Tierra Del Fuego

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Satellite-Derived Volume Loss Rates and Glacier Speeds for the Cordillera Darwin Title Page Icefield, Chile Abstract Introduction Conclusions References 1 1 1 2,3 2 A

Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | The Cryosphere Discuss., 6, 3503–3538, 2012 www.the-cryosphere-discuss.net/6/3503/2012/ The Cryosphere doi:10.5194/tcd-6-3503-2012 Discussions TCD © Author(s) 2012. CC Attribution 3.0 License. 6, 3503–3538, 2012 This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal The Cryosphere (TC). Satellite-Derived Please refer to the corresponding final paper in TC if available. Volume Loss Rates A. K. Melkonian et al. Satellite-Derived Volume Loss Rates and Glacier Speeds for the Cordillera Darwin Title Page Icefield, Chile Abstract Introduction Conclusions References 1 1 1 2,3 2 A. K. Melkonian , M. J. Willis , M. E. Pritchard , A. Rivera , F. Bown , and Tables Figures S. A. Bernstein4 1Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, USA J I 2Centro de Estudios Cient´ıficos (CECs), Valdivia, Chile J I 3Departamento de Geograf´ıa, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile 4St. Timothy’s School, 8400 Greenspring Ave, Stevenson, MD, 21153, USA Back Close Received: 12 July 2012 – Accepted: 31 July 2012 – Published: 31 August 2012 Full Screen / Esc Correspondence to: A. K. Melkonian ([email protected]) Printer-friendly Version Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. Interactive Discussion 3503 Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Abstract TCD We produce the first icefield-wide volume change rate and glacier velocity estimates for the Cordillera Darwin Icefield (CDI), a 2605 km2 temperate icefield in Southern Chile 6, 3503–3538, 2012 (69.6◦ W, 54.6◦ S). Velocities are measured from optical and radar imagery between 5 2001–2011. -

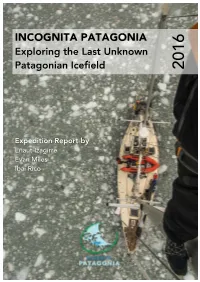

INCOGNITA PATAGONIA Exploring the Last Unknown

INCOGNITA PATAGONIA Exploring the Last Unknown Patagonian Icefield 2016 Expedition Report by Eñaut Izagirre Evan Miles Ibai Rico EXPEDITION REPORT INCOGNITA PATAGONIA: Exploring the Last Unknown Patagonian Icefield An exploratory and glaciological research expedition to the Cloue Icefield of Hoste Island, Tierra del Fuego, Chile in March-April 2016. Eñaut Izagirre* Evan Miles Ibai Rico *Correspondence to: [email protected] Dirección de Programas Antárticos y Subantárticos Universidad de Magallanes 2016 This unpublished report contains initial observations and preliminary conclusions. It is not to be cited without the written permission of the team members. Incognita Patagonia returns from Tierra del Fuego with an improved understanding of the region's glacial history and an appreciation for adventure in terra incognita, having traversed the Cloue Icefield and ascended two previously unclimbed peaks. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INCOGNITA PATAGONIA sought to explore and document the Cloue Icefield on Hoste Island, Tierra del Fuego, Chile, with a focus on observing the icefield's glaciers to develop a chronology of glacier change and associated landforms (Figure 1). We were able to achieve all of our primary observational and exploratory objectives in spite of significant logistical challenges due to the fickle Patagonian weather. Our team first completed a West-East traverse of the icefield in very difficult conditions. We later returned to the glacial plateau with better weather and completed a survey of the major mountains of the plateau, validating two peaks' summit elevations. At the glaciers' margins, we mapped a series of moraines of various ages, including very fresh moraines from recent glacial advances. One glacier showed a well-preserved set of landforms indicating a recent glacial lake outburst flood (GLOF), and we surveyed and dated these features. -

Satellite-Derived Volume Loss Rates and Glacier Speeds for the Cordillera Darwin Icefield, Chile

EGU Journal Logos (RGB) Open Access Open Access Open Access Advances in Annales Nonlinear Processes Geosciences Geophysicae in Geophysics Open Access Open Access Natural Hazards Natural Hazards and Earth System and Earth System Sciences Sciences Discussions Open Access Open Access Atmospheric Atmospheric Chemistry Chemistry and Physics and Physics Discussions Open Access Open Access Atmospheric Atmospheric Measurement Measurement Techniques Techniques Discussions Open Access Open Access Biogeosciences Biogeosciences Discussions Open Access Open Access Climate Climate of the Past of the Past Discussions Open Access Open Access Earth System Earth System Dynamics Dynamics Discussions Open Access Geoscientific Geoscientific Open Access Instrumentation Instrumentation Methods and Methods and Data Systems Data Systems Discussions Open Access Open Access Geoscientific Geoscientific Model Development Model Development Discussions Open Access Open Access Hydrology and Hydrology and Earth System Earth System Sciences Sciences Discussions Open Access Open Access Ocean Science Ocean Science Discussions Open Access Open Access Solid Earth Solid Earth Discussions The Cryosphere, 7, 823–839, 2013 Open Access Open Access www.the-cryosphere.net/7/823/2013/ The Cryosphere doi:10.5194/tc-7-823-2013 The Cryosphere Discussions © Author(s) 2013. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Satellite-derived volume loss rates and glacier speeds for the Cordillera Darwin Icefield, Chile A. K. Melkonian1, M. J. Willis1, M. E. Pritchard1, A. Rivera2,3, F. Bown2, and S. A. Bernstein4 1Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, USA 2Centro de Estudios Cient´ıficos (CECs), Valdivia, Chile 3Departamento de Geograf´ıa, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile 4St. Timothy’s School, 8400 Greenspring Ave, Stevenson, MD 21153, USA Correspondence to: A. -

Little Ice Age and Recent Glacier Advances in the Cordillera Darwin, Tierra Del Fuego, Chile

Anales Instituto Patagonia (Chile), 2015. Vol. 43(1):127-136 127 Little Ice Age and recent glacier advances in the Cordillera Darwin, Tierra del Fuego, Chile Pequeña Edad de Hielo y los avances recientes en los glaciares de la Cordillera Darwin, Tierra del Fuego, Chile Johannes Koch1 Abstract investigaciones previas postulan que los glaciares Preliminary fieldwork provides evidence for glacier de la Cordillera Darwin no avanzaron durante advances in the Cordillera Darwin during the la “clásica” Pequeña Edad del Hielo, sino que lo ‘classic’ Little Ice Age as well as in the late 20th and hicieron antes de ésta. El presente estudio indica que the early 21st centuries. Little Ice Age advances have los glaciares en la Cordillera Darwin probablemente been reported at nearby sites in the Patagonian siguieron una cronología Pequeña Edad de Hielo Andes, but previous research claimed that glaciers similar a la mayoría de los glaciares en los Andes of the Cordillera Darwin did not advance during Patagónicos. Avances recientes de glaciares de ‘classic’ Little Ice Age time, but earlier. The present sobre 1.5 km son respaldados por trabajos previos. study indicates that glaciers in the Cordillera Darwin Las razones para estos avances permanecen sin likely followed a similar Little Ice Age chronology as clarificar, especialmente ante las claras tendencias al most glaciers in the Patagonian Andes. The recent calentamiento en el sur de Sud América en los siglos glacier advances of over 1.5 km are supported 20 e inicios del 21. Sin embargo, en forma similar a by previous work. The reason for these advances glaciares en Noruega y Nueva Zelandia que también remains unclear, especially as clear warming trends avanzaron a finales del siglo 20, la intensidad de are observed in southern South America in the la circulación atmosférica del oeste ha aumentado 20th and early 21st centuries. -

Universidad De Chile Facultad De Ciencias Físicas Y Matemáticas Departamento De Geología

UNIVERSIDAD DE CHILE FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS FÍSICAS Y MATEMÁTICAS DEPARTAMENTO DE GEOLOGÍA INSIGHTS ON THE HOLOCENE CLIMATE OF SOUTHERNMOST SOUTH AMERICA FROM PALEOGLACIER RECONSTRUCTIONS IN PATAGONIA AND TIERRA DEL FUEGO (46°-55°S) TESIS PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE DOCTOR EN CIENCIAS MENCIÓN GEOLOGÍA SCOTT ANDREW, REYNHOUT PROFESOR GUÍA: MAISA ROJAS CORRADI MIEMBROS DE LA COMISIÓN: VALENTINA FLORES AQUEVEQUE MICHAEL KAPLAN ESTEBAN SAGREDO TAPIA GABRIEL VARGAS EASTON SANTIAGO DE CHILE 2019 RESUMEN DE LA TESIS PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE: Doctor en Ciencias, mención Geología POR: Scott Andrew Reynhout Reynhout FECHA: 03/09/2019 PROFESOR GUIA: Maisa Rojas Corradi “INSIGHTS ON THE HOLOCENE CLIMATE OF SOUTHERNMOST SOUTH AMERICA FROM PALEOGLACIER RECONSTRUCTIONS IN PATAGONIA AND TIERRA DEL FUEGO (46°-55°S)” This dissertation presents preliminary and final results of four paleoglacier reconstructions in the regions of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego (46°-55°S), with the objective of identifying trends in Holocene climate in southernmost South America. Two complete chronologies and one partial chronology of Holocene glacier fluctuations are determined by geomorphologic mapping, cosmogenic surface exposure dating of glacial landforms, dendroglaciology, and radiocarbon dating. Former glacier surfaces from four sites across the region are reconstructed to evaluate spatial variability of equilibrium-line altitude depression associated with age-constrained glacier advances. Glaciar Torre (Chapter 3; 49.3°S / 73.0°W) advanced to pre-Holocene maxima at c. 17 ka and c. 13 ka, coincident with the onset of the Last Glacial Termination and the end of the Antarctic Cold Reversal, respectively. While the record at the Dalla Vedova glacier (Chapter 4; 54.6°S / 69.1°W) is less well-constrained, the few dates available suggest potentially synchronous advances occurred at these times. -

Río Gallegos

R www.elviajeroweb.com Tu compañero de viaje en la Patagonia... edición 07, diciembre 2014 edición 07, diciembre llévala contigo!! - Take it with you !! Síguenos en Facebook y Twitter El Viajero / 03 2 Gerencia Comercial Traducción Articulos: Mariano Silva María Soledad Solís cel:(56-9) 53643587 ÍNDICE INDEX Producción y diseño: Romina Warner Juegos: Information Puerto Natales 06 Information Puerto Natales 06 Fernando Molina Fotografía Portada: Information Punta Arenas 08 Information Punta Arenas 08 Alfredo Soto Ventas y Distribución: Información Torres del Paine 10 Information Torres del Paine 08 Griseida Mata Mapa torres del Paine: [email protected] Mapa Torres del Paine 10 Torres del Pine Maps 10 CONAF cel: (56) 9 54157584 Información Río Gallegos 14 Information Río Gallegos 14 Artículo Aventura Alfredo Soto Información El Calafate 16 Information El Calafate 16 Articulo Fauna Información Ushuaia 18 Information Ushuaia 18 Alfredo Soto Guía de Servicios 21 Services Guide 21 Opinion Austral Solución Gerardo Rosales Aventura Austral 28 Austral Adventure 28 Puzzle Juegos 32 Games 32 Fotografías Interior: Alfredo Soto Destino Recomendado 36 Recommended Destination 36 Sonia Barrientos Griseida Mata Sabor de la Patagonia 38 Patagonia Flavour 38 Patricia Andrade Jorge Gonzalez Fauna de la Patagonia 40 Patagonic Fauna 40 Ana María Pérez Romina Warner Eventos 45 Events 45 Erling Johnson Opinión Austral 46 “Opinión Austral” 46 Carolina Henriquez Severino 1 El Viajero / 04 Tu compañero de viaje en la Patagonia... R www.elviajeroweb.com Tu -

Taken from Mountaineering in the Andes by Jill Neate Tierra Del Fuego RGS-IBG Expedition Advisory Centre, 2Nd Edition, May 1994

Taken from Mountaineering in the Andes by Jill Neate Tierra Del Fuego RGS-IBG Expedition Advisory Centre, 2nd edition, May 1994 TIERRA DEL FUEGO Map showing Tierra Del Fuego The numerous channels between the islands of this archipelago at the southern extremity of South America subdivide the region into three distinct sections - Isla Grande, the principal land mass, delimited to the north by Magellan’s Strait and to the south by the Beagle Channel; the islands to the south of the Beagle Channel; and the islands, notably Santa In‚s, lying west of Magellan’s Strait and north of the Magdalena-Cockburn Channels. The principal mountain masses are situated in the south-west part of Isla Grande and from west to east are - Sarmiento; Buckland and Cordòn Sella; Cordòn Navarro; Cordillera Darwin; Monte Olivia; and Cordòn Alvear, north-east of Ushuaia. Battered perennially by icy winds and touched by cold Antarctic currents the mountains of Tierra del Fuego are heavily glaciated. These glaciers fall in places to sea-level, particularly in the Cordillera Darwin where deep fiords penetrate the heart of the mountain massifs. Charles Darwin recorded his astonishment when he first saw a range of only 1000 metres in height ‘with every valley filled with streams of ice descending to the sea-coast. Great masses of ice frequently fall from these icy cliffs, and the crash reverberates like the broadside of a man of war through the lonely channels’. Over the years a few hydrographers climbed small coastal hills and recorded information about high mountain ranges and important summits lying near the coasts.