Chapter-1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Introduction Term to Designate The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antrocom Journal of Anthropology ANTROCOM Journal Homepage

Antrocom Online Journal of Anthropology vol. 16. n. 1 (2020) 125-132 – ISSN 1973 – 2880 Antrocom Journal of Anthropology ANTROCOM journal homepage: http://www.antrocom.net Literacy Trends and Differences of Scheduled Tribes in West Bengal:A Community Level Analysis Sarnali Dutta1 and Samiran Bisai2 1Research Scholar, 2Associate Professor. Department of Anthropology & Tribal Studies, Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University, Purulia, West Bengal, India. Corresponding author: [email protected] keywords abstract Census data, India, Literacy, The present paper is based entirely on secondary sources of information, mainly drawn Tribal, West Bengal from the 2001 and 2011 Censuses of India and West Bengal. In this paper, an attempt has been made to analyse the present literacy trends of the ethnic communities of West Bengal, and comparing the data over a decade (2001 – 2011). The difference between male and female has also been focused. The fact remains that a large number of tribal women might have missed educational opportunities at different stages and in order to empower them varieties of skill training programmes have to be designed and organised. Implementation of systematic processes like Information Education Communication (IEC) should be done to educate communities. Introduction The term, tribe, comes from the word ‘tribus’ which in Latin is used to identify a group of persons forming a community and claiming descent from a common ancestor (Fried, 1975). Literacy is an important indicator of development among ethnic communities. According to Census, literacy is defined to be the ability to read and write a simple sentence in one’s own language understanding it; it is in this context that education has to be viewed from a modern perspective. -

District Disaster Management Plan 2020-21 Jalpaiguri

District Disaster Management Plan 2020-21 Jalpaiguri District Disaster Management Authority Jalpaiguri O/o the District Magistrate, Jalpaiguri West Bengal Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Aim and Objectives of the District Disaster Management Plan............................................ 1 1.2 Authority for the DDMP: DM Act 2005 ............................................................................... 2 1.3 Evolution of the DDMP ........................................................................................................ 3 1.4 Stakeholders and their responsibility .................................................................................... 4 1.5 How to use DDMP Framework ............................................................................................. 5 1.6 Approval Mechanism of the Plan: Authority for implementation (State Level/ District Level orders) ............................................................................................................................... 5 1.7 Plan Review & Updation: Periodicity ................................................................................... 6 2 Hazard, Vulnerability, Capacity and Risk Assessment ............................................................... 7 2.1 Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Assessment ......................................................................... 7 2.2 Matrix of Seasonality of Hazard .......................................................................................... -

New Regn.Pdf

LIST OF NEWLY REGISTERED DEALERS FOR THE PERIOD FROM 01-DECEMBER-08 TO 16-DECEMBER-08 CHARGE NAME VAT NO. CST NO. TRADE NAME ADDRESS ALIPUR 19604024078 19604024272 BAHAR COMMODEAL PVT. LTD. 16 BELVEDRE ROAD KOLKATA 700027 19604028055 MAHAVIR LOGISTICS 541/B, BLOCK 'N NW ALIPORE KOLKATA 700053 19604027085 P. S. ENTERPRISE 100 DIAMOND HARBOUR ROAD KOLKATA 700023 19604031062 19604031256 PULKIT HOLDINGS PVT. LTD. 16F JUDGES COURT ROAD KOLKATA 700027 19604030092 19604030286 R. S. INDUSTRIES (INDIA) 26E, TURF ROAD KALIGHAT 700025 19604026018 19604026212 RAJ LAXMI JEWELLERS 49/1 CIRCULAR GARDEN ROAD KOLKATA 700023 19604025048 19604025242 SAPNA HERBALS & COSMETICS PVT. LTD. 12/5 MOMINPUR ROAD KOLKATA 700023 19604029025 19604029219 SOOKERATING TEA ESTATE PVT. LTD. P-115, BLOCK-F NEW ALIPORE KOLKATA 700053 19604023011 SURFRAJ & CO. F-79 GARDENREACH ROAD KOLKATA 700024 ARMENIAN STREET 19521285018 19521285212 M/S. TEXPERTS INDIA PRIVATE LIMITED, 21, ROOPCHAND ROY STREET, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700007 19521286085 19521286279 TIRUPATI ENTERPRISES IST FLOOR, 153, RABINDRA SARANI, KOLKATA 700007 ASANSOL 19747189094 ARCHANA PEARLS 8, ELITE PLAZA G.C. MITRA ROAD ASANSOL 713301 19747194041 ASANSOL REFRIGERATOR MART 46 G.T. ROAD, DURGA MARKET, GIRIJA MOR ASANSOL 713301 19747182013 AUTO GARAGE FARI ROAD BARAKAR, ASANSOL 713324 19747178036 BADAL RUIDAS VIA- ASANSOL KALLA VILLAGE, RUIDAS PAR KALLA (C.H) 713340 19747175029 19747175223 BALBIR ENTERPRISES STATION ROAD BARAKAR 713324 19747179006 19747179297 BAZAR 24 24 G.T. ROAD (WEST) RANIGANJ SEARSOL RAJBARI 713358 -

The Most Lasting Impact of the Imperial Rule in the Jalpaiguri District

164 CHAPTER 111 THE BRITISH COLONIAL AUTHORITY AND ITS PENETRATION IN THE CAPITAL MARKET IN THE NORTHERN PART OF BENGAL The most lasting impact of the imperial rule in the Jalpaiguri District especially in the Western Dooars was the commercialisation of agriculture, and this process of commercialisation made an impact not only on the economy of West Bengal but also on society as well. J.A. Milligan during his settlement operations in the Jalpaiguri District in 1906-1916 was not im.pressed about the state of agriculture in the Jalpaiguri region. He ascribed the backward state of agriculture to the primitive mentality of the cultivators and the use of backdated agricultural implements by the cultivators. Despite this allegation he gave a list of cash crops which were grown in the Western Duars. He stated, "In places excellent tobacco is grown, notably in Falakata tehsil and in Patgram; mustard grown a good deal in the Duars; sugarcane in Baikunthapur and Boda to a small extent very little in the Duars". J.F. Grunning explained the reason behind the cultivation of varieties of crops in the region due to variation in rainfall in the Jalpaiguri district. He said "The annual rainfall varies greatly in different parts of the district ranging from 70 inches in Debiganj in the Boda Pargana to 130 inches at Jalpaiguri in the regulation part of the district, while in the Western Duars, close to the hills, it exceeds 200 inches per annum. In these circumstances it is not possible to treat the district as a whole and give one account of agriculture which will apply to all parts of it".^ Due to changes in the global market regarding consumer commodity structure suitable commercialisation at crops appeared to be profitable to colonial economy than continuation of traditional agricultural activities. -

Disaster Management Plan of Nagrakata Block

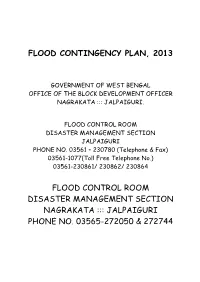

FLOOD CONTINGENCY PLAN, 2013 GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL OFFICE OF THE BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICER NAGRAKATA ::: JALPAIGURI. FLOOD CONTROL ROOM DISASTER MANAGEMENT SECTION JALPAIGURI PHONE NO. 03561 – 230780 (Telephone & Fax) 03561-1077(Toll Free Telephone No.) 03561-230861/ 230862/ 230864 FLOOD CONTROL ROOM DISASTER MANAGEMENT SECTION NAGRAKATA ::: JALPAIGURI PHONE NO. 03565-272050 & 272744 Introduction Block administration in general, and all three tier P.R. bodies in particular are giving the best of their activities to all round development of human habitats including living and material properties. As a part of developmental administrative wing, effort with a view to achieving target of materializing a really developed state of affairs in every sphere of our lives, are always exerted & ideas put forth by all concerned. However, much of our sincere endeavors in this direction are so often battered & hamstrung by sudden visit of ominous calamities and evil disasters. Thus, to combat such ruthless spells & minimize risk hazards and loss of resources, surroundings, our achievements, concrete preparation on Disaster Management is an inevitable part of our curriculum. Such preparedness of ours undoubtedly involves all departments, sectors concerned. Hence, we prepare a realistic Flood Contingency Plan to combat the ruthless damage caused to our flourishing habitats. Accordingly, this time for 2013, an elaborate plan has been worked out with every aspiration to successfully rise above the situation pursuing a planned step forward. BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICER NAGRAKATA ::: JALPAIGURI. CONTACT TELEPHONE NUMBERS FOR NAGRAKATA DEVELOPMENT BLOCK. SL. Name of the Office Telephone No. NO. 01. B.D.O, Nagrakata 03565-272050 Savapati, 02. Nagrakata Panchayat 03565-272309 Samity 03. -

Tribes in India

SIXTH SEMESTER (HONS) PAPER: DSE3T/ UNIT-I TRIBES IN INDIA Brief History: The tribal population is found in almost all parts of the world. India is one of the two largest concentrations of tribal population. The tribal community constitutes an important part of Indian social structure. Tribes are earliest communities as they are the first settlers. The tribal are said to be the original inhabitants of this land. These groups are still in primitive stage and often referred to as Primitive or Adavasis, Aborigines or Girijans and so on. The tribal population in India, according to 2011 census is 8.6%. At present India has the second largest population in the world next to Africa. Our most of the tribal population is concentrated in the eastern (West Bengal, Orissa, Bihar, Jharkhand) and central (Madhya Pradesh, Chhattishgarh, Andhra Pradesh) tribal belt. Among the major tribes, the population of Bhil is about six million followed by the Gond (about 5 million), the Santal (about 4 million), and the Oraon (about 2 million). Tribals are called variously in different countries. For instance, in the United States of America, they are known as ‘Red Indians’, in Australia as ‘Aborigines’, in the European countries as ‘Gypsys’ , in the African and Asian countries as ‘Tribals’. The term ‘tribes’ in the Indian context today are referred as ‘Scheduled Tribes’. These communities are regarded as the earliest among the present inhabitants of India. And it is considered that they have survived here with their unchanging ways of life for centuries. Many of the tribals are still in a primitive stage and far from the impact of modern civilization. -

George Van Driem Lectures Historical Relations Between Sikkim And

George van Driem lectures Historical relations between Sikkim and Nepal since the 17th century and their ethnolinguistic consequences and ramifications, lecture for students and team members of the project « Phonetics, Phonology and New Orthographies: Helping Native Language Communities in the Himalayas », Linguistics Institute, University of Bern, 31 March 2017. Who are the Japanese, and where do the Japanese come from?, invited lecture presented at the workshop ‘Human Evolution in Eurasia elucidated through Genetics, Archaeology and Linguistics’ hosted by the National Institute of Genetics at Mishima, 17 March 2017. Previously unknown episodes in the peopling of the greater Himalayan region, invited lecture at the International Consortium for East Himalayan Ethnolinguistic Prehistory, La Trobe University, Bundoora, 8 February 2017. Transitivity in Lohorung, invited keynote lecture at the Kiranti language workshop, Université Paris Diderot, 2 December 2016. The Denisovan Legacy in Tibet and Beyond, invited guest lecture at the 1st Tibetan Language Linguistic Forum, Nánkāi University, Tiānjīn, 27 August 2016. Some epistemic categories in the Dzongkha verb: The dangers of Platonic essentialism in linguistics and in life, invited guest lecture at the 1st Sino-Tibetan Language Research Methodology Workshop, Nánkāi University, Tiānjīn, 25 August 2016. Proto-Trans-Himalayan verbal morphology: Kiranti languages, the Gongduk and the Black Mountain Mönpa, invited guest lecture at the 1st Sino-Tibetan Language Research Methodology Workshop, Nánkāi University, Tiānjīn, 25 August 2016. Ethnolinguistic phylogeography and prehistory: The Eastern Himalayan region as a cradle of ethnogenesis and linguistic diversification in the prehistoric past, invited guest lecture at the 1st Sino-Tibetan Language Research Methodology Workshop, Nánkāi University, Tiānjīn, 24 August 2016. -

A Case Study of the Tea Plantation Industry in Himalayan and Sub - Himalayan Region of Bengal (1879 – 2000)

RISE AND FALL OF THE BENGALI ENTREPRENEURSHIP: A CASE STUDY OF THE TEA PLANTATION INDUSTRY IN HIMALAYAN AND SUB - HIMALAYAN REGION OF BENGAL (1879 – 2000) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY BY SUPAM BISWAS GUIDE Dr. SHYAMAL CH. GUHA ROY CO – GUIDE PROFESSOR ANANDA GOPAL GHOSH DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL 2015 JULY DECLARATION I declare that the thesis entitled RISE AND FALL OF THE BENGALI ENTREPRENEURSHIP: A CASE STUDY OF THE TEA PLANTATION INDUSTRY IN HIMALAYAN AND SUB - HIMALAYAN REGION OF BENGAL (1879 – 2000) has been prepared by me under the guidance of DR. Shyamal Ch. Guha Roy, Retired Associate Professor, Dept. of History, Siliguri College, Dist – Darjeeling and co – guidance of Retired Professor Ananda Gopal Ghosh , Dept. of History, University of North Bengal. No part of this thesis has formed the basis for the award of any degree or fellowship previously. Supam Biswas Department of History North Bengal University, Raja Rammuhanpur, Dist. Darjeeling, West Bengal. Date: 18.06.2015 Abstract Title Rise and Fall of The Bengali Entrepreneurship: A Case Study of The Tea Plantation Industry In Himalayan and Sub Himalayan Region of Bengal (1879 – 2000) The ownership and control of the tea planting and manufacturing companies in the Himalayan and sub – Himalayan region of Bengal were enjoyed by two communities, to wit the Europeans and the Indians especially the Bengalis migrated from various part of undivided Eastern and Southern Bengal. In the true sense the Europeans were the harbinger in this field. Assam by far the foremost region in tea production was closely followed by Bengal whose tea producing areas included the hill areas and the plains of the Terai in Darjeeling district, the Dooars in Jalpaiguri district and Chittagong. -

Chapter 2 STUDY AREA

Chapter 2 STUDY AREA . STUDY AREA An important inclusion in the National Parks family, Gorumara National Park (GNP) is famous for its prestigious inhabitant one-horned great Indian Rhino. This is one of the last few small pockets in Eastern India harboring natural population of Rhinoceros unicornis L., along with other mega and majestic herbivores like Indian Elephant, Gaur or Indian Bison and is covered with rich vegetation. GNP had been a wild land sanctuary (Vide notification no. 5181-FOR, date: 02.08.1949) and a reserved forest since 1895 (notification no. 3147- FOR, date: 2nd July, 1895 with corrections later on), under the Indian forest act (VII of 1878). Formerly, an area of 2129 acre was first declared as Gorumara Wild Life Sanctuary (GWLS) vide Gov. Notification no. 5181-For, date: 02.08.1949. Subsequently, the notification under the Wildlife (protection) act, 1972, [vide no. 5400- For, date: 24th June, 1976] covering a total area of 8.62 sq km declaring the area as GWLS. In 1994, with Govt. notification no. 319_ For, dated 31st January, 1994 was issued with the intention of declaring the area as GNP, with major extension of the existing GWLS and now it covered a total area of 79.99 sq km. On 21st November, 1995, following a reorganization of the forest directorate of West Bengal, the total area of the GNP, curved out of the Jalpaiguri forest division was handed over to the Wild Life Division – II under the Conservator of Forest, Wild Life Circle [vide GOV. of West Bengal notification no. 4983- For, date 25th September, 1995]. -

Human Interference and Avifaunal Diversity of Two Wetlands of Jalpaiguri, West Bengal, India

JoTT COMMUNI C ATION 3(12): 2253–2262 Human interference and avifaunal diversity of two wetlands of Jalpaiguri, West Bengal, India Tanmay Datta Department of Zoology, Ananda Chandra College, Jalpaiguri, West Bengal 735101, India Email: [email protected] Date of publication (online): 26 December 2011 Abstract: Avifaunal diversity and abundance were studied in two wetlands of Jalpaiguri Date of publication (print): 26 December 2011 District, West Bengal, India, in relation to eight wetland characteristics supposedly ISSN 0974-7907 (online) | 0974-7893 (print) directly or indirectly affected by human activities. Although the climatic and geophysical conditions of both the wetlands are almost similar, a total of 80 bird species were recorded Editor: Rajiv S. Kalsi from one wetland and the other supported only 42 species. The relationship between Manuscript details: habitat characteristics and community structure varied throughout the year, suggesting Ms # o2739 that the birds respond differently to one or other habitat characteristic depending on Received 28 March 2011 the season. Larger wetland size supported higher bird diversity and abundance as far Final received 18 October 2011 as resident and local migrants are concerned. Winter migrant density and diversity, Finally accepted 28 October 2011 however, reached higher values in structurally more heterogeneous wetlands having fewer submerged aquatic vegetation. All these habitat characteristics become highly Citation: Datta, T. (2011). Human interference and avifaunal diversity of two wetlands of Jalpaig- influenced by intense agricultural practices in the wetland with fewer bird diversity and uri, West Bengal, India. Journal of Threatened density. Taxa 3(12): 2253–2262. Keywords: Habitat heterogeneity, human interference, Jalpaiguri, submerged aquatic Copyright: © Tanmay Datta 2011. -

Tribal Women in the Democratic Political Process a Study of Tribal Women in the Dooars and Terai Regions of North Bengal

TRIBAL WOMEN IN THE DEMOCRATIC POLITICAL PROCESS A STUDY OF TRIBAL WOMEN IN THE DOOARS AND TERAI REGIONS OF NORTH BENGAL A Thesis submitted to the University of North Bengal For the Award of Doctor of Philosophy In Department of Political Science By Renuca Rajni Beck Supervisor Professor Manas Chakrabarty Department of Political Science University of North Bengal August, 2018 Dedicated To My Son Srinjoy (Kutush) ABSTRACT Active participation in the democratic bodies (like the local self-government) and the democratic political processes of the marginalized section of society like the tribal women can help their empowerment and integration into the socio-political order and reduces the scope for social unrest. The present study is about the nature of political participation of tribal women in the democratic political processes in two distinctive areas of North Bengal, in the Dooars of Jalpaiguri district (where economy is based on tea plantation) and the Terai of Darjeeling district (with agriculture-based economy). The study would explore the political social and economic changes that political participation can bring about in the life of the tribal women and tribal communities in the tea gardens and in the agriculture-based economy. The region known as North Bengal consists of six northern districts of West Bengal, namely, Darjeeling, Jalpaiguri, Malda, Uttar Dinajpur, Dakshin Dinajpur and Cooch Behar. There is more than 14.5 lakh tribal population in this region (which constitutes 1/3rd of the total tribal population of the State), of which 49.6 per cent are women. Jalpaiguri district has the highest concentration of tribal population as 14.56 per cent of its population is tribal population whereas Darjeeling has 4.60 per cent of its population as tribal population. -

Mal Assembly West Bengal Factbook

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.electionsinindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/WB-020-0619 ISBN : 978-93-5293-730-1 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 170 for the use of this publication. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency at a Glance | Features of Assembly as per 1-2 Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps 2 Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency in District | Boundaries 3-9 of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary Constituency | Town & Village-wise Winner Parties- 2019, 2016, 2014, 2011 and 2009 Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 10-16 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population | Towns and Villages by 17-18 Population Size | Sex Ratio (Total