A DESIGN for LIFE a Personal Rumination on the Value of Rules

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Court Green: Dossier: Political Poetry Columbia College Chicago

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Court Green Publications 3-1-2007 Court Green: Dossier: Political Poetry Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/courtgreen Part of the Poetry Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Columbia College Chicago, "Court Green: Dossier: Political Poetry" (2007). Court Green. 4. https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/courtgreen/4 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Court Green by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. For more information, please contact [email protected]. court green 4 Court Green is published annually at Columbia College Chicago Court Green Editors: Arielle Greenberg, Tony Trigilio, and David Trinidad Managing Editor: Cora Jacobs Editorial Assistants: Ian Harris and Brandi Homan Court Green is published annually in association with the English Department of Columbia College Chicago. Our thanks to Ken Daley, Chair of the English Department; Dominic Pacyga, Interim Dean of Liberal Arts and Sciences; Steven Kapelke, Provost; and Dr. Warrick Carter, President of Columbia College Chicago. “The Late War”, from The Complete Poems of D.H. Lawrence by D.H. Lawrence, edited by V. de Sola Pinto & F. W. Roberts, copyright © 1964, 1971 by Angelo Ravagli and C. M. Weekley, Executors of the Estate of Frieda Lawrence Ravagli. Used by permission of Viking Penguin, a division of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. “In America” by Bernadette Mayer is reprinted from United Artists (No. -

Futureheads Announced As First Summer Ball Headliner | Nouse

Nouse Web Archives Futureheads announced as first Summer Ball headliner Page 1 of 3 News Comment MUSE. Politics Business Science Sport Roses Freshers Futureheads announced as first Summer Ball headliner By Harry Gallivan, Managing Director (2013/14) Wednesday 15 May 2013 The Futureheads YUSU have announced post-punk band The Futureheads as the first leading act for the 2013 Summer Ball at York Racecourse. Kallum Taylor, YUSU President, confirmed the act this afternoon. The Sunderland-born band has performed at prestigious venues such as Glastonbury in 2005 and the biggest open-air festival in Europe, Woodstock, with 300,000 people attending in 2009. Their latest 2012 album, Rant, marked a radical departure for the band. Featuring no musical instruments at all, it consisted entirely of a cappella covers, including covers of Black Eye Peas’ ‘Meet me Halfway’ and Kelis’ ‘Acapella’. In a 2011 interview, lead singer Barry Hyde said; “We were partly inspired by [80s a cappella group] The Flying Pickets. They were great singers but their tracks were a bit asexual sounding. We want this to be more rough.” The album was nominated for Artrocker’s ‘Album of the Year’ award in 2012, and was rated 8/10 by NME. In 2005, their cover of Kate Bush’s song, ‘Hounds of Love’, reached number 8 in the charts and was named best single by NME. The band has also accompanied The Foo Fighters and Snow Patrol during their stage sets. More announcements. including the biggest act of the night, will be announced in the coming weeks. The 2013 ball is expected to be an exciting event following on from last year’s headline acts, Feeder and Stooshe. -

The Futureheads, News and Tributes | Nouse

Nouse Web Archives The Futureheads, News and Tributes Page 1 of 2 News Comment MUSE. Politics Business Science Sport Roses Freshers Muse › Music › News Features Reviews Playlists The Futureheads, News and Tributes Thursday 4 May 2006 The difficult second album. So often a failure for many bands, but what of Sunderland’s finest? This offering takes a much darker tack than their self titled debut, echoing the punk rhythms and socially concious lyrics of The Clash and The Jam. They have also learned from the success of ‘Hounds of Love’, expanding on the successful backing harmonies throughout. Fans of the songs ‘A to B’ or ‘Hounds of Love’ may be disappointed here. Although ‘Favours for Favours’, ‘To the Sea’ and ‘Skip to the End’ are standout tracks, they don’t quite share the same anthemic resonance or catchiness. Several songs indicate a change in style without losing the distinctive Futureheads mark. This is most obvious in ‘Thursday’, which oddly echoes the intro to the Beach Boys’ classic ‘Wouldn’t it be Nice’. The bass driven ‘Burnt’ channels the Pixies’ loud/quiet sound in The Futureheads’ own unique way. Nonetheless, it doesn’t pulsate with raw passion in the same way as The Futureheads did and, although the new ideas are interesting, sometimes they fall short. The closing track ‘Face’ starts promisingly, ends abruptly and feels like an injustice, closing an unsatisfacory album in an unsatisfactory manner. Reviewed by Ben Toone Out 29/05/06 Most Read Discussed 1. Review: Little Mix – LM5 2. Led Astray – The Case Against Greta Van Fleet 3. -

An Interactive Video Installation for Young People

An interactive video installation for young people An arcade machine plays video messages from 2066 on to your palms. Join this playful, empowering mission to save the future. Place your hands into the arcade machine. A video message from 2066 plays on to your palms: “Sorry. We ruined the world.” Can you save the future? Uncover secret messages on an interactive mission that leads to the Multiverse Arcade – a headquarters of ideas within The Cowgate Centre. Explore a space full of young people’s thoughts on how to change the world. “What will you do when you’re in charge?” you are asked. Add your voice – the future is in your hands. This playful, empowering and thought-provoking event is created by Unfolding Theatre, New Writing North’s Young Writers’ City at Excelsior Academy and Queen’s Hall Youth Theatre. Venue Curriculum connections How to get involved The Cowgate Centre Houghton Avenue Multiverse Arcade inspires young We are looking for school and youth Newcastle upon Tyne people’s thinking about citizenship. It groups for us to visit before Multiverse NE5 3UT invites them to explore and talk about Arcade opens to the public. During Opening times the social and environmental issues a 2-hour creative workshop for young By appointment for school, youth and that they care about. It aims to inspire people, at your school or centre, we community groups and build young people’s confidence will create audio recordings that will be about the future roles they might take featured the piece. If you would like to Dates to influence change, through voting, take part, contact Morag Iles (contact 23–29 October 2019 volunteering and social action. -

A Full List of New Indie Albums 2019 Indie Is Not a Genre

indieisnotagenre.com A full list of new Indie Albums 2019 Indie is not a genre Date Artist Album Label 11 Jan Red Rum Club Matador Mom+Pop 11 Jan Friska Viljor Broken Crying Bob 11 Jan Minor Majority Napkin Poetry self-released 18 Jan De Staat Bubble Gum Caroline 18 Jan Steve Mason About The Light Domino 18 Jan Alice Merton Mint Modern Sky UK 18 Jan The Twilight Sad It Won't Be Like This All The Time Rock Action 18 Jan Sharon Van Etten Remind Me Tomorrow Jagjaguwar 25 Jan Balthazar Fever PIAS 25 Jan Blood Red Shoes Get Tragic Jazz Life 25 Jan Júníus Meyvant Across The Borders Record 25 Jan Keuning Prismism Pretty Faithful 25 Jan Mozes and the Firstborn Dadcore Burger 25 Jan Press Club Late Teens (UK Release) Hassle 25 Jan Sunflower Bean King of the Dudes Mom+Pop 1 indieisnotagenre.com 25 Jan The Yacht Club The Last Words That You Said To Me Beth Shalom Have Kept Me Here And Safe 25 Jan Toy Happy In The Hollow Tough Love 1 Feb Andy Burrows & Matt Reasons To Stay Alive Caroline Haig 1 Feb Calva Louise Rhinoceros Modern Sky UK 1 Feb Girlpool What Chaos Is Imaginary Anti- 1 Feb Highasakite Uranium Heart Propeller 1 Feb Joseph J. Jones Built On Broken Bones Vol. 2 Caroline 1 Feb Jungstötter Love Is PIAS 1 Feb Rustin Man Drift Code Domino 1 Feb Tiny Ruins Olympic Girls Marathon Artists / Milk 1 Feb White Lies Five PIAS 8 Feb Chain Wallet No Ritual Jansen 8 Feb Health Vol. -

“Into the Sensual World”: Gender Subversion in the Work of Kate Bush

“Into the Sensual World”: Gender Subversion in the Work of Kate Bush BA Thesis English Literature Supervisor: Dr U. Wilbers Semester 2 image: Sarah Neutkens, 2019 Severens 1 Engelse Taal en Cultuur Teacher who will receive this document: Dr Usha Wilbers Title of document: “Into the Sensual World”: Gender Subversion in the Work of Kate Bush Name of course: BA Thesis Course Date of submission: 14–06–2019 The work submitted here is the sole responsibility of the undersigned, who has neither committed plagiarism nor colluded in its production. Signed: Name of student: Student number: Severens 2 Abstract Kate Bush remains one of the most successful and original British female music artists and is often perceived as a female pioneer. This thesis analyses a selection of her earlier work in order to establish how she represents issues of gender and sexuality in her lyrics and performances. Her work is evaluated through the lens of two feminist theories: écriture feminine and gender performativity. Écriture féminine is employed to determine how Bush writes and reclaims female sexuality, while gender performativity subsequently shows how she transcends her position as a woman by taking on and representing characters of the opposite gender. This thesis argues that Bush constructs narratives in her lyrics to represent experiences which transcend the boundaries of binary gender and challenge social sexual norms. Keywords: Kate Bush, gender performativity, écriture féminine, song lyrics, popular music studies Severens 3 Table of Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 1. Theoretical Framework ................................................................................................... 8 2. Stepping Out Of The Page: Kate Bush Writing Women .............................................. 16 3. -

Artist Song Weird Al Yankovic My Own Eyes .38 Special Caught up in You .38 Special Hold on Loosely 3 Doors Down Here Without

Artist Song Weird Al Yankovic My Own Eyes .38 Special Caught Up in You .38 Special Hold On Loosely 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down When You're Young 30 Seconds to Mars Attack 30 Seconds to Mars Closer to the Edge 30 Seconds to Mars The Kill 30 Seconds to Mars Kings and Queens 30 Seconds to Mars This is War 311 Amber 311 Beautiful Disaster 311 Down 4 Non Blondes What's Up? 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect The 88 Sons and Daughters a-ha Take on Me Abnormality Visions AC/DC Back in Black (Live) AC/DC Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap (Live) AC/DC Fire Your Guns (Live) AC/DC For Those About to Rock (We Salute You) (Live) AC/DC Heatseeker (Live) AC/DC Hell Ain't a Bad Place to Be (Live) AC/DC Hells Bells (Live) AC/DC Highway to Hell (Live) AC/DC The Jack (Live) AC/DC Moneytalks (Live) AC/DC Shoot to Thrill (Live) AC/DC T.N.T. (Live) AC/DC Thunderstruck (Live) AC/DC Whole Lotta Rosie (Live) AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long (Live) Ace Frehley Outer Space Ace of Base The Sign The Acro-Brats Day Late, Dollar Short The Acro-Brats Hair Trigger Aerosmith Angel Aerosmith Back in the Saddle Aerosmith Crazy Aerosmith Cryin' Aerosmith Dream On (Live) Aerosmith Dude (Looks Like a Lady) Aerosmith Eat the Rich Aerosmith I Don't Want to Miss a Thing Aerosmith Janie's Got a Gun Aerosmith Legendary Child Aerosmith Livin' On the Edge Aerosmith Love in an Elevator Aerosmith Lover Alot Aerosmith Rag Doll Aerosmith Rats in the Cellar Aerosmith Seasons of Wither Aerosmith Sweet Emotion Aerosmith Toys in the Attic Aerosmith Train Kept A Rollin' Aerosmith Walk This Way AFI Beautiful Thieves AFI End Transmission AFI Girl's Not Grey AFI The Leaving Song, Pt. -

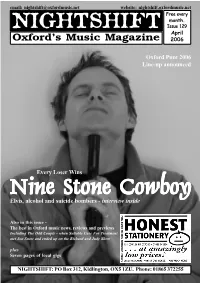

[email protected] Website: Nightshift.Oxfordmusic.Net Free Every Month

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 129 April Oxford’s Music Magazine 2006 Oxford Punt 2006 Line-up announced Every Loser Wins NineNineNine StoneStoneStone CoCoCowbowbowboyyy Elvis, alcohol and suicide bombers - interview inside Also in this issue - The best in Oxford music news, reviews and previews Including The Odd Couple - when Suitable Case For Treatment met Jon Snow and ended up on the Richard and Judy Show plus Seven pages of local gigs NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Harlette Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] PUNT LINE-UP ANNOUNCED The line-up for this year’s Oxford featured a sold-out show from Fell Punt has been finalised. The Punt, City Girl. now in its ninth year, is a one-night This years line up is: showcase of the best new unsigned BORDERS: Ally Craig and bands in Oxfordshire and takes Rebecca Mosley place on Wednesday 10th May. JONGLEURS: Witches, Xmas The event features nineteen acts Lights and The Keyboard Choir. across six venues in Oxford city THE PURPLE TURTLE: Mark and post-rock is featured across showcase of new musical talent in centre, starting at 6.15pm at Crozer, Dusty Sound System and what is one of the strongest Punt the county. In the meantime there Borders bookshop in Magdalen Where I’m Calling From. line-ups ever, showing the quality are a limited number of all-venue Street before heading off to THE CITY TAVERN: Shirley, of new music coming out of Oxford Punt Passes available, priced at £7, Jongleurs, The Purple Turtle, The Sow and The Joff Winks Band. -

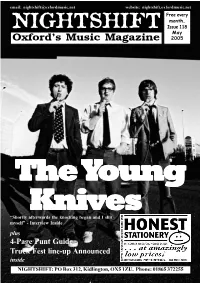

Issue 118.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 118 May Oxford’s Music Magazine 2005 TheTheThe YYYoungoungoung KniKniKnivvveseses “Shortly afterwards the knocking began and I shit myself” - Interview Inside plus 4-Page Punt Guide Truck Fest line-up Announced inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] THE OXFORD PUNT takes place this month, promising to be the definitive showcase of new unsigned local music talent. The Punt will feature 24 acts across eight venues in Oxford city centre on the night of Wednesday 11th May. In previous years the Punt has featured the very cream of Oxford’s unsigned bands and made the reputations of many bands who have played it, including Goldrush, Winnebago Deal, The Young Knives and Meanwhile, Back In Communist Russia. Inside this issue you will find a handy pull-out guide to the Punt which kicks off at Borders bookshop with acclaimed songstress Laima Bite and finishes six hours later at the Cellar with chaotic industrial noisemakers The Walk Off. There are still a handful of the 100 all-venue Punt Passes available as we went to press, on sale, priced £7 (plus booking fee) from oxfordmusic.net, Polar Bear Records or the Oxford Music Shop on St Aldates. Don’t miss out on the one of the best nights of live music you’ll BIFFY CLYRO AND THE MAGIC NUMBERS have been hear all year. confirmed as the headliners for this year’s Truck Festival. -

1 Unfolding Theatre the Making of PUTTING THE

Unfolding Theatre The Making of PUTTING THE BAND BACK TOGETHER (2016) This LMYE Laboratory sees a trio of interlocutors – Annie Rigby and Alex Elliott of Unfolding Theatre and their collaborator, musician Ross Millard of The Futureheads – grant insight into how they made their powerful and ambitious 2016 performance Putting the Band Back Together. The performance departs from a simple question, but one that has a weight in the biography of many: ‘Why did the band drift apart?’ Rigby details how this question, plucked from her own past, led her to embark onto a fascinating, deep and wide-reaching project, which conjugates communities across theatre- and music-making but which above all creates a larger community within and beyond the time and space in which the performance takes place. In this documentary, made up of clips from the show and memories of moments and encounters, Elliott, Rigby and Millard generously talk through the project’s initial sketches, crystallisation and realisation: from a desire to investigate this widespread nostalgia, to the choice of focusing on the story of mutual friend, theatre-maker Mark Lloyd and his wish to reform his old band having received a terminal cancer diagnosis, to the experience of getting into a room and jamming together. Our guests crucially focus on the piece’s afterlife: each performance forms a ‘house band’ in each location it visits on tour two hours before the show begins, and as Maddy Costa writes in her ‘zine collecting impressions from the house band: ‘Putting the Band Back Together is shaped by, energised by the invitation to take part’. -

Illp 3 L' 19 23 2 Beyond 143 /REPRISE 455228/WARNER BROS

SALES DATA COMPILED BY nielsen SoundScan TOP HE/XI-SEEKERS., Title ARTIST Title Released in ARTIST DISTRIBUTING LABEL (PRICE) TREE 8 NUMRER ' DISTRIBUTING LABEL (PRICE) LABEL &NUMBER / April. the set WAYMAN TISDALE CHARLOTTE SOMETIMES Waves & The Both Of Us Rebound was reissued last GEFFEN 011134/IGA (9.98) SAVING ABEL week with three THE FUTUREHEADS This Is Not The World Saving Abel NULL 01 (13.98) KIDOCO 060' 41 /12 98) additional LADYTRON A SKYLIT DRIVE Velocifero songs and musk WIRES And The Concept Of Breathing . ;, 98) TRAGIC HERO 036 /EAST WEST (14.98) MGMT videos, pushing THE VIRGINS The Virgins 4 Oracular Spectacular ATLANTIC 480572/AG (13.98) . COLUMBIA 19512' /SONY MUSIC (11 98) a 232% increase MJ FIVE FINGER DEATH PUNCH The Way Of The Fist for the album. Mi Sentimiento IRM 70116 (12.98) MACHETE 011151 (10.98) BON IVER SPIRITUALIZED Songs In A &E 31 22 16 For Emma, Forever Ago ;PACEMAN 542 /FONTANA INTERTATIONAL (12 98) JAGJAGUWAR 115" (14.98) 4 1 KIDZ IN THE HALL WE THE KINGS 32 17 The In Crowd WE the Kings MAJOR LEAGUE 2075 /DUCK DOWN (16 98) S -CURVE 52001 (8,98) 5 CUISILLOS PROZAK 33 29 Vive Y Dejame Vivir Tales From The Sick MUSART 5050/BALBOA (15.98) STRANGE 47 /RBC (18.98 CD /DVD) G' MATES OF STATE BRENDAN JAMES The Day Is Brave 34 13 3 Re- Arrange Us VELOUR 010825/DECCA (13.98) BARSUK 74 (13 98) THE COOL KIDS CHRIS SLIGH Running Back To You 30 3 The Bake Sale 35 34 5 6,A K.E. -

The Creative Power of a Question

“What if?” - The creative power of a question Transcript of the speech given by Darren Henley, Chief Executive of Arts Council England, at the National Glass Centre in Sunderland on 21st September 2016. Thank you for coming today, and thank you to our friends at the University of Sunderland and the National Glass Centre for hosting us. It’s been a tumultuous few months, which has left us with plenty to reflect on as a nation. So much of how we think of ourselves as a nation is shaped by our art and culture. And so, this seems like a good moment, and an important one, to think what that referendum result might mean for artists and arts organisations. I think it’s also fair to say that change, and the challenge that brings, also offers opportunities. And at this historic time, I think that events have thrown the focus on some cities, and Sunderland is one of them, that need to be thought about, and portrayed in a different light, to that which we've recently seen in the media. These cities, like Sunderland, Stoke, Hull or Coventry, may not be the first places that spring to mind when people talk about important cultural centres. But I've come to know them all well. And now, as the spotlight has been on them, I think it’s an opportune moment to highlight the extraordinary creative traditions of these cities and their people. And the way in which art and culture should work with these communities, to spark a revolution in how we think of, and use, our national creativity.