2018 Enwau Prydeinig Gwyn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Amazing Grace” Starring Ioan Gruffudd, Albert Finney, & Michael

“Amazing Grace” starring Ioan Gruffudd, Albert Finney, & Michael Gambon, 2006, PG, 118 minutes Major Themes: Slavery Freedom Perseverance & Faith Justice & Reform Politics Interesting info: Tagline – Every song has its story. Every generation has its hero. William Wilberforce (1759 – 1833) was a very gifted statesman, a social reformer, a philanthropist and an evangelical Christian. As well as working to bring about the end of the slave trade, and then to abolish slavery itself, he was concerned about mistreatment of animals (he was a founder member of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, later to become the RSPCA), education, the social impact of heavy gin drinking, and the need for missionaries in various parts of the world, including India and Africa (he was a founder of the Church Missionary Society and the British and Foreign Bible Society). Amazing Grace is the most honored and recorded song of all time. Amazon.com lists some 2000 currently available recordings of Amazing Grace. Nothing else comes remotely close. It crosses all lines—from classical to country, from rock to traditional folk. It is permanently ingrained in the culture. No other song has enjoyed such diverse rendering. He headed the parliamentary campaign against the British slave trade for 26 years until the passage of the Slave Trade Act 1807, when Parliament passed a bill to abolish the slave trade. (The film’s release is a way of marking the bicentennial of that event.) Some years later, just three days before Wilberforce’s death, slavery itself was completely abolished in Britain. Part of his epitaph in Westminster Abbey reads: In the prosecution of these objects he relied, not in vain, on God. -

Second Anniversary

What is a Critic? The Evil of Violence Conversation Cerith Mathias looks at the Gary Raymond explores the nature of Steph Power talks to Wales Window of Birmingham, arts criticism in a letter addressed to WNO’s David Alabama the future Pountney Wales Arts Review ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL Wales Arts Review - Anniversary Special 1 Wales Arts Contents Review Senior Editor Gary Raymond Managing Editor Phil Morris Design Editor Dean Lewis Fiction Editor John Lavin Music Editor Steph Power Non Fiction Up Front 3 A Letter Addressed to the Future: Editor What is a Critic? Ben Glover Gary Raymond Features 5 Against the Evil of Violence – The Wales Window of Alabama Cerith Mathias PDF Designer 8 An Interview with David Pountney, Artistic Ben Glover Director of WNO Steph Power 15 Epiphanies – On Joyce’s ‘The Dead’ John Lavin 20 Wales on Film: Zulu (1964) Phil Morris 22 Miles Beyond Glyndwr: What Does the Future Hold for Welsh Language Music? Elin Williams 24 Occupy Gezi: The Cultural Impact James Lloyd 28 The Thrill of it All: Glam! David Bowie Is… and the Curious Case of Adrian Street Craig Austin 31 Wales’ Past, Present and Future: A Land of Possibilities? Rhian E Jones 34 Jimmy Carter: Truth and Dare Ben Glover 36 Women and Parliament Jenny Willott MP 38 Cambriol Jon Gower 41 Postcards From The Basque Country: Imagined Communities Dylan Moore 43 Tennessee Williams: There’s No Success Like Failure Georgina Deverell 47 To the Detriment of Us All: The Untouched Legacy of Arthur Koestler and George Orwell Gary Raymond Wales Arts Review - Anniversary Special 2 by Gary Raymond In the final episode of Julian Barnes’ 1989 book, The History read to know we are not alone, as CS Lewis famously said, of the World in 10 ½ Chapters, titled ‘The Dream’, the then we write for similar reasons, and we write criticism protagonist finds himself in a Heaven, his every desire because it is the next step on from discursiveness; it is the catered for by a dedicated celestial personal assistant. -

LLAWENYDD YN LLANDYBIE Anrhydeddu Enillydd Tlws John a Ceridwen Hughes 2010

DATGANIAD I’R WASG DRAFFT Dydd Iau 3 Mehefin 2010 LLAWENYDD YN LLANDYBIE Anrhydeddu enillydd Tlws John a Ceridwen Hughes 2010 Heno, ar lwyfan pafiliwn Eisteddfod Genedlaethol Urdd Gobaith Cymru yng Ngheredigion, bydd Tlws John a Ceridwen Hughes Urdd Gobaith Cymru 2010 yn cael ei gyflwyno i Jennifer Maloney o Landybie. Dyfernir y tlws yn flynyddol i unigolion sydd wedi gwneud cyfraniad sylweddol i ieuenctid Cymru ac fe’i noddir gan Gerallt a Dewi Hughes yn enw eu diweddar rieni a oedd yn flaengar iawn ym maes datblygiad ieuenctid. Enwebwyd Jennifer Maloney gan aelodau a rhieni Adran Penrhyd a Chyngor Tref Rhydaman oedd yn awyddus i ddangos eu diolchgarwch am lafur diflino a brwdfrydedd Jennifer yn arwain yr Adran ers 34 o flynyddoedd. Ers ffurfio’r Adran nôl yn 1976, mae cannoedd o blant wedi elwa o ddoniau Jennifer ym maes dawnsio gwerin, canu, llefaru, clocsio ac wrth gymryd rhan mewn caneuon actol. Mae Jennifer ei hun wedi bod yn cystadlu yn yr Urdd ers yn chwech oed ac mae ganddi dros dri chant o gwpanau a degau o darianau a medalau yn ei chartref yn Llandybie. Roedd Jennifer yn awyddus i gychwyn yr Adran gan mai Saesneg oedd iaith ei chartref nôl yn 1976, ac roedd hi am i’w phlant hi a phlant eraill yr ardal gael y cyfle i gymdeithasu trwy gyfrwng y Gymraeg. Cafodd Jennifer wybod ei bod wedi ennill y Tlws mewn noson arbennig yn Rhydaman nôl ym mis Ebrill. Roedd dros 300 o bobl wedi dod yno i roi sypreis iddi. Meddai Jennifer: “Fe ges i gymaint o sioc pan ffeindies i mas mod i wedi ennill. -

James Strong Director

James Strong Director Agents Michelle Archer Assistant Grace Baxter [email protected] 020 3214 0991 Credits Television Production Company Notes CRIME Buccaneer/Britbox Lead Director and Executive Producer. 2021 Episodes 1-3. Writer: Irvine Welsh, based on his novel by the same name. Producer: David Blair. Executive producers: Irvine Welsh, Dean Cavanagh, Dougray Scott andTony Wood. VIGIL World Productions / BBC One Lead Director and Executive Producer. 2019 - 2020 Episodes 1- 3. Starring Suranne Jones, Rose Leslie, Shaun Evans. Writer: Tom Edge. Executive Producer: Simon Heath. United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes LIAR 2 Two Brothers/ ITV Lead Director and Executive Producer. 2019 Episodes 1-3. Writers: Jack and Harry Williams Producer: James Dean Executive Producer: Chris Aird Starring: Joanne Froggatt COUNCIL OF DADS NBC/ Jerry Bruckheimer Pilot Director and Executive Producer. 2019 Television/ Universal TV Inspired by the best-selling memoir of Bruce Feiler. Series ordered by NBC. Writers: Tony Phelan, Joan Rater. Producers: James Oh, Bruce Feiler. Exec Producers: Jerry Bruckheimer, Jonathan Littman, KristieAnne Read, Tony Phelan, Joan Rater. VANITY FAIR Mammoth/Amazon/ITV Lead Director and Executive Producer. 2017 - 2018 Episodes 1,2,3,4,5&7 Starring Olivia Cooke, Simon Russell Beale, Martin Clunes, Frances de la Tour, Suranne Jones. Writer: Gwyneth Hughes. Producer: Julia Stannard. Exec Producers: Gwyneth Hughes, Damien Timmer, Tom Mullens. LIAR ITV/Two Brothers Pictures Lead Director and Executive Producer. 2016 - 2017 Episodes 1 to 3. Writers: Harry and Jack Williams. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 88Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 88TH ACADEMY AWARDS ADULT BEGINNERS Actors: Nick Kroll. Bobby Cannavale. Matthew Paddock. Caleb Paddock. Joel McHale. Jason Mantzoukas. Mike Birbiglia. Bobby Moynihan. Actresses: Rose Byrne. Jane Krakowski. AFTER WORDS Actors: Óscar Jaenada. Actresses: Marcia Gay Harden. Jenna Ortega. THE AGE OF ADALINE Actors: Michiel Huisman. Harrison Ford. Actresses: Blake Lively. Kathy Baker. Ellen Burstyn. ALLELUIA Actors: Laurent Lucas. Actresses: Lola Dueñas. ALOFT Actors: Cillian Murphy. Zen McGrath. Winta McGrath. Peter McRobbie. Ian Tracey. William Shimell. Andy Murray. Actresses: Jennifer Connelly. Mélanie Laurent. Oona Chaplin. ALOHA Actors: Bradley Cooper. Bill Murray. John Krasinski. Danny McBride. Alec Baldwin. Bill Camp. Actresses: Emma Stone. Rachel McAdams. ALTERED MINDS Actors: Judd Hirsch. Ryan O'Nan. C. S. Lee. Joseph Lyle Taylor. Actresses: Caroline Lagerfelt. Jaime Ray Newman. ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS: THE ROAD CHIP Actors: Jason Lee. Tony Hale. Josh Green. Flula Borg. Eddie Steeples. Justin Long. Matthew Gray Gubler. Jesse McCartney. José D. Xuconoxtli, Jr.. Actresses: Kimberly Williams-Paisley. Bella Thorne. Uzo Aduba. Retta. Kaley Cuoco. Anna Faris. Christina Applegate. Jennifer Coolidge. Jesica Ahlberg. Denitra Isler. 88th Academy Awards Page 1 of 32 AMERICAN ULTRA Actors: Jesse Eisenberg. Topher Grace. Walton Goggins. John Leguizamo. Bill Pullman. Tony Hale. Actresses: Kristen Stewart. Connie Britton. AMY ANOMALISA Actors: Tom Noonan. David Thewlis. Actresses: Jennifer Jason Leigh. ANT-MAN Actors: Paul Rudd. Corey Stoll. Bobby Cannavale. Michael Peña. Tip "T.I." Harris. Anthony Mackie. Wood Harris. David Dastmalchian. Martin Donovan. Michael Douglas. Actresses: Evangeline Lilly. Judy Greer. Abby Ryder Fortson. Hayley Atwell. ARDOR Actors: Gael García Bernal. Claudio Tolcachir. -

UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Musicolinguistics: New Methodologies for Integrating Musical and Linguistic Data Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/59p4d43d Author Sleeper, Morgan Thomas Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Musicolinguistics: New Methodologies for Integrating Musical and Linguistic Data A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics by Morgan Thomas Sleeper Committee in charge: Professor Matthew Gordon, Chair Professor Eric Campbell Professor Timothy Cooley Professor Marianne Mithun June 2018 The dissertation of Morgan Thomas Sleeper is approved. ______________________________________________ Eric Campbell ______________________________________________ Timothy Cooley ______________________________________________ Marianne Mithun ______________________________________________ Matthew Gordon, Committee Chair June 2018 Musicolinguistics: New Methodologies for Integrating Musical and Linguistic Data Copyright © 2018 by Morgan Thomas Sleeper iii For Nina iv Acknowledgments This dissertation would not have been possible without the faculty, staff, and students of UCSB Linguistics, and I am so grateful to have gotten to know, learn from, and work with them during my time in Santa Barbara. I'd especially like to thank my dissertation committee, Matt Gordon, Marianne Mithun, Eric Campbell, and Tim Cooley. Their guidance, insight, and presence were instrumental in this work, but also throughout my entire graduate school experience: Matt for being the best advisor I could ask for; Marianne for all her support and positivity; Eric for his thoughtful comments and inspirational kindness; and Tim for making me feel so warmly welcome as a linguistics student in ethnomusicology. -

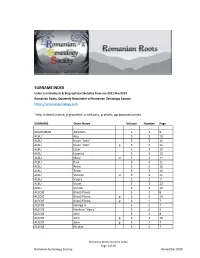

Surname Index

SURNAME INDEX Index to Individuals & Biographical Sketches from Jan 2012-Nov2019 Romanian Roots, Quarterly Newsletter of Romanian Genealogy Society https://romaniangenealogy.com *Key: d-death notice, g-gravesite, o-obituary, p-photo, pp-passport photo SURNAME Given Name Volume Number Page ACKERMAN Abraham 3 1 9 ALBU Ana 5 3 10 ALBU Iovan "John" 5 3 10 ALBU Iovan "John" p 5 3 11 ALBU Lazar 5 3 10 ALBU Lazarica 5 3 12 ALBU Mary d 5 3 11 ALBU Paul 5 3 11 ALBU Petra 5 3 10 ALBU Todor 5 3 10 ALBU Victoria d 5 3 11 ALBU Vioara 5 3 11 ALBU Viorel 5 3 12 ALBU Viorica 5 3 12 ALECXE (Iliesi) Florea 5 2 8 ALECXE (Iliesi) Florea p 5 2 10 ALECXE (Iliesi) Florea p 6 2 7 ALECXE George Jr. 6 2 7 ALECXE Haritron "Harry" 5 2 9 ALECXE John 5 2 8 ALECXE John p 5 2 10 ALECXE John p 6 2 7 ALECXE Nicolae 6 2 7 Romanian Roots Surname Index Page 1 of 16 Romanian Genealogy Society November 2020 SURNAME Given Name Volume Number Page ALECXE Nikita 5 2 8 ALECXE Thomas "Tom" 5 2 9 ALLER Joseph 6 3 8 ARON Dan p 1 4 10 AVRAM Dimitri 5 4 12 AVRAM Dimitri p 5 4 13 AVRAM (Szemrady) Frances 5 4 12 AVRAM George p 5 4 12 AVRAM Gheorghe "George" 5 4 11 AVRAM Gheorghe "George" p 5 4 11, 12 AVRAM Mara 5 4 13 AVRAM Petrin "Pedro" p 5 4 11 BACAINTAN (Cetean) Andronita "Anna" 8 3 9 BACAINTAN Anna 8 3 8 BACAINTAN Avram 8 3 8 BACAINTAN (Papas) Constance "Dina" 8 3 10 BACAINTAN John 8 3 8 BACAINTAN Juliana 8 3 9 BACAINTAN Mary 8 3 9 BACAINTAN Nicholas 8 3 9, 10 BACAINTAN Nicolae "Nick" 8 3 8, 9 BACAINTAN Saveta 8 3 9 BACAINTAN Silve 8 3 9 BAIAS Mihai 1 2 10 BALA Gligor "Gregory" 3 3 10 BALA Gligor "Gregory" 4 1 10 BALA Rose 3 3 10 BALOS Atanasie "Tom" p 1 3 11 BANDU Patru 5 3 12 BARBATEI (BARBETTY) Florence 6 4 11 BARBATEI (BARBETTY) Theodore 6 4 11 BARBOS Adam 6 4 4 BARBOS Marina 6 4 4 BARSAN Aurel Howard o 1 4 8 BARSAN Nicodim "Nick" 1 4 8 BARSAN Nicodim "Nick" p 1 4 10 BARSAN "Orefton" 1 4 9 BARSAN Seveta 1 4 9 BECHES (Valea) Anna 7 1 7 BECHES Elena Anna 7 1 8 BECHES Eli 7 1 7 BECHES Sr. -

Ioan Gruffudd

W51 & W52 17/12/16 - 30/12/16 Pages/Tudalennau: 2 A Welsh-Italian Christmas with Michela Chiappa 3 The Greatest Gift 4 Coming Home: Ioan Gruffudd 5 A Welsh-Italian Christmas with Michela Chiappa 6 Katherine Jenkins: Home For Christmas 7 Jonathan Meets… Joe Calzaghe 8 BBC National Orchestra and Chorus of Wales: Christmas Celebrations 9 Pobol y Cwm 10 Scrum V Live: Blues v Dragons 11 Wales on Top of the World 12 Wales Arts Review 2016 13 BBC National Orchestra and Chorus of Wales: Carols at Christmas 14 Pobol y Cwm Places of interest / Llefydd o ddiddordeb: Aberfan 12 Abertillery / Abertyleri 12 Aberystwyth 2 Bangor 2 Cardiff / Caerdydd 2, 3, 4 Llangennech 6 Manorbier / Maenorbŷr 3 Merthyr Tydfil / Merthyr Tudful 2 Newbridge / Trecelyn 7 Newport / Casnewydd 2, 3, 6 Swansea / Abertawe 6, 12 Follow @BBCWalesPress on Twitter to keep up with all the latest news from BBC Cymru Wales Dilynwch @BBCWalesPress ar Twitter i gael y newyddion diweddaraf am BBC Cymru Wales NOTE TO EDITORS: All details correct at time of going to press, but programmes are liable to change. Please check with BBC Cymru Wales Communications on 029 2032 2115 before publishing. NODYN I OLYGYDDION: Mae’r manylion hyn yn gywir wrth fynd i’r wasg, ond mae rhaglenni yn gallu newid. Cyn cyhoeddi gwybodaeth, cysylltwch â’r Adran Gyfathrebu ar 029 2032 2115. 1 A WELSH-ITALIAN CHRISTMAS WITH MICHELA CHIAPPA Monday, December 19 BBC One Wales, 7.30pm #WelshItalians A Welsh-Italian Christmas with Michela Chiappa is packed with culinary inspiration for the festive season. -

Mari Thomas Jewellery: Fitting New Home for Welsh Jewellery Brand

Mari Thomas Jewellery: fitting new home for Welsh jewellery brand Celebrated Welsh jeweller Mari Thomas was looking to leave her rented business premises when she spotted a local hotel up for sale and realised that it could make the perfect workshop and gallery. By her own admission, Mari Thomas is always moving the goalposts. “My dream when starting out 20 years ago was to have a small workshop and a cabinet of my work in a gallery in Swansea,” she says, “and that happened after about a year. So you set yourself another goal and when you start getting nearer to that you develop bigger and bigger dreams.” A few years ago, Mari sat down and sketched out a five-year plan for her business – “real blue-sky thinking, almost what the impossible could be,” she says. When she took another look at it again recently, she was amazed by how many milestones she had passed. One of the biggest moments in Mari’s career (and there have been many, including pieces made for Sting, actor Ioan Gruffudd, the National Eisteddfod festival and the Welsh Rugby Union), came this summer when she bought her own premises in Llandeilo. Elation, pure panic and a pat on the back With the rent on her previous building rising and plans to buy a new property having fallen through, Mari found her eye drawn to the Old Castle Hotel in the centre of town. “It was bigger than the place I’d been looking at and seemed an enormous hill to climb,” says Mari, who went on to secure a mortgage on the property from NatWest, with help from business development manager Mark Dobson, who was referred by Mark Davis from Stevenage-based brokerage firm Omega Commercial Solutions. -

Wales: the Heart of the Debate?

www.iwa.org.uk | Winter 2014/15 | No. 53 | £4.95 Wales: The heart of the debate? In the rush to appease Scottish and English public opinion will Wales’ voice be heard? + Gwyneth Lewis | Dai Smith | Helen Molyneux | Mark Drakeford | Rachel Trezise | Calvin Jones | Roger Scully | Gillian Clarke | Dylan Moore | The Institute of Welsh Affairs gratefully acknowledges funding support from the the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation and the Waterloo Foundation. The following organisations are corporate members: Public Sector Private Sector Voluntary Sector • Aberystwyth University • Acuity Legal • Age Cymru • BBC Cymru Wales • Arriva Trains Wales • Alcohol Concern Cymru • Cardiff County Council • Association of Chartered • Cartrefi Cymru • Cardiff School of Management Certified Accountants (ACCA) • Cartrefi Cymunedol • Cardiff University Library • Beaufort Research Ltd Community Housing Cymru • Centre for Regeneration • Blake Morgan • Citizens Advice Cymru Excellence Wales (CREW) • BT • Community - the union for life • Estyn • Cadarn Consulting Ltd • Cynon Taf Community Housing Group • Glandwr Cymru - The Canal & • Constructing Excellence in Wales • Disability Wales River Trust in Wales • Deryn • Eisteddfod Genedlaethol Cymru • Harvard College Library • Elan Valley Trust • Federation of Small Businesses Wales • Heritage Lottery Fund • Eversheds LLP • Friends of the Earth Cymru • Higher Education Wales • FBA • Gofal • Law Commission for England and Wales • Grayling • Institute Of Chartered Accountants • Literature Wales • Historix (R) Editions In England -

Newsletter Summer 2019 5

SUMMER 2019 St David’s Day Festival in Paris! 40 Year 9 pupils visited Disneyland Paris for the St. David’s Day Festival WWW.MARYIMMACULATE.ORG.UK MESSAGE FROM THE HEAD TEACHER With another year over, pupils and staff continue to thrive here We have some staff who are leaving us this year and some at Mary Immaculate High School. Year after year we have new staff joining us. In Maths, Mr Saunders is moving to received the coveted Green rating – meaning what we offer another school as well as Mr Hardee who is promoted to a youngsters is excellent and our standards – both academic and school in Barry. Our school science technician, Miss Marshall pastoral - are highly regarded. We continue to offer support to is also on her way to undertake a teaching qualification in many other schools, linked to our Green rating and we value England. those partnerships we have developed and continue to forge. Miss Major, our Food Technology teacher has taken early Our year 11 pupils have just finished their examinations – retirement this year and Mrs Davey one of the founding staff they have worked very hard with our teachers so members of our Bridge facility is also retiring. their outcomes can be as high as possible– we We of course welcome some new staff to the were once again able to provide a free school – Mrs Lawrence joins the Maths breakfast for all pupils prior to their exams, as department as Head of numeracy and Mr well as ongoing private home tuition for Perrett as our new Science Technician and Miss some pupils in English and Maths. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Culture, Welsh Language And

------------------------ Public Document Pack ------------------------ Agenda - Culture, Welsh Language and Communications Committee Meeting Venue: For further information contact: Committee Room 2 - Senedd Martha Da Gama Howells Meeting date: 30 January 2020 Committee Clerk Meeting time: 09.30 0300 200 6565 [email protected] ------ 1 Introductions, apologies, substitutions and declarations of interest 2 Inquiry into live music (9.30-10.30) (Pages 1 - 26) Betsan Moses, Chief Executive, National Eisteddfod of Wales Sioned Edwards, Deputy Artistic Director, National Eisteddfod of Wales Alun Llwyd, Chief Executive, PYST Neal Thompson, Co-founder, FOCUS Wales Break (10.30-10.40) 3 Inquiry into live music (10.40-11.40) Branwen Williams, Artist, Blodau Papur, Candelas and Siddi Osian Williams, Artist, Candelas Dilwyn Llwyd, Promoter, Neuadd Ogwen Marged Gwenllian, Artist, Y Cledrau 4 Paper(s) to note 4.1 Letter from Cymdeithas yr Iaith Gymraeg to the Minister for International Relations and the Welsh Language (Pages 27 - 28) 5 Private Debrief (11.40-12.00) By virtue of paragraph(s) vi of Standing Order 17.42 Agenda Item 2 Document is Restricted Pack Page 1 Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru / National Assembly for Wales Pwyllgor Diwylliant, y Gymraeg a Chyfathrebu / Culture, Welsh Language and Communications Committee Diwydiant Cerddoriaeth yng Nghymru / Music Industry in Wales CWLC M05 Ymateb gan PYST / Response from PYST 1. There are certainly not enough venues in communities across Wales to sustain music. This is often a reflection of wider economic problems, e.g. pubs closing down etc., but is primarily a reflection of the lack of promoters on the ground. 2. Through our work in distributing music digitally, our data show that there is a larger audience than ever before for Welsh music and Welsh-language music and that that audience discovers and listens to new music through streaming services.