Clothing and Gender Definition: . Joan Of·Arc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Enwau Prydeinig Gwyn

“Enwau Prydeinig gwyn?” ANGOR UNIVERSITY Wheeler, Sara Louise AlterNative: An international Journal of Indigenous Peoples DOI: 10.1177/1177180118786244 PRIFYSGOL BANGOR / B Published: 01/09/2018 Peer reviewed version Cyswllt i'r cyhoeddiad / Link to publication Dyfyniad o'r fersiwn a gyhoeddwyd / Citation for published version (APA): Wheeler, S. L. (2018). “Enwau Prydeinig gwyn?”: Problematizing the idea of “White British” names and naming practices from a Welsh perspective. AlterNative: An international Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 14(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180118786244 Hawliau Cyffredinol / General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. 26. Sep. 2021 “Enwau Prydeinig gwyn?” Problematizing the idea of “White British” names and naming practices from a Welsh perspective Abstract Our personal names are a potential source of information to those around us regarding several interconnected aspects of our lives, including our: ethnic, geographic, linguistic and cultural community of origin, and perhaps our national identity. -

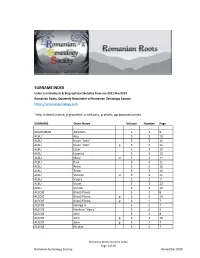

Surname Index

SURNAME INDEX Index to Individuals & Biographical Sketches from Jan 2012-Nov2019 Romanian Roots, Quarterly Newsletter of Romanian Genealogy Society https://romaniangenealogy.com *Key: d-death notice, g-gravesite, o-obituary, p-photo, pp-passport photo SURNAME Given Name Volume Number Page ACKERMAN Abraham 3 1 9 ALBU Ana 5 3 10 ALBU Iovan "John" 5 3 10 ALBU Iovan "John" p 5 3 11 ALBU Lazar 5 3 10 ALBU Lazarica 5 3 12 ALBU Mary d 5 3 11 ALBU Paul 5 3 11 ALBU Petra 5 3 10 ALBU Todor 5 3 10 ALBU Victoria d 5 3 11 ALBU Vioara 5 3 11 ALBU Viorel 5 3 12 ALBU Viorica 5 3 12 ALECXE (Iliesi) Florea 5 2 8 ALECXE (Iliesi) Florea p 5 2 10 ALECXE (Iliesi) Florea p 6 2 7 ALECXE George Jr. 6 2 7 ALECXE Haritron "Harry" 5 2 9 ALECXE John 5 2 8 ALECXE John p 5 2 10 ALECXE John p 6 2 7 ALECXE Nicolae 6 2 7 Romanian Roots Surname Index Page 1 of 16 Romanian Genealogy Society November 2020 SURNAME Given Name Volume Number Page ALECXE Nikita 5 2 8 ALECXE Thomas "Tom" 5 2 9 ALLER Joseph 6 3 8 ARON Dan p 1 4 10 AVRAM Dimitri 5 4 12 AVRAM Dimitri p 5 4 13 AVRAM (Szemrady) Frances 5 4 12 AVRAM George p 5 4 12 AVRAM Gheorghe "George" 5 4 11 AVRAM Gheorghe "George" p 5 4 11, 12 AVRAM Mara 5 4 13 AVRAM Petrin "Pedro" p 5 4 11 BACAINTAN (Cetean) Andronita "Anna" 8 3 9 BACAINTAN Anna 8 3 8 BACAINTAN Avram 8 3 8 BACAINTAN (Papas) Constance "Dina" 8 3 10 BACAINTAN John 8 3 8 BACAINTAN Juliana 8 3 9 BACAINTAN Mary 8 3 9 BACAINTAN Nicholas 8 3 9, 10 BACAINTAN Nicolae "Nick" 8 3 8, 9 BACAINTAN Saveta 8 3 9 BACAINTAN Silve 8 3 9 BAIAS Mihai 1 2 10 BALA Gligor "Gregory" 3 3 10 BALA Gligor "Gregory" 4 1 10 BALA Rose 3 3 10 BALOS Atanasie "Tom" p 1 3 11 BANDU Patru 5 3 12 BARBATEI (BARBETTY) Florence 6 4 11 BARBATEI (BARBETTY) Theodore 6 4 11 BARBOS Adam 6 4 4 BARBOS Marina 6 4 4 BARSAN Aurel Howard o 1 4 8 BARSAN Nicodim "Nick" 1 4 8 BARSAN Nicodim "Nick" p 1 4 10 BARSAN "Orefton" 1 4 9 BARSAN Seveta 1 4 9 BECHES (Valea) Anna 7 1 7 BECHES Elena Anna 7 1 8 BECHES Eli 7 1 7 BECHES Sr. -

Diplomatic List – Fall 2018

United States Department of State Diplomatic List Fall 2018 Preface This publication contains the names of the members of the diplomatic staffs of all bilateral missions and delegations (herein after “missions”) and their spouses. Members of the diplomatic staff are the members of the staff of the mission having diplomatic rank. These persons, with the exception of those identified by asterisks, enjoy full immunity under provisions of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations. Pertinent provisions of the Convention include the following: Article 29 The person of a diplomatic agent shall be inviolable. He shall not be liable to any form of arrest or detention. The receiving State shall treat him with due respect and shall take all appropriate steps to prevent any attack on his person, freedom, or dignity. Article 31 A diplomatic agent shall enjoy immunity from the criminal jurisdiction of the receiving State. He shall also enjoy immunity from its civil and administrative jurisdiction, except in the case of: (a) a real action relating to private immovable property situated in the territory of the receiving State, unless he holds it on behalf of the sending State for the purposes of the mission; (b) an action relating to succession in which the diplomatic agent is involved as an executor, administrator, heir or legatee as a private person and not on behalf of the sending State; (c) an action relating to any professional or commercial activity exercised by the diplomatic agent in the receiving State outside of his official functions. -- A diplomatic agent’s family members are entitled to the same immunities unless they are United States Nationals. -

New Romanian Publications on the Church History of Central Europe and Byzantium

364 Scrinium VΙI–VIII.2 (2011–2012). Ars Christiana NEW ROMANIAN PUBLICATIONS ON THE CHURCH HISTORY OF CENTRAL EUROPE AND BYZANTIUM The Romanian Academy has recently published two important edited volumes dedicated to the mediaeval history of Central Europe and Byzantium. Both of them contain articles which deal directly with Church history. 1. Christian Gastgeber, Ioan-Aurel Pop, Oliver Jens Schmitt, Alexandru Simon (eds.), Worlds in Change: Church Union and Crusading in the Fourteenth and Fi eenth Centuries (Cluj-Napoca: Romanian Academy. Center for Transylvanian Studies; IDC Press, 2009) (Transylvanian Review, vol. XVIII, supplement No. 2, 2009; Mélanges d’Histoire Générale, Nouvelle Série, IV/1) 444 p. ISSN 2067-1016, no ISBN. The following articles are directly related to Church history: Marie-Hélène Blanchet, Georges-Gennadios Scholarios et les Turcs. Une vision nuancée des conquérants (p. 101–116). The author traces the evolution in Scholarios’ thinking that brought him to a relatively favourable a itude toward the Turks. Michel Balivet, Un Fou en Christ au Concile de Florence : quelques remarques sur les ΜΟΝΟΧΙΤΩΝΕΣ chrétiens et musulmans au XVe siècle (p. 203–209). An episode relating to the Georgian bishop at the Council of Florence, who became a fool-in-Christ for three months, is considered within the frame of Byzantine and O oman sources on the impoverished dervishes in both Byzantium and Georgia. Iulian Mihai Damian, L’osservanza francescana e la ba aglia di Bel- grado (p. 211–237). The author examines the sources (both published and unpublished) representing Franciscan a itudes toward the po- litical and ecclesiastical realities in the epoch of the Ba le of Belgrad (1456), when Giovanni da Capestano, O.F.M., proclaimed a crusade against the Turks. -

Table 4: Full List of First Forenames Given, Scotland, 2016 (Final) in Alphabetical Order

Table 4: Full list of first forenames given, Scotland, 2016 (final) in alphabetical order NB: * indicates that, sadly, a baby who was given that first forename has since died Number of Number of Boys' names NB Girls' names NB babies babies A 1 A'lelia 1 A-Jay 1 Aadhya 2 Aadam 3 Aadrika 1 Aadarsh 1 Aadya 2 Aaden 2 Aafeen 1 Aadi 1 Aafreen 1 Aadit 1 Aaila 1 Aadrian 1 Aaima 2 Aadyanth 1 Aairah 1 Aaeryn 1 Aaisha 1 Aahad 1 Aaishah 1 Aahil 2 Aaiza 1 Aahyan 1 Aaleen 1 Aamir 1 Aaleyah 2 Aaran 2 Aalia 3 Aarav 5 Aaliah 1 Aaren 1 Aaliya 1 Aari 1 Aaliyah 34 Aarick 1 Aameera 1 Aariv 1 Aamina 1 Aariz 1 Aamira 1 Aarley-Ray 1 Aamirah 1 Aarlo 1 Aamna 1 Aaron 240 Aanya 2 Aaron-John 1 Aara 1 Aarran 1 Aaradhya 1 Aarron 1 Aaria 2 Aarvin 1 Aariah 3 Aaryan 1 Aariyah 1 Aaryav 2 Aarvi 1 Aaryn 2 Aarya 5 Aaryn-John 1 Aaryella 1 Aashutosh 1 Aashi 1 Aayan 8 Aashvi 1 Aayden 1 Aasiyah 2 Abaan 1 Aathira 1 Abaas 1 Aatiqa 1 Abdallah 2 Aayah 2 Abdelmadjid 1 Aayat 1 Abdijabar 1 Aayeshah 1 Abdul 6 Aayla 2 Abdul-Aziz 1 Aaylah 1 Abdul-Rafay 1 Abaigh 1 Abdul-Raheem 1 Abbey 15 Abdul-Rahman 2 Abbi 5 Abdul-Samee 1 Abbi-Leigh 1 Abdul-Wahhab 1 Abbie 83 * Abdulahad 1 Abbie-Leigh 2 Abdulaziz 1 Abbie-Rose 2 Abdulhaadi 2 Abbiegail 1 Abdullah 9 Abbigail 1 Abdullahi 1 Abby 28 Abdulmohsen 1 Abeeha 2 Abdulrahman 3 Abeera 2 Abdulsalam 1 Abena 1 Abdur-Rahman 2 Abi 14 Abdurahman 3 Abigail 96 Abdurraheem 1 Abigail-Lee 1 Abdurrahman 1 Abigaile 1 Abdussalam 1 Abiha 2 Abe 1 Abiola 2 © Crown Copyright 2017 Table 4 (continued) NB: * indicates that, sadly, a baby who was given that first forename has -

Workshop Papers: Monday – Thursday, November 17

Sunday, November 16 Workshops: MTAGS 2014: 7th Workshop on Many-Task Computing on Clouds, Grids, and Supercomputers TIME: 9AM – 5:30PM • ROOM: 295 ORGANIZERS: Ioan Raicu, Justin Wozniak, Ian Foster, Yong Zhao PDSW 2014: 9th Parallel Data Storage Workshop TIME: 9AM – 5:30PM • ROOM: 271/272 ORGANIZERS: Dean Hildebrand, Garth Gibson, Rob Ross, Joan Digney UltraVis ’14: The 9th Workshop on Ultrascale Visualization TIME: 9AM – 5:30PM • ROOM: 294 ORGANIZERS: Kwan-Liu Ma, Venkatram Vishwanath, Hongfeng Yu Second Workshop on Sustainable Software for Science: Practice and Experiences (WSSSPE 2) TIME: 9AM – 5:30PM • ROOM: 275-76-77 ORGANIZERS: Gabrielle D. Allen, Daniel S. Katz, Karen Cranston, Neil Chue Hong, Manish Parashar, David Proctor, Matthew Turk, Colin C. Venters, Nancy Wilkins-Diehr Workshop Papers: Workshop Title: The 5th International Workshop on Performance Modeling, Benchmarking and Simulation of High Performance Computer Systems (PMBS14) Paper: Energy-Performance Tradeoffs in Multilevel Checkpoint Strategies TIME: 9:00AM – 5:30PM • ROOM: 283-84-85 PRESENTERS: Prasanna Balaprakash, Leonardo Arturo Bautista Gomez, Mohamed-Slim Bouguerra, Stefan Wild, Franck Cappello, Paul Hovland Monday – Thursday, November 17-20 Booth: Globus Booth 3649 Monday, November 17 Tutorials: Advanced MPI Programming TIME: 8:30AM – 5PM • ROOM: 392 PRESENTERS: Pavan Balaji, William Gropp, Torsten Hoefler, Rajeev Thakur Parallel I/O in Practice TIME: 8:30AM – 5PM • ROOM: 386/387 PRESENTERS: Robert Latham, Robert Ross, Brent Welch, Katie Antypas Enhanced Campus Bridging via a Campus Data Service Using Globus and the Science DMZ TIME: 1:30PM – 5PM • ROOM: 394 PRESENTERS: Steve Tuecke, Vas Vasiliadis, Raj Kettimuthu Workshop Papers: Workshop Title: ExaMPI14: Exascale MPI 2014 Paper: Towards INT_MAX. -

VUID Last Name First Name Middle Name Suffix Received Date Precinct Voting Method 1000393069 AGUILLON GUADALUPE FRANK 8/2/2021 2

AUGUST 21 SPECIAL RUNOFF ELECTION | CUMULATIVE EV ROSTER | AUGUST 6, 2021 Received Voting VUID Last Name First Name Middle Name Suffix Precinct Date Method 1000393069 AGUILLON GUADALUPE FRANK 8/2/2021 25 By Mail 1000392999 AGUILLON MARY MARGARET 8/2/2021 25 By Mail 1000265476 AHRENDT FRED CLIFTON 8/4/2021 33 By Mail 1000351859 AIKMAN SHERRIE 8/4/2021 21 By Mail 1000266243 AIMONE NANCY VANCE 8/6/2021 33 By Mail 1000274770 AKINS TOMMY DALE 8/6/2021 33 By Mail 1000266329 ALLEN KATHY 8/5/2021 33 By Mail 1000339861 ALLEN KELVIN E 8/4/2021 33 In Person 1000396117 ALMENDAREZ MARTIN JR 8/5/2021 25 In Person 1005047865 ALVAREZ MARGARET DELAROSA 8/4/2021 33 By Mail 1004978480 ALVAREZ ROBERT 8/4/2021 33 By Mail 1150104083 ANDRUSS TIMOTHY AARON 8/4/2021 33 In Person 1070140681 ANGELL KERRY BOWEN 8/4/2021 25 By Mail 1070058188 ANGELL RICHARD ALTON 8/4/2021 25 By Mail 1000456248 ARAGE JIMMY 8/5/2021 33 By Mail 1000544074 ARNOT MARGUERITE LIGHT 8/4/2021 25 By Mail 1009439404 ASTOLFI GORDON ANDREW 8/4/2021 33 By Mail 2169821433 AUSTIN EDUVINA RAMOS 8/4/2021 33 By Mail 2157205686 AUSTIN ELOY RUBEN JR 8/4/2021 33 By Mail 1000461995 AZBILL EUGENE MORRIS JR 8/4/2021 33 By Mail 1000356491 BANDY NANCY BICKFORD 8/4/2021 21 By Mail 1000357022 BARKER JEANNE 8/6/2021 25 By Mail 1000385285 BARLETTA VINCENT JR 8/5/2021 21 By Mail 1172542025 BAUER JEANIE LOU 8/4/2021 33 In Person 1000456346 BAUKNIGHT VICKI FRANZ 8/6/2021 33 By Mail 1022664136 BAUKNIGHT JEFFREY JAMES 8/6/2021 33 In Person 1000273086 BAUKNIGHT JULIE C 8/5/2021 33 In Person 1000456333 BAUKNIGHT BRUCE -

Checklist with Images and Notes

1. The Annunciation Christoffel Van Sichem II (1580– 1658) Wood Engraving UWM Art Collection, Gift of Emile H. Mathis II Accession number 2012.002.0332 Notes: Signature cVs on rock. Measurements: Sheet 6 ¾ x 4 1/3; Image 4x 2 ¾. 2. The Annunciation Alessandro Vecchi Wood Engraving, printed 1617 UWM Art Collection, Gift of Emile H. Mathis II Accession number 2012.002.0352 Notes: Note on matting indicates date of 1617, Venice. Top inscription: La annuciatio de rpo. Bottom inscription: Ave Maria. Measurements: Sheet 5 7/8 x 4 1/8; Image 5 ¼ x 3 3/18. 3. The Annunciation From Small Passion Albrecht Durer (1471–1528) Woodcut UWM Art Collection, Gift of Emile H. Mathis II Accession number 2012.002.0009 Notes: Analagous piece in The Metropolitan Museum of Art (no date). See attached. Measurements: Sheet 5 ¼ x 4 1/8; Image 5 x 3 ¾. 4. The Annunciation Sir Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) Engraved by Theodore Galle Engraving UWM Art Collection, Gift of Emile H. Mathis II Accession number 2012.002.0320 Measurements: Sheet 12 x 7 7/8; Image 10 ¼ x 6 5/8. 5. The Annunciation After Maerten Van Heemskerck (1498–1574) Originally Printed by Harmen Jansz Muller c. 1566 UWM Art Collection, Gift of Emile H. Mathis II Accession number 2012.002.0188 Notes: Signature on bedpost “M. Haemskerck In.” monogram with overlapping letters “MVH Fec”. On lower right hand corner inscription “BEATI MUNDO CRODE, QUONIAM IPSI DEUM VIDEBUNT. 6” which is from the Beautitudes “Blessed are the pure in heart, they shall see God.” Matthew 5:8. -

International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes

International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes IOAN MICULA, VIOREL MICULA, S.C. EUROPEAN FOOD S.A., S.C. STARMILL S.R.L. AND S.C. MULTIPACK S.R.L. CLAIMANTS v. ROMANIA RESPONDENT ICSID Case No. ARB/05/20 ___________________________________________________________ AWARD ____________________________________________________________________________ Rendered by an Arbitral Tribunal composed of: Dr. Laurent Lévy, President Dr. Stanimir A. Alexandrov, Arbitrator Prof. Georges Abi-Saab, Arbitrator Secretary of the Tribunal Ms. Martina Polasek Assistant to the Tribunal Ms. Sabina Sacco Date of Dispatch to the Parties: 11 December 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 9 A. OVERVIEW OF THE DISPUTE .............................................................................................................. 9 B. THE PARTIES ................................................................................................................................... 9 1. The Claimants ......................................................................................................................................... 9 2. The Respondent.................................................................................................................................... 10 II. PROCEDURAL HISTORY .................................................................................................................. 11 A. INITIAL -

Names Meanings

Name Language/Cultural Origin Inherent Meaning Spiritual Connotation A Aaron, Aaran, Aaren, Aarin, Aaronn, Aarron, Aron, Arran, Arron Hebrew Light Bringer Radiating God's Light Abbot, Abbott Aramaic Spiritual Leader Walks In Truth Abdiel, Abdeel, Abdeil Hebrew Servant of God Worshiper Abdul, Abdoul Middle Eastern Servant Humble Abel, Abell Hebrew Breath Life of God Abi, Abbey, Abbi, Abby Anglo-Saxon God's Will Secure in God Abia, Abiah Hebrew God Is My Father Child of God Abiel, Abielle Hebrew Child of God Heir of the Kingdom Abigail, Abbigayle, Abbigail, Abbygayle, Abigael, Abigale Hebrew My Farther Rejoices Cherished of God Abijah, Abija, Abiya, Abiyah Hebrew Will of God Eternal Abner, Ab, Avner Hebrew Enlightener Believer of Truth Abraham, Abe, Abrahim, Abram Hebrew Father of Nations Founder Abriel, Abrielle French Innocent Tenderhearted Ace, Acey, Acie Latin Unity One With the Father Acton, Akton Old English Oak-Tree Settlement Agreeable Ada, Adah, Adalee, Aida Hebrew Ornament One Who Adorns Adael, Adayel Hebrew God Is Witness Vindicated Adalia, Adala, Adalin, Adelyn Hebrew Honor Courageous Adam, Addam, Adem Hebrew Formed of Earth In God's Image Adara, Adair, Adaira Hebrew Exalted Worthy of Praise Adaya, Adaiah Hebrew God's Jewel Valuable Addi, Addy Hebrew My Witness Chosen Addison, Adison, Adisson Old English Son of Adam In God's Image Adleaide, Addey, Addie Old German Joyful Spirit of Joy Adeline, Adalina, Adella, Adelle, Adelynn Old German Noble Under God's Guidance Adia, Adiah African Gift Gift of Glory Adiel, Addiel, Addielle -

Chapter 61 My Welsh Ancestors Going Back to the Middle Ages

Chapter 61 My Welsh Ancestors Going Back to the Middle Ages – Part 1 [originally written on 21 August 2020] Introduction I recently wrote about my 6th-great grandfather, John Owen, High Sheriff (1692- 1752), who was a Quaker and lived in Pennsylvania, just outside of Philadelphia. John’s father, Robert Owen (1657-1697), was born in Wales and immigrated to America in 1690. He left Wales since he was persecuted for practicing his Quaker faith. See: http://www.burksoakley.com/QuincyOakleyGenealogy/60- MyWelshQuakerAncestors.pdf In this narrative, I want to go back farther on John Owen’s ancestral lines and see if he has any interesting ancestors. Of course, his ancestors are also my ancestors. John Owen is part of the World Family Tree on Geni.com, and hopefully I’ll be able to go back many generations on one or more of his ancestral lines. John Owen’s Ancestors As I mentioned above, John Owen, High Sheriff, was my 6th-great grandfather: My line back to John Owen goes through my paternal grandmother, Kate Cameron Burks (1873-1954). Here is John Owen’s pedigree on Geni.com: Let me start by looking at Cadwaladr ap Maredudd (1556-1636), who was one of John Owen’s 2nd-great grandfathers. He appears in the red box in the chart shown above. Here is his pedigree on his mother’s side of the family (none of his father’s ancestors are known): One of Cadwaladr’s great-grandfathers was Sir Robert ap Rhys, Knight (1476- 1534) – see the red box in the chart above. -

Geographical Names As Cultural Heritage

NO. 48 MAY 2015 Preface Message from the Chairperson 3 From the Secretariat Message from the Secretariat 4 Geographical Names as Special Feature – Cultural Heritage Borgring- the battle over a name 5-6 Cultural Heritage International Symposium on Toponymy: 7-8 Geographical Names as Cultural Heritage The Cultural Heritage of geographical names 8-9 in the City of Petrópolis The valorization of the Tunisian cultural 10-15 heritage Geographical Name as Cultural Heritage 16 Preserving and promoting the historical- 17-19 cultural value …… From the Divisions Romano-Hellenic Division 20-22 Division francophone 22 Latin America Division 23 Norden Division 24 Portuguese-speaking Division 24 Africa South Division 24 From the Working Groups WG on Country Names 25 WG on Exonyms 25-26 WG on Toponymic Data Files and Gazetteers 27-28 WG on Evaluation and Implementation 29 WG on Publicity and Funding 29 Working Group on Cultural Heritage 30 From the Countries Ukraine 31-33 France 33-37 Egypt 37-38 Poland 39 Argentina 39-42 Mozambique 42-45 Tunisia 46-47 Republic of Korea 47 Lithuania 48-49 Indonesia 50-51 Viet Nam 52-55 Botswana 55 Special Projects and News Items The Third High Level Forum on GGIM and the 56-57 UN-GGIM-Africa Meeting Publications 58 In Memoriam: Dick Randall 1925-2015 59 Upcoming Meetings of Groups Associated 60 with Geographical Names UNGEGN Information Bulletin No. 48 May 2105 Page 1 NO. 48 MAY 2015 UNGEGN Information Bulletin The Information Bulletin of the United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names (formerly UNGEGN Newsletter) is issued twice a year by the Secretariat of the Group.