Abc-19 Rapid Test

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COVID-19: Make It the Last Pandemic

COVID-19: Make it the Last Pandemic Disclaimer: The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city of area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Report Design: Michelle Hopgood, Toronto, Canada Icon Illustrator: Janet McLeod Wortel Maps: Taylor Blake COVID-19: Make it the Last Pandemic by The Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness & Response 2 of 86 Contents Preface 4 Abbreviations 6 1. Introduction 8 2. The devastating reality of the COVID-19 pandemic 10 3. The Panel’s call for immediate actions to stop the COVID-19 pandemic 12 4. What happened, what we’ve learned and what needs to change 15 4.1 Before the pandemic — the failure to take preparation seriously 15 4.2 A virus moving faster than the surveillance and alert system 21 4.2.1 The first reported cases 22 4.2.2 The declaration of a public health emergency of international concern 24 4.2.3 Two worlds at different speeds 26 4.3 Early responses lacked urgency and effectiveness 28 4.3.1 Successful countries were proactive, unsuccessful ones denied and delayed 31 4.3.2 The crisis in supplies 33 4.3.3 Lessons to be learnt from the early response 36 4.4 The failure to sustain the response in the face of the crisis 38 4.4.1 National health systems under enormous stress 38 4.4.2 Jobs at risk 38 4.4.3 Vaccine nationalism 41 5. -

The Companion Test to SARS-Cov-2 Vaccination Innovating Rapid Testing to Preserve and Improve Life

TM The companion test to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination Innovating rapid testing to preserve and improve life Innovating rapid testing to preserve and improve life Leading the UK RTC Contents Introduction Page 03 The nature of SARS-CoV-2 testing has changed. Where Currently available tests detect antibodies targeting antibody tests were once chiefly used for charting the two different proteins on the SARS-CoV-2 virus: Introduction spread of infection within communities, today it is the Nucleocapsid or the Spike protein. However, almost 04 emerging as a key pillar of large-scale immunisation without exception, vaccine formulations are based on campaigns. the Spike protein. Vaccines and antibody tests converge on the same target However, there are stark differences between currently Testing for Nucleocapsid protein antibodies alone is 05 available antibody tests in both function and form. therefore of limited value. Though they may seem technical, these factors have Emerging evidence links prior infection with SARS-CoV-2 with immunity This short paper explains how rapid antibody testing significant implications for immunisation policy going focused on detecting the antibody response to the Spike 06 forward. protein, working hand in hand with vaccination, can help AbC-19™ Rapid Test The crucial difference is the antibody response that populations accelerate to herd immunity to SARS-CoV-2.. 06 the tests are evaluating. Trial of AbC-19™ Rapid Test with Vaccines 08 Summary 10 Contact 12 References 02 The companion test to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination 03 Vaccines and antibody tests Emerging evidence links prior infection converge on the same target with SARS-CoV-2 with immunity The SARS-CoV-2 virus comprises a single strand of RNA As a result, vaccine research has focused overwhelmingly on Two questions have dogged researchers since the outbreak of enveloped within four structural proteins. -

Dear Rook Irwin Sweeney Good Law Project Limited V Secretary of State

Rook Irwin Sweeney LLP Our ref: SS/335/10241.0086 107-111 Fleet Street Your ref: AMI:AIR;162 London EC4A 2AB 4 May 2021 By email: Dear Rook Irwin Sweeney Good Law Project Limited v Secretary of State for Health and Social Care v Abingdon Health Limited As you are aware, Abingdon Health plc (“Abingdon”) has not yet decided whether to participate in the judicial review proceedings that the Good Law Project (“GLP”) have brought against the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, in which Abingdon is named as an Interested Party. Our client acknowledges the GLP’s right to challenge the Department of Health and Social Care’s (“DHSC’s”) processes, but is concerned about the basis on which the case is proceeding. Therefore, we would like to set out some points of clarification below, and have enclosed documents that we hope are useful. The test developed by Abingdon that is the subject of these proceedings is referred to as the “AbC-19TM Test”. Abingdon Health and its expertise 1. Throughout the proceedings to date, the GLP has made multiple disparaging statements about Abingdon’s expertise and its ability to develop a COVID-19 antibody test.1 Such statements have led the Court to conclude that “the extent to which Abingdon Health itself had any expertise is open to serious doubt”.2 In our view, there is no doubt at all as to Abingdon’s expertise, and it was eminently qualified for the task of developing a COVID-19 antibody test. On a full analysis of the facts, a Court would be likely to conclude the same. -

Whole Blood-Based Measurement of SARS-Cov-2-Specific T Cell

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.02.21258218; this version posted June 3, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . Whole blood-based measurement of SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell responses reveals asymptomatic infection and vaccine efficacy in healthy subjects and patients with solid organ cancers Martin J. Scurr1,2, Wioleta M. Zelek3,4, George Lippiatt2, Michelle Somerville1, Stephanie E. A. Burnell1, Lorenzo Capitani1, Kate Davies5, Helen Lawton5, Thomas Tozer6, Tara Rees6, Kerry Roberts6, Mererid Evans7, Amanda Jackson7, Charlotte Young7, Lucy Fairclough8, Mark Wills9, Andrew D. Westwell10, B. Paul Morgan3,4, Awen Gallimore*1,3§ and Andrew Godkin*1,3,6§ 1 Division of Infection & Immunity, School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK. 2 ImmunoServ Ltd., Cardiff, UK 3 Systems Immunity University Research Institute, School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK. 4 UK Dementia Research Institute Cardiff, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK. 5 Radyr Medical Centre, Cardiff, UK. 6 Dept. of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, University Hospital of Wales, Heath Park, Cardiff, UK. 7 Velindre Cancer Centre, Cardiff, UK. 8 School of Life Sciences, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK. 9 Department of Medicine, Addenbrookes Hospital, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. 10 School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK. * Corresponding Authors: Prof Andrew Godkin Division of Infection and Immunity Henry Wellcome Building Health Park Cardiff CF14 4XN Email: [email protected] Authorship note: (§) Aw.G and An.G contributed equally to this work. -

Data Science and AI in the Age of COVID-19

Data science and AI in the age of COVID-19 Reflections on the response of the UK’s data science and AI community to the COVID-19 pandemic Executive summary Contents This report summarises the findings of a science activity during the pandemic. The Foreword 4 series of workshops carried out by The Alan message was clear: better data would Turing Institute, the UK’s national institute enable a better response. Preface 5 for data science and artificial intelligence (AI), in late 2020 following the 'AI and data Third, issues of inequality and exclusion related to data science and AI arose during 1. Spotlighting contributions from the data science 7 science in the age of COVID-19' conference. and AI community The aim of the workshops was to capture the pandemic. These included concerns about inadequate representation of minority the successes and challenges experienced + The Turing's response to COVID-19 10 by the UK’s data science and AI community groups in data, and low engagement with during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the these groups, which could bias research 2. Data access and standardisation 12 community’s suggestions for how these and policy decisions. Workshop participants challenges might be tackled. also raised concerns about inequalities 3. Inequality and exclusion 14 in the ease with which researchers could Four key themes emerged from the access data, and about a lack of diversity 4. Communication 17 workshops. within the research community (and the potential impacts of this). 5. Conclusions 20 First, the community made many contributions to the UK’s response to Fourth, communication difficulties Appendix A. -

Wetherspoon-News-Do-Lockdowns-Work-Winter-2020.Pdf

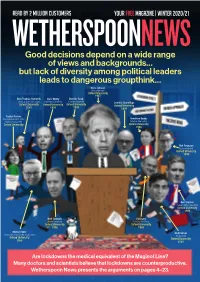

READ BY 2 MILLION CUSTOMERS your free magazine | winter 2020/21 WETHERSPOONNEWS Good decisions depend on a wide range of views and backgrounds… but lack of diversity among political leaders leads to dangerous groupthink… Boris Johnson (Prime Minister) Oxford University 1987 Nick Thomas-Symonds Chris Whitty Dominic Raab (Shadow Home Secretary) (Chief Medical Officer) (Foreign Secretary) Dominic Cummings Oxford University Oxford University Oxford University Oxford University 2001 1991 1993 1994 Rachel Reeves (Shadow Chancellor of the Anneliese Dodds Duchy of Lancaster) (Shadow Chancellor) Oxford University Oxford University 1998 Neil Ferguson (epidemiologist) Oxford University 1990 Keir Starmer (Leader of the Opposition) Oxford University 1986 Matt Hancock Ed Davey (Health Secretary) (Leader, Lib Dems) Oxford University Oxford University 1996 1988 Michael Gove Rishi Sunak (Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster) (Chancellor) Oxford University Oxford University 1988 2001 Are lockdowns the medical equivalent of the Maginot Line? Many doctors and scientists believe that lockdowns are counterproductive. Wetherspoon News presents the arguments on pages 4–23. Tim’s Viewpoint Weak leaders follow the crowd – only the brave will stand alone Politicians have become disciples of failed forecasters – and continue to promote lockdowns Johan Giesecke, the ‘Great Recession’ of 2008– country’s highest-paid economy and to mental Swedish epidemiologist, 10 is a fairly recent example. journalist as a young man, and physical health. said in April (interview No sector of the economy then a renowned historian – In addition, as former on page 14) that it was comprises more top-class and, against the odds, rallied Supreme Court judge “fascinating” how deeply university graduates than the country in its darkest hour Jonathan Sumption flawed Imperial College the banks, brokers and fund to battle for survival. -

“£18Bn Spent on Opaque Covid Contracts”

this week WOBBLE ROOMS page 297 • POPULATION TESTING page 298 • INFANT FORMULA page 300 FINNBARR WEBSTER/GETTYIMAGES “£18bn spent on opaque covid contracts” The government failed to provide Personal protective equipment accounted The government awarded transparency when hastily awarding for 80% of the contracts awarded (more contracts worth a total of billions of pounds’ worth of contracts during than 6900) and 68% of the total value £12.3bn to PPE suppliers, the pandemic, the UK’s public spending (£12.3bn) . The DHSC awarded £1.5bn many without a competitive tender process watchdog has concluded. worth of contracts to 71 suppliers, before The National Audit Offi ce said that there its process to assess applications was was also inadequate documentation on how standardised, the NAO found. the government had reached key decisions, The government also established a including why suppliers were chosen or “high priority lane” to assess potential PPE how potential confl icts of interest had been sources referred by offi cials and politicians handled. that were deemed more credible. About one The investigation found that the in 10 suppliers processed through this lane government awarded more than 8600 (47 of 493) obtained contracts, compared contracts worth £18bn by 31 July, with with less than one in 100 in the ordinary LATEST ONLINE most (worth £16.2bn) awarded by the lane (104 of 14 892). The NAO also found Innova lateral flow Department of Health and Social Care that sources of referrals to the high priority test is not fi t for (DHSC) and its national bodies. Contracts lane were not always documented. -

R01hosei Coronavirus.Pdf

令和 2 年度内閣官房健康・医療戦略室請負業務 令和 2 年度 新型コロナウイルス感染症等の新興感染症 に対する研究開発についての調査 調査報告書 令和 3 年 3 ⽉ デロイト トーマツ コンサルティング合同会社 ⽬次 本編 1. 調査概要 p. 3 2. 必要機能の全体像 p. 8 3. 他国及び⽇本における新興感染症への平時の取組み P. 11 3-1. 概要 p. 13 3-2. 詳細 3-2-1. 政府 P. 20 3-2-2. 国際機関 P. 49 3-2-3. アカデミア及び企業 P. 51 3-3. 他国からの学び P. 55 4. 他国及び⽇本における新型コロナウイルス感染症への緊急時の取組み P. 57 4-1. 概要及び新型コロナウイルス感染症の研究開発成果 P. 59 4-2. 詳細 4-2-1. 政府 P. 64 4-2-2. 国際機関 P. 88 4-2-3. アカデミア及び企業 p. 90 4-3. 他国からの学び P. 101 5. 成果創出に向けて必要な機能と⽬指す⽔準 P. 104 5-1. 各機能において具備すべき⽔準 P. 106 5-2. 各機能における他国と我が国の現状 P. 110 5-3. ⽬指す⽔準の実現に向けた政策アイディア P. 127 付録 A. 略語 P. 133 ・弊社は、貴室と弊社との間で締結された2020年11⽉4⽇付けの請負契約書に基づき、貴室と事前 に合意した⼿続きを実施しました。本報告書は、上記⼿続きに従って、貴室の政策策定の参考資料 として作成されたもので、内容の採否や使⽤⽅法については、貴室⾃らの責任で判断を⾏うものと します。 ・本報告書に記載されている情報は、公開情報を除き、調査対象会社から提出を受けた資料、また、 その内容についての質問を基礎としております。これら対象会社から⼊⼿した情報⾃体の妥当性・ 正確性については、弊社側で責任を持ちません。 ・本報告書における分析⼿法は、多様なものがありうる中でのひとつを採⽤したに過ぎず、その達 成可能性に関して、弊社がいかなる保証を与えるものではありません。本報告書が本来の⽬的以外 に利⽤されたり、第三者がこれに依拠したとしても弊社はその責任を負いません。 1 2 1. 調査概要 3 調査の背景と⽬的 新興感染症に対して、新型コロナウイルス感染症に関する対応に加え、平時か らの各国の対応・体制を把握し、今後の検討の⼀助とする 背景・⽬的 健康・医療戦略で掲げている、健康⻑寿社会の形成に資する重要な取組として、 新型コロナウイルス感染症対策の推進において、必要な研究開発等の対策を速や かに推進することとされている 今回の新型コロナウイルス感染症の拡⼤では、緊急に既存抗ウイルス薬の適⽤拡 ⼤の臨床試験を実施するなど、柔軟な対応が実施されたが、今後も同様の問題が ⽣じる可能性は想定され、平時より、新規感染症が発⽣した場合に、速やかに予 防・治療に必要な医薬品を開発・供給するためルール・体制の整備が求められる その為、本調査を平時より整備しておくべき研究開発体制や有事に即時に対応で きる研究開発プラットフォームの構築検討を推進するための基本資料とする 調査内容 本調査では、以下の調査・分析を実施している 1. 新興感染症の発⽣時の研究開発に必要な機能の特定 2. 諸外国における診断法、治療薬、ワクチン開発に必要な機能の 整備体制 • 新型コロナウイルス感染症に対する研究開発経緯・進捗状況 • 診断法、治療薬、ワクチンの研究開発に関わる必要な機能の体制整備 • 平時の事前準備状況 • 新興感染症等の有事における政策 • 産学官の役割分担や連携 3. -

Covid-19: Screening Without Scrutiny, Spending Taxpayers' Billions

EDITOR'S CHOICE BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj.m4487 on 19 November 2020. Downloaded from The BMJ [email protected] Follow Kamran on Covid-19: Screening without scrutiny, spending taxpayers’ billions Twitter @KamranAbbasi Kamran Abbasi executive editor Cite this as: BMJ 2020;371:m4487 http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4487 Mass testing is a euphemism for population with a track record of maladministration. Among Published: 19 November 2020 screening. A range of experts who care about these failures, perhaps the gravest error is an arrogant screening for the right reasons, in the right contexts, disregard for scrutiny. with the right tests, and with the correct follow-up, 1 Gill M, Gray M. Mass testing for covid-19 in the UK. BMJ 2020;371:m4436. are in no doubt. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4436 pmid: 33199289 Mike Gill and Muir Gray (who was knighted for his 2 Iacobucci G, Coombes R. Covid-19: Government plans to spend £100bn on expanding testing to 10 million a day. BMJ 2020;370:m3520. work on national screening programmes) insist the doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3520 pmid: 32907851 1 Liverpool mass testing pilot must be stopped. It is 3 Raffle AE. Screening the healthy population for covid-19 is of unknown screening by the back door, bypassing appraisal by value, but is being introduced nationwide. BMJ 2020;371:m4438. the UK’s National Screening Committee. The lateral 4 Jones B, Czauderna J, Redgrave P. We must stop being polite about Test flow test being used is of doubtful value, with a high and Trace—there comes a point where it becomes culpable. -

Annual Report 2020–21 Annual Report 2020–21

Annual Report 2020–21 Annual Report 2020–21 Section 1 3 An exceptional year Section 2 65 Trustees’ and strategic report Section 3 89 Financial statements Section 1 An exceptional year 1.1 Chair’s report 4 1.2 Institute Director’s report 6 1.3 Equality, diversity and inclusion 9 1.4 Partnerships and collaborations 12 1.5 Research highlights of the year 19 1.6 The Turing’s response to COVID-19 36 1.7 The year in numbers 43 1.8 Engagement, outreach and skills 48 3 Section 1.1 Chair’s report The work of our data science and AI Quaisr, with its own approach to digital twin community, alongside our partners in technology. industry, third sector and government, This has been an especially testing time for has once again been evident across many the higher education sector and I particularly domains. This sense of collaboration was wish to thank our network of universities for demonstrated at our highly successful first their support. This year we have seen two national showcase AI UK. You will see in universities running Data Study Groups in this year’s annual report examples of how collaboration with the Institute. The launch the Institute is collaborating by predicting of a new research showcase series that sea ice loss, mapping the UK’s solar panels, engages partners from across our network, and even developing underground farms. and the rapid growth of our interest groups, The Alan Turing Institute has also been are both powerful examples of the Institute’s proud to play its part in the response to the ability to convene and connect some of the devastating COVID-19 pandemic. -

Update on Innovation in Testing and Pillars 3&4 of the National Testing

, Webinar: Update on Innovation in Testing and Pillars 3&4 of the National Testing Strategy Our National Effort for Diagnostics Lord Bethell of Romford Parliamentary Under Secretary of State, Department of Health and Social Care 2 Today’s Agenda 13:10- 13:25 Update on Pillar 3 – Tim Brown, Director, COVID-19 Response: Antibody Testing Strategic Update and Forward Look Update on Pillar 4 – John Hatwell, Director, COVID-19 Response; Paul Elliott, Chair in Epidemiology and Public Health Medicine at Imperial College London Q&A 13:25-13:45 Triage and Evaluation System- Dan Bamford, Deputy Director COVID-19 Testing Programme (New Tests) Triage and Evaluation System Q&A 13:45-14:15 Diagnostics Innovation Team – Piers Ricketts, SRO Diagnostics Innovations Team; Anna Dijkstra, COVID-19 Testing Diagnostics Innovation Team Supply Q&A 14:15-14:25 Update on Point of Care Tests – Lindsey Hughes, Deputy Director and Lead for COVID-19 Testing Supplies Novel New Crowdsourcing Challenges Solutions Team Latest challenge/s and update on the previous challenges – Doris Ann Williams, CEO BIVDA 14:25-14:30 Doris-Ann Williams, Chief Executive of BIVDA Close 3 Update on Pillar 3 Tim Brown, Director, COVID-19 Response: Antibody Testing 4 Our National Testing Strategy ‘Pillar 1’ : Scaling up NHS swab testing for those with a medical need and, where possible, the most critical key workers ‘Pillar 2’: Mass-swab testing for critical key workers in the NHS, social care The strategy was announced and other sectors by the Secretary of State on 2nd April and has 5 key ‘Pillar 3’: Mass-antibody testing to help determine if people have immunity to coronavirus strands ‘Pillar 4’: Surveillance testing to learn more about the disease and help develop new tests and treatments ‘Pillar 5’: Spearheading a Diagnostics National Effort to build a mass-testing capacity at a completely new scale 5 Pillar 3 approach to antibody test devices • The Government is currently pursuing two main types of antibody test device: • Lab-based tests (ELISA or other immunoassay) for use within NHS and other laboratories. -

COVID-19 Evidence Bulletin 39

COVID-19 Evidence Bulletin 39 UK Guidance Public Health England PHE Literature Digest 13th Nov 2020 16th Nov 2020 18th Nov 2020 Evaluating detection of SARS-CoV-2: AntiBodies at Home study The EDSAB-HOME research study is evaluating the detection of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies using home testing kits. Updated: 18 November 2020 COVID-19: comparison of geographic allocation of cases in England by lower tier local authority Side-by-side comparison of COVID-19 cases by lower tier local authority and specimen date, based on previous and updated geographic allocation methodologies. Updated: 17 November 2020 COVID-19: geographical allocation of positive cases Statement on the geographical allocation of positive coronavirus (COVID-19) cases. Updated: 16 November 2020 Department of Health and Social Care Cohort pool testing for coronavirus (COVID-19). 16th November Information on pooled testing for universities taking part in the pooled testing pilot. Pooled testing is a safe and effective way of testing swab samples from several people at the same time. Several swab samples are combined into one plastic tube and are processed together to detect COVID-19. 16 November. New film shows importance of ventilation to reduce spread of COVID-19. Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC); 2020. New short film released by the government shows how coronavirus lingers in enclosed spaces, and how to keep your home ventilated. The film is part of the ‘Hands. Face. Space’ campaign. [Subtitled.] COVID-19: guidance on shielding and protecting people defined on medical grounds as extremely vulnerable Information for shielding and protecting people defined on medical grounds as extremely vulnerable from COVID-19.