A/HRC/45/CRP.7 29 September 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CORVINUS UNIVERSITY of BUDAPEST INTERSTATE RIVALS' INTERVENTION in THIRD PARTY CIVIL WARS: the Comparative Case of Saudi Arabi

CORVINUS UNIVERSITY OF BUDAPEST INTERSTATE RIVALS’ INTERVENTION IN THIRD PARTY CIVIL WARS: The comparative case of Saudi Arabia and Iran in Yemen (2004-2018) DOCTORAL DISSERTATION Supervisor: Marton Péter, Phd Associate Professor Palik Júlia Budapest, 2020 Palik Júlia Interstate rivals’ intervention in third-party civil wars: The comparative case of Saudi Arabia and Iran in Yemen (2004-2018) Institute of International Studies Supervisor: Marton Péter,Phd Associate Professor © Palik Júlia Corvinus University of Budapest International Relations Multidisciplinary Doctoral School Interstate rivals’ intervention in third-party civil wars: The comparative case of Saudi Arabia and Iran in Yemen (2004-2018) Doctoral Dissertation Palik Júlia Budapest, 2020 Table of Content List of Tables, Figures, and Maps....................................................................................................................................... 9 Abstract ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 12 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................................... 9 1. RESEARCH DESIGN ................................................................................................................................................. 12 1.2. Methodology ........................................................................................................................................................... -

Stand Alone End of Year Report Final

Shelter Cluster Yemen ShelterCluster.org 2019 Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter SHELTER CLUSTER End Year Report Shelter Cluster Yemen Foreword Yemeni people continue to show incredible aspirations and the local real estate market and resilience after ve years of conict, recurrent ood- environmental conditions: from rental subsidies ing, constant threats of famine and cholera, through cash in particular to prevent evictions extreme hardship to access basic services like threats to emergency shelter kits at the onset of a education or health and dwindling livelihoods displacement, or winterization upgrading of opportunities– and now, COVID-19. Nearly four shelters of those living in mountainous areas of million people have now been displaced through- Yemen or in sites prone to ooding. Both displaced out the country and have thus lost their home. and host communities contributed to the design Shelter is a vital survival mechanism for those who and building of shelters adapted to the Yemeni have been directly impacted by the conict and context, resorting to locally produced material and had their houses destroyed or have had to ee to oering a much-needed cash-for-work opportuni- protect their lives. Often overlooked, shelter inter- ties. As a result, more than 2.1 million people bene- ventions provide a safe space where families can tted from shelter and non-food items interven- pause and start rebuilding their lives – protected tions in 2019. from the elements and with the privacy they are This report provides an overview of 2019 key entitled to. Shelters are a rst step towards achievements through a series of maps and displaced families regaining their dignity and build- infographics disaggregated by types of interven- ing their self-reliance. -

Mocha: Maritime Architecture on Yemen's Red Sea Coast

Binghamton University The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB) Art History Faculty Scholarship Art History 2017 “Mocha: Maritime Architecture on Yemen’s Red Sea Coast.” In ‘Architecture That Fills My Eye’: The Building Heritage of Yemen. Exh. Cat. Ed. Trevor H.J. Marchand, 60-69. London: Gingko Library, 2017. Nancy Um Binghamton University--SUNY, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/art_hist_fac Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Nancy Um, “Mocha: Maritime Architecture on Yemen’s Red Sea Coast.” In ‘Architecture That Fills My Eye’: The Building Heritage of Yemen. Exh. Cat. Ed. Trevor H.J. Marchand, 60-69. London: Gingko Library, 2017. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Art History Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. GINGKO LIBRARY ART SERIES Senior Editor: Melanie Gibson Architectural Heritage of Yemen Buildings that Fill my Eye Edited by Trevor H.J. Marchand First published in 2017 by Gingko Library 70 Cadogan Place, London SW1X 9AH Copyright © 2017 selection and editorial material, Trevor H. J. Marchand; individual chapters, the contributors. The rights of Trevor H. J. Marchand to be identified as the author of the editorial material, and of the individual authors as authors of their contributions, has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Download File

Yemen Country Office Humanitarian Situation Report ©UNICEF Yemen/2019/Mahmoud Fadhel Reporting Period: 1 - 31 October 2019 Highlights Situation in Numbers • In October, 3 children were killed, 16 children were injured and 3 12.3 million children in need of boys were recruited by various parties to the conflict. humanitarian assistance • 59,297 suspected Acute Watery Diarrhoea (AWD)/cholera cases were identified and 50 associated deaths were recorded (0.08 case 24.1 million fatality rate) in October. UNICEF treated over 14,000 AWD/cholera people in need suspected cases (one quarter of the national caseload). (OCHA, 2019 Yemen Humanitarian Needs Overview) • Due to fuel crisis, in Ibb, Dhamar and Al Mahwit, home to around 400,000 people, central water systems were forced to shut down 1.71 million completely. children internally displaced • 3.1 million children under five were screened for malnutrition, and (IDPs) 243,728 children with Severe Acute Malnutrition (76 per cent of annual target) admitted for treatment. UNICEF Appeal 2019 UNICEF’s Response and Funding Status US$ 536 million Funding Available* SAM Admission 76% US$ 362 million Funding status 68% Nutrition Measles Rubella Vaccination 91% Health Funding status 77% People with drinking water 100% WASH Funding status 64% People with Mine Risk Education 82% Child Funding status 40% Protection Children with Access to Education 29% Funding status 76% Education People with Social Economic 61% Assistance Policy Social Funding status 38% People reached with C4D efforts 100% *Funds available includes funding received for the current C4D Funding status 98% appeal (emergency and other resources), the carry- forward from the previous year and additional funding Displaced People with RRM Kits 59% which is not emergency specific but will partly contribute towards 2019 HPM results. -

Yemen's National Dialogue

arab uprisings Yemen’s National Dialogue March 21, 2013 MOHAMMED HUWAIS/AFP/GETTY IMAGES HUWAIS/AFP/GETTY MOHAMMED POMEPS Briefings 19 Contents Overcoming the Pitfalls of Yemen’s National Dialogue . 5 Consolidating Uncertainty in Yemen . 7 Can Yemen be a Nation United? . 10 Yemen’s Southern Intifada . 13 Best Friends Forever for Yemen’s Revolutionaries? . 18 A Shake Up in Yemen’s GPC? . 21 Hot Pants: A Visit to Ousted Yemeni Leader Ali Abdullah Saleh’s New Presidential Museum . .. 23 Triage for a fracturing Yemen . 26 Building a Yemeni state while losing a nation . 32 Yemen’s Rocky Roadmap . 35 Don’t call Yemen a “failed state” . 38 The Project on Middle East Political Science The Project on Middle East Political Science (POMEPS) is a collaborative network which aims to increase the impact of political scientists specializing in the study of the Middle East in the public sphere and in the academic community . POMEPS, directed by Marc Lynch, is based at the Institute for Middle East Studies at the George Washington University and is supported by the Carnegie Corporation and the Social Science Research Council . It is a co-sponsor of the Middle East Channel (http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com) . For more information, see http://www .pomeps .org . Online Article Index Overcoming the Pitfalls of Yemen’s National Dialogue http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com/posts/2013/03/18/overcoming_the_pitfalls_of_yemen_s_national_dialogue Consolidating Uncertainty in Yemen http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com/posts/2013/02/22/consolidating_uncertainty_in_yemen -

EPSE PROFILE-19Th Edition

Electrical Power Systems Establishment PROFILE 19th EDITION May, 2019 www.eps-est.com TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 2.0 ORGANIZATION INFORMATION 3.0 MESSAGES 3.1 MISSION 3.2 VISION 3.3 COMMITMENT STATEMENT 3.4 QA/QC STATEMENT 3.5 SAFETY STATMENT 4.0 ORGANIZATION CHART 5.0 AFFILIATIONS 6.0 RESOURCES LISTING 6.1 MANPOWER 6.2 CONSTRUCTION EQUIPMENT & TOOLS 6.3 TESTING EQUIPMENT 7.0 BRIEF BUSINESS EXPOSURE 7.1 EQUIPMENT EXPERTISE 7.2 SERVICES 7.3 MAIN CUSTOMERS LIST 8.0 PROJECT LISTING 8.1 ON GOING JOBS 8.2 COMPLETED JOBS Electrical Power Systems Est. Profile 19th Edition May, 2019 PAGE 2 OF 33 1.0 INTRODUCTION Electrical Power Systems Est., (EPSE) was founded in 1989 under the name of Electronics Systems Est. (ESE). Established primarily to provide general services in instrumentation, calibration and personal computer trade, it then revolutionized its interests to the more technical field of Control and Monitoring Systems primarily for the Electric Power utilities. Within a short period of time in this new field of interest, it has achieved a remarkable and outstanding performance that gained the appreciation and acknowledgment of fine clients such as ABB, which from thence entrusted sensitive related jobs to the Establishment. Realizing the soaring demand for services in this specialized field and where only few Saudi firms have ventured, the management was prompted to enhance and confine ESE activities within the bounds of Electric Power Control and Monitoring Systems. In late 1998, Electronics Systems Est. (ESE) was renamed Electrical Power Systems Establishment (EPSE) to appropriately symbolize its specialized activities in the field of Electricity. -

The Thermopylae Line

CHAPTER 6 THE THERMOPYLAE LINE ENERAL Wavell arrived in Athens on the 19th April and immediately e Gheld a conference at General Wilson's quarters . Although an effectiv decision to embark the British force from Greece had been made on a higher level in London, the commanders on the spot now once agai n deeply considered the pros and cons . The Greek Government was unstable and had suggested that the British force should depart in order to avoid further devastation of the country. It was unlikely that the Greek Army of Epirus could be extricated and some of its senior officers were urging sur- render. General Wilson considered that his force could hold the Ther- mopylae line indefinitely once the troops were in position.l "The arguments in favour of fighting it out, which [it] is always better to do if possible, " wrote Wilson later,2 "were : the tying up of enemy forces, army and air , which would result therefrom ; the strain the evacuation would place o n the Navy and Merchant Marine ; the effect on the morale of the troops and the loss of equipment which would be incurred . In favour of with- drawal the arguments were : the question as to whether our forces in Greece could be reinforced as this was essential ; the question of the maintenance of our forces, plus the feeding of the civil population ; the weakness of our air forces with few airfields and little prospect of receiving reinforcements ; the little hope of the Greek Army being able to recover its morale . The decision was made to withdraw from Greece ." The British leaders con- sidered that it was unlikely that they would be able to take out any equip- ment except that which the troops carried, and that they would be lucky "to get away with 30 per cent of the force" . -

The Adaptive Transformation of Yemen?S Republican Guard

The Adaptive Transformation of Yemen's Republican Guard By Lucas Winter Journal Article | Mar 7 2017 - 9:45pm The Adaptive Transformation of Yemen’s Republican Guard Lucas Winter In the summer of 1978, Colonel Ali Abdullah Saleh became president of the Yemeni Arab Republic (YAR) or North Yemen. Like his short-lived predecessor Ahmad al-Ghashmi, Saleh had been a tank unit commander in the YAR military before ascending the ranks.[1] Like al-Ghashmi, Saleh belonged to a tribe with limited national political influence but a strong presence in the country’s military.[2] Three months into Saleh’s presidency, conspirators allied with communists from the Popular Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY), or South Yemen, staged a coup and briefly seized key government installations in the capital Sana’a. The 1st Armored Brigade, North Yemen’s main tank unit at the time, was deployed to quell the insurrection. The 1st Armored Brigade subsequently expanded to become the 1st Armored Division. Commanded by Saleh’s kinsman Ali Muhsin al-Ahmar, it became North Yemen’s premiere military unit and took control of vital installations in the capital. The division played a decisive role in securing victory for Saleh and his allies in Yemen’s 1994 Civil War. Although the 1st Armored Division functioned as President Saleh’s Praetorian Guard, his personal safety was in the hands of the Yemeni Republican Guard (YRG), a small force created with Egyptian support in the early days of the republic.[3] YRG headquarters were in “Base 48,” located on the capital’s southern outskirts abutting the territories of Saleh’s Sanhan tribe. -

2021 03 08 USG Yemen Complex Emergency Fact Sheet #2

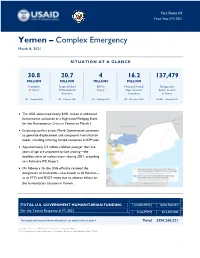

Fact Sheet #2 Fiscal Year (FY) 2021 Yemen – Complex Emergency March 8, 2021 SITUATION AT A GLANCE 30.8 20.7 4 16.2 137,479 MILLION MILLION MILLION MILLION Population People in Need IDPs in Projected Acutely Refugees and of Yemen of Humanitarian Yemen Food- Insecure Asylum Seekers Assistance Population in Yemen UN – February 2021 UN – February 2021 UN – February 2021 IPC – December 2020 UNHCR – February 2021 The USG announced nearly $191 million in additional humanitarian assistance at a High-Level Pledging Event for the Humanitarian Crisis in Yemen on March 1. Escalating conflict across Marib Governorate continues to generate displacement and compound humanitarian needs, including straining limited resources at IDP sites. Approximately 2.3 million children younger than five years of age are projected to face wasting—the deadliest form of malnutrition—during 2021, according to a February IPC Report. On February 16, the USG officially revoked the designation of Ansarallah—also known as Al Houthis— as an FTO and SDGT entity due to adverse effects on the humanitarian situation in Yemen. TOTAL U.S. GOVERNMENT HUMANITARIAN FUNDING USAID/BHA1 $336,760,221 For the Yemen Response in FY 2021 2 State/PRM $13,500,000 For complete funding breakdown with partners, see detailed chart on page 6 Total $350,260,221 1 USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA). 2 U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (State/PRM). 1 KEY DEVELOPMENTS USG Announces $191 Million at Humanitarian Pledging Conference The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and the governments of Sweden and Switzerland virtually hosted a High-Level Pledging Event for the Humanitarian Crisis in Yemen on March 1. -

Security Council Distr.: General 27 January 2020

United Nations S/2020/70 Security Council Distr.: General 27 January 2020 Original: English Letter dated 27 January 2020 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen addressed to the President of the Security Council The members of the Panel of Experts on Yemen have the honour to transmit herewith the final report of the Panel, prepared in accordance with paragraph 6 of resolution 2456 (2019). The report was provided to the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 2140 (2014) on 27 December 2019 and was considered by the Committee on 10 January 2020. We would appreciate it if the present letter and the report were brought to the attention of the members of the Security Council and issued as a document of the Council. (Signed) Dakshinie Ruwanthika Gunaratne Coordinator Panel of Experts on Yemen (Signed) Ahmed Himmiche Expert (Signed) Henry Thompson Expert (Signed) Marie-Louise Tougas Expert (Signed) Wolf-Christian Paes Expert 19-22391 (E) 070220 *1922391* S/2020/70 Final report of the Panel of Experts on Yemen Summary After more than five years of conflict, the humanitarian crisis in Yemen continues. The country’s many conflicts are interconnected and can no longer be separated by clear divisions between external and internal actors and events. Throughout 2019, the Houthis and the Government of Yemen made little headway towards either a political settlement or a conclusive military victory. In a continuation from 2018, the belligerents continued to practice economic warfare: using economic obstruction and financial tools as weapons to starve opponents of funds or materials. Profiteering from the conflict is endemic. -

The Final Campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year The final campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945 Karl James University of Wollongong James, Karl, The final campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945, PhD thesis, School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2005. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/467 This paper is posted at Research Online. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/467 The Final Campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy from University of Wollongong by Karl James, BA (Hons) School of History and Politics 2005 i CERTIFICATION I, Karl James, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, is wholly my work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Karl James 20 July 2005 ii Table of Contents Maps, List of Illustrations iv Abbreviations vi Conversion viii Abstract ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1 ‘We have got to play our part in it’. Australia’s land war until 1944. 15 2 ‘History written is history preserved’. History’s treatment of the Final Campaigns. 30 3 ‘Once the soldier had gone to war he looked for leadership’. The men of the II Australian Corps. 51 4 ‘Away to the north of Queensland, On the tropic shores of hell, Stand grimfaced men who watch and wait, For a future none can tell’. The campaign takes shape: Torokina and the Outer Islands. -

June 2013 - February 2014

Yemen outbreak June 2013 - February 2014 Desert Locust Information Service FAO, Rome www.fao.org/ag/locusts Keith Cressman (Senior Locust Forecasting Officer) SAUDI ARABIA spring swarm invasion (June) summer breeding area Thamud YEMEN Sayun June 2013 Marib Sanaa swarms Ataq July 2013 groups April and May 2013 rainfall totals adults 25 50 100+ mm Aden hoppers source: IRI RFE JUN-JUL 2013 Several swarms that formed in the spring breeding areas of the interior of Saudi Arabia invaded Yemen in June. Subsequent breeding in the interior due to good rains in April-May led to an outbreak. As control operations were not possible because of insecurity and beekeepers, hopper and adult groups and small hopper bands and adult swarms formed. DLIS Thamud E M P T Y Q U A R T E R summer breeding area SEP Suq Abs Sayun winter Marib Sanaa W. H A D H R A M A U T breeding area Hodeidah Ataq Aug-Sep 2013 swarms SEP bands groups adults Aden breeding area winter hoppers AUG-SEP 2013 Breeding continued in the interior, giving rise to hopper bands and swarms by September. Survey and control operations were limited due to insecurity and beekeeping and only 5,000 ha could be treated. Large areas could not be accessed where bands and swarms were probably forming. Adults and adult groups moved to the winter breeding areas along the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden coasts where early first generation egg-laying and hatching caused small hopper groups and bands to DLIS form. Ground control operations commenced on 27 September.