The Atwater Market

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring Office Market Report 2018 Greater Montreal

SPRING OFFICE MARKET REPORT 2018 GREATER MONTREAL Image Credit: Avison Young Québec Inc. PAGE 1 SPRING 2018 OFFICE MARKET REPORT | GREATER MONTREAL SPRING OFFICE MARKET REPORT 2018 GREATER MONTREAL Office market conditions have Class-A availability Downtown been very stable in the Greater Montreal reached 11.7% at the Montreal Area (GMA) over the end of the first quarter, which past year, but recent news lead represents an increase of only 20 to believe this could change basis points year-over-year. drastically over the years to come as major projects were announced Landlords who invested in their and the construction of Montreal’s properties and repositioned their Réseau Express Métropolitain assets in Downtown Montreal over (REM) began. New projects and the past years are benefiting from future developments are expected their investments as their portfolios to shake up Montreal’s real estate show more stability and success markets and put a dent in the than most. stability observed over the past quarters. It is the case at Place Ville Marie, where Ivanhoé Cambridge is Even with a positive absorption of attracting new tenants who nearly 954,000 square feet (sf) of are typically not interested in space over the last 12 months, the traditional office space Downtown total office availability in the GMA Montreal, such as Sid Lee, who will remained relatively unchanged be occupying the former banking year-over-year with the delivery of halls previously occupied by the new inventory, reaching 14.6% at Royal Bank of Canada. Vacancy and the end of the first quarter of 2018 availability in the iconic complex from 14.5% the previous year. -

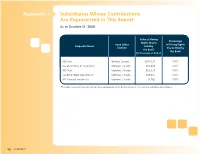

Subsidiaries Whose Contributions Are Represented in This Report As at October 31, 2009

Appendix 1 Subsidiaries Whose Contributions Are Represented In This Report As at October 31, 2009 Value of Voting Percentage Rights Shares Head Office of Voting Rights Corporate Name Held by Location Shares Held by the Bank1 the Bank (In thousands of dollars) B2B Trust Toronto, Canada $286,530 100% Laurentian Trust of Canada Inc. Montreal, Canada $85,409 100% LBC Trust Montreal, Canada $62,074 100% Laurentian Bank Securities Inc. Montreal, Canada $39,307 100% LBC Financial Services Inc. Montreal, Canada $4,763 100% 1 The book value of shares with voting rights corresponds to the Bank’s interest in the equity of subsidiary shareholders. 23 APPENDIX Appendix 2 Employee Population by Province and Status As at October 31, 2009 Province Full-Time Part-Time Temporary Total Alberta 10 – – 10 British Columbia 6 – – 6 Newfoundland 1 – – 1 Nova Scotia 1 – – 1 Ontario 369 4 81 454 Québec 2,513 617 275 3,405 TOTAL 2,900 621 356 3,877 24 APPENDIX Appendix 3 Financing by commercial client loan – Amounts authorized during the year As at October 31, 2009 0 − 25,000 − 100,000 − 250,000 − 500,000 − 1,000,000 − 5,000,000 Province Total 24,999 99,999 249,999 499,999 999,999 4,999,999 and over British Columbia Authorized amount 168,993 168,993 Number of clients 1 1 New Brunswick Authorized amount Number of clients Ontario Authorized amount 151,900 1,024,068 3,108,000 8,718,154 30,347,394 189,266,928 296,349,931 528,966,375 Number of clients 16 18 20 26 43 90 29 242 Québec Authorized amount 16,050,180 92,265,280 172,437,714 229,601,369 267,927,253 689,934,205 -

Download the Brochure

MODERN CONDOS WITH MONTREAL CHARACTER Master the art of boutique living in downtown Montreal with Enticy, affordable condos with zero compromise on quality, comfort or style. Inspired by contemporary boutique hotels and Montreal’s unique character, the project combines the best of urban life with the modern amenities that matter. Take your pick of studio, one- or two-bedroom units, each boasting an open-plan design, plenty of natural light, top-quality features and unbeatable views of the city. A prime location Enticy is ideally situated on the corner of René- Lévesque boulevard and Mackay Street, in a dynamic and diverse community that is rich in history and immersed in local culture. Live just steps away from shops, malls, restaurants, museums, metro stations, two universities and the best of city life. A smart investment Enticy offers incredible value for money thanks to its prime location and boutique style, coupled with its affordable pricing and low condo fees. It is also a smart and solid investment, perfect for first-time buyers, students studying at Concordia or McGill, investors, or professionals looking for a place close to work in the city. A quality development Every detail at Enticy has been thoughtfully designed for your comfort and convenience, from the rooftop pool and fully equipped gym to the top-quality construction, and high-end fixtures and features. Inside and out, Enticy takes excellence to a new level. LIVE STEPS FROM THE ACTION Enticy is a unique 24-storey building with an historical façade and contemporary design, creating a contrast between old and new that pays tribute to the surrounding neighbourhood. -

The Churches of the Europeans in Québec

The Europeans in Québec Lower Canada and Québec The Churches of the Europeans in Québec Compiled by Jacques Gagné - [email protected] Updated: April 2012 The Europeans in Québec Lower Canada and Québec The Churches of the Europeans in Québec Churches of the Scandinavian, Baltic States, Germanic, Icelandic people in Montréal, Québec City, Lower St. Lawrence, Western Québec, Eastern Townships, Richelieu River Valley - The churches of immigrants from Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland, Estonia, Latvia. Lithuania, Iceland, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, Switzerland, Austria plus those from Eastern European countries - Churches which were organized in Québec from 1621 to 2005. Also included within this document you will find a number of book titles relating to the subject. Major Repositories quoted within this compilation QFHS - Quebec Family History Society in Pointe Claire BAnQ - Bibliothèque Archives nationales du Québec in Montréal Ancestry.ca - The Canadian division of Ancestry.com Lutheran Church-Canada - East District Conference Lutheran Church-Canada - Montreal Lutheran Council United Church of Canada Archives- Montreal & Ottawa Conference United Church of Canada Archives - Montreal Presbytery Anglican Archives - Montreal Diocese, Québec Diocese, Ottawa Diocese Presbyterian Archives – Toronto Creuzbourg's Jäger Corps From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Creuzbourg's Jäger Corps (Jäger-Corps von Creuzbourg) was an independent Jäger battalion raised by thecounty of Hesse-Hanau and put to the disposition of the British Crown, as part of the German Allied contingent during the American Revolutionary War. The corps fought at the Battle of Oriskany, although mostly serving as garrison of different Canadian posts. 2 After the Treaty of Paris 1783 the Hesse-Hanau contingent was repatriated. -

Fall Program September to December 2018

FALL PROGRAM SEPTEMBER TO DECEMBER 2018 Our professional counsellors are here to listen as you explain your situation and to guide you toward services and resources in your community. Contact us! Artwork by Marie-Françoise M. created during the Society’s art therapy workshops for people with dementia CONTENTS Alzheimer Society of Montreal SERVICES FOR CAREGIVERS ............................. 2 Alzheimer Service Centre SERVICES FOR PEOPLE LIVING WITH DEMENTIA ........... 10 4505 Notre-Dame Street West, Montréal SERVICES FOR PEOPLE LIVING WITH DEMENTIA 514-369-0800 | [email protected] AND THEIR CAREGIVERS ................................ 12 SERVICES FOR PROFESSIONALS AND ORGANIZATIONS ..... 14 Opening hours: SERVICES FOR ALL — ALZHEIMER CAFÉ .................. 17 Monday to Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. SERVICES POURFOR CAREGIVERS PROCHES AIDANTS THE COUNSELLING- NETWORK Chalet Coolbrooke, DDO Do you have a friend or family member living with Alzheimer’s 260 Spring Garden Street disease or a related form of dementia? Would you like to talk about your situation and the challenges you are facing? Do you need support and want to know where you can find it? Our counsellors are available to meet caregivers at the following locations to offer accompaniment, free and confidential counselling, training, information, resources, and support. Carrefour des 6–12 ans de Pierrefonds-Est inc. To discuss your situation or make 4773 Lalande Boulevard an appointment: 514-369-0800 [email protected] Foyer Dorval 225 de la Présentation Avenue 2 FALL -

Montréal for Groups Contents

MONTRÉAL FOR GROUPS CONTENTS RESTAURANTS ...........................................2 TOURIST ATTRACTIONS ............................17 ACTIVITIES AND ENTERTAINMENT ............43 CHARTERED BUS SERVICES .......................61 GUIDED TOURS ...........................................63 PERFORMANCE VENUES ............................73 CONTACT ...................................................83 RESTAURANTS RESTAURANTS TOURISME MONTRÉAL RESTAURANTS THE FOLLOWING RESTAURANTS WELCOME GROUPS. To view additional restaurants that suit your needs, please refer to our website: www.tourisme-montreal.org/Cuisine/restaurants FRANCE ESPACE LA FONTAINE 3933 du Parc-La Fontaine Avenue Plateau Mont-Royal and Mile End Suzanne Vadnais 514 280-2525 Tel.: 514 280-2525 ÇSherbrooke Email: [email protected] www.espacelafontaine.com In a pleasant family atmosphere, the cultural bistro Espace La Fontaine, in the heart of Parc La Fontaine, offers healthy, affordable meals prepared with quality products by chef Bernard Beaudoin. Featured: smoked salmon, tartar, catch of the day, bavette. The brunch menu is served on weekends to satisfy breakfast enthusiasts: pancakes, eggs benedict. Possibility of using a catering service in addition to a rental space for groups of 25 people or more. Within this enchanting framework, Espace La Fontaine offers temporary exhibitions of renowned artists: visual arts, photographs, books, arts and crafts, and cultural programming for the general public. Open: open year round. Consult the schedule on the Espace La Fontaine website. Reservations required for groups of 25 or more. Services • menu for groups • breakfast and brunch • terrace • dinner show • off the grill • gluten free • specialty: desserts • specialty: vegetarian dishes • Wifi LE BOURLINGUEUR 363 Saint-François-Xavier Street Old Montréal and Old Port 514 845-3646 ÇPlace-d’Armes www.lebourlingueur.ca Close to the St. Lawrence River is Le Bourlingueur with its menu of seafood specialties, in particular poached salmon. -

Immediate Occupancy 33 Exceptional Projects Find More Projects At

SUMMER 2015 CONDO COLLECTION immediate occupancy 33 exceptional projects find more projects at www.mcgillrealestate.com REAL ESTATE GRIFFINTOWN only a couple of models still available. REAL ESTATE Condo distriCt Griffin neiGhbor of the bassins du havre, faCinG the water, * to make an appointment: amazinG real estate projeCt in Griffintown, Close to the university. 2 br (1170 sQ.ft.) starting from $411,500 natalia blanchette Your condo at District Griffin sur Peel will allow you to access a wide range of services : grocery store, pharmacy, SAQ, financial institutions * Plus taxes. [email protected] and several restaurants and boutiques. Condos & Penthouses of 1, 2 & 3 bedrooms. Roof terrace with 360º views, spectacular and abundant 514.804.7720 windows, balconies, high quality kitchen cabinets, lockers, garages, design and upscale finishes at unbeatable prices. sales office: anika QuicQuaRo A rapidly transforming neighborhood conveniently located between Old Montreal, downtown, the Atwater Market and the Lachine Canal. The 1040 wellington st., montreal (Quebec) h3C 0m1 anika mcgillrealestate.com numerous galleries, art centers, restaurants and terraces bring new life to the city. @ phone: 514.914.4743 514.559.6886 Don’t miss your chance to invest in a development that’s right in the heart of an area in full expansion. To top it all off, the prices are unbeatable. villeray numeRous seRvices and amenities. Castelnau phase 2 is a ConCrete ConstruCtion with an eleGant arChiteCture starting from * that seamlessly inteGrates with the urban neiGhbourhood. 2 br (848 to 989 sQ. ft.) $319,500 REAL ESTATE penthouse (1338 sQ. ft.) starting from $609,999 * Located next to Jarry park, Little Italy and the Jean-Talon market, Castelnau’s Phase 2 offers a location close to many services, green spaces, restaurants, cafes and is very accessible by car and public transit. -

Griffintown: Developing Culture

Griffintown: Developing Culture Building community: an arts and heritage corridor in southwest Montreal http://corridorculturel.co/ [email protected] CORRIDOR CULTUREL We are actually powerfully influenced by our surroundings, our immediate context, and the personalities of those around us…. In the end, Tipping Points are a reaffirmation of the potential for change and the power of intelligent action. — Malcolm Gladwell, The Tipping Point — 2 http://corridorculturel.co/ [email protected] CORRIDOR CULTUREL Table of Contents Why:...............................................................................................................................................4 What:.............................................................................................................................................4 Where: ..........................................................................................................................................6 How:...............................................................................................................................................6 Some key sites & possibilities ..............................................................................................9 Griffintown Horse Palace.................................................................................................................9 Maison de la Culture ....................................................................................................................... 10 The New City -

Westmount Square”, Westmount “Heritatage”, Old Port

WESTMOUNT INDEPENDENT Weekly. Vol. 13 No. 3a We are Westmount March 5, 2019 Turcot work to close public Astronaut Thirsk visits Roslyn access to Public Works yard By Laureen Sweeney way and is presenting untold challenges to the Public Works operations, he said. The KPH-Turcot consortium building Information is hard to obtain from the the new Highway 136 at the foot of West- consortium, but at least one of the garages mount will be moving workers and ma- will be difficult to access. The city has work chinery into the city’s Public Works yard to do around the gas tanks and space for “tentatively” in mid-March, city director employees on the parking lot will be re- general Benoit Hurtubise announced last duced. week. This will close off public access to The area will also be “completely off the area for an unknown number of limits” to residents and contractors using months. the usual containers along the retaining “I wouldn’t say a year but several wall for dropping off recyclables, branch- months,” he said. “We don’t know how long.” es and dumping other material. “It’s a mat- The work involves rebuilding and pin- ter of safety,” Hurtubise said. ning up the retaining wall to the new high- As a result, people will be directed to use the two nearest eco-centres in Côte des Don’t Miss It Neiges and LaSalle. He said the city would find another lo- Wednesday, March 6 cation for its distribution of spring com- Héma-Québec Blood Drive. post to residents. -

1 Recensement De 1921, Index Des Rues – Montréal, Québec Rue

Recensement de 1921, index des rues – Montréal, Québec Rue / avenue / institution Numéro du district Numéro du sous-district Abbott 211 64 Aberdeen 211 61, 68 Adam 180 24, 25, 29, 30, 33, 34, 37, 38, 42, 43, 46, 47 Addington 169 1, 24, 31 Agnes 211 29, 30 Ahletic 175 61 Ainslie Avenue 169 50 Ainslie Avenue 175 58 Aird Avenue 180 28, 29, 30, 31 Albert 197 14 Albert 211 6, 7, 8, 9, 20, 21 Albert Place 211 74 Albina Avenue 211 24 Albina Avenue 175 61 Alboy 175 62 Alexander 197 42 Alexandra 169 28 Alexandra 175 44 Alexandra 198 41 Alfred 200 7 Allard 169 44 Allard 203 8 Allen Avenue 169 35, 36 Allen Place 169 33 Alma Avenue 175 37, 42, 43, 46, 48 Amesbury 197 21 Amherst 200 12, 13, 19, 22, 25, 26, 29, 30, 32, 33, 35 Amity 203 65, 67, 71, 72 Anderson 202 7, 11 Angers 169 11, 12, 13 Anita 203 67 Ann Avenue 196 4 Annette Avenue 200 32 Anoteau 198 46, 48, 58 Anvers Avenue 169 1, 35 Apple 175 61 Aqueduct 196 13 Aqueduct 197 4, 17, 23 Arcade 202 49, 50 Archambault 203 50, 51 Argyle 197 22 1 Rue / avenue / institution Numéro du district Numéro du sous-district Argyle Avenue 196 69 Argyle Avenue 211 62, 68 Arlington Avenue 211 67 Armand 180 51 Arthur 167 3 Ash Avenue 196 25, 40, 41 Athol Place 169 33 Atlantic Avenue 175 33, 38, 45 Atwater 197 45 Atwater Avenue 169 1 Atwater Avenue 211 1, 2, 3, 7, 8, 10, 13, 18, 20, 22, 23, 52, 58 Aubut 197 16 Audette 198 6 Avenue Road 211 61 Avonmore Avenue 169 32 Aylmer 202 66, 67 Aylwin 167 4, 6, 7, 10, 11, 14, 17, 18 Ayr 180 58 Azilda 180 9, 12 Baby 175 44, 47 Baby 198 41 Bagg 166 2, 3 Bagg 202 48, 51, 52 Baldwin -

Things to See in Montreal

Things to see in Montreal: Notre-Dame Basilica: https://www.basiliquenotredame.ca/en Montreal Botanical Garden: http://espacepourlavie.ca/en/botanical-garden Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montréal: https://www.mbam.qc.ca/en/ Mount-Royal Park: Within easy walking distance from McGill. The "interactive map" is especially useful: http://www.lemontroyal.qc.ca/en/learn-about-mount-royal/homepage.sn Old Montreal/ Old Port: http://www.vieux.montreal.qc.ca/eng/accueila.htm Montreal Biodome: http://espacepourlavie.ca/en/biodome Saint Laurent Boulevard A commercial and cultural street that runs north to south through the city center Free Montreal Tours and Montreal Food Tours: www.freemontrealtours.com Saint Helen’s Island An island located in the Saint Lawrence river, home to a beautiful park, beach, formula one course, amusement park, casino and wonderful historical buildings. Underground City Montreal has an Underground City, which is a series of interconnected tunnels beneath the city that run for over 32km. The tunnels connect shopping malls, over 2000 stores, 7 metro stations,universities, banks, offices, museums, restaurants. https://montrealundergroundcity.com/ Jean-Talon Market A famous open-air market with speciality vendors selling local produce, meats, cheese,fish and speciality goods. https://www.marchespublics-mtl.com/en/marches/jean-talon-market/ Atwater Market Located beside Canada Parks “Lachine Canal”, the Atwater Market is an open air market that offers local produce, meats, cheese,fish and speciality goods. https://www.marchespublics-mtl.com/en/marches/atwater-market/ Hotels: AirBnb: AirBnB offers you somebody’s home as a place to stay in Montreal. You may choose this option instead of a hotel at your own discretion. -

Greene Avenue Detail of Painting Depicting the Tollgate at East Entrance to the Village of Côte St

The Westmount Historian NEWSLETTER OF THE WESTMOUNT HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION VOLUME 12 NUMBER 1 SEPTEMBER 2011 Greene Avenue Detail of painting depicting the tollgate at east entrance to the Village of Côte St. Antoine (1879-1890), which became Westmount in 1895. Greene Avenue was named on May 5, 1884. The Westmount Historian PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE NEWSLETTER OF THE WESTMOUNT n Westmount, history is everywhere. You walk down a HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION Istreet and ask yourself how did it start? Who named it? When and why? In this September issue of our newsletter September 2011 we explore Greene Avenue, which became Westmount’s Volume 12 • Number 1 first commercial centre. Every business and every street number has its story to tell. You will find maps and an ex- EDITOR: Doreen Lindsay planation of how the Grey Nuns (Les Sœurs Grise de Mon- tréal) acquired the entire west side of Greene Avenue CONTRIBUTORS: between Ste. Catherine and Sherbrooke Streets by 1858, how Doreen Lindsay Marie-Andrée Cantillon they used this property and to whom they eventually sold. Amongst the antique shops, jewellers, fashion designers, realtors, phar macies, Photos: WHA Archives unless otherwise indicated bookstores, health stores, and children’s stores two elements that have pre- dominated over the years are art galleries and restaurants. The West End Art Gallery was opened on the Avenue in 1964 by Florence WESTMOUNT HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION Millman, and is continued today by her son Michael Millman. BOARD OF DIRECTORS Westmounters have enjoyed many fine restaurants on Greene over the years. 2011 – 2012 The recent change of ownership of Bistro On The Avenue leads to the continu- Doreen Lindsay, president Caroline Breslaw, vice-president ation of this twenty-year-old French style restaurant that opened in 1991.