Cycles of Conflict, Displacement and Abuse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yemen's National Dialogue

arab uprisings Yemen’s National Dialogue March 21, 2013 MOHAMMED HUWAIS/AFP/GETTY IMAGES HUWAIS/AFP/GETTY MOHAMMED POMEPS Briefings 19 Contents Overcoming the Pitfalls of Yemen’s National Dialogue . 5 Consolidating Uncertainty in Yemen . 7 Can Yemen be a Nation United? . 10 Yemen’s Southern Intifada . 13 Best Friends Forever for Yemen’s Revolutionaries? . 18 A Shake Up in Yemen’s GPC? . 21 Hot Pants: A Visit to Ousted Yemeni Leader Ali Abdullah Saleh’s New Presidential Museum . .. 23 Triage for a fracturing Yemen . 26 Building a Yemeni state while losing a nation . 32 Yemen’s Rocky Roadmap . 35 Don’t call Yemen a “failed state” . 38 The Project on Middle East Political Science The Project on Middle East Political Science (POMEPS) is a collaborative network which aims to increase the impact of political scientists specializing in the study of the Middle East in the public sphere and in the academic community . POMEPS, directed by Marc Lynch, is based at the Institute for Middle East Studies at the George Washington University and is supported by the Carnegie Corporation and the Social Science Research Council . It is a co-sponsor of the Middle East Channel (http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com) . For more information, see http://www .pomeps .org . Online Article Index Overcoming the Pitfalls of Yemen’s National Dialogue http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com/posts/2013/03/18/overcoming_the_pitfalls_of_yemen_s_national_dialogue Consolidating Uncertainty in Yemen http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com/posts/2013/02/22/consolidating_uncertainty_in_yemen -

Report on the Nutritional Situation and Mortality Survey Al Jawf

Republic of Yemen Ministry of Public Health and Population Central Statistical Organization Report on the Nutritional Situation and Mortality Survey Al Jawf Governorate, Yemen From 19 to 25 April 2018 1 Acknowledgment The Ministry of Public Health and Population in Yemen, represented by the Public Health and Population Office in the Al Jawf governorate and in cooperation with the UNICEF country office in Yemen and the UNICEF branch in Sana’a, acknowledges the contribution of different stakeholders in this survey. The UNICEF country office in Yemen provided technical support, using the SMART methodology, while the survey manager and his assistants from the Ministry of Public Health and Population and the Public Health and Population Offices in Amran and Taiz were also relied on. The surveyors and team heads were provided by the Public Health and Population Office in the Al Jawf governorate. The data entry team was provided by the Public Health and Population Office in Amran and the Nutrition Department in the Ministry. The survey protocol was prepared, and other changes were made to it, through cooperation between the Ministry of Public Health and Population and the Central Statistical Organization, with technical support from UNICEF. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development provided UNICEF with technical assistance, especially with regards to daily quality checks, data analysis, and report writing. The Building Foundation for Development provided technical and logistical support through extensive coordination with the local authorities in the Al Jawf governorate, as well as through their choice of the survey team and providing extensive training for them. The Building Foundation for Development was also responsible for regular follow-up with the survey teams out in the field and providing logistical and technical support for these teams, as well as preparing the initial draft of the survey report. -

0 Desk Study

DESK STUDY Multidimensional Livelihoods Assessment in Conflict-Affected Areas 0 Contents Executive summary ............................................................................................................... 3 I. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 7 1. Background ....................................................................................................................................... 7 2. Objectives.......................................................................................................................................... 8 3. Methodology ..................................................................................................................................... 8 II. Population .................................................................................................................. 8 III. Poverty ....................................................................................................................... 9 IV. Structure of the Yemen economy .............................................................................. 11 V. Impact of the 2011 crisis on employment, skilled and unskilled labour, and the private sector ........................................................................................................................ 12 VI. Main livelihood activities and the impact of conflict on selected sectors .................... 14 A. Main livelihood activities ............................................................................................................... -

Humanitarian Update

HUMANITARIAN UPDATE Issue 02 / February 2020 Credit: BBC/ Lyse Doucet Medical airbridge launched On 3 February, a group of six In a joint statement, senior UN HIGHLIGHTS chronically ill children and their officials indicated that, “Many carers were flown from Sana’a to United Nations entities and several Medical airbridge launched Amman, Jordan for treatment; governments in the region and P 01 a second plane carrying 23 sick around the world have collaborated men, women and children and to get these patients the treatment UN calls for protection of their companions followed on 8 they need abroad, and we are civilians as war casualties February. The flights are part of grateful to them all. The United spike in Marib, Al Jawf and a United Nations/World Health Nations will do what it can to Sana’a governorates Organization (WHO) medical ensure the continuation of the P 02 airbridge operation transporting medical airbridge as a temporary chronically ill Yemenis who cannot solution to reduce the suffering of Humanitarian community get the treatment they need within the Yemeni people until a more reaffirms commitment to country . Many suffer from different sustainable solution is reached in the Yemen amid concerns on types of cancers, kidney disease, near future.” shrinking operating space congenital anomalies and other Patients for the flights were selected conditions that require specialist P 03 based on need, and their medical treatment. Aid agencies brace to files were reviewed by the High contain cholera ahead of the The launch of the operation was Medical Committee, a group of rainy season welcomed in a joint statement by medical doctors that work with senior UN leadership in Yemen, local health authorities to guide the P 04 including UN Special Envoy, selection process, and by a global YHF allocates a record Mr. -

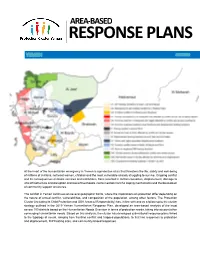

Area‐Based Response Plans

AREA‐BASED RESPONSE PLANS At the heart of the humanitarian emergency in Yemen is a protection crisis that threatens the life, safety and well-being of millions of civilians, not least women, children and the most vulnerable already struggling to survive. Ongoing conflict and its consequences on basic services and institutions, have resulted in civilian casualties, displacement, damage to vital infrastructure and disruption and loss of livelihoods, not to mention harmful coping mechanisms and the breakdown of community support structures. The conflict in Yemen continues on several geographic fronts, where the implications on protection differ depending on the nature of armed conflict, vulnerabilities, and composition of the population, among other factors. The Protection Cluster (including its Child Protection and GBV Areas of Responsibility) has, in line with and as a follow-up to the cluster strategy outlined in the 2019 Yemen Humanitarian Response Plan, developed an area-based analysis of the most severe 100 districts based on the Humanitarian Needs Overview in terms of protection needs, taking into account other converging humanitarian needs. Based on this analysis, the cluster has developed sub-national response plans linked to the typology of needs, ranging from frontline conflict and trapped populations, to first line responses to protection and displacement, IDP hosting sites, and community-based responses. OVERVIEW OF AREA‐BASED ANALYSIS Protection Situation Districts Population IDP IDP RET HNO (2018 HNO) (2018) (2019) Severity Hudaydah Hub H1. Civilians in al-Hudaydah City affected by conflict & risk of being trapped 3 176,344 13,512 1,662 15,384 4.89 H2. Frontline districts in Hudaydah & Hajjah affected by conflict & access 11 1,061,585 178,710 10,590 8,202 4.48 H3. -

YEMEN | Displacement in Marib, Sana'a and Al Jawf

YEMEN | Displacement in Marib, Sana’a and Al Jawf governorates Situation Report No. 1 2 February 2020 This report is produced by OCHA Yemen in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It covers the period from 19 January to 2 February 2020 HIGHLIGHTS • Between 19 January and 2 February, humanitarian partners report that 3,825 families were displaced in Nihm District in Sana’a Governorate, Sirwah District in Marib Governorate and Al Maton in Al Jawf Governorate, following a rapid escalation of hostilities. With many internally displaced families scattered across three governorates, in hard-to- reach areas, or seeking shelter with host communities, the total number of people displaced is likely to be higher than reported. • On 26 January, artillery shelling hit Al- Khaniq IDP site in Majzar District. No casualties were reported, however, most IDPs who were staying in the camp or in the vicinity, around 1,550 families, left for Medghal District or Marib City. • As of 28 January, some 2,000 families (including from Khaniq IDP site) have been displaced within Marib Governorate, around 500 families were displaced within Nihm District in Sana’a Governorate, and 400 families were displaced within Al Jawf Governorate. In addition, partners in Sana’a Governorate registered and provided immediate life-saving support through the Rapid Response Mechanism (RRM) to 180 displaced families in Bani Hushaysh District. • On 29 January, another 100 families were displaced from Sirwah District in Marib Governorate to Khawlan District in Sana’a Governorate. • Many of those fleeing frontline areas are being displaced for the second time and have exhausted their social or financial assets. -

10 August 2018 Excellency, I Have the Honour to Address You in My

PALAIS DES NATIONS • 1211 GENEVA 10, SWITZERLAND Mandate of the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions REFERENCE: AL SAU 10/2018 10 August 2018 Excellency, I have the honour to address you in my capacity as Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution 35/15. In this connection, I would like to bring to the attention of your Excellency’s Government information that I have received on a series of airstrikes by Government of Saudi Arabia-led coalition forces carried out since November 2017 in civilian areas in Yemen, including on protected civilian objects, that have caused numerous deaths and serious injuries to civilians, including children . On 9 November 2015, my mandate addressed a similar communication to your Excellency’s Government (AL SAU 9/2015) concerning indiscriminate airstrikes by coalition forces in civilian areas, which lead to deaths and injuries of civilians in Yemen. I regret that thus far no response has been received to that communication and would be grateful for your prompt response. The information which I have received in recent months, and which is indicative and non-exhaustive, highlights the impact of coalition-led attacks on civilians and civilian objects in Yemen over the period November 2017 to June 2018. The allegations may be summarized as follows: On 1 November 2017, two airstrikes by the Saudi-led coalition hit the Al Layl market in the area of Olaf, in Sahaar district, Sa’adah province, killing 31 civilians, including six children, and wounding 24 others. On 2 November 2017, seven members of a farming family, including three children, were killed in a coalition airstrike on their home in Al Islan area in Baqim district, Sa’adah province. -

Yemen Protection Brief

Protec�on Cluster Yemen YEMEN PROTECTION BRIEF October 2020 Operational Context Oman For more than five years, Yemen has been locked in an unrelen�ng, high-intensity conflict that Saudi Arabia has triggered what the UN describes as the worst humanitarian crisis in the world; with 24.3 million people in need of humanitarian assistance and protec�on1. Since its escala�on in Sa’ada Al Maharah 2015, an es�mated 12,000 civilians have been killed2 and more than 3.6 million are es�mated Al Jawf to be forcibly displaced.3 Ac�ve ground hos�li�es, coupled by shelling and air strikes, o�en in Amran Hadramawt populated areas, con�nue to harm civilians and cause widespread damage to civilian homes Hajjah and infrastructure, including schools, hospitals, IDP sites and water and sanita�on facili�es. Sana’a City Explosive remnants of war persist to impede freedom of movement as well as to kill and injure Al Mahwit Ma'rib civilians. Al Hudaydah Sana’a Dhamar Shabwah Yemen is also a country prone to disasters, par�cularly hydrological hazards such as flash Raymah Country boundary flooding, which are causing death, displacement and destruc�on of property. It is es�mated Al Bayda Governorate boundary that, since January 2020, more than half a million people have been affected by floods and Ibb District boundary Ad Dali' heavy rains, including 300,000 in June, July and August, mostly in Marib, Taiz, Al Hudaydah, Abyan Hajjah, Aden, Lahj and Aden governorates4. Affected families have lost their homes, crops and Ta’iz Red Sea Red Arabian Sea personal belongings.5 Outbreaks of diseases including dengue fever and cholera have also Lahj Socotra contributed to the ongoing humanitarian crisis, with a severe impact on vulnerable groups. -

Situation Update, No. 21 28 - 31 May 2015

Situation Update, No. 21 28 - 31 May 2015 Information by Governorate Al –Jawf governorate Al-Salam and Development Association is monitoring the number of IDPs from different governorate to districts in the Al-Jawf governorate, in particular the Al-Hazm district. This district has also become a gathering point for Ethiopian and Somali migrants. Interviews were conducted and many meetings held with several migrants, including women and children. An initial number of 54 persons were identified as Ethiopian and Somali nationals. These persons reported that they had attempted to enter Saudi Arabia, but did not succeed owing to conflict at the border between Saudi Arabia and Yemen. They are currently living in extremely harsh conditions and are greatly in need of the most basic humanitarian assistance, including food and water. Some also indicated a wish to return to their countries of origin and are seeking assistance in this regard. Many are now sleeping on the sidewalks or in mosques, as they do not have adequate shelter and are surviving on charity. Information provided by these groups indicates that there are large numbers of migrants in a similar situations close to the border areas. The estimated number of migrants is as follows: Location Number Al-Hazm 54 Al-Muton 23 Khab Wa Al-Shaqf 48 Total 125 Amran On 29 May 2015, the Yemen Red Crescent Society (YRCS) distributed NFIs on behalf of UNHCR in Khamir district to 88 IDP families (452 individuals). In addition, mattresses were distributed 417 families (2,140 individuals). Ibb governorate The Humanitarian Forum Yemen (YHF) has received information from local authorities pertaining to the situation of displacement in the Ibb governorate. -

Com Mplex Em Mergency Y

BUREAU FOR DEMOCRACY, CONFLICT, AND HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE (DCHA) OFFICE OF U.S. FOREIGN DISASTER ASSISTANCE (OFDA) Yemen – Complex Emergency Fact Sheet #4, Fiscal Year (FY) 2011 June 15, 2011 Note: The last fact sheet was dated April 28, 2011. KEY DEVELOPMENTS A June 3 ceasefire between Republic of Yemen Government (RoYG) forces and rival tribal groups remains in effect in Sana’a city; however, tensions remain high and individuals continue to depart the city. Increased fighting between RoYG military and militant groups in southern Yemen has resulted in additional displacement. On June 13, Vice President Abd-Rabbu Mansour Hadi met with opposition leaders for the first time since becoming the interim head of the RoYG, following President Ali Abdullah Saleh’s departure to Saudi Arabia, to discuss a peaceful end to the conflict between pro-Saleh and pro--opposition groups. USAID/OFDA is closely monitoring the security situation and reviewing emergency response contingency plans with grantees and other humanitarian agencies to facilitate a rapid and flexible response to evolving conditions. In June, USAID/OFDA committed an additional $1.5 million to the International Organization for Migration (IOM) to provide health and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) assistance for displaced individuals in Yemen. In FY 2011, USAID/OFDA has provided more than $6.4 million to support economic recovery and market systems, logistics and relief commodities, humanitarian coordination and information management, health assistance, and WASH interventions, -

Humanitarian Update

HUMANITARIAN UPDATE Issue 08 / August 2020 A displaced family at an IDP site in Al Dhale’e Governorate, February 2020. ©OCHA/YPN Mahmoud Fadel Security Council warned that the HIGHLIGHTS acute funding shortage is leading Torrential rains cause to deeper cuts to the aid operation devastation across Yemen for the third time this year and deadly consequences for the P 02 Yemeni population COVID-19 response to be On 18 August, Assistant Secretary- works or cover basic operational costs pivoted General for Humanitarian Affairs and for health facilities in the middle of a P 03 Deputy Emergency Relief Coordinator, pandemic; the closure of health facilities Mr. Ramesh Rajasingham, warned caring for 1.8 million people; and Fuel crisis seriously holds Security Council members of the reduced food aid for 8 million people back the humanitarian devastating effects that the shortage while famine is stalking the country. response in northern of humanitarian funding is having But worse is to come. Mr. Rajasingham governorate on the aid operation in Yemen. As highlighted that by the end of August, he briefed the Security Council, the without further funding, water and P 04 Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) sanitation programmes would be was 21 per cent funded, only 3 per cent reduced by 50 per cent in 15 cities; in Stranded migrants in up on the previous month, the lowest September support will stop to almost Yemen in desperate need of figure ever seen in Yemen so late in 400 more health facilities, cutting off 9 humanitarian assistance the year. “We cannot over-emphasize million people from medical care; and the severe impact the resulting cuts are treatment for over a quarter of a million P 06 having,” said Mr. -

A/HRC/45/CRP.7 29 September 2020

1 0 A/HRC/45/CRP.7 29 September 2020 English Arabic and English only Human Rights Council Forty-fifth session 14 September–2 October 2020 Agenda item 2 Annual report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and reports of the Office of the High Commissioner and the Secretary-General Situation of human rights in Yemen, including violations and abuses since September 2014 Detailed findings of the Group of Eminent International and Regional Experts on Yemen* Summary Submitted as a supplement to A/HRC/45/6, this paper sets out the detailed findings of the Group of Eminent International and Regional Experts on Yemen mandated to investigate violations by parties to the conflict since September 2014. During this year, the Group of Eminent Experts prioritised for investigation violations occurring since mid-2019, while taking a longer temporal scope for some categories of violations not fully addressed during our previous reports. The Group of Eminent Experts found reasonable grounds to believe that the parties to the conflict in Yemen are responsible for pervasive and incessant international human rights law and international humanitarian law violations, many of which may amount to war crimes. The summary of these findings is included in A/HRC/45/6. In addition to highlighting the parties to the conflict responsible for violations, the Group of Eminent Experts identified, where possible, potential perpetrators of crimes that may have been committed. A list of names of such individuals has been submitted to the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on a strictly confidential basis to assist with future accountability efforts.