Recent Decisions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Problem of Delay in the Contract Formation Process: a Comparative Study of Contract Law Mikio Yamaguchi T

Cornell International Law Journal Volume 37 Article 3 Issue 2 2004 The rP oblem of Delay in the Contract Formation Process: A Comparative Study of Contract Law Mikio Yamaguchi Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cilj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Yamaguchi, Mikio (2004) "The rP oblem of Delay in the Contract Formation Process: A Comparative Study of Contract Law," Cornell International Law Journal: Vol. 37: Iss. 2, Article 3. Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cilj/vol37/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell International Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Problem of Delay in the Contract Formation Process: A Comparative Study of Contract Law Mikio Yamaguchi T Introduction ..................................................... 358 I. Law Applicable to the Problem of Delay in the United States .................................................... 3 6 1 A. Structure of Applicable Law ........................... 361 B. Priority of the Applicable Law ........................ 362 II. Comparative Study of the Contract Formation Process ..... 363 A. Legal Structure of the Contract Formation Process ..... 363 1. Structure of the Contract Formation Process Under the Comm on Law ................................. 363 2. Structure of the Contract Formation Process from a Comparative Perspective ........................... 364 B. A Major Function of the Common Law in the Contract Form ation Process .................................... 365 1. Common Law Rules and Principles That Reflect the Balancing Function ................................ 365 2. Balancing Function from a Comparative Perspective ....................................... -

Introduction to Law and Legal Reasoning Law Is

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION TO LAW AND LEGAL REASONING LAW IS "MAN MADE" IT CHANGES OVER TIME TO ACCOMMODATE SOCIETY'S NEEDS LAW IS MADE BY LEGISLATURE LAW IS INTERPRETED BY COURTS TO DETERMINE 1)WHETHER IT IS "CONSTITUTIONAL" 2)WHO IS RIGHT OR WRONG THERE IS A PROCESS WHICH MUST BE FOLLOWED (CALLED "PROCEDURAL LAW") I. Thomas Jefferson: "The study of the law qualifies a man to be useful to himself, to his neighbors, and to the public." II. Ask Several Students to give their definition of "Law." A. Even after years and thousands of dollars, "LAW" still is not easy to define B. What does law Consist of ? Law consists of enforceable rule governing relationships among individuals and between individuals and their society. 1. Students Need to Understand. a. The law is a set of general ideas b. When these general ideas are applied, a judge cannot fit a case to suit a rule; he must fit (or find) a rule to suit the unique case at hand. c. The judge must also supply legitimate reasons for his decisions. C. So, How was the Law Created. The law considered in this text are "man made" law. This law can (and will) change over time in response to the changes and needs of society. D. Example. Grandma, who is 87 years old, walks into a pawn shop. She wants to sell her ring that has been in the family for 200 years. Grandma asks the dealer, "how much will you give me for this ring." The dealer, in good faith, tells Grandma he doesn't know what kind of metal is in the ring, but he will give her $150. -

2000-2001,26 L.Ed.2D 387 (1970); Monroe, Id

QUESTION 1 Denver Electronic Business, Inc. (Denver) designs and markets computer software. In order to expand its business, Denver borrowed funds from First Bank & Trust Company ( Bank). Denver and Bank signed a security agreement which granted Bank a security interest in all Denver's "equipment, inventory, computer software and designs, now owned or hereafter acquired or developed." Bank also had Denver sign a financing statement which identified the collateral in the same terms. Bank promptly filed the financing statement with the appropriate filing offices of the state and county in which Denver is headquartered and does business. A few months later, Denver replaced its employees' computers and sold the old computers to Computer Sales, Inc. (Computer Sales), a business which buys and sells used computer equipment. A few weeks later, Betty Buyer (Buyer)purchased one of these machines from Computer Sale's retail store. Denver used $1,000 of the proceeds from the sale of its old computers to buy 100 shares of stock in TransWord, Corp. Denver received a fully executed stock certificate for the 100 shares from TransWord in Denver's name. Unfortunately, Denver's business failed, forcing Denver to file bankruptcy. At the time of the filing, Denver's major asset was the successful word processing program it had developed, "Word-GO." QUESTIONS: 1. Discuss who has priority in Word-GO and the TransWord stock: Bank or the bankruptcy trustee. 2. Discuss whether Bank may recover the computer Buyer purchased from Computer Sales. QUESTION 2 Andy was looking for a building suitable for an auto repair business. -

Vallario Contract Formation Course Materials Fall 2020 Table of Contents

Vallario Contract Formation Course Materials Fall 2020 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 2 Sources of Law .............................................................................................................................2 Case briefing .................................................................................................................................3 Legal analysis and IRAC ..............................................................................................................3 MODULE ONE: OFFER ..................................................................................................... 7 A. Offer ........................................................................................................................................7 B. Destruction of the Offer ............................................................................................................9 C. Irrevocable Offers ................................................................................................................. 12 MODULE TWO: COMMON LAW ACCEPTANCE ........................................................ 13 MODULE THREE: OFFER AND ACCEPTANCE UNDER THE UCC ........................... 16 A. Offer and Acceptance under UCC ...................................................................................... 17 B. Battle of the Forms ................................................................................................................ -

A Refresher Course in Cause J

Louisiana Law Review Volume 12 | Number 1 November 1951 A Refresher Course in Cause J. Denson Smith Repository Citation J. Denson Smith, A Refresher Course in Cause, 12 La. L. Rev. (1951) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol12/iss1/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Refresher Course in Cause J. Denson Smith* One of the most significant and perhaps troublesome prob- lems that will confront the drafters of a Projet of a Revised Civil Code, as envisioned by Act 335 of 1948, will be what to do about the doctrine of cause in Louisiana's contract law. This will necessarily involve also deciding what to do about consideration that, aided by a fifth column operating from the code itself, has infiltrated from the common law. Available choices will include whether to retain our traditional doctrine with an infusion of new vigor afforded chiefly by pruning away the confusing admixture of consideration; whether to yield to the latter doc- trine as a substitute; or whether simply to undertake to avoid any mention of cause and set up rules designed to make its application unnecessary. It may be admitted at the outset that we can get along without cause if we want to. Other jurisdictions that have drawn their law from the civilian well presumably have done so.' Yet we cannot get away from the problems that must be solved by the application of principles rooted deep in the essence of cause. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT of MAINE JUSTIN ANGELO, Plaintiff, V. CAMPUS CREST at ORONO, LLC, Defendant/Third- Party P

Case 1:15-cv-00469-NT Document 88 Filed 04/30/18 Page 1 of 9 PageID #: <pageID> UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF MAINE JUSTIN ANGELO, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Docket No. 1:15-cv-469-NT ) CAMPUS CREST AT ORONO, LLC, ) ) Defendant/Third- ) Party Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) ) TOWN OF ORONO POLICE DEPT. ) ) Third-Party ) Defendant. ) ORDER ON THIRD-PARTY DEFENDANT’S MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT Before me is the Town of Orono Police Department’s (“OPD”) motion for summary judgment. (ECF No. 82.) Campus Crest at Orono, LLC (“Campus Crest”) sued the OPD for breach of contract and implied contractual indemnification. Third- Party Complaint (ECF No. 30.) The OPD argues that it cannot be liable for either count because it had no contract with Campus Crest. For the following reasons, the motion for summary judgment is GRANTED. FACTUAL BACKGROUND The following account is taken from the parties’ statements of material facts, credited only to the extent that the facts are either admitted or supported by the Case 1:15-cv-00469-NT Document 88 Filed 04/30/18 Page 2 of 9 PageID #: <pageID> record in accordance with Local Rule 56. I take the facts in the light most favorable to the non-movant. Campus Crest owns and operates an apartment complex called The Grove in Orono, Maine. SMF ¶¶ 2-3 (ECF No. 87). After The Grove opened in 2012, there were a number of large gatherings that required a police response. SMF ¶ 4. The OPD warned Campus Crest of an Orono ordinance under which the OPD could seek reimbursement as a penalty for large gatherings that required multiple police agencies to respond. -

Contracts 8 24

QUESTION 3 On Mayl, Buyer received the following letter: Dear Buyer: I have decided to give up my ranch and move to town. I thought that you might consider buying it from me. I will sell it to you for its current market value, $80,000. Call me by May 10. I will keep this proposal open, and will not withdraw it, until after that date. IS/ Seller The next day, Buyer mentioned to a friend, Mary, that he was considering buying the ranch. Mary responded that an acquaintance of hers, Jody, also had received an offer from Seller to purchase the ranch. Buyer immehately went home and prepared a letter of acceptance, addressed to Seller, and deposited it in the mail at 9:30 A.M. At 10:OO A.M. on May 2, Seller entered into a written agreement with Jody for the purchase of the ranch. At 2:00 P.M. on May 2, Buyer called Seller to arrange for a survey of the ranch. Seller informed Buyer that he had already sold the ranch. Upon hearing this, Buyer exclaimed, "We have a deal. I sent you an acceptance this morning by mail." QUESTION: Discuss whether there is a contract between Buyer and Seller and the basis for your conclusion. DISCUSSION FOR QUESTION 3 An offer is a manifestation of willingness to enter into a bargain so made as to justify another person in understandmg that his assent to that bargain is invited and will conclude it. Res.2d Contracts 8 24. In this case Seller's letter is an offer, since under the objective test of intent, a reasonable person in Buyer's position would understand that Seller was in fact seeking Buyer's assent to his invitation. -

LGST 101 Syllabus

LGST 101-901 Summer 2013 Monday-Thursday 10:40 – 12 :15 INTRODUCTION TO LAW AND THE LEGAL PROCESS Professor: Nichols Office: 655 Huntsman Hall Office Phone: 898-9369 Assigned Reading: You must obtain a course pack through study.net/Wharton Reprographics. Please do the assigned reading before class, and please bring the course pack to class with you. This syllabus is subject to change at the discretion of the instructor – in the event of a change you will be notified in class. Grading: Class preparation, participation and attendance will count 30% of your grade. Class participation includes attending class, on time. Class participation also includes evidence of preparation, and thoughtful contribution to the class discussion. There will be one midterm exam counting 35% of your grade and a final exam counting 35% of your grade. TOPICAL ASSIGNMENTS I. AN INTRODUCTION TO LAW AND LEGAL SYSTEMS May 20; Class 1: Introduction: What is Law? Readings: 1. Introduction to Law 2. There are No Secret Books May 21; Class 2: What is International Law? Reading: 3. Sources of International Law May 22; Class 3: Legal Reasoning Readings: 4. An Introductory Note on Jurisprudence 5. The Case of the Speluncean Explorers May 23; Class 4: Property: Personal Property Readings: 6. You are What You Own 7. Popov v. Hayashi 8. Swift v. Gifford 9. Keron v. Cashman May 28; Class 5: Property: Intellectual Property Readings: 10. The Strategist’s Dream 11. Four Kinds of Intellectual Property in the United States 12. Company Isn’t Afraid to Take Copycats to Court 13. Suing Your Customers: A Winning Business Strategy? 14. -

Contract Formation Under Article 2 of the Uniform Commerical Code Carolyn M

Marquette Law Review Volume 61 Article 1 Issue 2 Winter 1977 Contract Formation Under Article 2 of the Uniform Commerical Code Carolyn M. Edwards Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Carolyn M. Edwards, Contract Formation Under Article 2 of the Uniform Commerical Code, 61 Marq. L. Rev. 215 (1977). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol61/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARQUETTE LAW REVIEW Vol. 61 Winter 1977 No. 2 CONTRACT FORMULATION UNDER ARTICLE 2 OF THE UNIFORM COMMERCIAL CODE CAROLYN M. EDWARDS* Today, Article 2 of the Uniform Commercial Code' is the principal statute governing sales of goods2 in every state except Louisiana. Although the article made fundamental changes in the law of sales, it did not totally displace common law princi- ples. Indeed, some provisions of the statute codify common law rules. The shortcoming of the statute, however, is that it is not self-executing; it is silent on some issues and ambiguous as to others. Under these circumstances courts have resorted to com- mon law, citing Article 1, section 1-103,1 which provides that the principles of law and equity may supplement the Code unless such principles are displaced by particular provisions. * Assistant Professor of Law, Marquette University Law School; B.A. -

Uniform Commercial Code and Contract Law: Some Selected Problems

THE UNIFORM COMMERCIAL CODE AND CONTRACT LAW: SOME SELECTED PROBLEMS TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ............................................................. 837 PART I. FORMATION OF A CONTRACT-AccEPTANCE ........................... 839 Acceptance by the Seller ..................................... 839 Acceptance Which Varies From the Offer .................... 850 Conclusion .................................................. 864 PART II. TENDER OF NONCONFORMING GOODS-BuYER's DUTIES UPON RIGHT- FUL REJECTION .............................................. 864 Buyer's Preliminary Duties Upon Rejection ................... 865 Duties of a Merchant Buyer ................................ 866 Merchant Buyer's Duties as to Perishable Goods ................ 869 Exceptions and Special Cases ................................ 872 Conclusion .................................................. 880 PART III. PERFORMANcE-THE DOCTRINE OF IMPOSSIBILITY .................... 880 Adjusting a Disrupted Deal: Excusing the Seller Because of Supervening Facts ......................................... 881 Excuse: Failure of Presupposed Conditions .................... 885 Selected Problems Involving Impracticability ................... 890 Procedure Upon Claim of Excuse .............................. 900 Buyer's Excuse When Contract Has Lost Its Ultimate Value: Frustration ................................................ 904 Conclusion ................................................... 905 PART IV. TRAFFIC IN CONTRACT RIGHTS AND DUTIES-ASSIGNMENT AND DELEGATION -

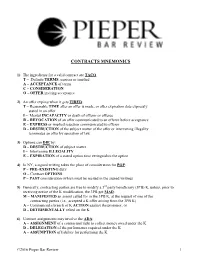

Contracts Mnemonics

CONTRACTS MNEMONICS 1) The ingredients for a valid contract are TACO: T – Definite TERMS, express or implied A – ACCEPTANCE of terms C – CONSIDERATION O – OFFER inviting acceptance 2) An offer expires when it gets TIRED: T – Reasonable TIME after an offer is made, or after expiration date expressly stated in an offer I – Mental INCAPACITY or death of offeror or offeree R – REVOCATION of an offer communicated to an offeree before acceptance E – EXPRESS or implied rejection communicated to offeror D – DESTRUCTION of the subject matter of the offer or intervening illegality terminates an offer by operation of law 3) Options can DIE by: D – DESTRUCTION of subject matter I – Intervening ILLEGALITY E – EXPIRATION of a stated option time extinguishes the option 4) In NY, a signed writing takes the place of consideration for POP: P – PRE–EXISTING duty O – Contract OPTIONS P – PAST consideration (which must be recited in the signed writing) 5) Generally, contracting parties are free to modify a 3rd party beneficiary (3PB) K, unless, prior to receiving notice of the K modification, the 3PB got MAD: M – MANIFESTED an assent called for in the 3PB K, at the request of one of the contracting parties (i.e., accepted a K offer arising from the 3PB K) A – Commenced a breach of K ACTION against the promisor, or D – DETRIMENTALLY relied on the K 6) Contract assignments may involve the ADA: A – ASSIGNMENT of a contractual right to collect money owed under the K D – DELEGATION of the performance required under the K A – ASSUMPTION of liability for performing -

The Bible and Critical Theory Articles

ARTICLES THE B IBLE AND CRITICAL THEORY Toward a Radical Naturalistic and Humanistic Interpretation of the Abrahamic Religions In Search for the Wholly Other than the Horror and Terror of Nature and History Rudolf J. Siebert Western Michigan University Edited by Michael R. Ott Grand Valley State University In this sweeping work, Rudolf Siebert goes beyond and develops further and creatively applies the argument found in his recent three volume Manifesto in a relatively succinct form. Drawing upon the rich resources of the Critical Theory of Society of the Frankfurt School but also the vast tradition of critical philosophy and theology, Siebert offers a ‘critical’ analysis. A critical approach (from the Greek kritikos, able to discern) implies that religious phenomena are examined according to both their positive and negative impacts, with help from the critical theory of society. A critical approach is not neutral. Critical theorists of religion are engaged in informed assessments which enable action in the public sphere. Siebert’s focus is nothing less than some aspects of the three Abrahamic Religions - Judaism, Christianity and Islam - and their sacred writings - the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament and The Holy Qur’an. According to the Rabbis, the modern antagonism between the sacred and the profane, or between the religious and the secular, had been unknown to the Torah, or even - so the dialectical religiologist may add - to the Tanakh, or to any other ancient sacred writing.1 Everything we do, so the Rabbis thought, had the potential of being holy, and according to the Torah and the Talmud those people who thought that there was no God, and that the world of nature and of man – family, society, state, history and culture – was entirely secular and profane, were considered to be foolish, false, corrupt, vile, evil, unwise, tainted, ignorant, stupid, unclean, impure, lawless, immoral, wicked, evildoers.