Scratch Community Blocks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hal Abelson Education: Princeton AB (Summa Cum Laude)

Hal Abelson Education: Princeton A.B. (summa cum laude) 1969 MIT Ph.D. (Mathematics) 1973 Professional Appointments: 1994–present MIT Class of 1922 Professor MIT 1991–present Full Professor of Computer Sci. and Eng. MIT 1982–1991 Associate Professor of Electrical Eng. and Computer Sci. MIT 1979–1982 Associate Professor, Dept. of EECS and Division for Study and Res. in Education MIT 1977–1979 Assistant Professor, Dept. of EECS and DSRE MIT 1974–1979 Lecturer, Dept. of Mathematics and DSRE MIT 1974–1979 Instructor, Dept. of Mathematics and DSRE MIT Selected publications relevant to this proposal: 1. “Transparent Accountable Data Mining: New Strategies for Privacy Protection,” with T. Berners- Lee, C. Hanson, J, Hendler, L. Kagal, D. McGuinness, G.J. Sussman, K. Waterman, and D. Weitzner. MIT CSAIL Technical Report, 2006-007, January 2006. 2. “Information Accountability,” with Daniel J. Weitzner, Tim Berners-Lee, Joan Feigenbaum, James Hendler, and Gerald Jay Sussman, MIT CSAIL Technical Report, 2007-034, June 2007. Available at http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/37600. 3. “The Creation of OpenCourseWare at MIT,” J. Science Education and Technology, May, 2007. 4. Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs, Hal Abelson, Gerald Jay Sussman and Julie Sussman, MIT Press and McGraw-Hill, 1985, (published translations in French, Polish, Chinese, Japanese, Spanish, and German). Second Edition, 1996. 5. “The Risks of Key Recovery, Key Escrow, and Trusted Third-Party Encryption,” with Ross Ander- son, Steven Bellovin, Josh Benaloh, Matt Blaze, Whitfield Diffie, John Gilmore, Peter Neumann, Ronald Rivest, Jeffrey Schiller, and Bruce Schneier, in World Wide Web Journal, vol. 2, no. -

Fostering Learning in the Networked World: the Cyberlearning Opportunity and Challenge

Inquiries or comments on this report may be directed to the National Science Foundation by email to: [email protected] “Any opinions, findings, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this report are those of the Task Force and do not necessarily reflect or represent the views of the National Science Foundation.” Fostering Learning in the Networked World: The Cyberlearning Opportunity and Challenge A 21st Century Agenda for the National Science Foundation1 Report of the NSF Task Force on Cyberlearning June 24, 2008 Christine L. Borgman (Chair), Hal Abelson, Lee Dirks, Roberta Johnson, Kenneth R. Koedinger, Marcia C. Linn, Clifford A. Lynch, Diana G. Oblinger, Roy D. Pea, Katie Salen, Marshall S. Smith, Alex Szalay 1 We would like to acknowledge and give special thanks for the continued support and advice from National Science Foundation staff Daniel Atkins, Cora Marrett, Diana Rhoten, Barbara Olds, and Jim Colby. Andrew Lau of the University of California at Los Angeles provided exceptional help and great spirit in making the distributed work of our Task Force possible. Katherine Lawrence encapsulated the Task Force’s work in a carefully crafted Executive Summary. Fostering Learning in the Networked World: The Cyberlearning Opportunity and Challenge A 21st Century Agenda for the National Science Foundation Science Foundation the National for A 21st Century Agenda Report of the NSF Task Force on Cyberlearning Table of Contents Executive Summary...............................................................................................................................................................................................................................5 -

A Critique of Abelson and Sussman Why Calculating Is Better Than

A critique of Abelson and Sussman - or - Why calculating is better than scheming Philip Wadler Programming Research Group 11 Keble Road Oxford, OX1 3QD Abelson and Sussman is taught [Abelson and Sussman 1985a, b]. Instead of emphasizing a particular programming language, they emphasize standard engineering techniques as they apply to programming. Still, their textbook is intimately tied to the Scheme dialect of Lisp. I believe that the same approach used in their text, if applied to a language such as KRC or Miranda, would result in an even better introduction to programming as an engineering discipline. My belief has strengthened as my experience in teaching with Scheme and with KRC has increased. - This paper contrasts teaching in Scheme to teaching in KRC and Miranda, particularly with reference to Abelson and Sussman's text. Scheme is a "~dly-scoped dialect of Lisp [Steele and Sussman 19781; languages in a similar style are T [Rees and Adams 19821 and Common Lisp [Steele 19821. KRC is a functional language in an equational style [Turner 19811; its successor is Miranda [Turner 1985k languages in a similar style are SASL [Turner 1976, Richards 19841 LML [Augustsson 19841, and Orwell [Wadler 1984bl. (Only readers who know that KRC stands for "Kent Recursive Calculator" will have understood the title of this There are four language features absent in Scheme and present in KRC/Miranda that are important: 1. Pattern-matching. 2. A syntax close to traditional mathematical notation. 3. A static type discipline and user-defined types. 4. Lazy evaluation. KRC and SASL do not have a type discipline, so point 3 applies only to Miranda, Philip Wadhr Why Calculating is Better than Scheming 2 b LML,and Orwell. -

The Computer As a Teaching Tool: Promising Practices. Conference Report (Cambridge, Massachusetts, July 12-13, 1984)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 295 g'6 IR 013 322 AUTHOR McDonald, Joseph P.; And Others TITLE The Computer as a Teaching Tool: Promising Practices. Conference Report (Cambridge, Massachusetts, July 12-13, 1984). CR85-10. INSTITUTION Educational Technology Center, Cambridge, MA. SPONS AGENCY Education Collaborative for Greater Boston, Inc., Cambridge, Mass. PUB DATE Apr 85 NOTE 25p.; For a report of a related conference, see IR 013 326. PUB TYPE Collected Works - Conference Proceedings (021) -- Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Computer Assisted Instruction; *Computer Literacy; Computer Simulation; Curriculum Development; Elementrry Secondary Education; *Language Arts; *Mathematics Instruction; Microcomputers; Professional Development; Research Needs; *Science Instruction; Teacher Education; Teacher Role IDENTIFIERS Reality ABSTRACT This report of a 1984 conference on the computer as a teaching tool provides summaries of presentations on the role of the computer in the teaching of science, mathematics, computer literacy, and language arts. Analyses of themes emerging from the conference are then presented under four headings: (1) The Computer and the Curriculum (the computer keeps learning connected to experience; the computer provides access to the underlying disciplines of subjects; the computer challenges the curricular status quo; and the computer aids implementation of the curriculum); (2) The Computer and Reality (computer-based models and simulations only imperfectly represent reality; a program may mask operations that students should experience to give depth and stability to their learning; and computers sometimes need to be used in conjunction with other, more concrete, experiences); (3) Perspectives on Teaching Practice (teaching is rooted in a teacher's own interests, need to understand, and social commitment; and teaching is, to a significant extent, a product of circumstance, not an entirely rational enterprise); and (4) Teachers' Professional Development (strategies and goals are needed for teacher training). -

Microworlds: Building Powerful Ideas in the Secondary School

US-China Education Review A 9 (2012) 796-803 Earlier title: US-China Education Review, ISSN 1548-6613 D DAVID PUBLISHING Microworlds: Building Powerful Ideas in the Secondary School Craig William Jenkins University of Wales, Wales, UK In the 1960s, the MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) developed a programming language called LOGO. Underpinning this invention was a profound new philosophy of how learners learn. This paper reviews research in the area and asks how one notion in particular, that of a microworld, may be used by secondary school educators to build powerful ideas in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) subjects. Keywords: microworlds, programming, STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics), constructionism, education Theories of Knowing This paper examines the microworld as a tool for acquiring powerful ideas in secondary education and explores their potential role in making relevant conceptual learning accessible through practical, constructionist approaches. In line with this aim, the paper is split into three main sections: The first section looks at the underlying educational theory behind microworlds in order to set up the rest of the paper; The second section critically examines the notion of a microworld in order to draw out the characteristics of a microworlds approach to learning; Finally, the paper ends with a real-world example of a microworld that is designed to build key, powerful ideas within a STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) domain of knowledge. To begin to understand the educational theory behind microworlds, a good starting point is to consider the ways in which learners interact with educational technology. In 1980, Robert Taylor (1980) provided a useful framework for understanding such interactions. -

The Education Column

The Education Column by Juraj Hromkovicˇ Department of Computer Science ETH Zürich Universitätstrasse 6, 8092 Zürich, Switzerland [email protected] Learn to Program?Program to Learn! Matthias Hauswirth Università della Svizzera italiana [email protected] Abstract Learning to program may make students more employable, and it may make them better thinkers. However, the most important reason for learning to program may well be that it enables an entirely new way of learning.1 1 Why Everyone Should Learn to Program We are in a gold rush in computer science education. Countless school districts, states, countries, non-profits, and startups rush to offer computer science, or cod- ing, for all. The goal—or gold?—too often is seen in empowering students to get great future-proof jobs. This first goal—programming to earn—is fine, but it is much too limited. A broader goal looks at computer science education as general education that helps students to become critical thinkers. Like the headmaster of my school, who recommended I study Latin because it would make me a better thinker. It probably did. And so did studying computer science. This second goal—programming to think—is great. However, I claim that there is a third, even greater, goal for teaching computer science to each and every person on the planet. Read on! 2 Computer Language as a Medium In “Computer Science: Reflections on the Field, Reflections from the Field” [6], Gerald Jay Sussman (MIT) writes an essay called “The Legacy of Computer Sci- ence.” There he cites from his own landmark programming textbook “Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs” (SCIP) [1]: 1 This article is based on a blog post previously published at https://medium.com/ @mathau/learning-to-program-programming-to-learn-c2c3d71d4d1d The computer revolution is a revolution in the way we think and in the way we express what we think. -

Co-Teaching Computer Science Across Borders

Session 3 L@S ’20, August 12–14, 2020, Virtual Event, USA Co-Teaching Computer Science Across Borders: Human-Centric Learning at Scale Chris Piech Lisa Yan Lisa Einstein Stanford University Stanford University Stanford University Stanford, CA, USA Stanford, CA, USA Stanford, CA, USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Ana Saavedra Baris Bozkurt Eliska Sestakova Stanford University Izmir Demokrasi Universitesi Czech Technical University Stanford, CA, USA Izmir, Turkey Prague, Czech Republic [email protected] [email protected] eliska.sestakova@fit.cvut.cz Ondrej Guth Nick McKeown Czech Technical University Stanford University Prague, Czech Republic Stanford, CA, USA ondrej.guth@fit.cvut.cz [email protected] ABSTRACT CCS Concepts Programming is fast becoming a required skill set for stu- •Social and professional topics ! Computing education; dents in every country. We present CS Bridge, a model for CS1; cross-border co-teaching of CS1, along with a correspond- ing open-source course-in-a-box curriculum made for easy INTRODUCTION localization. In the CS Bridge model, instructors and student- Computer science education has made substantial progress teachers from different countries come together to teach a towards the goal of CS for All in the United States, online, short, stand-alone CS1 course to hundreds of local high school and in some regions of the world. However, there is mounting students. The corresponding open-source curriculum has been evidence of a growing global digital divide, where access to specifically designed to be easily adapted to a wide variety of CS education is heavily dependant on which region you were local teaching practices, languages, and cultures. -

Computer Science Logo Style Beyond Programming

Computer Science Logo Style Beyond Programming Brian Harvey Computer Science Logo Style SECOND EDITION Volume 3 Beyond Programming The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England 1997 by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology The Logo programs in this book are copyright 1997 by Brian Harvey. These programs are free software; you can redistribute them and/or modify them under the terms of the GNU General Public License as published by the Free Software Foundation; either version 2 of the License, or (at your option) any later version. These programs are distributed in the hope that they will be useful, but WITHOUT ANY WARRANTY; without even the implied warranty of MERCHANTABILITY or FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. See the GNU General Public License (printed in the ®rst volume of this series) for more details. For information on program diskettes for PC and Macintosh, please contact the Marketing Department, The MIT Press, 55 Hayward Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 02142. Copyright credits for quoted material on page 349. This book was typeset in the Baskerville typeface. The cover art is an untitled mixed media acrylic monotype by San Francisco artist Jon Rife, copyright 1994 by Jon Rife and reproduced by permission of the artist. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Harvey, Brian, 1949± Computer Science Logo Style / Brian Harvey. Ð 2nd ed. p. cm. Includes indexes. Contents: v. 1. Symbolic computing. Ð v. 2. Advanced techniques Ð v. 3. Beyond programming. ISBN 0±262±58151±5 (set : pbk. : alk. paper). Ð ISBN 0±262±58148±5 (v. 1 : pbk. : alk. paper). Ð ISBN 0±262±58149±3 (v. -

Accessible Tools and Curricula for K-12 Computer Science Education

Accessible Tools and Curricula for K-12 Computer Science Education White paper from the Accessible Computer Science Education Fall Workshop (Draft for Review) November 17-19, 2020 Earl Huff, Clemson University Varsha Koushik, University of Colorado Richard E. Ladner, University of Washington Stephanie Ludi, University of North Texas Lauren Milne, Macalester College Aboubakar Mountapmbeme, University of North Texas Margaret Perkoff, University of Colorado Andreas Stefik, University of Nevada, Las Vegas Introduction Ladner Computer science is rapidly becoming an integral part of the K-12 school curriculum in the United States (US) and other countries. This white paper will focus on the US because we understand K-12 education better than in other countries. Since 1984, computer science has been part of the curriculum in schools that offered AP Computer Science A (CSA). This introduction to programming was originally taught using Pascal, then moved to C++ in 1999, and then Java in 2003. Since 2007, there has been a concerted effort by the National Science Foundation to bring computer science education to a much broader audience and to all levels in K-12. This includes all students regardless of gender, ethnicity, race, or disability. The effort began with Exploring Computer Science (ECS) which was a gentler introduction to computer science at the high school level. Shortly thereafter, the idea of an AP Computer Science Principles (CSP) course arose that was to be a gentler introduction to computer science than AP CSA with a college level equivalent, introductory computer science for non-majors. In 2016, AP CSP became a reality with 43,780 students taking the exam in spring 2017 and two years later that number rose to 94,361. -

Polish Python: a Short Report from a Short Experiment Jakub Swacha Department of IT in Management, University of Szczecin, Poland [email protected]

Polish Python: A Short Report from a Short Experiment Jakub Swacha Department of IT in Management, University of Szczecin, Poland [email protected] Abstract Using a programming language based on English can pose an obstacle for learning programming, especially at its early stage, for students who do not understand English. In this paper, however, we report on an experiment in which higher-education students who have some knowledge of both Python and English were asked to solve programming exercises in a Polish-language-based version of Python. The results of the survey performed after the experiment indicate that even among the students who both know English and learned the original Python language, there is a group of students who appreciate the advantages of the translated version. 2012 ACM Subject Classification Social and professional topics → Computing education; Software and its engineering → General programming languages Keywords and phrases programming language education, programming language localization, pro- gramming language translation, programming language vocabulary Digital Object Identifier 10.4230/OASIcs.ICPEC.2020.25 1 Introduction As a result of the overwhelming contribution of English-speaking researchers to the conception and development of computer science, almost every popular programming language used nowadays has a vocabulary based on this language [15]. This can be seen as an obstacle for learning programming, especially at its early stage, for students whose native language is not English [11]. In their case, the difficulty of understanding programs is augmented by the fact that keywords and standard library function names mean nothing to them. Even in the case of students who speak English as learned language, they are additionally burdened with translating the words to the language in which they think. -

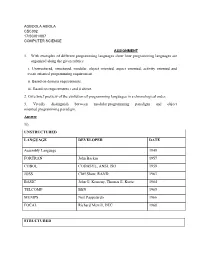

1. with Examples of Different Programming Languages Show How Programming Languages Are Organized Along the Given Rubrics: I

AGBOOLA ABIOLA CSC302 17/SCI01/007 COMPUTER SCIENCE ASSIGNMENT 1. With examples of different programming languages show how programming languages are organized along the given rubrics: i. Unstructured, structured, modular, object oriented, aspect oriented, activity oriented and event oriented programming requirement. ii. Based on domain requirements. iii. Based on requirements i and ii above. 2. Give brief preview of the evolution of programming languages in a chronological order. 3. Vividly distinguish between modular programming paradigm and object oriented programming paradigm. Answer 1i). UNSTRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE Assembly Language 1949 FORTRAN John Backus 1957 COBOL CODASYL, ANSI, ISO 1959 JOSS Cliff Shaw, RAND 1963 BASIC John G. Kemeny, Thomas E. Kurtz 1964 TELCOMP BBN 1965 MUMPS Neil Pappalardo 1966 FOCAL Richard Merrill, DEC 1968 STRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL 58 Friedrich L. Bauer, and co. 1958 ALGOL 60 Backus, Bauer and co. 1960 ABC CWI 1980 Ada United States Department of Defence 1980 Accent R NIS 1980 Action! Optimized Systems Software 1983 Alef Phil Winterbottom 1992 DASL Sun Micro-systems Laboratories 1999-2003 MODULAR LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL W Niklaus Wirth, Tony Hoare 1966 APL Larry Breed, Dick Lathwell and co. 1966 ALGOL 68 A. Van Wijngaarden and co. 1968 AMOS BASIC FranÇois Lionet anConstantin Stiropoulos 1990 Alice ML Saarland University 2000 Agda Ulf Norell;Catarina coquand(1.0) 2007 Arc Paul Graham, Robert Morris and co. 2008 Bosque Mark Marron 2019 OBJECT-ORIENTED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE C* Thinking Machine 1987 Actor Charles Duff 1988 Aldor Thomas J. Watson Research Center 1990 Amiga E Wouter van Oortmerssen 1993 Action Script Macromedia 1998 BeanShell JCP 1999 AngelScript Andreas Jönsson 2003 Boo Rodrigo B. -

Free As in Freedom (2.0): Richard Stallman and the Free Software Revolution

Free as in Freedom (2.0): Richard Stallman and the Free Software Revolution Sam Williams Second edition revisions by Richard M. Stallman i This is Free as in Freedom 2.0: Richard Stallman and the Free Soft- ware Revolution, a revision of Free as in Freedom: Richard Stallman's Crusade for Free Software. Copyright c 2002, 2010 Sam Williams Copyright c 2010 Richard M. Stallman Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.3 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled \GNU Free Documentation License." Published by the Free Software Foundation 51 Franklin St., Fifth Floor Boston, MA 02110-1335 USA ISBN: 9780983159216 The cover photograph of Richard Stallman is by Peter Hinely. The PDP-10 photograph in Chapter 7 is by Rodney Brooks. The photo- graph of St. IGNUcius in Chapter 8 is by Stian Eikeland. Contents Foreword by Richard M. Stallmanv Preface by Sam Williams vii 1 For Want of a Printer1 2 2001: A Hacker's Odyssey 13 3 A Portrait of the Hacker as a Young Man 25 4 Impeach God 37 5 Puddle of Freedom 59 6 The Emacs Commune 77 7 A Stark Moral Choice 89 8 St. Ignucius 109 9 The GNU General Public License 123 10 GNU/Linux 145 iii iv CONTENTS 11 Open Source 159 12 A Brief Journey through Hacker Hell 175 13 Continuing the Fight 181 Epilogue from Sam Williams: Crushing Loneliness 193 Appendix A { Hack, Hackers, and Hacking 209 Appendix B { GNU Free Documentation License 217 Foreword by Richard M.