Preface: RJP and the Rhythm and Blues Imagination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

En Vogue L at Oya C R O S S

- Left to Right: Tem inimus sequiae veriatem quam, estibus amet et aborerro offici de rest, quam, tendand uscienti ut FROM QUARTET TO TRIO, THE FUNKY DIVAS STILL SHOW (AND PROVE) THEY WERE BORN TO SING :EN VOGUE L AT OYA C R O S S APRIL/MAY 2017 EBONY.COM 83 lion YouTube views. But wait, there’s connection that goes into play when to learn each of more: The sultry songstresses climbed blending voices, one that Bennett came En Vogue members, from left, Rhona Bennett, the girls and re- the charts six times with singles “Hold equipped with, Ellis explains. Terry Ellis and Cindy Herron-Braggs spect the difer- On,” “My Lovin’ (Never Gonna Get “It’s being conscious of each other ences,” says El- It),” “Free Your Mind,” “Giving Him when we’re singing,” she says. “Where lis, the youngest THE SUPREMES.The Marvelettes. Something He Can Feel,” “Don’t Let is she placing her vibrato? What’s the of fve siblings. The Pointer Sisters. Between the 1960s Go,” and “Whatta Man” featuring tempo or how is she executing this song, “For me, that’s and the 1980s, the music scene was Salt-N-Pepa. this line or this word? I never thought freeing your dominated by timeless female groups. On top of their silky siren abilities, about it, but maybe that does come with mind. I think the But when it comes to girl group dynam- pop culture embraced the clingy red some seasoning and time. Rhona is a key is to under- ics, the 1990s are defned by En Vogue— dresses the vocally gifed women se- veteran as well, so she came in with that stand that you a foursome equipped with efortless duced viewers with in the music video information and awareness already. -

Hitmakers-1990-08-03

1-1 J ISSUE 649 fi(lG(1ST 3, 1990 55.00 an exclusive interview with L _ FOGELa President/CBS SHOW Industries I': 7d -. ~me co C+J 1M s-.0 1111, .. ^^-. f r 1 1 s rl Ji _ imp ii _U1115'11S The first hit single from the forthcoming album ALWAYS. Produced by L.A. Reid and Babyface for Laface, Inc. Management: Guilin Morey Associates .MCA RECORDS t 7990 MCA R,ords. S CUTTING EDGE LEADERSHIP FOR TODAY'S MUSIC RADIO Mainstream Top40 - Crossover Top40 - Rock - Alternative - Clubs/Imports - Retail ALDEN TO HEAD ELEKTRA PROMOTION Rick Alden has been National Marketing Manager, he was named Vice extremely good to me over the years, and I'm excited promoted to Senior Vice President of Top40 Promotion in November of 1987. about channeling my energies into this expanded President of Promotion Before joining ELEKTRA, Alden held positions at position. I'm working with the greatest staff, and we for ELEKTRA Entertain- ATLANTIC Records and RCA Records. are all looking forward to the future." ment, it was announced "After seeing the extraordinary results Rick has Also announced at ELEKTRA, by Vice President of this week by ELEKTRA achieved with Top40 Promotion, it became Urban Marketing and Promotion Doug Daniel, was Senior Vice Presi- increasingly clear that he was the man to head the appointment of Keir Worthy as National Director dent/General Manager Promotion overall," commented Hunt. "Rick's of Rap Promotion and Marketing. Brad Hunt. Alden was approach combines the analytic and the imaginative - Worthy previously served as Southwest/Midwest i previously Senior Vice he sees the big picture and never loses sight of the (See ALDEN page 40) RICK ALDEN President of Top40 details." Promotion, a post he Alden called his promotion "an honor and a was appointed to earlier this year. -

By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

A MODERN FAMILY: THE PERFORMANCE OF “FAMILY” AND FAMILIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION SERIES by Jennifer M. Fogel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Regina Morantz-Sanchez Associate Professor Bambi L. Haggins, Arizona State University © Jennifer M. Fogel 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan J. Douglas, Dr. Bambi L. Haggins, and Dr. Regina Morantz-Sanchez, who each contributed their time, expertise, encouragement, and comments throughout this entire process. These women who have mentored and guided me for a number of years have my utmost respect for the work they continue to contribute to our field. I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Amanda D. Lotz, who patiently refused to accept anything but my best work, motivated me to be a better teacher and academic, praised my successes, and will forever remain a friend and mentor. Without her constructive criticism, brainstorming sessions, and matching appreciation for good television, I would have been lost to the wolves of academia. One does not make a journey like this alone, and it would be remiss of me not to express my humble thanks to my parents and sister, without whom seven long and lonely years would not have passed by so quickly. They were both my inspiration and staunchest supporters. Without their tireless encouragement, laughter, and nurturing this dissertation would not have been possible. -

Emotions Newsletter Spring-Summer 2007

Newsletter Spring/Summer From the Chair’s Desk 2007 Dawn Robinson Volume 21, Number 1 University of Georgia Spring is here already and I am de- Council lighted to report that the Sociology of Emotion section is bustling with Chair: activity. The committees have been Dawn Robinson hard at work generating election University of Georgia slates, awarding honors, developing [email protected] what looks to be a very exciting pro- Committee were Lynn Smith-Lovin, gram at the annual meetings, and Duke University, Peggy Thoits, Uni- Chair-Elect: engaging in exceptional scholarship. versity of North Carolina-Chapel Viktor Gecas We have lots of news. Hill, and Doyle McCarthy, Fordham Purdue University University. Spencer contributed a [email protected] The intellectual vitality of emotions tremendous amount to our intellec- scholarship is evident throughout tual livelihood as a former Chair of Past Chair: the newsletter. Section members the Section, as editor of the top Patricia Adler have published several new books journal in our field, and as an ex- University of Colorado on emotions. In addition, there are emplary scholar of emotions. We [email protected] conferences dealing with emotions miss him greatly. We will have a Secretary-Treasurer: taking place all over the world this few opportunities to honor Spencer Linda Francis year. Please take a look at new Cahill at the New York meetings. SUNY-Stonybrook work by Amy Kroska presented in There will be a special memorial [email protected] our “Emotions Research” column, session in honor of Spencer co- edited by Alison Bianchi. sponsored by the Social Psychol- Council Members ogy Section, the Sociology of Emo- The nominations committee tions Section and the Society for Jennifer Lois (Thomas Scheff, Amy Wharton, the Study of Symbolic Interaction. -

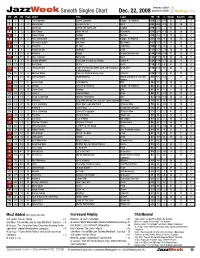

Jazzweek Smooth Singles Chart Dec

airplay data JazzWeek Smooth Singles Chart Dec. 22, 2008 powered by TW LW 2W Peak Artist Title Label TW LW +/- Weeks Reports Adds 1 1 1 1 Tim Bowman Sweet Sundays Trippin’ ’N’ Rhythm 309 333 -24 23 17 0 2 2 3 2 Warren Hill La Dolce Vita Koch 291 303 -12 22 16 0 3 4 4 1 Dave Koz Life In The Fast Lane Capitol 279 275 4 22 17 0 4 3 2 1 Eric Darius Goin’ All Out Blue Note 273 284 -11 34 18 0 5 5 5 5 Euge Groove Religify Narada 254 254 0 20 17 0 6 6 6 3 Paul Hardcastle Marimba Trippin ’N’ Rhythm 237 243 -6 28 15 0 7 10 7 7 Michael Lington You And I Nu Groove 157 147 10 14 16 0 8 11 14 8 Beyonce At Last Columbia 150 127 23 6 16 2 9 7 9 7 Wayne Brady Ordinary Peak 137 151 -14 18 16 0 10 8 11 8 Kenny G Tango Starbucks/Concord 136 150 -14 31 15 0 11 14 15 11 Nick Colionne No Limits Koch 132 114 18 23 18 0 12 9 8 8 Sergio Mendes The Look Of Love (w/ Fergie) Concord 126 149 -23 22 15 0 13 12 10 4 Earl Klugh Driftin’ Koch 119 127 -8 34 17 0 14 16 12 1 The Sax Pack Fallin’ For You (w/ Steve Cole, Jeff Kashiwa Shanachie 118 108 10 45 15 0 & Kim Waters) 15 15 16 8 Marcus Miller Free (w/ Corinne Bailey Rae) Concord 105 113 -8 52 13 0 16 13 13 13 John Legend Good Morning Home School/G.O.O.D./Co- 99 121 -22 7 15 0 lumbia 17 18 17 6 Jesse Cook Cafe Mocha EMI 96 95 1 38 12 0 18 24 22 18 Oli Silk Chill Or Be Chilled Trippin’ ’N’ Rhythm 85 82 3 12 16 0 18 21 28 19 Jesse Cook Havana EMI 85 85 0 4 10 2 20 20 20 1 Jessy J Tequila Moon Peak 84 94 -10 51 14 0 21 17 19 1 Brian Culbertson Always Remember GRP 83 102 -19 38 12 0 22 22 18 13 Al Green Stay With Me (By -

2018 Bounce Trumpet Awards Increases Viewership for the Second Consecutive Year, Seen by 2.4 Million Viewers Sunday Night

2018 Bounce Trumpet Awards Increases Viewership for the Second Consecutive Year, Seen by 2.4 Million Viewers Sunday Night Premiere Telecast Becomes #1 Show on Cable in African-American Homes ATLANTA (Feb. 13, 2018) – The 2018 Bounce Trumpet Awards was a big hit Sunday night, Feb. 11, racking up huge viewership gains and strong double-digit increases in the delivery of all key demos vs. last year’s telecast. The premiere of the 2018 Bounce Trumpet Awards was up +43% over last year’s telecast, delivering over half a million total viewers (546K), and posted significant double-digit gains of +38% in Households (398K), +60% in the delivery of Adults 18-49 (215K) and +27% in A25-54 (237K). This is the second consecutive year that the Bounce Trumpet Awards has grown in viewership; the 2017 telecast was up tremendously vs. 2016 as well. The 2018 Bounce Trumpet Awards aired on Bounce while being simulcast on sister networks Escape and Laff in honor of Black History Month. The airings across the three networks combined to reach 2.4 million total viewers. In the delivery of its target audience of African Americans (AA), the 2018 Bounce Trumpet Awards was the #1 show among all ad-supported cable networks in the delivery of AA Viewers 2+ in its premiere time-slot, beating such networks as Bravo, USA, OWN, BET, TV1 and over 100 other nets. The 2018 Bounce Trumpet Awards also beat BET’s Social Awards in Household delivery. The 2018 Bounce Trumpet Awards Red Carpet Show from 8:30-9:00 p.m. -

Images of Aggression and Substance Abuse in Music Videos : a Content Analysis

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research 2009 Images of aggression and substance abuse in music videos : a content analysis Monica M. Escobedo San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Escobedo, Monica M., "Images of aggression and substance abuse in music videos : a content analysis" (2009). Master's Theses. 3654. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.qtjr-frz7 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/3654 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMAGES OF AGGRESSION AND SUBSTANCE USE IN MUSIC VIDEOS: A CONTENT ANALYSIS A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Journalism and Mass Communications San Jose State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Monica M. Escobedo May 2009 UMI Number: 1470983 Copyright 2009 by Escobedo, Monica M. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

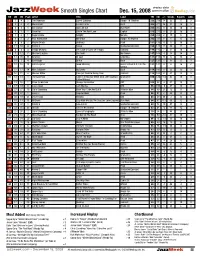

Jazzweek Smooth Singles Chart Dec

airplay data JazzWeek Smooth Singles Chart Dec. 15, 2008 powered by TW LW 2W Peak Artist Title Label TW LW +/- Weeks Reports Adds 1 1 4 1 Tim Bowman Sweet Sundays Trippin’ ’N’ Rhythm 333 319 14 22 17 0 2 3 3 2 Warren Hill La Dolce Vita Koch 303 277 26 21 18 0 3 2 2 1 Eric Darius Goin’ All Out Blue Note 284 284 0 33 18 0 4 4 1 1 Dave Koz Life In The Fast Lane Capitol 275 275 0 21 18 0 5 5 6 5 Euge Groove Religify Narada 254 248 6 19 17 0 6 6 5 3 Paul Hardcastle Marimba Trippin ’N’ Rhythm 243 235 8 27 15 0 7 9 9 7 Wayne Brady Ordinary Peak 151 138 13 17 16 0 8 11 10 8 Kenny G Tango Starbucks/Concord 150 123 27 30 17 0 9 8 8 8 Sergio Mendes The Look Of Love (w/ Fergie) Concord 149 142 7 21 18 3 10 7 12 7 Michael Lington You And I Nu Groove 147 148 -1 13 16 0 11 14 20 11 Beyonce At Last Columbia 127 112 15 5 13 2 11 10 7 4 Earl Klugh Driftin’ Koch 127 126 1 33 17 0 13 13 15 13 John Legend Good Morning Home School/G.O.O.D./Co- 121 121 0 6 16 2 lumbia 14 15 17 14 Nick Colionne No Limits Koch 114 106 8 22 15 0 15 16 11 8 Marcus Miller Free (w/ Corinne Bailey Rae) Concord 113 105 8 51 13 0 16 12 13 1 The Sax Pack Fallin’ For You (w/ Steve Cole, Jeff Kashiwa Shanachie 108 122 -14 44 16 0 & Kim Waters) 17 19 16 1 Brian Culbertson Always Remember GRP 102 93 9 37 15 0 18 17 19 6 Jesse Cook Cafe Mocha EMI 95 100 -5 37 12 0 19 27 27 19 Chris Standring Have Your Cake And Eat It Ultimate Vibe 94 69 25 12 15 3 19 20 23 1 Jessy J Tequila Moon Peak 94 91 3 50 15 0 21 28 39 21 Jesse Cook Havana EMI 85 59 26 3 13 5 22 18 14 13 Al Green Stay With Me (By The -

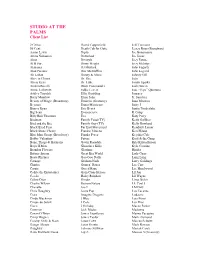

Client and Artist List

STUDIO AT THE PALMS Client List 2 Cellos David Copperfield Jeff Timmons 50 Cent Death Cab for Cutie Jersey Boys (Broadway) Aaron Lewis Diplo Joe Bonamassa Akina Nakamori Disturbed Joe Jonas Akon Divinyls Joey Fatone Al B Sure Dizzy Wright Joey McIntyre Alabama DJ Mustard John Fogarty Alan Parsons Doc McStuffins John Legend Ali Lohan Donny & Marie Johnny Gill Alice in Chains Dr. Dre JoJo Alicia Keys Dr. Luke Jordin Sparks Andrea Bocelli Duck Commander Josh Gracin Annie Leibovitz Eddie Levert Jose “Pepe” Quintano Ashley Tinsdale Ellie Goulding Journey Barry Manilow Elton John Jr. Sanchez Beauty of Magic (Broadway) Eminem (Grammy) Juan Montero Beyonce Ennio Morricone Juicy J Bianca Ryan Eric Benet Justin Timberlake Big Sean Evanescence K Camp Billy Bob Thornton Eve Katy Perry Birdman Family Feud (TV) Keith Galliher Bird and the Bee Family Guy (TV) Kelly Rowland Black Eyed Peas Far East Movement Kendrick Lamar Black Stone Cherry Frankie Moreno Keri Hilson Blue Man Group (Broadway) Franky Perez Keyshia Cole Bobby Valentino Future Kool & the Gang Bone, Thugs & Harmony Gavin Rossdale Kris Kristofferson Boyz II Men Ghostface Killa Kyle Cousins Brandon Flowers Gloriana Hinder Britney Spears Great Big World Lady Gaga Busta Rhymes Goo Goo Dolls Lang Lang Carnage Graham Nash Larry Goldings Charise Guns n’ Roses Lee Carr Cassie Gucci Mane Lee Hazelwood Cedric the Entertainer Gym Class Heroes Lil Jon Cee-lo Haley Reinhart Lil Wayne Celine Dion Hinder Limp Bizkit Charlie Wilson Human Nature LL Cool J Chevelle Ice-T LMFAO Chris Daughtry Icona Pop Los -

Song & Music in the Movement

Transcript: Song & Music in the Movement A Conversation with Candie Carawan, Charles Cobb, Bettie Mae Fikes, Worth Long, Charles Neblett, and Hollis Watkins, September 19 – 20, 2017. Tuesday, September 19, 2017 Song_2017.09.19_01TASCAM Charlie Cobb: [00:41] So the recorders are on and the levels are okay. Okay. This is a fairly simple process here and informal. What I want to get, as you all know, is conversation about music and the Movement. And what I'm going to do—I'm not giving elaborate introductions. I'm going to go around the table and name who's here for the record, for the recorded record. Beyond that, I will depend on each one of you in your first, in this first round of comments to introduce yourselves however you wish. To the extent that I feel it necessary, I will prod you if I feel you've left something out that I think is important, which is one of the prerogatives of the moderator. [Laughs] Other than that, it's pretty loose going around the table—and this will be the order in which we'll also speak—Chuck Neblett, Hollis Watkins, Worth Long, Candie Carawan, Bettie Mae Fikes. I could say things like, from Carbondale, Illinois and Mississippi and Worth Long: Atlanta. Cobb: Durham, North Carolina. Tennessee and Alabama, I'm not gonna do all of that. You all can give whatever geographical description of yourself within the context of discussing the music. What I do want in this first round is, since all of you are important voices in terms of music and culture in the Movement—to talk about how you made your way to the Freedom Singers and freedom singing. -

ANSAMBL ( [email protected] ) Umelec

ANSAMBL (http://ansambl1.szm.sk; [email protected] ) Umelec Názov veľkosť v MB Kód Por.č. BETTER THAN EZRA Greatest Hits (2005) 42 OGG 841 CURTIS MAYFIELD Move On Up_The Gentleman Of Soul (2005) 32 OGG 841 DISHWALLA Dishwalla (2005) 32 OGG 841 K YOUNG Learn How To Love (2005) 36 WMA 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Dance Charts 3 (2005) 38 OGG 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Das Beste Aus 25 Jahren Popmusik (2CD 2005) 121 VBR 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS For DJs Only 2005 (2CD 2005) 178 CBR 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Grammy Nominees 2005 (2005) 38 WMA 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Playboy - The Mansion (2005) 74 CBR 841 VANILLA NINJA Blue Tattoo (2005) 76 VBR 841 WILL PRESTON It's My Will (2005) 29 OGG 841 BECK Guero (2005) 36 OGG 840 FELIX DA HOUSECAT Ft Devin Drazzle-The Neon Fever (2005) 46 CBR 840 LIFEHOUSE Lifehouse (2005) 31 OGG 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS 80s Collection Vol. 3 (2005) 36 OGG 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Ice Princess OST (2005) 57 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Lollihits_Fruhlings Spass! (2005) 45 OGG 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Nordkraft OST (2005) 94 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Play House Vol. 8 (2CD 2005) 186 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS RTL2 Pres. Party Power Charts Vol.1 (2CD 2005) 163 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Essential R&B Spring 2005 (2CD 2005) 158 VBR 839 VARIOUS ARTISTS Remixland 2005 (2CD 2005) 205 CBR 839 VARIOUS ARTISTS RTL2 Praesentiert X-Trance Vol.1 (2CD 2005) 189 VBR 839 VARIOUS ARTISTS Trance 2005 Vol. 2 (2CD 2005) 159 VBR 839 HAGGARD Eppur Si Muove (2004) 46 CBR 838 MOONSORROW Kivenkantaja (2003) 74 CBR 838 OST John Ottman - Hide And Seek (2005) 23 OGG 838 TEMNOJAR Echo of Hyperborea (2003) 29 CBR 838 THE BRAVERY The Bravery (2005) 45 VBR 838 THRUDVANGAR Ahnenthron (2004) 62 VBR 838 VARIOUS ARTISTS 70's-80's Dance Collection (2005) 49 OGG 838 VARIOUS ARTISTS Future Trance Vol. -

Rhythms of Relation: Black Popular Music and Mobile Technologies

Rhythms of Relation: Black Popular Music and Mobile Technologies Alexander G. Weheliye In this essay I focus on the singular performances of the interface between (black) subjectivity and informational technologies in popular music, ask- ing how these performances impact current definitions of the technologi- cal. After a brief examination of those aspects of mobile technologies that gesture beyond disembodied communication, I turn to the multifarious manifestations of techno-informational gadgets (especially cellular/mobile telephones) in contemporary R&B, a genre that is acutely concerned, both in content and form, with the conjuring of interiority, emotion, and affect. The genre’s emphasis on these aspects provides an occasion to analyze how technology thoroughly permeates spheres that are thought to represent the hallmarks of humanist hallucinations of humanity. I outline the extensive and intensive interdependence of contemporary (black) popular music and mobile technologies in order to ascertain how these sonic formations refract communication and embodiment and ask how this impacts rul- ing definitions of the technological. The first group of musical examples surveyed consists of recordings released between 1999 and 2001; the sec- ond set are recordings from years 2009–2010. Since ten years is almost an eternity in the constantly changing universes of popular music and mobile technologies, analyzing the sonic archives from two different historical moments allows me to stress the general co-dependence of mobiles and music without silencing the breaks that separate these “epochs.” Finally, I gloss a visual example that stages overlooked dimensions of mobile tech- nologies so as to amplify the rhythmic flow between the scopic and the sonic.