The Digging Stick April 2021 Final.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE DIGGING STICK Volume 13, No

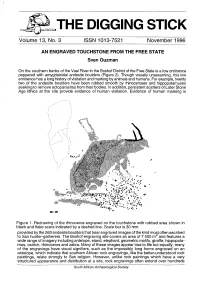

~_.THE DIGGING STICK Volume 13, No. 3 ISSN 1013-7521 November 1996 AN ENGRAVED TOUCHSTONE FROM THE FREE STATE Sven Ouzman On the southern banks of the Vaal River in the Boshof District of the Free State is a low eminence peppered with amygdaloidal andesite boulders (Figure 2). Though visually unassuming, this low eminence has a long history of visitation and marking by animals and humans. For example, twenty two of the andesite boulders have been rubbed smooth by rhinoceroses and hippopotamuses seeking to remove ectoparasites from their bodies. In addition, persistent scatters of Later Stone Age lithics at the site provide evidence of human visitation. Evidence of human marking is .... - - - ..... , \ \ \ I I I \ I \ I / \ / ' \ I I / ./' - / I/'\ / / /, \ I ( 1/ \ \ \ \ 1 \ \ \ \ / I \ \ If ~ I I 1-- - I I \ I I '\ : I \ I I \ 1/ \ // / '·f,···, \ / , \ / \ / I / \ / Figure 1. Redrawing of the rhinoceros engraved on the touchstone with rubbed area'shown in black and flake scars indicated by a dashed line. Scale bar is 30 mm. provided by the 263 andesite boulders that bear engraved images of the kind mo~t often ascribed to San hunter-gatherers. The Boshof engraving site covers an area of 7 500 m and features a wide range of imagery including antelope, eland, elephant, geometric motifs, giraffe, hippopota mus, ostrich, rhinoceros and zebra. Many of these images appear true to life but equally, many of the engravings have visual signifiers, such as the impossibly long horns engraved on an antelope, which indicate that southern African rock engravings, like the better-understood rock paintings, relate strongly to San religion. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Neolithic and chalcolithic cultures in Turkish Thrace Erdogu, Burcin How to cite: Erdogu, Burcin (2001) Neolithic and chalcolithic cultures in Turkish Thrace, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3994/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk NEOLITHIC AND CHALCOLITHIC CULTURES IN TURKISH THRACE Burcin Erdogu Thesis Submitted for Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. University of Durham Department of Archaeology 2001 Burcin Erdogu PhD Thesis NeoHthic and ChalcoHthic Cultures in Turkish Thrace ABSTRACT The subject of this thesis are the NeoHthic and ChalcoHthic cultures in Turkish Thrace. Turkish Thrace acts as a land bridge between the Balkans and Anatolia. -

The Digging Stick

- - -, THE DIGGING STICK Volume 6, No. 3 ISSN 1013-7521 November 1989 Rock engravings from the Bronze Age at Molteberg, landscape. There are two more pairs of feet to the right. south of Sarpsborg, N Olway. The engravings are found From a postcard published by Will Otnes, one of our on a horizontal rock overlooking an agricultural members who lives in Norway. (See also page 9.) South African Archaeological Society THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SETTING OF GENADENDAL, THE FIRST MISSION STATION IN SOUTH AFRICA A.J.B. HUMPHREYS Introduction monial threshold'. The period before the testimonial The mission station established in 1737 by George threshold falls entirely within the domain of archaeology Schmidt near what is today Genadendal has the distinc in that evidence of any events that occurred is recover tion of being the first such station in South Africa. Its able only through the use of archaeological techniques. purpose was, however, not simply to convert the local Once oral and written records begin to emerge, archaeo Khoikhoi to Christianity but, as Henry Bredekamp has logy becomes one of several different approaches to recently pointed out, Schmidt had as one of his primary studying the past of Genadendal. But despite the exist aims the complete religious and socio-economic trans ence of a testimonial record, archaeology can provide a formation of Khoikhoi society in that area. As Genaden dimension that would otherwise be lacking, particularly dal is situated within the region occupied by the Chain if the written portion of the record is the product of only oqua, Schmidt's efforts represent the first active Euro one of the parties involved in the interaction. -

300,000-Year-Old Wooden Tools from Gantangqing, Southwest China

300,000-year-old wooden tools from Gantangqing, southwest China Xing Gao ( [email protected] ) Chinese Academy of Sciences Jian-Hui Liu Yunnan Institute of Cultural Relics and Archeology Qi-Jun Ruan Yunnan Institute of Cultural Relics and Archeology Junyi Ge Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Beijing, 100044China https://orcid.org/0000-0002- 4569-2915 Yongjiang Huang Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academyof Sciences Jia Liu CAS Key Laboratory of Tropical Forest Ecology, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences Shufeng Li Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences Ying Guan Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Beijing, 100044China Hui Shen Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences Yuan Wang Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology Thomas Stidham Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences Chenglong Deng State Key Laboratory of Lithospheric Evolution, Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1848-3170 Shenghua Li Department of Earth Sciences, The University of Hong Kong Fei Han Yunnan University Page 1/19 Bo Li University of Wollongong https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4186-4828 Robin Dennell University of Exeter Biological Sciences - Article Keywords: Palaeolithic Wooden Implements, Digging Sticks, Sub-aquatic Plants, Sub-surface Plant Foods, Middle Pleistocene Posted Date: February 16th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-226285/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. -

![Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of Ethnology : [Bulletin]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3328/smithsonian-institution-bureau-of-ethnology-bulletin-1263328.webp)

Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of Ethnology : [Bulletin]

KM IT II SOX IAN J NSTITIITION BUREAU OF ETHNOLOGY: J. W. POWELL, DIRECTOR 11070 PERFORATED STONES C j± T, I F 1 OENIA HENRY VV. HENSHAW WASHINGTON GOTBRNIENT PRINTING OFFICE 188 7 CONTENTS Paso. General character and conjectural uses of perforated stones 5 Uses of perforated stones 7 Weights to digging (sticks in California «... 7 Digging s tides in various parts <>t the world 11 (Jan ling implements 16 Dies 18 Weights for nets 19 Spindle whorls 19 Club Leads 20 Stone axes 21 Ceremonial staves 22 Peruvian star shaped disks 26 Missiles 27 Stones with handles 28 Ceremonial implements .-. 30 Origin of perforated stones 32 Significance to the archaeologist of medicine practices • 34 ILLUSTRATIONS. Page. FlG. 1. Perforated stone, Santa Rosa Island, California 5 2. Perforated stone, Santa Cruz Island, California f< 3. Perforated stone, Santa Cruz Island, California (5 4. Perforated stones with incised lines, Southern California (i 5. Perforated stone with groove around perforal ion, Soul hern California. 10 (i. Supposed method of adjusting weight to digging stick 10 7. Supposed method of adjusting weight to digging stick It' 8. Hottentot- digging stick, after Burchell 12 9. Perforated stone from California, used in the game of itiirnrsh lii 10. Perforated stone used as a die, Santa Rosa- Island, California- 19 11. Ceremonial staff, New Guinea 24 12. Ceremonial staff, New Guinea 21 13. Star shaped disk mounted on handle, Peru 27 14. Perforated stone mounted on handle, Los Angeles Comity, California. 29 lf>. Perforated stone, mounted on handle, Los Angeles County, California.. 29 1<>. Perforated stone mounted on handle, Los Angeles County, California. -

Human Origin Sites and the World Heritage Convention in Eurasia

World Heritage papers41 HEADWORLD HERITAGES 4 Human Origin Sites and the World Heritage Convention in Eurasia VOLUME I In support of UNESCO’s 70th Anniversary Celebrations United Nations [ Cultural Organization Human Origin Sites and the World Heritage Convention in Eurasia Nuria Sanz, Editor General Coordinator of HEADS Programme on Human Evolution HEADS 4 VOLUME I Published in 2015 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France and the UNESCO Office in Mexico, Presidente Masaryk 526, Polanco, Miguel Hidalgo, 11550 Ciudad de Mexico, D.F., Mexico. © UNESCO 2015 ISBN 978-92-3-100107-9 This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/igo/). By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access Repository (http://www.unesco.org/open-access/terms-use-ccbysa-en). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Cover Photos: Top: Hohle Fels excavation. © Harry Vetter bottom (from left to right): Petroglyphs from Sikachi-Alyan rock art site. -

8. Conclusions

8. Conclusions 8.1 Introduction This chapter outlines the conclusions developed from the research results, discusses the implication of the findings and places them in the current framework of Australian rock art studies. The significance of this research to archaeological theory and to the practice of rock art studies is discussed. Issues that remain unresolved are identified and directions for future research are suggested. The results of the broader Change and Continuity research project are used to support an inclusive gendering analysis of the northwest Kimberley rock art. I have established that there are valid iconographic keys for gendering a portion of the anthropomorphic rock art figures devoid of sexual characteristics. The three periods, IIAP, Gwion and Wanjina all differ in this regard and will be discussed separately. Features identified as relevant are examined and those that have proved to be unreliable for sexing purposes are briefly discussed and discarded. A changing emphasis on anthropomorphic motifs in the rock art assemblage supports cultural change evident in the archaeological record. The successive art periods and the sexual focus related to human figures shows that the culture in the northwest Kimberley was not static through time. Rock art depictions of animal motifs and artefact representation offer a data set from which to develop a broader understanding of the demographic, economic and social structures. The relative stylistic sequence provides a comparative framework to identify trends associated with gendered roles in the culture through time. This has been achieved through analysis of the few sexed figures available in the data set complemented by a comparison with the unsexed figures with gendering features identified as accurate iconographic keys. -

Title How Hunter-Gatherers Have Learned to Hunt : Transmission Of

How Hunter-Gatherers Have Learned to Hunt : Transmission of Hunting Methods and Techniques among the Central Title Kalahari San (Natural History of Communication among the Central Kalahari San) Author(s) IMAMURA, Kaoru; AKIYAMA, Hiroyuki African study monographs. Supplementary issue (2016), 52: Citation 61-76 Issue Date 2016-03 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/207694 Right Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, Suppl. 52: 61–76, March 2016 61 How Hunter-gatherers Have Learned to Hunt: Transmission of Hunting Methods and TechniQues among the Central Kalahari San Kaoru IMAMURA Faculty of Contemporary Social Studies, Nagoya Gakuin University Hiroyuki AKIYAMA Faculty of Contemporary Home Economics, Kyoto Kacho University ABSTRACT In order to theorize about how hunting methods evolved around the time Nean- derthals was being replaced by anatomically modern Homo sapiens (AMH), the hunting meth- ods used by the San people-hunter-gatherers in the modern age—were studied in detail. As a result, it became clear that the San use a wide variety of methods to hunt small mammals and birds, in addition to using bows and spears to hunt large animals. It was also discovered that hunters included not only adult men, but also boys and adult women; boys in particular begin learning skills related to hunting and “reading nature” at the age of four or five. Taking an inter- est in animals and reading their minds through careful observation—an ability unique to mod- ern humans who are the only animals to possess this faculty—can be traced all the way back to the origins of the Homo sapiens. -

THE DIGGING STICK Volume 21, No 2 ISSN 1013-7521 August 2004

~ THE DIGGING STICK Volume 21, No 2 ISSN 1013-7521 August 2004 MARINE SHELL BEADS FROM 75 OOO-YEAR-OLD LEVELS AT BLOMBOS CAVE Christopher Henshilwood Blombos Cave (BBC), situated near Still Bay in turbed MSA deposits The five uppermost layers the southern Cape, lies some 100 m from the below BBC Hiatus are assigned to the M 1 phase coast and 35 m above sea level. The site was (see 'stratigraphy', p. 2), in which small basin discovered by the author in 1991 and initial shaped ash and carbon hearths are common. excavation of the Middle Stone Age (MSA) levels Carbonised sand and organic 'partings' a few was by him and Cedric Poggenpoel in 1992. millimetres thick act as visual markers for the Later his team of excavators included Judy separation of discrete occupation layers. M 1- Sealy, Royden Yates and Karen van Niekerk. phase lithics are typified by Still Bay- type bifacial foliate points. Two slabs of engraved ochre I bone The interior of the cave contains 55 m2 of visible tools and an en-graved bone came from this deposit with an estimated depth of ±4 to 5 m at phase, as reported in The Digging Stick (Hensh the front and ±3 m toward the rear. When excav ilwood 2002: 1). ations commenced in 1992 the cave entrance was almost totally sealed by dune sand and c. The magnificent group of Middle Stone Age beads 200 mmol-undisturbed aeelian sand everlay the found at Blombos Cave surface of the Later Stone Age (LSA), indicating no disturbance of the cave's contents since the final LSA occupation c. -

X:\Ventura8\Archsoc\Digging Stick\DS

THE DIGGING STICK Volume 34, No 1 ISSN 1013-7521 April 2017 THE KEY TO OUR FUTURE IS BURIED IN THE PAST Philosophical thoughts on saving us from ourselves Peter Nilssen and Craig Foster Imagine a world without fame, famine or fear, a world without waste, wars and mass extinction. Hard to imagine, and yet our ancestors lived in that world. Is it too much to imagine that we could get back to such a world? If we do not, then our future could be in serious doubt. If human behaviour is respon- sible for the current status of society and the quality of life on earth, and if archaeology investigates the development of human behaviour, then our discipline should be central to understanding the present and to guiding the future of our species and life on earth. Recreation – early human family crossing a lagoon on the South African south coast An abundance of scientific data shows that in the last few millennia humans have point, and if science is suggesting that we are at the placed life under severe stress and are expediting the end game, then we have answers to the why and sixth extinction event. It seems obvious then that the when. What remains unanswered is the how. How do thrust of current research should focus on securing our future. Archaeology can be a key player in that regard. If human behaviour has brought us to this OTHER FEATURES IN THIS ISSUE Dr Peter Nilssen is a professional archaeologist of 30 years’ experience and now specialises in communicating archaeology for 7 Stories and myths about the pre-Iron education and conservation. -

Western and Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Ecocultural Restoration Joy B

OCTOBER 2018 RESEARCH Western and Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Ecocultural Restoration Joy B. Zedler1 and Michelle L. Stevens2 TEK adds culturally-significant species to restoration Volume 16, Issue 3 | Article 2 https://doi.org/10.15447/sfews.2018v16iss3art2 targets and traditional management practices to achieve ecological resilience. We compare 11 * Corresponding author: [email protected] attributes of WEK and TEK that aid ecological 1 University of Wisconsin, Madison restoration; all are complementary or shared by these Madison, WI 53706 USA two ways of knowing. Both WEK and TEK emphasize 2 California State University, Sacramento Sacramento, CA 95819 USA adaptive approaches for managing natural resources, as mandated in the Delta Plan. We suggest that WEK–TEK restoration sites throughout the Delta can be linked (virtually) to honor cultural integrity and ABSTRACT nurture a “Sense of Place” for Native Californians and others. At the same time, such a network could The Delta Plan (DSC 2013) calls for “protecting foster ways to achieve sustainability through the TEK and enhancing the unique cultural values” of ethic of reciprocity, which WEK lacks. A network of California’s Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta, a WEK–TEK sites could enhance unique cultural values 2,800-km2 (1,100 mi2) region that was occupied by while supporting passive recreation and attracting indigenous peoples for ~5,000 years. The legacies of ecotourists. Native Californians need to be included in the Delta Plan, especially Traditional Ecological Knowledge KEY WORDS (TEK) of ways to gather, hunt, and fish for food; build shelters; prepare medicines; and perform Adaptive Management, Native Californian, ceremonies — along with ways to make tools, clothing, reciprocity, restoration, Sacramento–San Joaquin baskets, and shelters. -

The Continuing Lessons of Band Level Societies

Mississippi Valley Archaeology Center 1725 State Street La Crosse, Wisconsin 54601 Phone: 608-785-6473 Web site: http://www.uwlax.edu/mvac/ The following lessons were created by Judd Lefeber, a teacher participating in the National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Institute for Teachers entitled Touch the Past: Archaeology of the Upper Mississippi River Region. Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities. The Continuing Lessons of Band Level Societies Grade Level 11-12 Grade Subjects Sociology, Anthropology, or World History Objectives By the end of this lesson/mini-unit, students will be able to analyze hunter-gatherer artifacts to discern the salient aspects of hunter-gatherer and band level societies describe the common characteristics of hunter-gatherer and band-level societies explain four of the components of culture (subsistence pattern, social organization, settlement type, and ideology) compare and contrast hunter-gatherer (band-level) social organizations, settlement type, and possible common ideologies to those of our current society Standards WI Social Studies Standards E.12.4 Analyze the role of economic, political, educational, familial, and religious institutions as agents of both continuity and change, citing current and past examples E.12.5 Describe the ways cultural and social groups are defined and how they have changed over time E.12.6 Analyze the means by which and extent to which groups and