Sis U Line 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recent Publications in Music 2010

Fontes Artis Musicae, Vol. 57/4 (2010) RECENT PUBLICATIONS IN MUSIC R1 RECENT PUBLICATIONS IN MUSIC 2010 Compiled and edited by Geraldine E. Ostrove On behalf of the Pour le compte de Im Auftrag der International l'Association Internationale Internationalen Vereinigung Association of Music des Bibliothèques, Archives der Musikbibliotheken, Libraries Archives and et Centres de Musikarchive und Documentation Centres Documentation Musicaux Musikdokumentationszentren This list contains citations to literature about music in print and other media, emphasizing reference materials and works of research interest that appeared in 2009. It includes titles of new journals, but no journal articles or excerpts from compilations. Reporters who contribute regularly provide citations mainly or only from the year preceding the year this list is published in Fontes Artis Musicae. However, reporters may also submit retrospective lists cumulating publications from up to the previous five years. In the hope that geographic coverage of this list can be expanded, the compiler welcomes inquiries from bibliographers in countries not presently represented. CONTRIBUTORS Austria: Thomas Leibnitz New Zealand: Marilyn Portman Belgium: Johan Eeckeloo Nigeria: Santie De Jongh China, Hong Kong, Taiwan: Katie Lai Russia: Lyudmila Dedyukina Estonia: Katre Rissalu Senegal: Santie De Jongh Finland: Tuomas Tyyri South Africa: Santie De Jongh Germany: Susanne Hein Spain: José Ignacio Cano, Maria José Greece: Alexandros Charkiolakis González Ribot Hungary: Szepesi Zsuzsanna Tanzania: Santie De Jongh Iceland: Bryndis Vilbergsdóttir Turkey: Paul Alister Whitehead, Senem Ireland: Roy Stanley Acar Italy: Federica Biancheri United Kingdom: Rupert Ridgewell Japan: Sekine Toshiko United States: Karen Little, Liza Vick. The Netherlands: Joost van Gemert With thanks for assistance with translations and transcriptions to Kersti Blumenthal, Irina Kirchik, Everett Larsen and Thompson A. -

The Emergence of Estonian Hip-Hop in the 1990S Underlies Much Hip-Hop Sentiment” (2004: 152)

Th e Emergence of Estonian Hip-Hop in the 1990s Triin Vallaste Abstract In this article I trace the ways in which hip-hop as a global form of expression has become indigenized in post-Soviet Estonia. Hip-hop’s indigenization coincides with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. After the dissolution of the USSR, dominant Estonian social discourses eagerly celebrated re-entering the European-American world and embracing its values. The uncensored global media outlets acces- sible after 1991 and rapid developments in information technology shortly thereafter were crucial to the history of Estonian-language rap. Hip-hop artists’ extensive involvement with new media and technolo- gies refl ects an extremely swift transition from ill-equipped to fl uent manipulation of technology, which aff ected cultural production and structures of participation in various sociocultural spheres. While hip- hop culture emerged in the South Bronx during the early 1970s as a radical voice against increasing economic hardship and social marginalization, Estonian hip-hop was established in the early 1990s and developed in the context of a rapidly growing economy, rising living standards, and strong national feel- ing within a re-independent Estonian state. Hip-hop artists’ production vividly reveals both the legacies of Soviet rule and the particular political economy of post-Soviet Estonia. Hip-hop, with its roots in expressive Caribbean, (2003: 468). To invoke Tom Boellstorff ’s notion of African-American, and Latino cultures, has be- “dubbing culture” (Boellstorff 2003), indigenized come fundamental to millions of peoples’ iden- rap “is more than just a quotation: it adds a step, tities worldwide, a fact which necessitates mak- fi rst alienating something but then reworking it ing sense of the specifi c ways hip-hop functions in a new context” (2003: 237, cited in Keeler 2009: in diverse communities and cultures. -

Estonian-Art.Pdf

2_2014 1 News 3 The percentage act Raul Järg, Maria-Kristiina Soomre, Mari Emmus, Merike Estna, Ülle Luisk 6 I am a painting / Can't go on Discussion by Eha Komissarov, Maria-Kristiina Soomre, Marten Esko and Liina Siib 10 Long circuits for the pre-internet brain A correspondence between Niekolaas Johannes Lekkerkerk and Katja Novitskova 13 Post-internet art in the time of e-residency in Estonia Rebeka Põldsam 14 Platform: Experimenta! Tomaž Zupancˇicˇ 18 Total bass. Raul Keller’s exhibition What You Hear Is What You Get (Mostly) at EKKM Andrus Laansalu 21 Wild biscuits Jana Kukaine 24 Estonian Academy of Arts 100 Leonhard Lapin Insert: An education Laura Põld 27 When ambitions turned into caution Carl-Dag Lige 29 Picture in a museum. Nikolai Triik – symbol of hybrid Estonian modernism Tiina Abel 32 Notes from the capital of Estonian street art Aare Pilv 35 Not art, but the art of life Joonas Vangonen 38 From Balfron Tower to Crisis Point Aet Ader 41 Natural sciences and information technology in the service of art: the Rode altarpiece in close-up project Hilkka Hiiop and Hedi Kard 44 An Estonian designer without black bread? Kaarin Kivirähk 47 Rundum artist-run space and its elusive form Hanna Laura Kaljo, Mari-Leen Kiipli, Mari Volens, Kristina Õllek, Aap Tepper, Kulla Laas 50 Exhibitions 52 New books Estonian Art is included All issues of Estonian Art are also available on the Internet: http://www.estinst.ee/eng/estonian-art-eng/ in Art and Architecture Complete (EBSCO). Front cover: Kriss Soonik. Designer lingerie. -

Jumpin Issue 4.Indd

The Quakes OWDY FELLOWS. Sorry, this issue took us longer than expected, but look, it was worth the wait. More than forty pages of rock’n’roll, psychobilly, hillbilly, honky tonk, rockabilly and blues (and more...). First we’ve talked with Paul Roman, singer and guitar player for The Quakes. This interview was scheduled for a stick to your guns Hprevious issue and had to be delayed. On December 2nd, The uakesQ issued their newest output so we thought it was the right time for the interview. Earlier this year I discovered a very talented by fred Turgis singer and songwriter on a compilation album : Marcel Riesco founder of Truly Lover Trio. Once I heard the full album I knew I wanted him for Jumpin’. So here’s the interview with this young he Quakes are one of the first (if not and gifted guy. Cari Lee recently proved she was at ease with both hillbilly and rhythm’n’blues. the first) american psychobilly band. Like their compatriot the Stray Cats She tells us everything about this two kinds of music and her bands The Contenders and The Tthey crossed the sea to find fame in Saddle-Ites. Peter Sandmark aka Slim Sandy played many styles with many bands. The release of Europe where by the time the psychobilly scene was growing bigger and bigger. Roy his solo album “This Is Slim Sandy” gave us the occasion to make him talk about Ray Condo, The williams and nervous record quickly signed Crazy Rhythm Daddies and how to play drums, guitar and harmonica in the same time. -

Hopeless Youth!

HOPELESS YOUTH! Editors Francisco Martínez and Pille Runnel Hopeless Youth! is a collection of studies exploring what it means to be young today. Young people increasingly create their own identities and solidarities through experiences rather than through political or kin affiliations. It is the youth with the greatest hunger of experiences and cosmopolitan referents. Youngsters are hopeless because do not expect help from anybody and demonstrate scepticism about the future. As shown, contemporary youth is characterised by interim responses and situational thinking, developing particular skills that do not exist in previous generations. Beware that these essays will certainly resonate in your morning, afternoon and late night. Estonian National Museum Veski 32 51014 Tartu Estonia HOPELESS YOUTH! Tartu 2015 Editors: © Estonian National Francisco Martínez, Museum Pille Runnel © (Editing) Francisco English language editors: Martínez, Pille Runnel Daniel Edward Allen, © Authors Marcus Denton Layout, copy-editing: Ivi Tammaru Printing house: Greif Ltd Design: Margus Tamm This book was published with the support of the Font: Estonian National Museum. Aestii – official new font family of the Estonian National Museum, designed by Mart Anderson Graffiti on cover: Edward von Lõngus Photo processing: Arp Karm Endorsements Hopeless Youth! makes clear that the writing, thinking and doing involved in punk and hip hop culture, flâneurism, dubstep and techno music scenes, skateboarding, dumpster diving and hitch- hiking, for example, are central to culture on a more-than-mar- ginal level. This collection of essays is bound to be a staple ref- erence for anyone working with groups and individuals defining places on their own terms. Bradley L. Garrett, University of Southampton 5 Hopeless Youth! Hopeless Youth! is a timely addition to a type of scholarship which is proactive, progressive and provocative. -

Sounds of the Singing Revolution: Alo Mattiisen, Popular Music, And

Lawrence University Lux Lawrence University Honors Projects 5-30-2018 Sounds of the Singing Revolution: Alo Mattiisen, Popular Music, and the Estonian Independence Movement, 1987-1991 Allison Brooks-Conrad Lawrence University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lux.lawrence.edu/luhp Part of the Musicology Commons © Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Recommended Citation Brooks-Conrad, Allison, "Sounds of the Singing Revolution: Alo Mattiisen, Popular Music, and the Estonian Independence Movement, 1987-1991" (2018). Lawrence University Honors Projects. 124. https://lux.lawrence.edu/luhp/124 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by Lux. It has been accepted for inclusion in Lawrence University Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Lux. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sounds of the Singing Revolution: Alo Mattiisen, Popular Music, and the Estonian Independence Movement, 1987-1991 Allison Brooks-Conrad April 30th, 2018 Musicology Advisor: Professor Erica Scheinberg Acknowledgements Special thanks to my mother for introducing me to Estonia and for sharing my passion for this fascinating Baltic state. Thank you to both of my parents for their advice, support, and interest in this project. Thank you to Professor Colette Brautigam for making the digital images of Mingem Üles Mägedele that I use in this paper. Thank you to Merike Katt, director of Jõgeva Music School in Jõgeva, Estonia, for graciously sharing her images of Alo Mattiisen with me and for her support of this project. Finally, thank you to my advisor, Professor Erica Scheinberg. I am so grateful to her for her willingness to take on the obscure topics that interest me and for supporting this project from the beginning. -

Punkarite Roll Eestis Ning Nende Suhted Ühiskonnaga 1985–1995

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at Tartu University Library Tartu Ülikool Humanitaarteaduste ja kunstide valdkond Ajaloo ja arheoloogia instituut Joonas Vangonen PUNKARITE ROLL EESTIS NING NENDE SUHTED ÜHISKONNAGA 1985–1995 Magistritöö Juhendaja: Dr. Olaf Mertelsmann Tartu 2017 Sisukord Sissejuhatus ................................................................................................................................ 4 Teema valiku põhjendus ......................................................................................................... 4 Magistritöö eesmärk ja uurimisküsimused ............................................................................. 4 Varasemad teemakäsitlused .................................................................................................... 5 Magistritöö erisus võrreldes bakalaureusetööga ..................................................................... 6 Magistritöö struktuur .............................................................................................................. 7 1. Magistritöös kasutatavad põhiterminid ............................................................................... 9 2. Uurimistöö metoodika ...................................................................................................... 13 2.1. Andmete kogumise protsess ...................................................................................... 14 2.2. Valimi koostamine .................................................................................................... -

Remains of the Soviet Past in Estonia Ii

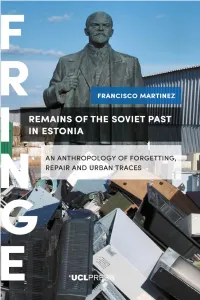

Remains of the Soviet Past in Estonia ii FRINGE Series Editors Alena Ledeneva and Peter Zusi, School of Slavonic and East European Studies, UCL The FRINGE series explores the roles that complexity, ambivalence and immeas- urability play in social and cultural phenomena. A cross-disciplinary initiative bringing together researchers from the humanities, social sciences and area stud- ies, the series examines how seemingly opposed notions such as centrality and marginality, clarity and ambiguity, can shift and converge when embedded in everyday practices. Alena Ledeneva is Professor of Politics and Society at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies of UCL. Peter Zusi is Lecturer at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies of UCL. By adopting the tropes of ‘repair’ and ‘waste’, this book innovatively manages to link various material registers from architecture, intergen- erational relations, affect and museums with ways of making the past pres- ent. Through a rigorous yet transdisciplinary method, Martínez brings together different scales and contexts that would often be segregated out. In this respect, the ethnography unfolds a deep and nuanced analysis, providing a useful comparative and insightful account of the processes of repair and waste making in all their material, social and ontological dimensions. Victor Buchli, Professor of Material Culture at UCL This book comprises an endearingly transdisciplinary ethnography of postsocialist material culture and social change in Estonia. Martínez creatively draws on a number of critical and cultural theorists, together with additional research on memory and political studies scholarship and the classics of anthropology. Grappling concurrently with time and space, the book offers a delightfully thick description of the material effects generated by the accelerated post-Soviet transformation in Estonia, inquiring into the generational specificities in experiencing and relating to the postsocialist condition through the conceptual anchors of wasted legacies and repair. -

Music,G En D E R & D Ifference

Kon 13 fe 20 re er M nz ob u ct O na s 2 en In i 1 Vi te c - s rs 0 t e , 1 r c A t G g io in n a m o l e r n a o n f m n r d e u p P s d o i c s d a t e n c l a o f i l r c e o i l n s d i s u & a l M p f e o r D s y t p i e s i r c f e t i v v f i e n e s U r e n c The conference is organised by: e The Institute for Music Sociology at the University of Music and Performing Arts In cooperation with: The Feminist Theory & Gender Studies Section of the Austrian Society of Sociology The Women & Gender Studies Section of the German Society of Sociology The Gender Studies Committee of the Swiss Society of Sociology BOOK OF ABSTRACTS Conference Music, Gender & Difference Intersectional and postcolonial perspectives on musical fields 10‐12 October 2013 University of Music and Performing Arts, Vienna CONTENTS Foreword 5 Reviewers 6 Venue information 7 Program overview 9 Detailed schedule 13 Abstracts (in alphabetical order) 23 FOREWORD Feminist research in recent decades has revealed the gender‐specific construction of the production, distribution, assessment, appropriation and experience of music, and has explored the participation and representation of women in various music genres. In addition, intersectional, queer and post‐ colonial approaches have shown how the construction of exoticism, the processes of “othering” and the production and circulation of difference has shaped musical fields in local and national contexts as well as on the global scale. -

(Post)Soviet/ (Post)Socialist Music, Theatre and Visual Arts

Gender and Sexualities in (post)Soviet/ (post)Socialist Music, Theatre and Visual Arts 19-20 April 2017 Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre and Graduate School of Culture Studies and Arts PROGRAM: Wednesday, 19 April EAMT, Room C105 10.30 Welcome coffee (on the 2nd floor) 11.00 Opening words 11.15-12.45 Stephen Amico How to Do Things with Theory: Queerness, Cultural Authority, and Post-Soviet Popular Music Moderator: Hannaliisa Uusma 12.45-14.00 LUNCH 14.00-15.30 Rebeka Põldsam Tulips and Carnations - Representations of post-Soviet Gender Subjectivities in Estonian Contemporary Art Moderator: Hannaliisa Uusma 15.30-16.00 COFFEE BREAK 16.00-17.30 Yngvar B. Steinholt 1. Invisible Unmissable: Russian Punk’s Mothers of Invention” (The role of women in Russian punk communities, based on fieldwork in 2009-11) Moderator: Brigitta Davidjants 2. “Painting the Void: Psychopathology in Ianka Diagileva’s Poetry” (Diagileva and her poem about depression) Moderator: Brigitta Davidjants 19.00 Documentary film evening in Artis cinema (Kino Artis) I Don't Believe in Anarchy (dir. Natalia Chumakova and Anna Tsyrlina, 2014) Introduction and discussion by Barbi Pilvre (Tallinn University) 1 Thursday, 20 April EAMT, Room A404 (Organ Hall) 09.30 Welcome coffee (on the 4th floor) 10.00-11.30 Tiina Pursiainen Rosenberg Is All Said and Done? Performing Genders on the Contemporary Stage Moderator: Rebeka Põldsam 11.30 -12.15 Harry Liivrand About Gaysensibility in post-Soviet Estonian Art, Especially in the 1990ies Moderator: Rebeka Põldsam 12.15-13.15 LUNCH 13.15-15.45 Presentations of doctoral students and young researchers: 1. -

Introduction ሖሗመ

INTRODUCTION ሖሗመ Me: What is so punk about you? Berndt: I say what I think! he concert was in one of the three main punk clubs in Halle; it was a TDIY (Do-It-Yourself; see below) event organized by people living in the same building in which the club is located. During the evening, two skin- head bands performed, drawing a big audience of punks and skins. Th e con- cert itself was a celebration of masculinity, typical of the tough street punk music style. Th e mosh pit mostly consisted of men, heavily tattooed and half-naked. Th e wild pogo also included hugging each other, a loud singa- long chorus and, at some point, even a fi ght. Th e musicians of the main band were older than the fi rst band and were in their forties. Th ey were dressed in typical skinhead style, with facial tattoos and heavy piercings. Most of their songs were narratives about their tough street life, being independent or ‘staying skinhead forever’. When the concert ended, the promoter of the club moved to the DJ booth and started to play ‘punk rock disco’. Most of the songs he played were of the Neue Deutsche Welle, German new wave music from the 1980s. Th e DJ chose mainly dark and existential tunes, experimen- tal electronic songs about alienation and unhappiness. Th e people danced with passion and I took my time to observe the crowd. Most of the people were in their twenties or thirties, representing the low-paid or unemployed ‘lower class’. -

A Home for 121 Nationalities Or Less

A Home for 121 Nationalities or Less: Nationalism, Ethnicity, and Integration in Post-Soviet Estonia DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Elo-Hanna Seljamaa Graduate Program in Comparative Studies The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Dorothy P. Noyes, Advisor Nicholas Breyfogle Ray Cashman Richard Herrmann Margaret Mills Copyright by Elo-Hanna Seljamaa 2012 Abstract When Estonia declared itself independent from the USSR in August 1991, it did so as the legal successor of the Republic of Estonia established in 1918, claiming to be returning to the Western world after a nearly five-decade rupture caused by illegal Soviet rule. Together with international recognition, this principle of legal continuity provided the new-old state with a starting point for vigorous, interlocking citizenship and property reforms that excluded Soviet-era settlers from the emerging body of citizens and naturalized Estonia’s dramatic transition to capitalism. As a precondition for membership in the European Union and NATO, Estonia launched in the late 1990s a national integration policy aimed at teaching mostly Russian-speaking Soviet-era settlers the Estonian language and reducing the number of people with undetermined citizenship. Twenty years into independence, Estonia is integrated into international organizations and takes pride in strong fiscal discipline, while income gaps continue to grow and nearly 7 per cent of the 1.36 million permanent residents are stateless; equally many have opted for Russian citizenship. Blending nationalist arguments with neoliberal ones, coalition parties are adamant about retaining the restorationist citizenship policy.