Machete Cut Marks on Bone: Our Current Knowledge Base

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Condors and Bottom, the Combat Machete

NEW IMPORTS Top, the Hog Sticker Machete The Condors and bottom, the Combat Machete. Either blade would make a very useful light-duty trail knife for maintaining paths through heavy HAVE LANDED! vegetation. Left to right, the Condor Pipe Knife Dagger, Condor This new line from Central America combines Multi-Knife and Condor Jungle Bowie. The Jungle the best jungle designs with modern materials. Bowie was my pick of the three for all-round B Y S te V E N D I C K usefulness. While practically every Central and South American country has its own machete industry, there are a small number of brands that seem to be universally popular south of the Rio Grande. Tramontina from Brazil, Colima from Guatemala, and Imacasa from El Salvador are three of the big names. WI particularly remember one trip to Costa Rica when I asked some of the locals about the Larsson machetes made in that country. I was quickly told that they considered the Imacasa products far superior to their own local brand. Finding Imacasa knives and machetes has been kind of a hit and miss proposition in the U.S. I have the impression that the big hardware distrib- utors tend to go with the low bidder each time they place a large machete order. As a result, you never know what brand you will find in the local retailer from month to month. In the case of Imacasa, that may be changing. A new company, Condor Tool and Knife, is now importing a wide variety of blades and tools from El Salvador. -

The Lawa River P.O

INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS JHM-12 BACK TO THE LAWA RIVER P.O. Box 206 Kalimantan Mr. Peter Bird Martin Samarinda, East Executive Director Indonesia Institute of Current World Affairs April 1988 4 West Wheelock Street Hanover, New Hampshire 03755 USA Dear Peter, Two days and a night aboard the Aspian Noor, slowly chugging up the Mahakam and Pahu Rivers last December were enough to get me excited about the wind and speed of myfirst ride on the Kalhold Utama Company's logging road. Racing over smooth-packed earth in the night, the logging truck seemed like transport from another world. The driver, a wiry chain-smoker from South Sulawesi (the island east of Borneo) relished driving this road at night, headlights flashing yellow, red, or green in the eyes of nocturnal creatures stunned by the sudden brightness. He got poetic, talking about the road flowing through the jungle like a river, and pointing out how the treetops' deep black silhouettes stood out against the brilliant edge of the Milky Way. In the hour-long rush whoosh from the company's Pahu River landing place to the main logging camp, 69 kilometers over rolling hills to the south, the road began to seem almost miraculous to me, powerful technology in the starlight. When returned to the area almost three months later, any magic the company road held for me evaporated under the intensity of a mid-afternoon sun. The road was no river, but a heat-reflecting equatorial desert cutting through the ramains of logged-over forest interspersed with swidden fields of ripe padi. -

Small Replacement Parts Case, Empty A.6144 Old Ballpoint Pen with Head for Classic 0.62

2008 Item No. Page Item No. Page 0.23 00 – 5.01 01 – 1 22 0.61 63 5.09 33 5.10 10 – 0.62 00 – 2 – 23 – 5.11 93 0.63 86 3 24a Blister 0.64 03 – 5.12 32 – 4 25 0.70 52 5.15 83 0.80 00 – 5.16 30 – 26 – 4 0.82 41 5.47 23 29 0.71 00 – 5.49 03 – 30a – 5 0.73 33 5.49 33 30b 0.83 53 – 6 – 5.51 00 – 32 – 0.90 93 7 5.80 03 34 1.34 05 – 9 – 6.11 03 – 36 – 1.77 75 11 6.67 00 37 1.78 04 – 6.71 11 – 38 – 11a 1.88 02 6.87 13 38a 1.90 10 – 7.60 30 – 41 – 13 1.99 00 7.73 50 43 Ecoline 7.71 13 – 43a – 2.21 02 – 14 7.74 33 43b 3.91 40 2.10 12 – 14a – 7.80 03 – 44 – 3.03 39 14c 7.90 35 44a CH-6438 Ibach-Schwyz Switzerland 8.09 04 – 46 – Phone +41 (0)41 81 81 211 4.02 62 – 16 – Fax +41 (0)41 81 81 511 8.21 16 47b 4.43 33 18b www.victorinox.com Promotional P1 [email protected] material A VICTORINOX - MultiTools High in the picturesque Swiss Alps, the fourth generation of the Elsener family continues the tradition of Multi Tools and quality cutlery started by Charles and Victoria Elsener in 1884. In 1891 they obtained the first contract to supply the Swiss Army with a sturdy «Soldier’s Knife». -

Rules and Options

Rules and Options The author has attempted to draw as much as possible from the guidelines provided in the 5th edition Players Handbooks and Dungeon Master's Guide. Statistics for weapons listed in the Dungeon Master's Guide were used to develop the damage scales used in this book. Interestingly, these scales correspond fairly well with the values listed in the d20 Modern books. Game masters should feel free to modify any of the statistics or optional rules in this book as necessary. It is important to remember that Dungeons and Dragons abstracts combat to a degree, and does so more than many other game systems, in the name of playability. For this reason, the subtle differences that exist between many firearms will often drop below what might be called a "horizon of granularity." In D&D, for example, two pistols that real world shooters could spend hours discussing, debating how a few extra ounces of weight or different barrel lengths might affect accuracy, or how different kinds of ammunition (soft-nosed, armor-piercing, etc.) might affect damage, may be, in game terms, almost identical. This is neither good nor bad; it is just the way Dungeons and Dragons handles such things. Who can use firearms? Firearms are assumed to be martial ranged weapons. Characters from worlds where firearms are common and who can use martial ranged weapons will be proficient in them. Anyone else will have to train to gain proficiency— the specifics are left to individual game masters. Optionally, the game master may also allow characters with individual weapon proficiencies to trade one proficiency for an equivalent one at the time of character creation (e.g., monks can trade shortswords for one specific martial melee weapon like a war scythe, rogues can trade hand crossbows for one kind of firearm like a Glock 17 pistol, etc.). -

Annual Report 2016

Collecting Exhibiting Learning Connecting Building Supporting Volunteering & Publishing & Interpreting & Collaborating & Conserving & Staffing 2016 Annual Report 4 21 10 2 Message from the Chair 3 Message from the Director and the President 4 Collecting 10 Exhibiting & Publishing 14 Learning & Interpreting 18 Connecting & Collaborating 22 Building & Conserving 26 Supporting 30 Volunteering & Staffing 34 Financial Statements 18 22 36 The Year in Numbers Cover: Kettle (detail), 1978, by Philip Guston (Bequest of Daniel W. Dietrich II, 2016-3-17) © The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy McKee Gallery, New York; this spread, clockwise from top left: Untitled, c. 1957, by Norman Lewis (Purchased with funds contributed by the Committee for Prints, Drawings, and Photographs, 2016-36-1); Keith and Kathy Sachs, 1988–91, by Howard Hodgkin (Promised gift of Keith L. and Katherine Sachs) © Howard Hodgkin; Colorscape (detail), 2016, designed by Kéré Architecture (Commissioned by the Philadelphia Museum of Art for The Architecture of Francis Kéré: Building for Community); rendering © Gehry Partners, LLP; Inside Out Photography by the Philadelphia Museum of Art Photography Studio A Message A Message from the from the Chair Director and the President The past year represented the continuing strength of the Museum’s leadership, The work that we undertook during the past year is unfolding with dramatic results. trustees, staff, volunteers, city officials, and our many valued partners. Together, we Tremendous energy has gone into preparations for the next phase of our facilities have worked towards the realization of our long-term vision for this institution and a master plan to renew, improve, and expand our main building, and we continue reimagining of what it can be for tomorrow’s visitors. -

Texas Knifemakers Supply 2016-2017 Catalog

ORDERING AND POLICY INFORMATION Technical Help Please call us if you have questions. Our sales team will be glad to answer questions on how HOW TO to use our products, our services, and answer any shipping questions you may have. You may CONTACT US also email us at [email protected]. If contacting us about an order, please have your 5 digit Order ID number handy to expedite your service. TELEPHONE 1-888-461-8632 Online Orders 713-461-8632 You are able to securely place your order 24 hours a day from our website: TexasKnife.com. We do not store your credit card information. We do not share your personal information with ONLINE any 3rd party. To create a free online account, visit our website and click “New Customer” www.TexasKnife.com under the log in area on the right side of the screen. Enter your name, shipping information, phone number, and email address. By having an account, you can keep track of your order [email protected] history, receive updates as your order is processed and shipped, and you can create notifica- IN STORE tions to receive an email when an out of stock item is replenished. 10649 Haddington Dr. #180 Houston, TX 77043 Shop Hours Our brick and mortar store is open six days per week, except major holidays. We are located at 10649 Haddington Dr. #180 Houston, TX 77043. Our hours are (all times Central time): FAX Monday - Thursday: 8am to 5pm 713-461-8221 Friday: 8am to 3pm Saturday: 9am to 12pm We are closed Sunday, and on Memorial Day, Labor Day, Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Day. -

Playing with Knives: the Socialization of Self-Initiated Learners 3 4 1 David F

Child Development, xxxx 2015, Volume 00, Number 0, Pages 1–13 1 2 Playing With Knives: The Socialization of Self-Initiated Learners 3 4 1 David F. Lancy 5 Utah State University 6 7 8 Since Margaret Mead’s field studies in the South Pacific a century ago, there has been the tacit understanding 9 that as culture varies, so too must the socialization of children to become competent culture users and bearers. 10 More recently, the work of anthropologists has been mined to find broader patterns that may be common to 11 childhood across a range of societies. One improbable commonality has been the tolerance, even encourage- 12 ment, of toddler behavior that is patently risky, such as playing with or attempting to use a sharp-edged tool. 13 This laissez faire approach to socialization follows from a reliance on children as “self-initiated learners.” In 14 this article, ethnographic literature that shows why children are encouraged to learn without prompting or 15 guidance and how that happens is reviewed. 16 17 18 19 Concepts like socialization, parental caretaking A fruitful source of clues to the parental eth- “ ” 20 styles, and pedagogy are often studied in anthro- notheory is the culture shock experienced by the “ ” 21 pology within a cultural models framework. The investigator. Accompanied by his spouse during his 22 framework is built on the assumption that societies research on childhood among the Dusun in North Dispatch: 31.12.15No. CE: of Priya pages: 13 PE: Karpagavalli 23 incorporate templates or models to guide members Borneo, Williams reports: 24 (Quinn, 2005) that include customary practices, 25 sanctions for following or not following those prac- We were faced daily with Dusun parents raising 26 tices, and an ethnotheory that organizes these ideas their children in ways that violated the basic “ 27 and provides an overarching perspective. -

The Cutting Edge of Knives

THE CUTTING EDGE OF KNIVES A Chef’s Guide to Finding the Perfect Kitchen Knife spine handle tip blade bolster rivets c utting edge heel of a knife handle tip butt blade tang FORGED vs STAMPED FORGED KNIVES are heated and pounded using a single piece of metal. Because STAMPED KNIVES are stamped out of metal; much like you’d imagine a license plate would be stamped theyANATOMY are typically crafted by an expert, they are typically more expensive, but are of higher quality. out of a sheet of metal. These types of knives are typically less expensive and the blade is thinner and lighter. KNIFEedges Plain/Straight Edge Granton/Hollow Serrated Most knives come with a plain The grooves in a granton This knife edge is perfect for cutting edge. This edge helps the knife edge knife help keep food through bread crust, cooked meats, cut cleanly through foods. from sticking to the blade. tomatoes & other soft foods. STRAIGHT GRANTON SERRATED Types of knives PARING KNIFE 9 Pairing 9 Pairing 9 Asian 9 Asian 9 Steak 9 Cheese STEAK KNIFE 9 Utility 9 Asian 9 Santoku Knife 9 Butcher 9 Utility 9 Carving Knife 9 Fillet 9 Cheese 9 Cleaver 9 Bread BUTCHER KNIFE 9 Chef’s Knife 9 Boning Knife 9 Santoku Knife 9 Carving Knife UTILITY KNIFE MEAT CHEESE KNIFE (INCLUDING FISH & POULTRY » PAIRING » CLEAVER » ASIAN » CHEF’S KNIFE FILLET KNIFE » UTILITY » BONING KNIFE » BUTCHER » SANTOKU KNIFE » FILLET CLEAVER PRODUCE CHEF’S KNIFE » PAIRING » CHEF’S KNIFE » ASIAN » SANTOKU KNIFE » UTILITY » CARVING KNIFE BONING KNIFE » CLEAVER CHEESE SANTOKU KNIFE » PAIRING » CHEESE » ASIAN » CHEF’S KNIFE UTILITY » BREAD KNIFE COOKED MEAT CARVING KNIFE » STEAK » FILLET » ASIAN » CARVING ASIAN KNIVES offer a type of metal and processing that BREAD is unmatched by other types of knives typically produced from » ASIAN » BREAD the European style of production. -

Machetes — Specification

DUS 162 DRAFT UGANDA STANDARD Second Edition 2017-05-dd Machetes — Specification Reference number DUS 162: 2017 © UNBS 2017 DUS 162: 2017 Compliance with this standard does not, of itself confer immunity from legal obligations A Uganda Standard does not purport to include all necessary provisions of a contract. Users are responsible for its correct application © UNBS 2017 All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and microfilm, without prior written permission from UNBS. Requests for permission to reproduce this document should be addressed to The Executive Director Uganda National Bureau of Standards P.O. Box 6329 Kampala Uganda Tel: +256 414 333 250/1/2/3 Fax: +256 414 286 123 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.unbs.go.ug ii © UNBS 2017 – All rights reserved DUS 162:2017 Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................................................ iv 1 Scope ...................................................................................................................................................... 1 2 Normative references ............................................................................................................................ 1 3 Terms and definitions .......................................................................................................................... -

Household and Professional Knives Directory 2019

MAKERS OF THE ORIGINAL SWISS ARMY KNIFE | ESTABLISHED 1884 Household and Professional Knives Directory 2019 INFORMATION VICTORINOX 1884 - 2017 MORE THAN 130 YEARS OF EXPERIENCE AND LIVED SWISS TRADITION The little red pocket knife, with Cross & Shield more than 130 years has allowed us to develop emblem on the handle is an instantly products that are not only extraordinary in recognizable symbol of our company. In a design and quality, but also in their ability unique way, it conveys excellence in Swiss to serve as reliable companions on life’s crafts manship, and also the impressive expertise adventures, both great and small. of more than 2,000 employees worldwide. Today, the full range of Victorinox knives is The principles by which we do business, are as comprised of over 1,200 models. The range relevant today as they were in 1897 when our is presented in two, separate catalogs: company founder, Karl Elsener, developed the «Swiss Army Knives» and «Household and «Original Swiss Army Knife»: functionality, Professional Knives». We are pleased to offer innovation, iconic design and uncompromising this streamlined assortment, with our best, and quality. Our commitment to these principles for perhaps future classics. Carl Elsener CEO Victorinox 3 8 17 21 30 33 36 SWISS STANDARD FIBROX WOOD SWIBO SWISS CLASSIC Paring Knives 17 Chef‘s Knives 21 Chef‘s Knives 30 Chef‘s Knives 33 MODERN Paring Knives 8 Household and Slicing Knives 24 Slicing and Slicing Knives 34 Walnut Wood 36 Household Knives 10 Kitchen Sets 19 Boning Knives 25 Boning Knives 32 Boning Knives 35 Kitchen Sets 14 Chef‘s Knives 20 Butcher‘s Knives 28 Forks and Spatulas 15 38 41 43 48 53 55 GRAND ALLROUNDER STORAGE KITCHEN SHARPENING SCISSORS MAÎTRE Cutting Boards 41 Cutlery Blocks 43 UTENSILS + SAFETY Household and Professional Scissors POM Chef‘s Cases 44 Kitchen Utensils Sharpening Steels and 38 55 Cutlery Roll Bags 47 48 Knife Sharpeners 53 SUSTAINABILITY Since decades, issues concerning environmental protection Steel processing and sustainability have been given high priority at Victorinox. -

Samura Knives Brochure 2020

Damascus 1 MO-V 2 Pro-S 3 Okinawa 4 Super5 5 CONTENTS Samura Damascus knives made from the 67 layers of highest quality modern industrial Japanese Damascus BN577 Slicing Knife 230 mm / 9’’ steel, are a perfect combination of the ancient art of metal processing and “high-tech”. Resulting a blade hardness of HRC - 61, incredible The ergonomic G-10 handle design offers sharpness and durability. Combined with a modern complete control of the cutting process composite G10 handle for perfect comfort and control BN578 Chef’s Knife 200 mm / 8’’ Steel anti-microbial bolster BN573 Paring Knife 90mm / 3.5’’ BN579 Grand Chef’s Knife 240mm / 9.4” BN574 Utility Knife 125mm / 5’’ BN580 Small Santoku 145mm / 5.7’’ The steel blade continues through the Straight slopes handle offering a full tang knife providing the ultimate in balance and quality. 67 layers of Damascus steel deliver strength, sharpness and functionality BN575 Utility Knife 150mm / 6’’ BN581 Santoku 180mm / 7’’ Angle of sharpening 16-18 degrees. European double-sided sharpening of the blade Convex sharpening BN576 Boning Knife 165mm / 6.5’’ BN582 Nakiri 167mm / 6.6” DAMASCUS 1 The MO-V series of single-layered steel knives BN583 Paring Knife 90mm / 3.5’’ with an advanced ergonomic handle – the perfect combination of Japanese AUS-8 steel with a blade hardness of HRC 58 and a G10 composite handle, BN584 Utility Knife 125mm / 5’’ impreccable quality, contemporary design, amazing value. Ergonomic G-10 fiberglass plastic handle provides full cut control BN585 Utility Knife 150mm / 6’’ Antimicrobial -

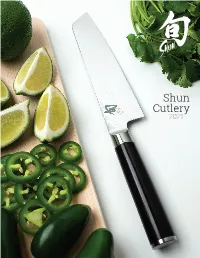

Shuncatalog 2021 Web.Pdf

Shun Cutlery 2021 Contents 2 New Products Handcrafted 4 Blade Shapes 12 Engetsu NEW! 6 Premium Materials tradition In Japan, the blade is more than a 10 Shun Anatomy tool; it’s a tradition. From legendary NEW! 14 Narukami samurai swords to the handcrafted culinary cutlery of today, the exquisite 11 Common Terms craftsmanship of Japanese blades is admired worldwide. 52 Shun Exclusives Since the 13th century, Seki City has been the heart of the Japanese NEW! 18 Premier Grey cutlery industry. For more than 112 53 Kai Housewares years, it has also been the home of Products Kai Corporation, the makers of Shun fi ne cutlery. Inspired by the traditions of ancient Japan, today’s highly 54 Block Sets skilled Shun artisans produce blades 22 Dual Core of unparalleled quality and beauty. Shun is dedicated to maintaining 58 Specialty Sets this ancient tradition by continuing to handcraft each knife in our Seki Hinoki City facilities. Each piece of this fi ne 60 kitchen cutlery takes at least 100 26 Premier Cutting Boards individual steps to complete. While we maintain these ancient 61 Steak Knives traditions of handcrafted quality, we also take advantage of thoroughly 62 Accessories modern, premium materials and 32 Classic Blonde state-of-the-art technology to provide Shun quality to millions of Quality Control professional chefs and avid home 66 cooks throughout the world. Our brand name comes from the 67 Use & Care Japanese culinary tradition of “shun.” 36 Classic Shun is a time—the exact moment 68 Honing & when a fruit is perfectly ripe, a Sharpening vegetable is at its best, or meat is at its most flavorful.