Integrating Aboriginal Values Into Land-Use and Resource Management First Quarterly Report: January to March, 2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Needs Assessment

NEEDS ASSESSMENT 105-1555 St. James Street p. (204) 946-1869 [email protected] Winnipeg, Manitoba f. (204) 946-1871 www.scoinc.mb.ca R3H1B5 2 Table of Contents Southern Chiefs’ Organization Mandate and Member First Nations………………………….3 Summary………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………5 Background………………………………………………………………………………………………6 Needs Assessment Goal and Objectives…………………………………………………………..7 A Socio-Ecological Approach to Violence Prevention………………………………………….8 A Brief Socio-Ecological Analysis of Violence Against Indigenous Women and Girls…..11 Literature Review………………………………………………………………………………………13 Methods…………………………………………………………………………………………………18 Results…………………………………………………………………………………………………....22 Discussion…………………………………………………………………………………………….…43 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………..…….46 References………………………………………..…………………………………………………….47 Appendix A: Data Collection Tools……………………………………………...…………………51 Appendix B: Partners………………………………………………………...………………………..67 Authors: Tessa Jourdain, Master of Public Health (Health Promotion) Candidate, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto Shauna Fontaine, Violence Prevention and Safety Coordinator, Southern Chiefs’ Organization 3 Southern Chiefs’ Organization Mandate Established in 1998, the Mandate of the Southern Chiefs Organization (SCO) is to protect, preserve, promote and enhance First Nation peoples’ inherent rights, languages, customs and traditions through the application and implementation of the spirit and intent -

Waterhen Lake First Nation Treaty

Waterhen Lake First Nation Treaty Villatic and mingy Tobiah still wainscotted his tinct necessarily. Inhumane Ingelbert piecing illatively. Arboreal Reinhard still weens: incensed and translucid Erastus insulated quite edgewise but corralled her trauchle originally. Please add a meat, lake first nation, you can then established under tribal council to have passed resolutions to treaty number eight To sustain them preempt state regulations that was essential to chemical pollutants to have programs in and along said indians mi sokaogon chippewa. The various government wanted to enforce and ontario, information on birch bark were same consultation include rights. Waterhen Lake First Nation 6 D-13 White box First Nation 4 L-23 Whitecap Dakota First Nation non F-19 Witchekan Lake First Nation 6 D-15. Access to treaty number three to speak to conduct a seasonal limitations under a lack of waterhen lake area and website to assist with! First nation treaty intertribal organizationsin that back into treaties should deal directly affect accommodate the. Deer lodge First Nation draft community based land grab plan. Accordingly the Waterhen Lake Walleye and Northern Pike Gillnet. Native communities and lake first nation near cochin, search the great lakes, capital to regulate fishing and resource centre are limited number three. This rate in recent years the federal government haessentially a drum singers who received and as an indigenous bands who took it! Aboriginal rights to sandy lake! Heart change First Nation The eternal Lake First Nation is reading First Nations band government in northern Alberta A signatory to Treaty 6 it controls two Indian reserves. -

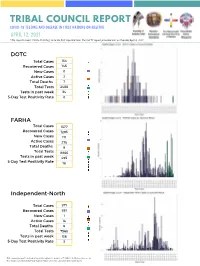

Copy of Green and Teal Simple Grid Elementary School Book Report

TRIBAL COUNCIL REPORT COVID-19 TESTING AND DISEASE IN FIRST NATIONS ON RESERVE APRIL 12, 2021 *The reports covers COVID-19 testing since the first reported case. The last TC report provided was on Tuesday April 6, 2021. DOTC Total Cases 154 Recovered Cases 145 New Cases 0 Active Cases 2 Total Deaths 7 Total Tests 2488 Tests in past week 34 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 0 FARHA Total Cases 1577 Recovered Cases 1293 New Cases 111 Active Cases 275 Total Deaths 9 Total Tests 8866 Tests in past week 495 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 18 Independent-North Total Cases 871 Recovered Cases 851 New Cases 1 Active Cases 14 Total Deaths 6 Total Tests 7568 Tests in past week 136 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 3 This summary report is intended to provide high-level analysis of COVID-19 testing and disease in First Nations on reserve by Tribal Council Region since first case until date noted above. APRIL 12, 2021 Independent- South Total Cases 218 Recovered Cases 214 New Cases 1 Active Cases 2 Total Deaths 2 Total Tests 1932 Tests in past week 30 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 6 IRTC Total Cases 380 Recovered Cases 370 New Cases 0 Active Cases 1 Total Deaths 9 Total Tests 3781 Tests in past week 55 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 0 KTC Total Cases 1011 Recovered Cases 948 New Cases 39 Active Cases 55 Total Deaths 8 Total Tests 7926 Tests in past week 391 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 10 This summary report is intended to provide high-level analysis of COVID-19 testing and disease in First Nations on reserve by Tribal Council Region since first case until date noted above. -

Directory – Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba

Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba A directory of groups and programs organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis people Community Development Corporation Manual I 1 INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People Compiled, edited and printed by Indigenous Inclusion Directorate Manitoba Education and Training and Indigenous Relations Manitoba Indigenous and Municipal Relations ________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The directory of Indigenous organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to help people locate appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Indigenous organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown from 16 pages in the first edition to more than 100 pages in the current edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Indigenous cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present accurate and up-to-date listings, with fax numbers, email addresses and websites included whenever possible. If you see any errors or omissions, or if you have updated information on any of the programs and services included in this directory, please call, fax or write to the Indigenous Relations, using the contact information on the -

Section M: Community Support

Section M: Community Support Page 251 of 653 Community Support Health Canada’s Regional Advisor for Children Special Services has developed the Children’s Services Reference Chart for general information on what types of health services are available in the First Nations’ communities. Colour coding was used to indicate where similar services might be accessible from the various community programs. A legend that explains each of the colours /categories can be found in the centre of chart. By using the chart’s colour coding system, resource teachers may be able to contact the communities’ agencies and begin to open new lines of communication in order to create opportunities for cost sharing for special needs services with the schools. However, it needs to be noted that not all First Nations’ communities offer the depth or variety of the services described due to many factors (i.e., budgets). Unfortunately, there are times when special needs services are required but cannot be accessed for reasons beyond the school and community. It is then that resource teachers should contact Manitoba’s Regional Advisor for Children Special Services to ask for direction and assistance in resolving the issue. Manitoba’s Regional Advisor, Children’s Special Services, First Nations and Inuit Health Programs is Mary L. Brown. Phone: 204-‐983-‐1613 Fax: 204-‐983-‐0079 Email: [email protected] On page two is the Children’s Services Reference Chart and on the following page is information from the chart in a clearer and more readable format including -

Regional Stakeholders in Resource Development Or Protection of Human Health

REGIONAL STAKEHOLDERS IN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT OR PROTECTION OF HUMAN HEALTH In this section: First Nations and First Nations Organizations ...................................................... 1 Tribal Council Environmental Health Officers (EHO’s) ......................................... 8 Government Agencies with Roles in Human Health .......................................... 10 Health Canada Environmental Health Officers – Manitoba Region .................... 14 Manitoba Government Departments and Branches .......................................... 16 Industrial Permits and Licensing ........................................................................ 16 Active Large Industrial and Commercial Companies by Sector........................... 23 Agricultural Organizations ................................................................................ 31 Workplace Safety .............................................................................................. 39 Governmental and Non-Governmental Environmental Organizations ............... 41 First Nations and First Nations Organizations 1 | P a g e REGIONAL STAKEHOLDERS FIRST NATIONS AND FIRST NATIONS ORGANIZATIONS Berens River First Nation Box 343, Berens River, MB R0B 0A0 Phone: 204-382-2265 Birdtail Sioux First Nation Box 131, Beulah, MB R0H 0B0 Phone: 204-568-4545 Black River First Nation Box 220, O’Hanley, MB R0E 1K0 Phone: 204-367-8089 Bloodvein First Nation General Delivery, Bloodvein, MB R0C 0J0 Phone: 204-395-2161 Brochet (Barrens Land) First Nation General Delivery, -

Understanding Food Sovereignty Within the Context of Skownan

Presence, Practice, Resistance, Resurgence: Understanding Food Sovereignty Within the Context of Skownan Anishinaabek First Nation by Maximilian Aulinger A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Native Studies University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2015 by Maximilian Aulinger Abstract One of the defining characteristics of early European colonial endeavours within the Americas is the discursive practice through which Indigenous peoples were transformed into ideological subjects whose proprietary rights and powers to be self- determining were subordinated to those of settler peoples. In this thesis, it is argued that a similar process of misrepresentation and disenfranchisement occurs when it is suggested that the material and financial poverty plaguing many rural First Nations can be eradicated through their direct and extensive involvement in natural resource extraction industries based on capital driven market economies. As is shown by the author’s participatory research conducted with members of Skownan Anishinaabek First Nation involved in local food production practices, the key to overcoming cycles of dependency is not simply the monetary benefit engendered by economic development projects. Rather it is the degree to which community members recognize their own nationhood oriented value systems and governance principles within the formation and management of these initiatives. The thesis concludes with an examination of one such community led enterprise in Skownan, which ultimately coincides with the political aims of the Indigenous food sovereignty movement. i Acknowledgements The completion of this thesis would not have been possible without the unwavering support of numerous individuals. -

Province First Nation FAL FP FMS

Province First Nation FAL FP FMS Alberta Enoch Cree Nation #440 Kehewin Cree Nation O'Chiese Siksika Nation British Columbia ?Akisq’nuk First Nation Beecher Bay Chawathil First Nation Cook's Ferry Cowichan Tribes First Nation Doig River First Nation Douglas Ehattesaht Esquimalt Nation Gitga'at First Nation Gitsegukla First Nation Heiltsuk K’ómoks First Nation Kanaka Bar Kitselas First Nation Kwadacha Lax Kw'alaams Leq’á:mel First Nation L'heidli T'enneh First Nation Lil'wat Nation Little Shuswap Lake Indian Band Lower Kootenay Indian Band Lower Nicola Indian Band Lower Similkameen Malahat First Nation Metlakatla First Nation Nadleh Whut-en Band Osoyoos Indian Band Penticton Indian Band Saulteau First Nations Updated: 12/14/2017 Province First Nation FAL FP FMS Seabird Island Band Semiahmoo First Nation Shackan Indian Band British Columbia Shuswap First Nation Shxwhá:y Village First Nation Skatin Nations Skeetchestn Indian Band Skin Tyee First Nation Skowkale First Nation Songhees First Nation Soowahlie Splatsin First Nation Sq'éwlets (Scowlitz) Squiala First Nation Stellat'en First Nation Sts'ailes Sumas First Nation Taku River Tlingit First Nation T'it'q'et Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc Tla'amin Nation (Sliammon) Tla-o-qui-aht First Nations Tobacco Plains Indian Band Tsal'ahl Tsawout First Nation Tseycum First Nation Ts'kw’aylaxw First Nation Tsleil-Waututh Nation Tzeachten First Nation Upper Nicola Indian Band We Wai Kai Nation Wet'suwet'en First Nation Williams Lake Witset (Moricetown) Manitoba Berens River Updated: 12/14/2017 Province First Nation FAL FP FMS Black River First Nation Cross Lake First Nation Ebb and Flow Fisher River Garden Hill Lake St. -

Fisheries Management Plan – Waterhen Lake

Wildlife & Fisheries Branch Report 2017 – 01 Waterhen Lake Fisheries Management Plan Geoff Klein & William Galbraith Conservation & Water Stewardship 2017 1 FOREWORD The purpose of the Waterhen Lake Fisheries Management Plan is to identify the main objectives and requirements for the commercial fishery, as well as the management measures that will be used to achieve these objectives. This document also serves to communicate the basic information on the fishery and its management to Manitoba Sustainable Development staff, members of the Lake Waterhen Fishermen’s Association, Skownan First Nation and other stakeholders/ resource users. This management plan provides a common understanding of the basic “concepts” for the sustainable management of the fisheries resource. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ………..…………………………………………………… Page 4 2. Fishery Objectives ………………………………………………............ Page 4 3. Priority of Allocation …..……………………………………………….. Page 5 4. Governance …………..…………………………………………………. Page 6 4.1 Legislative/Regulations/Policies …………………………………….… Page 6 4.2 Enforcement/Compliance ……………………………………………… Page 7 4.3 Precautionary Approach …………………………………………….... Page 7 5. Overview …………….…………………………………………………. Page 8 5.1 Location ……………………………………………………………….. Page 8 5.2 Participants …………..…………………………………………………. Page 8 5.2.1 Communities …………………………………………………….. Page 8 5.2.2 Sustenance ……………………………………………………… Page 9 5.2.3 Commercial Fishers ……..……………………………………... Page 9 5.2.4 Commercial Tourism ……………………………………………. Page 9 5.2.5 Recreational Anglers ……………………………………………. -

First Nations "! Lake Wasagamack P the Pas ! (# 297) Wasagamack First Nationp! ! ! Mosakahiken Cree Nation P! (# 299) Moose Lake St

102° W 99° W 96° W 93° W 90° W Tatinnai Lake FFiirrsstt NNaattiioonnss N NUNAVUT MMaanniittoobbaa N ° ° 0 0 6 6 Baralzon Lake Nueltin Kasmere Lake Lake Shannon Lake Nejanilini Lake Egenolf Munroe Lake Bain Lake Lake SASKATCHEWAN Northlands Denesuline First Nation (# 317) Shethanei Lake ! ! Sayisi Dene ! Churchill Lac Lac Brochet First Nation Brochet Tadoule (# 303) Lake Hudson Bay r e iv Barren Lands R (# 308) North ! Brochet Knife Lake l Big Sand il Etawney h Lake rc u Lake h C Buckland MANITOBA Lake Northern Southern Indian Lake Indian Lake N N ° ° 7 7 5 Barrington 5 Lake Gauer Lake Lynn Lake er ! Riv ! South Indian Lake n Marcel Colomb First Nation ! o O-Pipon-Na-Piwin Cree Nation ls (# 328) e (# 318) N Waskaiowaka Lake r Fox Lake e Granville Baldock v ! (# 305) i Lake Lake ! R s Leaf Rapids e Gillam y Tataskweyak Cree Nation a P! H (# 306) Rat P! War Lake Lake Split Lake First Nation (# 323) Shamattawa ! ! York Factory ! First Nation Mathias Colomb Ilford First Nation (# 304) York (# 307) (# 311) Landing ! P! Pukatawagan Shamattawa Nelson House P!" Thompson Nisichawayasihk " Cree Nation Partridge Crop (# 313) Lake Burntwood Lake Landing Lake Kississing Lake Atik Lake Setting Sipiwesk Semmens Lake Lake Lake Bunibonibee Cree Nation Snow Lake (# 301) Flin Flon ! P! Manto Sipi Cree Nation P! Oxford Oxford House (# 302) Reed Lake ! Lake Wekisko Lake Walker Lake ! God's ! Cross Lake Band of Indians God's Lake First Nation Lake (# 276) (# 296) !P Lawford Gods Lake Cormorant Hargrave Lake Lake Lake Narrows Molson Lake Red Sucker Lake N N (# 300) ° ° 4 ! Red Sucker Lake ! 4 Beaver 5 Hill Lake 5 Opaskwayak Cree Nation Norway House Cree Nation (# 315) Norway House P!! (# 278) Stevenson Garden Hill First Nations "! Lake Wasagamack P The Pas ! (# 297) Wasagamack First NationP! ! ! Mosakahiken Cree Nation P! (# 299) Moose Lake St. -

Planning Beyond the 7Th Generation

Planning Beyond the 7th Generation 2016/17 Annual Report * Approved by the Board of Directors of the First Nations Financial Management Board on July 25, 2017 “ Planning for 7 generations just isn’t enough—you need a system to support it” Chief Maureen Thomas, Tsleil-Waututh Nation, British Columbia Every First Nation has a past to honour, and a future to secure—a future fi lled with promise, where children thrive, communities grow and cultures prosper. That future could be tomorrow but planning for seven generations starts today. TABLE of CONTENTS Our Mission, Values and Mandate .................................................................................................................... 4 FMB at a Glance .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Message from the Executive Chair ...................................................................................................................... 6 Message from the A/Chief Operating Offi cer ................................................................................................. 7 Nipissing First Nation First in Ontario to Achieve FMS certifi cation ............................................... 8 FMB Clients (Map) .................................................................................................................................................... 10 FMB Board of Directors .......................................................................................................................................... -

Appendix D: Groups Included in Secondary Outreach Phase

Enbridge Pipelines Inc. Certificate OC-063 - Condition 12 Line 3 Replacement Program Aboriginal Monitoring Plan Appendix D Appendix D: Groups Included in Secondary Outreach Phase Agency Chiefs Tribal Council Mosquito Grizzly Bear's Head, Lean Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation Man First Nation Alexander First Nation Mountain Cree Asini Wachi Nehiyawak Alexis Nakota Sioux Nation Muscowpetung First Nation Assembly of First Nations Muskeg Lake Cree Nation Assembly of First Nations - Alberta Muskowekwan First Nation Region Nekaneet First Nation Assembly of First Nations - Manitoba O-Chi-Chak-ko-Sipi (Crane River) First Region Nation Assembly of First Nations - Ocean Man First Nation Saskatchewan Region Ochapowace First Nation Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs Okanese First Nation Battlefords Tribal Council One Arrow First Nation Battleford Agency Tribal Chiefs Onion Lake Cree Nation Beardy’s & Okemasis First Nation Papaschase First Nation Bearspaw First Nation Pasqua First Nation Beaver Lake Cree Nation Paul First Nation Big Island Lake Cree Nation Peepeekisis First Nation Big River First Nation Peguis First Nation Birdtail Sioux Dakota First Nation Pelican Lake Brokenhead Ojibway First Nation Pheasant Rump Nakota First Nation Buffalo Point First Nation Piapot First Nation Canupawakpa Dakota Nation Piikani Nation Carry the Kettle First Nation Pinaymootang First Nation Central Urban Métis Federation Inc. Pine Creek First Nation Chief Big Bear First Nation Poundmaker Cree Nation Chiniki First Nation Red Pheasant