Downtown Montreal and Toronto: Distinct Places with Much in Common

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St. Matthias' Anglican Church

St.Matthias? Anglican Church The nave, looking toward the choir Photo: Bergeron Gagnon inc. Photo: Bergeron Gagnon inc. THE VALUE STATEMENT ST. MATTHIAS' ANGLICAN CHURCH CIVIC ADDRESS HERITAGE DESIGNATION RELIGIOUS DENOMINATION 10 Church Hill, Westmount Municipal - Category 1: Important Anglican (SPAIP) Provincial - None Federal - None OVERVIEW OF THE VALUE STATEMENT Historical Value The historical heritage value resides in the long history of the St. Matthias? Anglican Church with the development of Westmount. Its site has been continuously occupied by this religious denomination since 1874, when a mission chapel was established on a portion of the Forden Estate. The present church dates from 1912 and the parish hall from 1936. The association of the church with its immediate neighbourhood is embedded in the name chosen for the adjacent street, Church Hill. The sacrifice of the church membership during both World Wars is commemorated in the Memorial Chapel. Contextual Value The contextual heritage value resides in the church?s commanding presence on the corner of Cote St. Antoine and Church Hill. At the same time, the multiple entrances allow the complex to be easily accessed from both streets. Its institutional size and character make it a landmark within the surrounding residential fabric and connects it as well to the neighbouring institutions. Although its site is now almost entirely built up, the remaining church land is densely planted with shrubbery and mature trees. Architectural and Aesthetic Value The architectural and aesthetic heritage value resides in the skilful rendering of the neo-Gothic style, the excellent functional design, the ornamentation enhanced by the complex massing, the craftsmanship and the simple, noble materials used throughout both the exterior and interior of the complex. -

Spring Office Market Report 2018 Greater Montreal

SPRING OFFICE MARKET REPORT 2018 GREATER MONTREAL Image Credit: Avison Young Québec Inc. PAGE 1 SPRING 2018 OFFICE MARKET REPORT | GREATER MONTREAL SPRING OFFICE MARKET REPORT 2018 GREATER MONTREAL Office market conditions have Class-A availability Downtown been very stable in the Greater Montreal reached 11.7% at the Montreal Area (GMA) over the end of the first quarter, which past year, but recent news lead represents an increase of only 20 to believe this could change basis points year-over-year. drastically over the years to come as major projects were announced Landlords who invested in their and the construction of Montreal’s properties and repositioned their Réseau Express Métropolitain assets in Downtown Montreal over (REM) began. New projects and the past years are benefiting from future developments are expected their investments as their portfolios to shake up Montreal’s real estate show more stability and success markets and put a dent in the than most. stability observed over the past quarters. It is the case at Place Ville Marie, where Ivanhoé Cambridge is Even with a positive absorption of attracting new tenants who nearly 954,000 square feet (sf) of are typically not interested in space over the last 12 months, the traditional office space Downtown total office availability in the GMA Montreal, such as Sid Lee, who will remained relatively unchanged be occupying the former banking year-over-year with the delivery of halls previously occupied by the new inventory, reaching 14.6% at Royal Bank of Canada. Vacancy and the end of the first quarter of 2018 availability in the iconic complex from 14.5% the previous year. -

A Living History of Montreal's Early Jewish Community

A NEW LIFE FOR CANADIANA VILLAGE? $5 Quebec HeritageVOL 3, NO. 12 NOV-DEC. 2006 News The Bagg Shul A living history of Montreal’s early Jewish community The Street that Roared Why the fight to save Montreal milestone matters to Mile Enders Christbaum comes to Canada Decorated tree topped pudding at Sorel party Quebec CONTENT HeritageNews EDITOR President’s Message 3 CHARLES BURY School Spirit Rod MacLeod DESIGN DAN PINESE Letters 5 Opinion 6 PUBLISHER Wisdom of the rubber stamps Jim Wilson THE QUEBEC ANGLOPHONE HERITAGE NETWORK TimeLines 7 400-257 QUEEN STREET SHERBROOKE (LENNOXVILLE) One stop culture shop QUEBEC Taste of the world J1M 1K7 The unknown settlers PHONE A philanthropist’s legacy 1-877-964-0409 New owner, same purpose for Saguenay church (819) 564-9595 Canadiana Village changes hands FAX Tombstone rising 564-6872 C ORRESPONDENCE The Street that Roared 14 [email protected] Why the fight for Montreal milestone matters Carolyn Shaffer WEBSITE The Bagg Shul 17 WWW.QAHN.ORG Montreal’s early Jewish community Carolyn Shaffer Christbaum Comes to Canada 19 PRESIDENT Decorated tree topped pudding at Sorel party RODERICK MACLEOD Bridge to Suburbia 21 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Vanished English towns and the South Shore’s past Kevin Erskine-Henry DWANE WILKIN What’s in a Name? 22 HERITAGE PORTAL COORDINATOR Land of shrugs and strangers Joseph Graham MATHEW FARFAN OFFICE MANAGER Book Reviews 24 KATHY TEASDALE Adventism in Quebec The Eastern Townships Quebec Heritage Magazine is Cyclone Days produced on a bi-monthly basis by the Quebec Anglophone Heritage Network (QAHN) with the support of The HindSight 26 Department of Canadian Heritage and Quebec’s Ministere de la Culture et des Luck of the potted frog Joseph Graham Communications. -

Cahiers De Géographie Du Québec

Document généré le 24 sept. 2021 23:27 Cahiers de géographie du Québec Le nouveau centre-ville de Montréal Clément Demers Volume 27, numéro 71, 1983 Résumé de l'article Le centre-ville de Montréal vient de connaître un boom immobilier qui n'a URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/021609ar d'égal que celui des années 1960-62. Cette activité fébrile sera suivie d'un DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/021609ar inévitable ralentissement, puis d'une éventuelle reprise. Les bâtiments publics et privés qui viennent d'être construits ont en quelque sorte refaçonné Aller au sommaire du numéro certaines parties du quartier. Cette transformation s'inscrit dans le prolongement du développement des décennies précédentes, bien qu'elle présente certaines particularités à divers points de vue. Le présent article Éditeur(s) effectue l'analyse de cette récente relance et propose certaines réflexions sur l'avenir du centre-ville de Montréal. Département de géographie de l'Université Laval ISSN 0007-9766 (imprimé) 1708-8968 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Demers, C. (1983). Le nouveau centre-ville de Montréal. Cahiers de géographie du Québec, 27(71), 209–235. https://doi.org/10.7202/021609ar Tous droits réservés © Cahiers de géographie du Québec, 1983 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. -

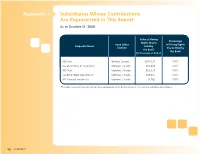

Subsidiaries Whose Contributions Are Represented in This Report As at October 31, 2009

Appendix 1 Subsidiaries Whose Contributions Are Represented In This Report As at October 31, 2009 Value of Voting Percentage Rights Shares Head Office of Voting Rights Corporate Name Held by Location Shares Held by the Bank1 the Bank (In thousands of dollars) B2B Trust Toronto, Canada $286,530 100% Laurentian Trust of Canada Inc. Montreal, Canada $85,409 100% LBC Trust Montreal, Canada $62,074 100% Laurentian Bank Securities Inc. Montreal, Canada $39,307 100% LBC Financial Services Inc. Montreal, Canada $4,763 100% 1 The book value of shares with voting rights corresponds to the Bank’s interest in the equity of subsidiary shareholders. 23 APPENDIX Appendix 2 Employee Population by Province and Status As at October 31, 2009 Province Full-Time Part-Time Temporary Total Alberta 10 – – 10 British Columbia 6 – – 6 Newfoundland 1 – – 1 Nova Scotia 1 – – 1 Ontario 369 4 81 454 Québec 2,513 617 275 3,405 TOTAL 2,900 621 356 3,877 24 APPENDIX Appendix 3 Financing by commercial client loan – Amounts authorized during the year As at October 31, 2009 0 − 25,000 − 100,000 − 250,000 − 500,000 − 1,000,000 − 5,000,000 Province Total 24,999 99,999 249,999 499,999 999,999 4,999,999 and over British Columbia Authorized amount 168,993 168,993 Number of clients 1 1 New Brunswick Authorized amount Number of clients Ontario Authorized amount 151,900 1,024,068 3,108,000 8,718,154 30,347,394 189,266,928 296,349,931 528,966,375 Number of clients 16 18 20 26 43 90 29 242 Québec Authorized amount 16,050,180 92,265,280 172,437,714 229,601,369 267,927,253 689,934,205 -

Review Market Report 2017 Greater Montreal Area

YEAR-END OFFICE REVIEW MARKET REPORT 2017 GREATER MONTREAL AREA PAGE 1 2017 YEAR-END REVIEW OFFICE MARKET REPORT | GREATER MONTREAL YEAR-END OFFICE REVIEW MARKET REPORT 2017 GREATER MONTREAL AREA 2017 proved to be a very successful 15.5% to 14.7%. The GMA’s vacancy year for the Greater Montreal Area, rate is expected to tick back up as the Province’s unemployment over the next months, as many rates dropped to unprecedented mixed-use and office projects are lows and the city’s economy currently under construction on thrived in numerous activity and off-island. sectors. Artificial intelligence (AI) stole the spotlight last year, as Overall, the average net rental rates Montreal is becoming a growing in the GMA remained relatively hub for AI. The city is now home unchanged over the past year, to AI research laboratories from hovering around $14.00 per square Microsoft, Facebook, Google, foot (psf) for all office classes, while Samsung and Thales, and local- the additional rates remained in based AI players such as Element the vicinity of $13.00 psf. However, AI keep on expanding at a the gap between rental rates in drastic pace. The metropolitan the Downtown core and the other area maintained the sustained submarkets remains significant, as economic growth witnessed over net rental rates in the central areas the past years in 2017, leaning are closer to $17.00 psf and the towards an optimistic outlook for additional rents are approaching the years to come. $18.00 psf. From an office market perspective, The demand for quality office there has been a healthy decrease space in the Downtown Core is in available space, slightly shifting improving. -

Integrating Transportation and Land Use Planning at the Metropolitan Level in North America 185

Integrating transportation and land use planning at the metropolitan level in North America: multilevel governance in Toronto and Chicago Integrando o planejamento de transporte e de uso do solo em escala metropolitana na América do Norte: governança multinível em Toronto e Chicago Fanny R. Tremblay-Racicot[a], Jean Mercier[b] Licenciado sob uma Licença Creative Commons DOI: 10.7213/urbe.06.002.SE04 ISSN 2175-3369 [a] Ph.D candidate in Urban Studies at Department of Geography and Urban Studies, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA - United States, e-mail: [email protected] [b] Ph.D in public administration (SU), professor at Université Laval, Québec, QC - Canada, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article compares the policies and processes by which transportation and land use planning are integra- ted in metropolitan Toronto, Canada, and Chicago, in the United States. Using twenty-four semi-structured interviews with key informants, it describes the array of interventions undertaken by governmental and non-governmental actors in their respective domains to shed light on how the challenge of integrating trans- portation and land use planning is addressed on both sides of the border. Evidence concerning the political dynamics in Toronto and Chicago demonstrates that the capacity of metropolitan institutions to adopt and implement plans that integrate transportation with land use fundamentally depends on the leadership of the province or the state government. Although the federal government of each nation can bypass the sub-national level and intervene in local affairs by funding transportation projects that include land use components, its capacity to promote a coherent metropolitan vision is inherently limited. -

Toronto Police Service Community Consultation and Volunteer Manual

1 November 2019 2 Volunteers and Community Policing The Toronto Police Service (Service) recognizes that volunteers are an integral and vital component of community policing. Service volunteers are welcomed and valued in every community, and their service to the organization is invaluable. Our volunteers serve as the first point of contact between the community and the Service. They make an impact and strengthen ties in our communities, they serve to enhance the delivery of police services, and assist in numerous community engagement initiatives and programs. The Mission Statement of the Toronto Police Service Volunteer Program is; “To create meaningful partnerships through trust, understanding, shared knowledge, effective community engagement and to maintain safety and security in our communities.” Connected by Commitment Revised November 2020 2 3 MESSAGE FROM THE TORONTO POLICE SERVICES BOARD On behalf of the Toronto Police Services Board, I would like to extend our deep and sincere appreciation to all of our volunteers for giving your time, energy, and dedication to the Toronto Police Service and to all of the communities that make up the City of Toronto. The Toronto Police Service is recognized as outstanding model in the policing community in the way in which it consults with its communities. The Board is extremely proud of this achievement and is committed to continuously working to ensure that we remain a progressive leader in this vital area. Strong and meaningful partnership with the community is an essential component of the Board’s emphasis on community policing. Indeed, The Way Forward, the Transformational Task Force’s action plan report, charts an approach to policing that is founded on embracing partnerships to create safe communities. -

Rapid Transit in Toronto Levyrapidtransit.Ca TABLE of CONTENTS

The Neptis Foundation has collaborated with Edward J. Levy to publish this history of rapid transit proposals for the City of Toronto. Given Neptis’s focus on regional issues, we have supported Levy’s work because it demon- strates clearly that regional rapid transit cannot function eff ectively without a well-designed network at the core of the region. Toronto does not yet have such a network, as you will discover through the maps and historical photographs in this interactive web-book. We hope the material will contribute to ongoing debates on the need to create such a network. This web-book would not been produced without the vital eff orts of Philippa Campsie and Brent Gilliard, who have worked with Mr. Levy over two years to organize, edit, and present the volumes of text and illustrations. 1 Rapid Transit in Toronto levyrapidtransit.ca TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 INTRODUCTION 7 About this Book 9 Edward J. Levy 11 A Note from the Neptis Foundation 13 Author’s Note 16 Author’s Guiding Principle: The Need for a Network 18 Executive Summary 24 PART ONE: EARLY PLANNING FOR RAPID TRANSIT 1909 – 1945 CHAPTER 1: THE BEGINNING OF RAPID TRANSIT PLANNING IN TORONTO 25 1.0 Summary 26 1.1 The Story Begins 29 1.2 The First Subway Proposal 32 1.3 The Jacobs & Davies Report: Prescient but Premature 34 1.4 Putting the Proposal in Context CHAPTER 2: “The Rapid Transit System of the Future” and a Look Ahead, 1911 – 1913 36 2.0 Summary 37 2.1 The Evolving Vision, 1911 40 2.2 The Arnold Report: The Subway Alternative, 1912 44 2.3 Crossing the Valley CHAPTER 3: R.C. -

MONTREAL to WELCOME a NEW CITY MUSEUM Major Benefactor Donates $15 Million

MONTREAL TO WELCOME A NEW CITY MUSEUM Major benefactor donates $15 million Montreal, April 30, 2019 - The McCord Stewart Museum is proud to announce that its planned new museum will be located in the heart of downtown Montreal. The new establishment will expand the McCord Museum’s current site by building on Victoria Street, which runs along the west side of the Museum, and the lot housing the former Caveau restaurant on President Kennedy Avenue. The combined area of these sites will enable the museum to meet its needs for additional space and create an institution that will leave its mark on Montreal’s urban and cultural landscape. Working closely with the City of Montreal, which is granting the right to build on Victoria Street, the Museum selected the site after conducting a feasibility study. The new building will house three recently merged museums—the McCord Museum, the Stewart Museum and the Fashion Museum—under a single roof. This legacy project will create a world-class institution for generations of Montrealers. «Our administration believes that it is important to build this new museum. It will be a major attraction for our city and a source of pride for all Montrealers. We are pleased to be able to help advance the project by granting the right to use Victoria Street, so that this cultural space may continue to attract visitors, both locals and tourists, in the heart of the city’s downtown museum district,» declared Montreal Mayor Valérie Plante. New museum to receive historic donation The McCord Stewart Museum also announced that La Fondation Emmanuelle Gattuso had pledged to donate the extraordinary sum of $15 million towards the project. -

The Churches of the Europeans in Québec

The Europeans in Québec Lower Canada and Québec The Churches of the Europeans in Québec Compiled by Jacques Gagné - [email protected] Updated: April 2012 The Europeans in Québec Lower Canada and Québec The Churches of the Europeans in Québec Churches of the Scandinavian, Baltic States, Germanic, Icelandic people in Montréal, Québec City, Lower St. Lawrence, Western Québec, Eastern Townships, Richelieu River Valley - The churches of immigrants from Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland, Estonia, Latvia. Lithuania, Iceland, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, Switzerland, Austria plus those from Eastern European countries - Churches which were organized in Québec from 1621 to 2005. Also included within this document you will find a number of book titles relating to the subject. Major Repositories quoted within this compilation QFHS - Quebec Family History Society in Pointe Claire BAnQ - Bibliothèque Archives nationales du Québec in Montréal Ancestry.ca - The Canadian division of Ancestry.com Lutheran Church-Canada - East District Conference Lutheran Church-Canada - Montreal Lutheran Council United Church of Canada Archives- Montreal & Ottawa Conference United Church of Canada Archives - Montreal Presbytery Anglican Archives - Montreal Diocese, Québec Diocese, Ottawa Diocese Presbyterian Archives – Toronto Creuzbourg's Jäger Corps From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Creuzbourg's Jäger Corps (Jäger-Corps von Creuzbourg) was an independent Jäger battalion raised by thecounty of Hesse-Hanau and put to the disposition of the British Crown, as part of the German Allied contingent during the American Revolutionary War. The corps fought at the Battle of Oriskany, although mostly serving as garrison of different Canadian posts. 2 After the Treaty of Paris 1783 the Hesse-Hanau contingent was repatriated. -

Visions of Canada: Photographs and History in a Museum, 1921-1967

Visions of Canada: Photographs and History in a Museum, 1921-1967 Heather McNabb A Thesis In the Department of History Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada May 2015 © Heather McNabb 2015 ii iii ABSTRACT Visions of Canada: Photographs and History in a Museum, 1921-1967 Heather McNabb, PhD. Concordia University, 2015 This dissertation is an exploration of the changing role of photographs used in the dissemination of history by a twentieth-century Canadian history museum. Based on archival research, the study focuses on some of the changes that occurred in museum practice over four and a half decades at Montreal’s McCord Museum. The McCord was in many ways typical of other small history museums of its time, and this work illuminates some of the transformations undergone by other similar organizations in an era of professionalization of many fields, including those of academic and public history. Much has been written in recent scholarly literature on the subject of photographs and the past. Many of these works, however, have tended to examine the original context in which the photographic material was taken, as well as its initial use(s). Instead, this study takes as its starting point the way in which historic photographs were employed over time, after they had arrived within the space of the museum. Archival research for this dissertation suggests that photographs, initially considered useful primarily for reference purposes at the McCord Museum in the early twentieth century, gradually gained acceptance as historical objects to be exhibited in their own right, depicting specific moments from the past to visitors.