De 3457 0 13491 34572 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

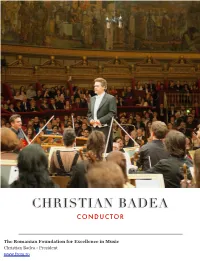

Christian Badea Conductor

CHRISTIAN BADEA CONDUCTOR The Romanian Foundation for Excellence in Music Christian Badea - President www.frem.ro Christian Badea has received exceptional acclaim throughout his career, which encompasses prestigious engagements in the foremost concert halls and opera houses of Europe, North America, Asia and Australia. Equally dividing his time between symphony and opera conducting, Christian Badea has appeared as a frequent guest in the major opera houses of the world. At the Metropolitan Opera in New York he conducted 167 performances in a wide variety of repertoire, including many of the MET international broadcasts. Among the opera houses where Christian Badea has guest conducted, are the Vienna State Opera, the Royal Opera House of Covent Garden in London, the Bayerische Staatsoper in München, the Staatsoper in Hamburg, the Deutsche Oper am Rhein in Düsseldorf, the Grand Théâtre de Genève, the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie in Brussels, the Netherlands Opera in Amsterdam, the Royal Opera theaters in Copenhagen and Stockholm, the Oslo Opera, the Teatro Regio in Torino and the Teatro 1 Christian Badea at the Metropolitan Opera - New York Comunale in Bologna, the Opera National de Lyon and in North America - the opera companies of Houston, Dallas, Toronto, Montreal and Detroit. In recent years, Christian Badea has received great acclaim for his work at the Budapest State Opera (Tannhäuser, Der fliegende Holländer and Parsifal) , the Sydney Opera with new productions of Tosca, La bohème, Die tote Stadt, Otello and Falstaff, Oslo Opera – a new production of Tannhäuser, collaborating with stage director Stefan Herheim and Goteborg Opera – a new Don Carlo and Turandot. -

In Santa Cruz This Summer for Special Summer Encore Productions

Contact: Peter Koht (831) 420-5154 [email protected] Release Date: Immediate “THE MET: LIVE IN HD” IN SANTA CRUZ THIS SUMMER FOR SPECIAL SUMMER ENCORE PRODUCTIONS New York and Centennial, Colo. – July 1, 2010 – The Metropolitan Opera and NCM Fathom present a series of four encore performances from the historic archives of the Peabody Award- winning The Met: Live in HD series in select movie theaters nationwide, including the Cinema 9 in Downtown Santa Cruz. Since 2006, NCM Fathom and The Metropolitan Opera have partnered to bring classic operatic performances to movie screens across America live with The Met: Live in HD series. The first Live in HD event was seen in 56 theaters in December 2006. Fathom has since expanded its participating theater footprint which now reaches more than 500 movie theaters in the United States. We’re thrilled to see these world class performances offered right here in downtown Santa Cruz,” said councilmember Cynthia Mathews. “We know there’s a dedicated base of local opera fans and a strong regional audience for these broadcasts. Now, thanks to contemporary technology and a creative partnership, the Metropolitan Opera performances will become a valuable addition to our already stellar lineup of visual and performing arts.” Tickets for The Met: Live in HD 2010 Summer Encores, shown in theaters on Wednesday evenings at 6:30 p.m. in all time zones and select Thursday matinees, are available at www.FathomEvents.com or by visiting the Regal Cinema’s box office. This summer’s series will feature: . Eugene Onegin – Wednesday, July 7 and Thursday, July 8– Soprano Renée Fleming and baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky star in Tchaikovsky’s lushly romantic masterpiece about mistimed love. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

The Met: Live in HD Returns to Theaters This Summer for Encore Screenings

April 19, 2012 The Met: Live in HD Returns to Theaters This Summer for Encore Screenings NCM Fathom Events and the Metropolitan Opera Bring Back Six Magnificent Operas Beginning June 13 NEW YORK & CENTENNIAL, Colo.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- The Metropolitan Opera and NCM Fathom Events team up once again to present six magnificent operas from the Emmy® and Peabody award-winning series, The Met: Live in HD. Fans of the popular series will enjoy select encore performances from the series, including Anna Bolena (June 13), Le Comte Ory (June 20), Don Giovanni (June 27), Les Contes d'Hoffmann (July 11), Lucia di Lammermoor (July 18), and Der Rosenkavalier (July 25) during Summer HD Encores. Tickets for The Met: Live in HD Summer 2012 Encores, shown in theaters Wednesday evenings at 6:30 p.m. in all time zones, are available at www.FathomEvents.com or at participating theater box offices. This will be the fourth series of Summer HD Encores, following a successful sixth season of The Met: Live in HD series and a presentation of Wagner's complete Ring Cycle this May. "Through the Summer Encores series, fans are able to catch great operas they may have missed during the regular season of the Met: Live in HD series, or simply see their favorites again," said Shelly Maxwell, executive vice president of NCM Fathom Events. The Met: Live in HD 2012 Summer Encores Schedule: Anna Bolena — Wednesday, June 13 Marco Armiliato conducts this David McVicar production which tells the story of an ill-fated queen (Anna Netrebko) driven insane by her unfaithful king. -

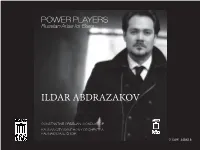

Ildar Abdrazakov Las Versiones Del Demonio

ENTREVISTA Ildar Abdrazakov Las versiones del demonio por Ingrid Haas ldar Abdrazakov es uno de los grandes bajos en la actualidad. A sus 39 años, goza ya de una carrera sólida y llena de éxitos en teatros tan importantes como la Scala de Milán, Iel Metropolitan Opera House de Nueva York, Washington Opera, Los Ángeles Ópera, Royal Opera House de Londres, Opéra Bastille de París, el Teatro Mariinsky, el Liceu de Barcelona, el Real de Madrid, la Ópera de Montecarlo, la Ópera de San Francisco, la Ópera Estatal de Viena y la Ópera Estatal de Baviera, entre otras. La voz de Abdrazakov ha conquistado a los públicos más exigentes y a directores de orquesta de la talla de Riccardo Muti, James Levine, Valery Gergiev, Gianandrea Noseda, Anthony Pappano, Riccardo Chailly y Bertrand de Billy, sólo por nombrar a algunos. “En las tres Con su cavernoso timbre, innegable musicalidad y gallarda versiones de presencia escénica, Abdrazakov ha cantado una amplia gama de Mefistófeles que he roles que van desde Fígaro en Le nozze di Figaro de Mozart, el rol cantado, mi Fausto titular y Leporello en Don Giovanni, Moïse en Moïse et Pharaon, ha sido siempre Assur en Semiramide, Don Basilio en Il Barbiere di Siviglia, las Ramón Vargas” tres de Rossini, Oroveso en Norma de Bellini, Méphistophélès Foto: Sergei Misenko en las versiones de Faust de Gounod y La damnation de Faust de Berlioz, el rol principal de Mefistofelede Boito, los Cuatro Sí, en efecto. Vine a cantar hace unos años a la Ciudad de México: Villanos de Les contes d’Hoffmann, Walter en Luisa Miller así un recital en la Sala Nezahualcóyotl y el Requiem de Verdi en como Oberto y Attila en las óperas homónimas de Verdi, Dosifei en Bellas Artes. -

MICHAEL FINNISSY at 70 the PIANO MUSIC (9) IAN PACE – Piano Recital at Deptford Town Hall, Goldsmith’S College, London

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2016). Michael Finnissy at 70: The piano music (9). This is the other version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17520/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] MICHAEL FINNISSY AT 70 THE PIANO MUSIC (9) IAN PACE – Piano Recital at Deptford Town Hall, Goldsmith’s College, London Thursday December 1st, 2016, 6:00 pm The event will begin with a discussion between Michael Finnissy and Ian Pace on the Verdi Transcriptions. MICHAEL FINNISSY Verdi Transcriptions Books 1-4 (1972-2005) 6:15 pm Books 1 and 2: Book 1 I. Aria: ‘Sciagurata! a questo lido ricercai l’amante infido!’, Oberto (Act 2) II. Trio: ‘Bella speranza in vero’, Un giorno di regno (Act 1) III. Chorus: ‘Il maledetto non ha fratelli’, Nabucco (Part 2) IV. -

Toscanini SSB Sib6

STAR SPANGLED MUSIC EDITIONS The Star-Spangled Banner for Orchestra (1943, revised 1951) Original Tune By JOHN STAFFORD SMITH Arranged and Orchestrated By ARTURO TOSCANINI Full Score Star Spangled Music Foundation www.starspangledmusic.org STAR SPANGLED MUSIC EDITIONS The Star-Spangled Banner for Orchestra (1943, revised 1951) Original Tune By JOHN STAFFORD SMITH Arranged and Orchestrated By ARTURO TOSCANINI 06/14/2014 Imprint Star Spangled Music Foundation www.starspangledmusic.org Star Spangled Music Editions Mark Clague, editor Performance materials available from the Star Spangled Music Foundation: www.starspangledmusic.org Published by the Star Spangled Music Foundation Musical arrangement © 1951 Estate of Arturo Toscanini, used by permission This edition © 2014 by the Star Spangled Music Foundation Ann Arbor, MI Printed in the U.S.A. Music Engraving: Michael-Thomas Foumai & Daniel Reed Editorial Assistance: Barbara Haws, Laura Jackson, Jacob Kimerer, and Gabe Smith COPYRIGHT NOTICE Toscanini’s arrangement of “The Star-Spangled Banner” is made in cooperation with the conductor’s heirs and the music remains copyrighted by the Estate of Arturo Toscanini ©1951. Prefatory texts and this edition are made available by the Star Spangled Music Foundation ©2014. SUPPORT STAR SPANGLED MUSIC EDITIONS This edition is offered free of charge for non-profit educational use and performance. Other permissions can be arranged through the Estate of Arturo Toscanini. We appreciate notice of your performances as it helps document our mission. Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Star Spangled Music Foundation to support this effort. The Star Spangled Music Foundation is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization. -

Elisa Citterio Discography 2009 Handel Between Heaven and Earth

Elisa Citterio Discography 2009 Handel Between Heaven And Earth CD Stefano Montanari, conductor Accademia Bizantina Soloists Sandrine Piau,Topi Lehtipuu 2008 Handel The Musick For The Royal Fireworks, Concerti A Due Cori CD Alfredo Bernardini Zefiro Fiorenza Concerti & Sonate CD Stefano Demicheli Dolce & Tempesta 2003 Various Storia Del Sonar A Quattro - Volume III CD Joseph Joachim Quartet 2001 Schuster 6 Quartetti Padovani CD Joseph Joachim Quartet 2000 Vivaldi La Tempesta di Mare CD Fabio Biondi Europa Galante 1998 Monteverdi Settimo Libro Dei Madrigali CD Claudio Cavina La Venexiana Recordings with L’orchestra del Teatro alla Scala di Milano 2015 Mozart Don Giovanni DVD Daniel Barenboim, conductor Orchestra & Chorus of Teatro alla Scala Peter Mattei, Bryn Terfel, Anna Netrebko, Barbara Frittoli, Giuseppe Filianoti, Anna Prohaska 2014 Jarre Notre-Dame De Paris DVD Paul Connelly, conductor Ballet Company & Orchestra of Teatro alla Scala Natalia Osipova, Roberto Bolle, Mick Zeni, Eris Nezha Wagner Goetterdammerung DVD Daniel Barenboim, conductor Orchestra & Chorus of Teatro alla Scala Maria Gortsevskaya, Lance Ryan, Iréne Theorin, Mikhail Petrenko Wagner Siegfried DVD Daniel Barenboim, conductor Orchestra & Chorus of Teatro alla Scala Lance Ryan, Peter Bronder, Terje Stensvold, Johannes Martin Kränzle, Alexander Tsymbalyuk, Anna Larsson, Nina Stemme, Rinnat Moriah Beethoven Fidelio VC Daniel Barenboim, conductor Orchestra & Chorus of Teatro alla Scala Peter Mattei, Falk Struckmann, Klaus Florian Vogt, Jonas Kaufmann, Anja Kampe, Kwangchul -

BAZZINI Complete Opera Transcriptions

95674 BAZZINI Complete Opera Transcriptions Anca Vasile Caraman violin · Alessandro Trebeschi piano Antonio Bazzini 1818-1897 CD1 65’09 CD4 61’30 CD5 53’40 Bellini 4. Fantaisie de Concert Mazzucato and Verdi Weber and Pacini Transcriptions et Paraphrases Op.17 (Il pirata) Op.27 15’08 1. Fantaisie sur plusieurs thêmes Transcriptions et Paraphrases Op.17 1. No.1 – Casta Diva (Norma) 7’59 de l’opéra de Mazzucato 1. No.5 – Act 2 Finale of 2. No.6 – Quartet CD3 58’41 (Esmeralda) Op.8 15’01 Oberon by Weber 7’20 from I Puritani 10’23 Donizetti 2. Fantasia (La traviata) Op.50 15’55 1. Fantaisie dramatique sur 3. Souvenir d’Attila 16’15 Tre fantasie sopra motivi della Saffo 3. Adagio, Variazione e Finale l’air final de 4. Fantasia su temi tratti da di Pacini sopra un tema di Bellini Lucia di Lammeroor Op.10 13’46 I Masnadieri 14’16 2. No.1 11’34 (I Capuleti e Montecchi) 16’30 3. No.2 14’59 4. Souvenir de Transcriptions et Paraphrases Op.17 4. No.3 19’43 Beatrice di Tenda Op.11 16’11 2. No.2 – Variations brillantes 5. Fantaisia Op.40 (La straniera) 14’02 sur plusieurs motifs (La figlia del reggimento) 9’44 CD2 65’16 3. No.3 – Scène et romance Bellini (Lucrezia Borgia) 11’05 Anca Vasile Caraman violin · Alessandro Trebeschi piano 1. Variations brillantes et Finale 4. No.4 – Fantaisie sur la romance (La sonnambula) Op.3 15’37 et un choeur (La favorita) 9’02 2. -

Ildar Abdrazakov

POWER PLAYERS Russian Arias for Bass ILDAR ABDRAZAKOV CONSTANTINE ORBELIAN, CONDUCTOR KAUNAS CITY SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA KAUNAS STATE CHOIR 1 0 13491 34562 8 ORIGINAL DELOS DE 3456 ILDAR ABDRAZAKOV • POWER PLAYERS DIGITAL iconic characters The dynamics of power in Russian opera and its most DE 3456 (707) 996-3844 • © 2013 Delos Productions, Inc., © 2013 Delos Productions, 95476-9998 CA Sonoma, 343, Box P.O. (800) 364-0645 [email protected] www.delosmusic.com CONSTANTINE ORBELIAN, CONDUCTOR ORBELIAN, CONSTANTINE ORCHESTRA CITY SYMPHONY KAUNAS CHOIR STATE KAUNAS Arias from: Arias Rachmaninov: Aleko the Tsar & Ludmila,Glinka: A Life for Ruslan Igor Borodin: Prince Boris GodunovMussorgsky: The Demon Rubinstein: Onegin, Iolanthe Eugene Tchaikovsky: Peace and War Prokofiev: Rimsky-Korsakov: Sadko 66:49 Time: Total Russian Arias for Bass ABDRAZAKOV ILDAR POWER PLAYERS ORIGINAL DELOS DE 3456 ILDAR ABDRAZAKOV • POWER PLAYERS DIGITAL POWER PLAYERS Russian Arias for Bass ILDAR ABDRAZAKOV 1. Sergei Rachmaninov: Aleko – “Ves tabor spit” (All the camp is asleep) (6:19) 2. Mikhail Glinka: Ruslan & Ludmila – “Farlaf’s Rondo” (3:34) 3. Glinka: Ruslan & Ludmila – “O pole, pole” (Oh, field, field) (11:47) 4. Alexander Borodin: Prince Igor – “Ne sna ne otdykha” (There’s no sleep, no repose) (7:38) 5. Modest Mussorgsky: Boris Godunov – “Kak vo gorode bylo vo Kazani” (At Kazan, where long ago I fought) (2:11) 6. Anton Rubinstein: The Demon – “Na Vozdushnom Okeane” (In the ocean of the sky) (5:05) 7. Piotr Tchaikovsky: Eugene Onegin – “Liubvi vsem vozrasty pokorny” (Love has nothing to do with age) (5:37) 8. Tchaikovsky: Iolanthe – “Gospod moi, yesli greshin ya” (Oh Lord, have pity on me!) (4:31) 9. -

Motezuma Por Alan Curtis Jóvenes Cuartetos Festivales De

REVISTA DE MÚSICA Año XXI - Nº 208 - Mayo 2006 - 6,30 € DOSIER Festivales de verano ENTREVISTAS Elisabeth Leonskaja Kaija Saariaho ACTUALIDAD Richard Goode Masaaki Suzuki Bernarda Fink Hervé Niquet DISCOS Nº 208 - Mayo 2006 SCHERZO Motezuma por Alan Curtis Jóvenes cuartetos AÑO XXI - Nº 208 - Mayo 2006 - 6,30 € 2 OPINIÓN Discos del mes 64 CON NOMBRE SCHERZO DISCOS PROPIO Sumario 65 6 Richard Goode Javier Alfaya DOSIER Festivales de verano 113 8 Giuliano Carmignola Enrique Martínez ENCUENTROS Kaija Saariaho 9 Bernarda Fink Bruno Serrou 142 Rafael Banús Irusta REPORTAJE 10 Hervé Niquet La fuente del canto moderno Pablo J.Vayón Arturo Reverter 146 11 Massaki Suzuki EDUCACIÓN Alfredo Brotons Muñoz Pedro Sarmiento 148 12 JAZZ AGENDA Pablo Sanz 150 18 ACTUALIDAD NACIONAL LIBROS 152 46 ACTUALIDAD INTERNACIONAL LA GUÍA 156 60 ENTREVISTA CONTRAPUNTO Elisabeth Leonskaja Norman Lebrecht 160 Juan Antonio Llorente Colaboran en este número: Javier Alfaya, Daniel Álvarez Vázquez, Julio Andrade Malde, Íñigo Arbiza, Rafael Banús Irusta, Emili Blasco, Alfredo Brotons Muñoz, José Antonio Cantón, Rodrigo Carrizo Couto, Rafael Díaz Gómez, Patrick Dillon, Pedro Eías Mamou, José Luis Fernández, Fernando Fraga, Joa- quín García, José Antonio García y García, Mario Gerteis, José Guerrero Martín, Fernando Herrero, Bernd Hoppe, Norman Lebrecht, Juan Antonio Llorente, Fiona Maddocks, Santiago Martín Bermúdez, Joaquín Martín de Sagarmínaga, Enrique Martínez Miura, Blas Matamoro, Erna Metdepenninghen, Pedro Mombiedro, Antonio Muñoz Molina, Miguel Ángel Nepomuceno, Rafael Ortega Basagoiti, Josep Pascual, Enrique Pérez Adrián, Javier Pérez Senz, Francisco Ramos, Arturo Reverter, Barbara Röder, Pablo Sanz, Pedro Sarmiento, Bruno Serrou, Franco Soda, Susan Stendec, José Luis Téllez, Asier Vallejo Ugarte, Claire Vaquero Williams, Pablo J. -

Constructing the Archive: an Annotated Catalogue of the Deon Van Der Walt

(De)constructing the archive: An annotated catalogue of the Deon van der Walt Collection in the NMMU Library Frederick Jacobus Buys January 2014 Submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Master of Music (Performing Arts) at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University Supervisor: Prof Zelda Potgieter TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DECLARATION i ABSTRACT ii OPSOMMING iii KEY WORDS iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION TO THIS STUDY 1 1. Aim of the research 1 2. Context & Rationale 2 3. Outlay of Chapters 4 CHAPTER 2 - (DE)CONSTRUCTING THE ARCHIVE: A BRIEF LITERATURE REVIEW 5 CHAPTER 3 - DEON VAN DER WALT: A LIFE CUT SHORT 9 CHAPTER 4 - THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION: AN ANNOTATED CATALOGUE 12 CHAPTER 5 - CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 18 1. The current state of the Deon van der Walt Collection 18 2. Suggestions and recommendations for the future of the Deon van der Walt Collection 21 SOURCES 24 APPENDIX A PERFORMANCE AND RECORDING LIST 29 APPEDIX B ANNOTED CATALOGUE OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION 41 APPENDIX C NELSON MANDELA METROPOLITAN UNIVERSTITY LIBRARY AND INFORMATION SERVICES (NMMU LIS) - CIRCULATION OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT (DVW) COLLECTION (DONATION) 280 APPENDIX D PAPER DELIVERED BY ZELDA POTGIETER AT THE OFFICIAL OPENING OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION, SOUTH CAMPUS LIBRARY, NMMU, ON 20 SEPTEMBER 2007 282 i DECLARATION I, Frederick Jacobus Buys (student no. 211267325), hereby declare that this treatise, in partial fulfilment for the degree M.Mus (Performing Arts), is my own work and that it has not previously been submitted for assessment or completion of any postgraduate qualification to another University or for another qualification.