept of levels, and how they can begin to develop richer understandings. Introduction Two high-school students were writing a computer program to simulate the flow of traffic on a highway. They began by writing some simple rules for each car: Each car would accelerate if it didn’t see any other cars ahead of it, and it would slow down if it saw another car close ahead. They started the program running, and observed the patterns of traffic flow. On the screen, a traffic jam formed. They continued to watch and–much to their surprise–the jam started drifting backward along the highway. -

28 PLIERS: a Process That Integrates User-Centered Methods Into

PLIERS: A Process that Integrates User-Centered Methods into Programming Language Design MICHAEL COBLENZ, Carnegie Mellon University GAURI KAMBHATLA, University of Michigan PAULETTE KORONKEVICH, University of British Columbia JENNA L. WISE, Carnegie Mellon University CELESTE BARNABY, Facebook, Inc. JOSHUA SUNSHINE, JONATHAN ALDRICH, and BRAD A. MYERS, Carnegie Mellon University Programming language design requires making many usability-related design decisions. However, existing HCI methods can be impractical to apply to programming languages: languages have high iteration costs, programmers require significant learning time, and user performance has high variance. To address these problems, we adapted both formative and summative HCI methods to make them more suitable for program- ming language design. We integrated these methods into a new process, PLIERS, for designing programming languages in a user-centered way. We assessed PLIERS by using it to design two new programming languages. Glacier extends Java to enable programmers to express immutability properties effectively and easily. Obsid- ian is a language for blockchains that includes verification of critical safety properties. Empirical studies showed that the PLIERS process resulted in languages that could be used effectively by many programmers and revealed additional opportunities for language improvement. CCS Concepts: • Human-centered computing → User studies; Usability testing; User centered design;•Soft- ware and its engineering → Object oriented languages; Data types and structures; Additional Key Words and Phrases: Usability of programming languages, programming language design Gauri Kambhatla, Paulette Koronkevich, and Celeste Barnaby work conducted while at Carnegie Mellon University. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under grants CNS-1423054 and CCF- 1814826, by the U.S.