Rule of Law Quick Scan Yemen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women and Participation in the Arab Uprisings: a Struggle for Justice

Distr. LIMITED E/ESCWA/SDD/2013/Technical Paper.13 26 December 2013 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMISSION FOR WESTERN ASIA (ESCWA) WOMEN AND PARTICIPATION IN THE ARAB UPRISINGS: A STRUGGLE FOR JUSTICE New York, 2013 13-0381 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper constitutes part of the research conducted by the Social Participatory Development Section within the Social Development Division to advocate the principles of social justice, participation and citizenship. Specifically, the paper discusses the pivotal role of women in the democratic movements that swept the region three years ago and the challenges they faced in the process. The paper argues that the increased participation of women and their commendable struggle against gender-based injustices have not yet translated into greater freedoms or increased political participation. More critically, in a region dominated by a patriarchal mindset, violence against women has become a means to an end and a tool to exercise control over society. If the demands for bread, freedom and social justice are not linked to discourses aimed at achieving gender justice, the goals of the Arab revolutions will remain elusive. This paper was co-authored by Ms. Dina Tannir, Social Affairs Officer, and Ms. Vivienne Badaan, Research Assistant, and has benefited from the overall guidance and comments of Ms. Maha Yahya, Chief, Social Participatory Development Section. iii iv CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... iii Chapter I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. GENDERING ARAB REVOLUTIONS: WHAT WOMEN WANT ......................... 2 A. The centrality of gender to Arab revolutions............................................................ 2 B. Participation par excellence: Activism among Arab women.................................... 3 III. CHANGING LANES: THE STRUGGLE OVER WOMEN’S BODIES ................. -

Yemen Sheila Carapico University of Richmond, [email protected]

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Political Science Faculty Publications Political Science 2013 Yemen Sheila Carapico University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/polisci-faculty-publications Part of the International Relations Commons, and the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons Recommended Citation Carapico, Sheila. "Yemen." In Dispatches from the Arab Spring: Understanding the New Middle East, edited by Paul Amar and Vijay Prashad, 101-121. New Delhi, India: LeftWord Books, 2013. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Political Science at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Political Science Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Yemen SHEILA CARAPICO IN FEBRUARY 2011, Tawakkol Karman stood on a stage outside Sanaa University. A microphone in one hand and the other clenched defiantly above her head, reading from a list of demands, she led tens of thou sands of cheering, flag-waving demonstrators in calls for peaceful politi cal change. She was to become not so much the leader as the figurehead ofYemen's uprising. On other days and in other cities, other citizens led the chants: men and women and sometimes, for effect, little children. These mass public performances enacted a veritable civic revolution in a poverty-stricken country where previous activist surges never produced democratic transitions but nonetheless did shape national history. Drawing on the Tunisiari and Egyptian inspirations as well as homegrown protest legacies, in 2011 Yemenis occupied the national commons as never before. -

The Pre-History of Self-Determination: Union and Disunion of States in Early Modern International Law

THE PRE-HISTORY OF SELF-DETERMINATION: UNION AND DISUNION OF STATES IN EARLY MODERN INTERNATIONAL LAW Han Liu* TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................ 2 I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 2 II. THE STATE AND THE NATION STATE ................................................................... 7 III. TERRITORIAL ACCESSION IN EARLY MODERN EUROPE ...................................... 9 A. The King and the Sovereign .......................................................................... 9 B. Land and Territory ....................................................................................... 15 1. Division of Realms ................................................................................... 17 2. Land and Sovereignty............................................................................... 18 3. Dynastic-Patrimonial Territoriality .......................................................... 20 4. Shape of Early Modern Territory ............................................................. 22 C. Aggregating Land: Conquest and Inheritance.............................................. 24 IV. OUTSIDE EUROPE: LAND APPROPRIATION AND COLONIAL EXPANSION........... 27 A. Just War as Civilizing Process: Vitoria’s Catholic Argument ..................... 29 B. Conquest or Settlement: Locke, Vattel, and the Protestant Argument ........ 31 V. THE JURIDICIAL -

The World Justice Project (WJP) Rule of Law Index® 2020 Board of Directors: Sheikha Abdulla Al-Misnad, Report Was Prepared by the World Justice Project

World Justice .:�=; Project World Justice Project ® Rule of Law Index 2020 The World Justice Project Rule The World Justice Project of Law Index® 2020 The World Justice Project (WJP) Rule of Law Index® 2020 Board of Directors: Sheikha Abdulla Al-Misnad, report was prepared by the World Justice Project. Kamel Ayadi, William C. Hubbard, Hassan Bubacar The Index’s conceptual framework and methodology Jallow, Suet-Fern Lee, Mondli Makhanya, Margaret were developed by Juan Carlos Botero, Mark David McKeown, William H. Neukom, John Nery, Ellen Agrast, and Alejandro Ponce. Data collection and Gracie Northfleet, James R. Silkenat and Petar Stoyanov. analysis for the 2020 report was performed by Lindsey Bock, Erin Campbell, Alicia Evangelides, Emma Frerichs, Directors Emeritus: President Dr. Ashraf Ghani Ahmadzai Joshua Fuller, Amy Gryskiewicz, Camilo Gutiérrez Patiño, Matthew Harman, Alexa Hopkins, Ayyub Officers: Mark D. Agrast, Vice President; Deborah Ibrahim, Sarah Chamness Long, Rachel L. Martin, Jorge Enix-Ross, Vice President; Nancy Ward, Vice A. Morales, Alejandro Ponce, Natalia Rodríguez President; William C. Hubbard, Chairman of the Cajamarca, Leslie Solís Saravia, Rebecca Silvas, and Board; Gerold W. Libby, General Counsel and Adriana Stephan, with the assistance of Claudia Secretary; William H. Neukom, Founder and CEO; Bobadilla, Gabriel Hearn-Desautels, Maura McCrary, James R. Silkenat, Director and Treasurer. Emma Poplack, and Francesca Tinucci. The report was produced under the executive direction of Elizabeth Executive Director: Elizabeth Andersen Andersen. Chief Research Officer: Alejandro Ponce Lead graphic designer for this report was Priyanka Khosla, with assistance from Courtney Babcock. The WJP Rule of Law Index 2020 report was made possible by the generous supporters of the work of the Lead website designer was Pitch Interactive, with World Justice Project listed in this report on page 203. -

LGBTI Rights Before the European Court of Human Rights: One Step at a Time

LGBTI RigHTS BEFORE THE EUROPEAN COUrt OF HUMAN RigHTS: ONE STEP AT A tiME Through the lens of key cases Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. Article 2: Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty. Article 3: Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person. Article 4: No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms. Article 5: No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, December 2013 / N°624f - © DIMITAR DILKOFF /AFP December 2013 / N°624f - © DIMITAR 2 / Titre du rapport – FIDH Introduction ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------4 I – Equality in the family ------------------------------------------------------------------------------6 A) Access to marriage ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------6 1) Inclusion of same-sex marriage in the scope of -

Report on Human Rights in Yemen

Report on Human Rights in Yemen Submitted by Human Rights Watch To the UN Human Rights Committee on the Occasion of its Review of Yemen in March 2012 February 1, 2012 This memorandum provides an overview of Human Rights Watch’s main concerns with respect to the human rights situation in the Republic of Yemen, submitted to the United Nations Human Rights Committee (“the Committee”) in advance of its review of Yemen in March 2012. We hope it will inform the Committee’s review of the government’s compliance with its obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (“the Covenant”). It has been seven years since Yemen last submitted its State Report to the Committee. During this time, the government has engaged in systematic violations of the Covenant, including extensive restrictions on the rights to freedom of expression, peaceful assembly, and association, and the use of ill-treatment and unfair trials of political detainees. Yemen continues to have one of the highest execution rates in the world. The government dramatically intensified its targeting of human rights defenders and journalists during its suppression of a secessionist movement in the south starting in 2007, and during nationwide protests seeking the resignation of President Ali Abdullah Saleh in 2011. Yemen submitted its latest report to the Committee 14 months before the state’s security forces began a violent crackdown against largely peaceful demonstrators and opposition activists demanding the resignation of President Saleh.1 Attacks by pro-government gangs 1 Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 40 of the Covenant, Fifth periodic report of States parties, Yemen, CCPR/C/YEM/5, December 14, 2009, http://daccess-ods.un.org/TMP/8811841.01104736.html. -

Assessment of the Impact of Trade Policy Reform in Countries Acceding

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT AASSESSMENT OF THE IIMPACT OF TTRADE PPOLICY RREFORM IN CCOUNTRIES AACCEDING TO THE WWORLD TTRADE OORGANIZATION:: TTHE GGENDER DDIMENSION A STUDY PREPARED UNDER THE UNCTAD TRUST FUND FOR WTO ACCESSIONS, PHASE 3 United Nations New York and Geneva, 2010 ASSESSMENT OF THE IMPACT OF TRADE POLICY REFORM IN COUNTIRES ACCEDING TO THE WTO: THE GENDER DIMENSION NNNOOOTTTEEE • The symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. • The views expressed in this volume are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the UNCTAD secretariat or its member States. The designations employed and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Secretariat concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or regarding its economic system or degree of development. • Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgement is requested, together with a reference to the document number. A copy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint should be sent to the UNCTAD secretariat at: Palais des Nations, 1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland. Series Editor: Ms. Mina Mashayekhi Head, Trade Negotiations and Commercial Diplomacy Branch Division on International Trade in Goods and Services, and Commodities United Nations Conference on Trade and Development Palais des Nations CH-1211 Geneva 10 UNCTAD/DITC/TNCD/2010/6 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION ISSN 1816-2878 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AAACCCKKKNNNOOOWWWLLLEEEDDDGGGEEEMMMEEENNNTTTSSS This study was undertaken under the framework of the UNCTAD Trust Fund for WTO Accessions, Phase 3. -

Yemen's National Dialogue

arab uprisings Yemen’s National Dialogue March 21, 2013 MOHAMMED HUWAIS/AFP/GETTY IMAGES HUWAIS/AFP/GETTY MOHAMMED POMEPS Briefings 19 Contents Overcoming the Pitfalls of Yemen’s National Dialogue . 5 Consolidating Uncertainty in Yemen . 7 Can Yemen be a Nation United? . 10 Yemen’s Southern Intifada . 13 Best Friends Forever for Yemen’s Revolutionaries? . 18 A Shake Up in Yemen’s GPC? . 21 Hot Pants: A Visit to Ousted Yemeni Leader Ali Abdullah Saleh’s New Presidential Museum . .. 23 Triage for a fracturing Yemen . 26 Building a Yemeni state while losing a nation . 32 Yemen’s Rocky Roadmap . 35 Don’t call Yemen a “failed state” . 38 The Project on Middle East Political Science The Project on Middle East Political Science (POMEPS) is a collaborative network which aims to increase the impact of political scientists specializing in the study of the Middle East in the public sphere and in the academic community . POMEPS, directed by Marc Lynch, is based at the Institute for Middle East Studies at the George Washington University and is supported by the Carnegie Corporation and the Social Science Research Council . It is a co-sponsor of the Middle East Channel (http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com) . For more information, see http://www .pomeps .org . Online Article Index Overcoming the Pitfalls of Yemen’s National Dialogue http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com/posts/2013/03/18/overcoming_the_pitfalls_of_yemen_s_national_dialogue Consolidating Uncertainty in Yemen http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com/posts/2013/02/22/consolidating_uncertainty_in_yemen -

An Estimated 5 Billion People Have Unmet Justice Needs Globally. This

An estimated 5 billion people have unmet justice needs globally. This justice gap includes people who cannot obtain justice for everyday problems, people who are excluded from the opportunity the law provides, and people who live in extreme conditions of injustice. 6 February 2019 I. Introduction The Justice For All report of the Task Force on Justice describes a global justice gap of 5 billion people, underscoring the urgency of realizing justice for all and demonstrating unacceptable levels of exclusion from justice. This methodological note provides an update on the progress and methodological decisions that have been made since the October 2018 meeting of the Task Force on Justice in Sierra Leone (see Box 1), as well as the broader background, development process, and measurement approach for arriving at this figure. This information is organized in the following sections: I. Introduction, including the background, objectives, and principles guiding the justice gap assessment. II. Data Design for Measuring the Justice Gap, covering the development of measurement questions, selection of data sources, and development process to date. III. Measures, Definitions & Methods, describing the definition and methodology for calculating each measure included in the justice gap framework. The justice gap estimates presented in this note and described in the Justice For All report represent the first- ever effort to integrate survey data with other sources of people-centered data on the nature and scale of injustice. This synthesis was conducted -

Situation of Human Rights in Yemen, Including Violations and Abuses Since September 2014

United Nations A/HRC/39/43* General Assembly Distr.: General 17 August 2018 Original: English Human Rights Council Thirty-ninth session 10–28 September 2018 Agenda items 2 and 10 Annual report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and reports of the Office of the High Commissioner and the Secretary-General Technical assistance and capacity-building Situation of human rights in Yemen, including violations and abuses since September 2014 Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights containing the findings of the Group of Eminent International and Regional Experts and a summary of technical assistance provided by the Office of the High Commissioner to the National Commission of Inquiry** Summary The present report is being submitted to the Human Rights Council in accordance with Council resolution 36/31. Part I of the report contains the findings, conclusions and recommendations of the Group of Eminent International and Regional Experts on Yemen. Part II provides an account of the technical assistance provided by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights to the National Commission of Inquiry into abuses and violations of human rights in Yemen. * Reissued for technical reasons on 27 September 2018. ** The annexes to the present report are circulated as received, in the language of submission only. GE.18-13655(E) A/HRC/39/43 Contents Page I. Findings of the Group of Eminent International and Regional Experts on Yemen ....................... 3 A. Introduction and mandate .................................................................................................... -

Report on the Nutritional Situation and Mortality Survey Al Jawf

Republic of Yemen Ministry of Public Health and Population Central Statistical Organization Report on the Nutritional Situation and Mortality Survey Al Jawf Governorate, Yemen From 19 to 25 April 2018 1 Acknowledgment The Ministry of Public Health and Population in Yemen, represented by the Public Health and Population Office in the Al Jawf governorate and in cooperation with the UNICEF country office in Yemen and the UNICEF branch in Sana’a, acknowledges the contribution of different stakeholders in this survey. The UNICEF country office in Yemen provided technical support, using the SMART methodology, while the survey manager and his assistants from the Ministry of Public Health and Population and the Public Health and Population Offices in Amran and Taiz were also relied on. The surveyors and team heads were provided by the Public Health and Population Office in the Al Jawf governorate. The data entry team was provided by the Public Health and Population Office in Amran and the Nutrition Department in the Ministry. The survey protocol was prepared, and other changes were made to it, through cooperation between the Ministry of Public Health and Population and the Central Statistical Organization, with technical support from UNICEF. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development provided UNICEF with technical assistance, especially with regards to daily quality checks, data analysis, and report writing. The Building Foundation for Development provided technical and logistical support through extensive coordination with the local authorities in the Al Jawf governorate, as well as through their choice of the survey team and providing extensive training for them. The Building Foundation for Development was also responsible for regular follow-up with the survey teams out in the field and providing logistical and technical support for these teams, as well as preparing the initial draft of the survey report. -

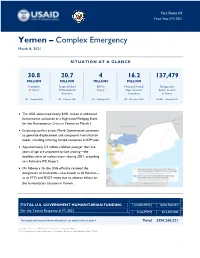

2021 03 08 USG Yemen Complex Emergency Fact Sheet #2

Fact Sheet #2 Fiscal Year (FY) 2021 Yemen – Complex Emergency March 8, 2021 SITUATION AT A GLANCE 30.8 20.7 4 16.2 137,479 MILLION MILLION MILLION MILLION Population People in Need IDPs in Projected Acutely Refugees and of Yemen of Humanitarian Yemen Food- Insecure Asylum Seekers Assistance Population in Yemen UN – February 2021 UN – February 2021 UN – February 2021 IPC – December 2020 UNHCR – February 2021 The USG announced nearly $191 million in additional humanitarian assistance at a High-Level Pledging Event for the Humanitarian Crisis in Yemen on March 1. Escalating conflict across Marib Governorate continues to generate displacement and compound humanitarian needs, including straining limited resources at IDP sites. Approximately 2.3 million children younger than five years of age are projected to face wasting—the deadliest form of malnutrition—during 2021, according to a February IPC Report. On February 16, the USG officially revoked the designation of Ansarallah—also known as Al Houthis— as an FTO and SDGT entity due to adverse effects on the humanitarian situation in Yemen. TOTAL U.S. GOVERNMENT HUMANITARIAN FUNDING USAID/BHA1 $336,760,221 For the Yemen Response in FY 2021 2 State/PRM $13,500,000 For complete funding breakdown with partners, see detailed chart on page 6 Total $350,260,221 1 USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA). 2 U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (State/PRM). 1 KEY DEVELOPMENTS USG Announces $191 Million at Humanitarian Pledging Conference The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and the governments of Sweden and Switzerland virtually hosted a High-Level Pledging Event for the Humanitarian Crisis in Yemen on March 1.