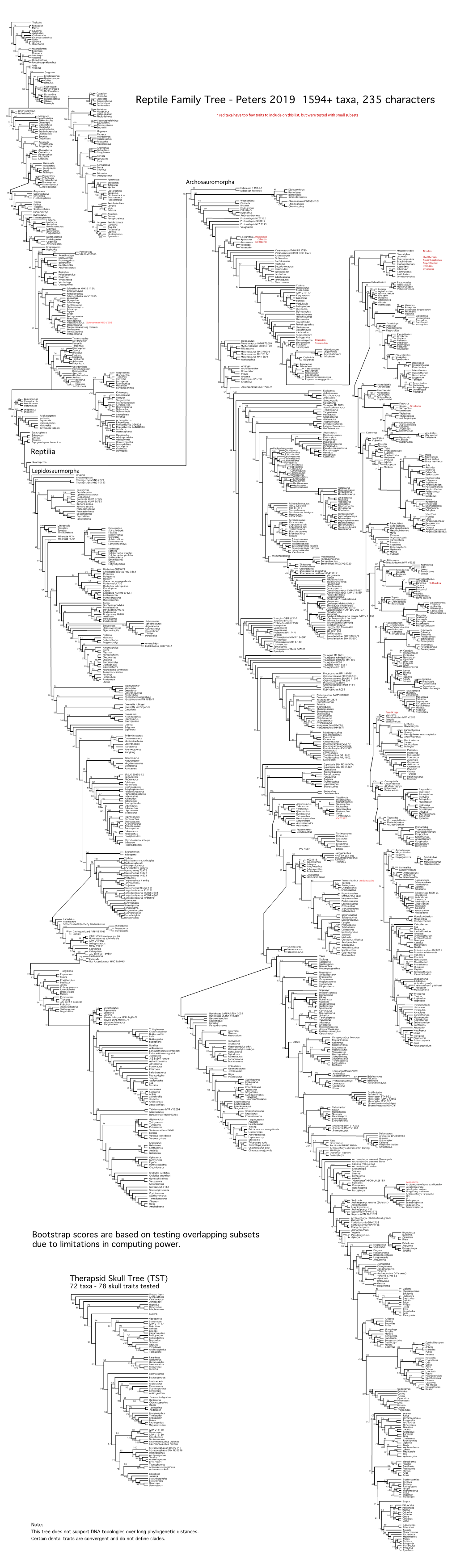

Reptile Family Tree

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sauropareion Anoplus, with a Discussion of Possible Life History

The postcranial skeleton of the Early Triassic parareptile Sauropareion anoplus, with a discussion of possible life history MARK J. MACDOUGALL, SEAN P. MODESTO, and JENNIFER BOTHA−BRINK MacDougall, M.J., Modesto, S.P., and Botha−Brink, J. 2013. The postcranial skeleton of the Early Triassic parareptile Sauropareion anoplus, with a discussion of possible life history. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 58 (4): 737–749. The skeletal anatomy of the Early Triassic (Induan) procolophonid reptile Sauropareion anoplus is described on the basis of three partial skeletons from Vangfontein, Middelburg District, South Africa. Together these three specimens preserve the large majority of the pectoral and pelvic girdles, articulated forelimbs and hindlimbs, and all but the caudal portion of the vertebral column, elements hitherto undescribed. Our phylogenetic analysis of the Procolophonoidea is consonant with previous work, positing S. anoplus as the sister taxon to a clade composed of all other procolophonids exclusive of Coletta seca. Previous studies have suggested that procolophonids were burrowers, and this seems to have been the case for S. anoplus, based on comparisons with characteristic skeletal anatomy of living digging animals, such as the presence of a spade−shaped skull, robust phalanges, and large unguals. Key words: Parareptilia, Procolophonidae, phylogenetic analysis, burrowing, Induan, Triassic, South Africa. Mark J. MacDougall [[email protected]], Department of Biology, Cape Breton University, Sydney, Nova Scotia, B1P 6L2, Canada and Department of Biology, University of Toronto at Mississauga, 3359 Mississauga Road, Ontario, L5L 1C6, Canada; Sean P. Modesto [[email protected]], Department of Biology, Cape Breton University, Sydney, Nova Scotia, B1P 6L2, Canada; Jennifer Botha−Brink [[email protected]], Karoo Palaeontology, National Museum, P.O. -

Ontogenetic Change in the Temporal Region of the Early Permian Parareptile Delorhynchus Cifellii and the Implications for Closure of the Temporal Fenestra in Amniotes

RESEARCH ARTICLE Ontogenetic Change in the Temporal Region of the Early Permian Parareptile Delorhynchus cifellii and the Implications for Closure of the Temporal Fenestra in Amniotes Yara Haridy*, Mark J. Macdougall, Diane Scott, Robert R. Reisz Department of Biology, University of Toronto Mississauga, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada * [email protected] a11111 Abstract A juvenile specimen of Delorhynchus cifellii, collected from the Early Permian fissure-fill deposits of Richards Spur, Oklahoma, permits the first detailed study of cranial ontogeny in this parareptile. The specimen, consisting of a partially articulated skull and mandible, exhib- OPEN ACCESS its several features that identify it as juvenile. The dermal tuberosities that ornament the dor- Citation: Haridy Y, Macdougall MJ, Scott D, Reisz sal side and lateral edges of the largest skull of D. cifellii specimens, are less prominent in RR (2016) Ontogenetic Change in the Temporal the intermediate sized holotype, and are absent in the new specimen. This indicates that the Region of the Early Permian Parareptile new specimen represents an earlier ontogenetic stage than all previously described mem- Delorhynchus cifellii and the Implications for bers of this species. In addition, the incomplete interdigitation of the sutures, most notably Closure of the Temporal Fenestra in Amniotes. PLoS ONE 11(12): e0166819. doi:10.1371/journal. along the fronto-nasal contact, plus the proportionally larger sizes of the orbit and temporal pone.0166819 fenestrae further support an early ontogenetic stage for this specimen. Comparisons Editor: Thierry Smith, Royal Belgian Institute of between this juvenile and previously described specimens reveal that the size and shape of Natural Sciences, BELGIUM the temporal fenestra in Delorhynchus appear to vary through ontogeny, due to changes in Received: July 18, 2016 the shape and size of the bordering cranial elements. -

The Anatomy of Asilisaurus Kongwe, a Dinosauriform from the Lifua

THE ANATOMICAL RECORD (2019) The Anatomy of Asilisaurus kongwe,a Dinosauriform from the Lifua Member of the Manda Beds (~Middle Triassic) of Africa 1 2 3 STERLING J. NESBITT , * MAX C. LANGER, AND MARTIN D. EZCURRA 1Department of Geosciences, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, Virginia 2Departamento de Biologia, Universidade de Sao~ Paulo, Ribeirao~ Preto, Brazil 3Sección Paleontología de Vertebrados CONICET—Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales “Bernardino Rivadavia”, Buenos Aires, Argentina ABSTRACT The diagnosis of Dinosauria and interrelationships of the earliest dino- saurs relies on careful documentation of the anatomy of their closest rela- tives. These close relatives, or dinosaur “precursors,” are typically only documented by a handful of fossils from across Pangea and nearly all speci- mens are typically missing important regions (e.g., forelimbs, pelves, skulls) that appear to be important to help resolving the relationships of dinosaurs. Here, we fully describe the known skeletal elements of Asilisaurus kongwe, a dinosauriform from the Middle Triassic Manda Beds of the Ruhuhu Basin of Tanzania. The taxon is known from many disarticulated and partially articulated remains and, most importantly, from a spectacularly preserved associated skeleton of an individual containing much of the skull, pectoral and pelvic girdles, forelimb and hindlimb, and parts of the vertebral column including much of the tail. The unprecedented detail of the anatomy indi- cates that Asilisaurus kongwe had a unique skull that was short and had both a premaxillary and dentary edentulous margin, but retained a number of character states plesiomorphic for Archosauria, including a crocodylian- like ankle configuration and a rather short foot with well-developed meta- tarsals I and V. -

Reptile Family Tree

Reptile Family Tree - Peters 2015 Distribution of Scales, Scutes, Hair and Feathers Fish scales 100 Ichthyostega Eldeceeon 1990.7.1 Pederpes 91 Eldeceeon holotype Gephyrostegus watsoni Eryops 67 Solenodonsaurus 87 Proterogyrinus 85 100 Chroniosaurus Eoherpeton 94 72 Chroniosaurus PIN3585/124 98 Seymouria Chroniosuchus Kotlassia 58 94 Westlothiana Casineria Utegenia 84 Brouffia 95 78 Amphibamus 71 93 77 Coelostegus Cacops Paleothyris Adelospondylus 91 78 82 99 Hylonomus 100 Brachydectes Protorothyris MCZ1532 Eocaecilia 95 91 Protorothyris CM 8617 77 95 Doleserpeton 98 Gerobatrachus Protorothyris MCZ 2149 Rana 86 52 Microbrachis 92 Elliotsmithia Pantylus 93 Apsisaurus 83 92 Anthracodromeus 84 85 Aerosaurus 95 85 Utaherpeton 82 Varanodon 95 Tuditanus 91 98 61 90 Eoserpeton Varanops Diplocaulus Varanosaurus FMNH PR 1760 88 100 Sauropleura Varanosaurus BSPHM 1901 XV20 78 Ptyonius 98 89 Archaeothyris Scincosaurus 77 84 Ophiacodon 95 Micraroter 79 98 Batropetes Rhynchonkos Cutleria 59 Nikkasaurus 95 54 Biarmosuchus Silvanerpeton 72 Titanophoneus Gephyrostegeus bohemicus 96 Procynosuchus 68 100 Megazostrodon Mammal 88 Homo sapiens 100 66 Stenocybus hair 91 94 IVPP V18117 69 Galechirus 69 97 62 Suminia Niaftasuchus 65 Microurania 98 Urumqia 91 Bruktererpeton 65 IVPP V 18120 85 Venjukovia 98 100 Thuringothyris MNG 7729 Thuringothyris MNG 10183 100 Eodicynodon Dicynodon 91 Cephalerpeton 54 Reiszorhinus Haptodus 62 Concordia KUVP 8702a 95 59 Ianthasaurus 87 87 Concordia KUVP 96/95 85 Edaphosaurus Romeria primus 87 Glaucosaurus Romeria texana Secodontosaurus -

University of Birmingham a New Dinosaur With

University of Birmingham A new dinosaur with theropod affinities from the Late Triassic Santa Maria Formation, South Brazil Marsola, Julio; Bittencourt, Jonathas; Butler, Richard; Da Rosa, Atila; Sayao, Juliana; Langer, Max DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2018.1531878 License: None: All rights reserved Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Marsola, J, Bittencourt, J, Butler, R, Da Rosa, A, Sayao, J & Langer, M 2019, 'A new dinosaur with theropod affinities from the Late Triassic Santa Maria Formation, South Brazil', Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, vol. 38, no. 5, e1531878. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2018.1531878 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Checked for eligibility: 25/07/2018 This is the accepted manuscript for a forthcoming publication in Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. -

Width Measured at the Level of Anterior Squamosal/Parietal Suture

Fig. 5. (A) Scaling of brain vault size (width measured at the level of anterior squamosal/parietal suture) relative to skull size (measured at the distance between the left versus right temporomandibular joints). This shows that allometry of small size of Hadrocodium, by itself, is not sufficient to account for its very large braincase. Had-rocodium's brain vault is larger (wider) than expected for the crown-group mammals with similar skull width from the allometrical regression. By contrast, all contemporaneous mammaliaforms (triangles: Sinoconodon, Morganucodon, and Haldanodon) with the postdentary trough and meckelian groove have smaller (narrower) brain vaults than those living mammal taxa (and Hadrocodium) of comparable skull size. The brain vault is narrower in nonmammaliaform cynodonts (squares: Chaliminia, Massetoganthus, Probelesodon, Probainognathus, and Yunnanodon) than in mammaliaform stem taxa and much narrower than expected for crown group mammals of similar size. The allometric equation (natural logarithmic scale) for the brain vault width (Y) to the skull width at the level of TMJ (X) for species in the mammalian crown groups (circles: 37 living and 8 fossil species): Y =0.98X -0.31 (R2 – 0.715). Data from cynodonts, mammaliaforms, and Hadrocodium are added second arily for comparison with the regression of extant and fossil species of mammalian crown group. (B) Estimated body-size distributions of mammaliaform insectivores in the Early Jurassic Lufeng fauna [following method of Gingerich (50)]. The estimated 2-g body mass of Hadrocodium is in strong contrast to its contemporary mammaliaforms of the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic, such as Sinconodon (from ~13 to ~517 g, based on skull length from 22 to 62 mm) and Morganucodon (from 27 to 89 g, based on skull length from 27 to 38 mm). -

A Small Lepidosauromorph Reptile from the Early Triassic of Poland

A SMALL LEPIDOSAUROMORPH REPTILE FROM THE EARLY TRIASSIC OF POLAND SUSAN E. EVANS and MAGDALENA BORSUK−BIAŁYNICKA Evans, S.E. and Borsuk−Białynicka, M. 2009. A small lepidosauromorph reptile from the Early Triassic of Poland. Palaeontologia Polonica 65, 179–202. The Early Triassic karst deposits of Czatkowice quarry near Kraków, southern Poland, has yielded a diversity of fish, amphibians and small reptiles. Two of these reptiles are lepido− sauromorphs, a group otherwise very poorly represented in the Triassic record. The smaller of them, Sophineta cracoviensis gen. et sp. n., is described here. In Sophineta the unspecial− ised vertebral column is associated with the fairly derived skull structure, including the tall facial process of the maxilla, reduced lacrimal, and pleurodonty, that all resemble those of early crown−group lepidosaurs rather then stem−taxa. Cladistic analysis places this new ge− nus as the sister group of Lepidosauria, displacing the relictual Middle Jurassic genus Marmoretta and bringing the origins of Lepidosauria closer to a realistic time frame. Key words: Reptilia, Lepidosauria, Triassic, phylogeny, Czatkowice, Poland. Susan E. Evans [[email protected]], Department of Cell and Developmental Biology, Uni− versity College London, Gower Street, London, WC1E 6BT, UK. Magdalena Borsuk−Białynicka [[email protected]], Institut Paleobiologii PAN, Twarda 51/55, PL−00−818 Warszawa, Poland. Received 8 March 2006, accepted 9 January 2007 180 SUSAN E. EVANS and MAGDALENA BORSUK−BIAŁYNICKA INTRODUCTION Amongst living reptiles, lepidosaurs (snakes, lizards, amphisbaenians, and tuatara) form the largest and most successful group with more than 7 000 widely distributed species. The two main lepidosaurian clades are Rhynchocephalia (the living Sphenodon and its extinct relatives) and Squamata (lizards, snakes and amphisbaenians). -

Tiago Rodrigues Simões

Diapsid Phylogeny and the Origin and Early Evolution of Squamates by Tiago Rodrigues Simões A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in SYSTEMATICS AND EVOLUTION Department of Biological Sciences University of Alberta © Tiago Rodrigues Simões, 2018 ABSTRACT Squamate reptiles comprise over 10,000 living species and hundreds of fossil species of lizards, snakes and amphisbaenians, with their origins dating back at least as far back as the Middle Jurassic. Despite this enormous diversity and a long evolutionary history, numerous fundamental questions remain to be answered regarding the early evolution and origin of this major clade of tetrapods. Such long-standing issues include identifying the oldest fossil squamate, when exactly did squamates originate, and why morphological and molecular analyses of squamate evolution have strong disagreements on fundamental aspects of the squamate tree of life. Additionally, despite much debate, there is no existing consensus over the composition of the Lepidosauromorpha (the clade that includes squamates and their sister taxon, the Rhynchocephalia), making the squamate origin problem part of a broader and more complex reptile phylogeny issue. In this thesis, I provide a series of taxonomic, phylogenetic, biogeographic and morpho-functional contributions to shed light on these problems. I describe a new taxon that overwhelms previous hypothesis of iguanian biogeography and evolution in Gondwana (Gueragama sulamericana). I re-describe and assess the functional morphology of some of the oldest known articulated lizards in the world (Eichstaettisaurus schroederi and Ardeosaurus digitatellus), providing clues to the ancestry of geckoes, and the early evolution of their scansorial behaviour. -

Final Copy 2019 10 01 Herrera

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Herrera Flores, Jorge Alfredo A Title: The macroevolution and macroecology of Mesozoic lepidosaurs General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Herrera Flores, Jorge Alfredo A Title: The macroevolution and macroecology of Mesozoic lepidosaurs General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. -

A Beaked Herbivorous Archosaur with Dinosaur Affinities from the Early Late Triassic of Poland

Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 23(3):556±574, September 2003 q 2003 by the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology A BEAKED HERBIVOROUS ARCHOSAUR WITH DINOSAUR AFFINITIES FROM THE EARLY LATE TRIASSIC OF POLAND JERZY DZIK Instytut Paleobiologii PAN, Twarda 51/55, 00-818 Warszawa, Poland, [email protected] ABSTRACTÐAn accumulation of skeletons of the pre-dinosaur Silesaurus opolensis, gen. et sp. nov. is described from the Keuper (Late Triassic) claystone of KrasiejoÂw in southern Poland. The strata are correlated with the late Carnian Lehrberg Beds and contain a diverse assemblage of tetrapods, including the phytosaur Paleorhinus, which in other regions of the world co-occurs with the oldest dinosaurs. A narrow pelvis with long pubes and the extensive development of laminae in the cervical vertebrae place S. opolensis close to the origin of the clade Dinosauria above Pseudolagosuchus, which agrees with its geological age. Among the advanced characters is the beak on the dentaries, and the relatively low tooth count. The teeth have low crowns and wear facets, which are suggestive of herbivory. The elongate, but weak, front limbs are probably a derived feature. INTRODUCTION oped nutrient foramina in its maxilla. It is closely related to Azendohsaurus from the Argana Formation of Morocco (Gauf- As is usual in paleontology, with an increase in knowledge fre, 1993). The Argana Formation also has Paleorhinus, along of the fossil record of early archosaurian reptiles, more and with other phytosaurs more advanced than those from Krasie- more lineages emerge or extend their ranges back in time. It is joÂw (see Dutuit, 1977), and it is likely to be somewhat younger. -

Technical Program

MONDAY, JULY 30 11:00AM 1801770 Polysaccharide Composites as Barrier Materials Jeffrey Catchmark, Penn State, University Park, PA TECHNICAL PROGRAM United States (Presenter: Jeffrey Catchmark) (Jeffrey MONDAY, JULY 30 Catchmark, Kai Chi, Snehasish Basu) 9:30AM-12:00PM 11:15AM 1800994 Production and characterization of in situ synthesis of silver nanoparticles into TEMPO-mediated oxi- The purpose of these Sessions is the open exchange of dized bacterial cellulose and their antivibriocidal ac- ideas, therefore, remarks made by a participant or mem- tivity against shrimp pathogens Sivaramasamy Elayaraja, Zhejiang University, ber of the audience cannot be quoted or attributed to ei- Hangzhou, Zhejiang China, People’s Republic of (Pre- ther the individual or the individuals’ company. NO senter: Sivaramasamy Elayaraja) (Sivaramasamy Ela- RECORDING of the participants’ remarks or discussion is yaraja, Liu Gang, Jianhai Xiang, Songming Zhu) 11:30AM 1801330 Design, Development, Evaluation of Gum Arabic permitted. Pictures of any material shown here are not Milling Machine permitted. Eyad Eltigani, University of Khartoum, Khartoum, Khar- toum Sudan (Presenter: Eyad Eltigani) (Eyad Mohamed Eltigani Abuzeid, Khalid Elgassim Mohamed Ahmed, In respect for the presenters and the people attending the Hossamaldein Fadoul Brima) conference, ASABE would request that anyone having a 11:45AM 1801112 The Design of Longitudinal - axial cylinder for the combine pager, cell phone, or other electronic device please turn Meng Fanhu, Sandong University Technology, Zibo, them off. If your situation does not allow for these devices Shandong province China, People’s Republic of (Pre- to be turned off, please reseat yourself close to an exit senter: Meng Fanhu) (Meng Fanhu) such that everyone can benefit from the information pre- sented here without disruption. -

Rapid and Early Post-Flood Mammalian Diversification Videncede in the Green River Formation

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 6 Print Reference: Pages 449-457 Article 36 2008 Rapid and Early Post-Flood Mammalian Diversification videncedE in the Green River Formation John H. Whitmore Cedarville University Kurt P. Wise Southern Baptist Theological Seminary Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Whitmore, John H. and Wise, Kurt P. (2008) "Rapid and Early Post-Flood Mammalian Diversification Evidenced in the Green River Formation," The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 6 , Article 36. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol6/iss1/36 In A. A. Snelling (Ed.) (2008). Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Creationism (pp. 449–457). Pittsburgh, PA: Creation Science Fellowship and Dallas, TX: Institute for Creation Research. Rapid and Early Post-Flood Mammalian Diversification Evidenced in the Green River Formation John H. Whitmore, Ph.D., Cedarville University, 251 N. Main Street, Cedarville, OH 45314 Kurt P. Wise, Ph.D., Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2825 Lexington Road.