Wiedow, John OH1918

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

35Th FIGHTER SQUADRON

35th FIGHTER SQUADRON MISSION The “Pantons” provide combat-ready F-16 C/D fighter aircraft to conduct air operations throughout the Pacific theater as tasked by United States and coalition combatant commanders. The squadron performs air and space control and force application roles including counter air, strategic attack, interdiction, and close-air support missions. It employs a full range of the latest state-of –the-art precision ordnance, day or night, all weather. Employs 32 pilots, 11 operations support personnel, 21 aircraft, and resources valued in excess of $725 million to generate and fly over 4,200 sorties per year. Flies interdiction, counter-air, close air support, and forward air controller-airborne missions. Employs night vision goggles and precision guided munitions. LINEAGE 35th Aero Squadron organized, 12 Jun 1917 Demobilized, 19 Mar 1919 Reconstituted and redesignated 35th Pursuit Squadron, 24 Mar 1923 Activated, 25 Jun 1932 Redesignated 35th Pursuit Squadron (Fighter), 6 Dec 1939 Redesignated 35th Pursuit Squadron (Interceptor), 12 Mar 1941 Redesignated 35th Fighter Squadron, 15 May 1942 Redesignated 35th Fighter Squadron, Two Engine, 19 Feb 1944 Redesignated 35th Fighter Squadron, Single Engine, 8 Jan 1946 Redesignated 35th Fighter Squadron, Jet, 1 Jan 1950 Redesignated 35th Fighter-Bomber Squadron, 20 Jan 1950 Redesignated 35th Tactical Fighter Squadron, 1 Jul 1958 Redesignated 35th Fighter Squadron, 3 Feb 1992 STATIONS Camp Kelly, TX, 12 Jun–11 Aug 1917 Etampes, France, 20 Sep 1917 Paris, France, 23 Sep 1917 Issoudun, -

Pacific Region Directory

DODEA PACIFIC DIRECTORY SY 2020 - 2021 Welcome to the 2020-21 edition of the DoDEA Pacific Directory! Inside these pages you will find helpful contact and location information, maps, and more.This document is accurate as of October 2019. We have made every effort to include the most current and accurate information. If you find an error, please know it is unintentional and we will gladly make a prompt correction to the online edition available on every PC desktop across the Pacific. Please submit all change requests to Ronald Hill @ [email protected]. or send an email request to: [email protected] Table of contents Leadership & Chain of Command .................................................................................................. 3 Advisory Councils ........................................................................................................................... 3 Office of the Director ....................................................................................................................... 4 Region Office Map ................................................................................................................ 4 Office of the Director ............................................................................................................. 5 Center for Instructional Leadership ...................................................................................... 6 Resource Management Division .......................................................................................... -

USFJ/JASDF Aeromedical Interoperability Conference

UNCLASSIFIED USFJ/JASDF Aeromedical Interoperability Conference This briefing is for information only. No U.S. government commitment to sell, Col Talib Ali loan, lease, co-develop, or co-produce HQ PACAF/SGP defense articles or services is implied or intended. Lt Col Kenji Takano Lessons Learned 374 MDG/SGP UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED Lessons Learned From Planning a Bilateral Aeromedical Conference Briefing Overview - Strategic Overview - USFJ Medical Operating Environment - Initial Planning Steps - Conference Execution - Post Event Outcome U//FOUO UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED Strategic Overview (The Big Picture) Indo-Pacific Region “We will strengthen our long-standing military relationships and encourage the development of a strong defense network with our allies and partners.” - National Security Strategy of the United States of America December 2017 “The US has enduring national interests in the Indo- Asia-Pacific...Of the five global challenges that currently drive U.S. defense planning and budgeting- ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria), North Korea, China, Russia and Iran- four are in the Indo-Asia- Pacific.” – Admiral Harry Harris, Commander USPACOM 26 April 2017 U//FOUO UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Medical Forces in Japan • SG 5AF USFJ Col Ford- USFJ/5th AF SG- Yokota AB US Marine Corps US Navy US Air Force US Army CAPT Bigby- USNH-Y CO- Yokosuka CAPT Bigby- USNH-Y CO- Yokosuka NB Col Ford- 374 MDG CC- Yokota AB COL Emerson- MEDDAC-J/ USARJ SG- Camp Zama (NAF Atsugi, MCAS Iwakuni, Sasebo NB) (NAF Atsugi, MCAS Iwakuni, Sasebo NB) -

United States-Japan Security Consultative Committee Document United States-Japan Roadmap for Realignment Implementation May 1

United States-Japan Security Consultative Committee Document United States-Japan Roadmap for Realignment Implementation May 1, 2006 by Secretary of State Rice Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld Minister of Foreign Affairs Aso Minister of State for Defense Nukaga Overview On October 29, 2005, the U.S.-Japan Security Consultative Committee (SCC) members approved recommendations for realignment of U.S. forces in Japan and related Japan Self-Defense Forces (SDF) in their document, “U.S.-Japan Alliance: Transformation and Realignment for the Future.” In that document, the SCC members directed their respective staffs “to finalize these specific and interrelated initiatives and develop plans, including concrete implementation schedules no later than March 2006.” This work has been completed and is reflected in this document. Finalization of Realignment Initiatives The individual realignment initiatives form a coherent package. When implemented, these realignments will ensure a life-of-the-alliance presence for U.S. forces in Japan. The construction and other costs for facility development in the implementation of these initiatives will be borne by the Government of Japan (GOJ) unless otherwise specified. The U.S. Government (USG) will bear the operational costs that arise from implementation of these initiatives. The two Governments will finance their realignment-associated costs consistent with their commitments in the October 29, 2005 SCC document to maintain deterrence and capabilities while reducing burdens on local communities. Key Implementation Details 1. Realignment on Okinawa (a) Futenma Replacement Facility (FRF) The United States and Japan will locate the FRF in a configuration that combines the Henoko-saki and adjacent water areas of Oura and Henoko Bays, including two runways aligned in a “V”-shape, each runway having a length of 1,600 meters plus two 100-meter overruns. -

Air Force Ground Investigation Board Report Released Jan. 25

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE GROUND ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION BOARD REPORT Hazardous Materials Storage Building 18TH LOGISTICS READINESS SQUADRON 18TH WING KADENA AIR BASE, JAPAN TYPE OF ACCIDENT: FIRE LOCATION: BUILDING 3150, KADENA AIR BASE, JAPAN DATE OF ACCIDENT: 22 JUNE 2020 BOARD PRESIDENT: COLONEL DOMINIC A. SETKA, USAF Conducted lAW Air Force Instruction 51-307 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY UNITED STATES AIR FORCE GROUND ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION Hazardous Materials Storage Building Fire Kadena Air Base, Japan 22 June 2020 On Monday, 22 June 2020, at approximately 0852 local time, a fire occurred at an 18th Logistics Readiness Squadron (LRS) hazardous materials storage building (MB), building 3150, Kadena Air Base, Japan. When the fire started, five Airmen from the 18th Civil Engineer Squadron Readiness and Emergency Management (EM) Flight, operating in two two-person teams with one team lead, were repackaging calcium hypochiorite (CH) into polycarbonate (plastic) and metal barrels for transportation to a hazardous waste disposal facility. The CH, also known as bleaching powder, has a strong oxidizing potential, which can make the chemical unstable when exposed to high heat and humidity. Approximately 90 minutes into the operation, an EM team member felt heat radiating from a pallet of CH in the southeast corner of the MB. Within minutes, the CH in the corner of the MB began to smoke and flames were observed near the southeast corner of the MB shortly after the EM team evacuated the building. Fire crews arrived on-scene within two minutes of the fire starting, coordinated with Security Forces to establish a cordon, and began to attack the fire with water. -

460 Reference

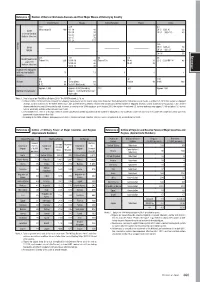

Reference 1 Number of Nuclear Warheads Arsenals and Their Major Means of Delivery by Country United States Russia United Kingdom France China 400 334 60 Minuteman III 400 SS-18 46 DF-5 CSS-4 20 ICBM ( ) SS-19 30 DF-31(CSS-10) 40 (Intercontinental ― ― SS-25 63 Ballistic Missiles) SS-27 78 RS-24 117 Missiles 148 IRBM DF-4(CSS-3) 10 ― ― ― ― MRBM DF-21(CSS-5) 122 DF-26 30 Reference 336 192 48 64 48 SLBM (Submarine Trident D-5 336 SS-N-18 48 Trident D-5 48 M-45 16 JL-2 CSS-NX-14 48 Launched ( ) SS-N-23 96 M-51 48 Ballistic Missiles) SS-N-32 48 Submarines equipped with nuclear ballistic 14 13 4 4 4 missiles 66 76 40 100 Aircraft B-2 20 Tu-95 (Bear) 60 ― Rafale 40 H-6K 100 B-52 46 Tu-160 (Blackjack) 16 Approx. 3,800 Approx. 4,350 (including 215 300 Approx. 280 Number of warheads Approx. 1,830 tactical nuclear warheads) Notes: 1. Data is based on “The Military Balance 2019,” the SIPRI Yearbook 2018, etc. 2. In March 2019, the United States released the following figures based on the new Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty between the United States and Russia as of March 1, 2019: the number of deployed strategic nuclear warheads for the United States was 1,365 and the delivery vehicles involved 656 missiles/aircraft; the number of deployed strategic nuclear warheads for Russia was 1,461 and the delivery vehicles involved 524 missiles/aircraft. However, according to the SIPRI database, as of January 2018, the number of deployed U.S. -

Reports and Maps of the Military Geology Unit

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Open-File Report 97-175 Reports and Maps of the Military Geology Unit 1942-1975 compiled by Selma Bonham 1981 edited by William Leith 1997 Reston, Virginia 1997 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ....................................................... i i i WASHINGTON OFFICE. Series reports for office of the Chief of Engineers, 1942-1963, and Defense Intelligence Agency, 1963-1965 ................ 1 Strategic Engineering Studies, 1942 1945 .......................... 4 Engineering Notes, 1944 1953 .................................. 1 2 Joint Army-Navy Intelligence Studies, 1946-1948 ................. 13 Basic Map Compilations, 1949-1965 ............................. 14 Engineer Intelligence Studies, 1952-1964 ........................ 18 Engineer Intelligence Guides, 1957-1964 ...................... ... 21 Engineer Intelligence Notes, 1959 ................................ 21 Basic Terrain Studies, Alaska, 1960-1965 ........................ 22 Pacific Engineer Intelligence Program, 1960-1965 ................. 24 Special reports for: Office of the Chief of Engineers, 1942-1963 ....................... 25 Air Force Cambridge Research Laboratories, 1957-1970 ............. 39 Advanced Research Projects Agency, 1962-1973 ................... 42 Defense Intelligence Agency, 1963-1971 .......................... 45 Other agencies, 1942-1972 .................................... 4 6 HAWAII OFFICE Engineering and Terrain Intelligence Team Reports for Armed Forces Mid- Pacific, 1 944-1 945 ......................................... -

US Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) Activities in Japan 1945 – 2015: a Visual Guide

Volume 14 | Issue 6 | Number 6 | Article ID 4868 | Mar 15, 2016 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus US Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) Activities in Japan 1945 – 2015: A Visual Guide Desmond Ball, Richard Tanter Introduction precise role in the event of combat. But all of this means that for those concerned to assess 'Due to government secrecy, our citizens are the consequences of US bases in foreign often ignorant of the fact that our garrisons countries need to attend to signals intelligence encircle the planet. This vast network of bases whose constant and efficient functioning American bases on every continent except is a necessary prerequisite for power Antarctica actually constitutes a new form of projection. empire -- an empire of bases.' 'Signals intelligence' or SIGINT is then one of Chalmers Johnson, America's Empire of Bases the highest priorities for any military, and critical to US global operations. Signals Nobody, probably not even the Pentagon, intelligence bases range from huge Circularly- knows exactly how many military bases the disposed Antenna Arrays or 'elephant cages' United States maintains in foreign countries, or more than 400 metres in diameter picking up how many have come and gone in the past. military transmissions from more than 7,000 Today, there are certainlymore than a kms away, to farms of parabolic antennas thousand, and still increasing, and expanding downlinking transmissions collected from the into new fronts, especially in Central Africa. A ground by SIGINT satellites in geosynchronous 'base' can mean many different things, but the orbit, through to small antennas in embassies ones that usually receive most attention are and consulates picking up local cell phone those where the mechanics of American power transmissions between towers. -

KODY LOTNISK ICAO Niniejsze Zestawienie Zawiera 8372 Kody Lotnisk

KODY LOTNISK ICAO Niniejsze zestawienie zawiera 8372 kody lotnisk. Zestawienie uszeregowano: Kod ICAO = Nazwa portu lotniczego = Lokalizacja portu lotniczego AGAF=Afutara Airport=Afutara AGAR=Ulawa Airport=Arona, Ulawa Island AGAT=Uru Harbour=Atoifi, Malaita AGBA=Barakoma Airport=Barakoma AGBT=Batuna Airport=Batuna AGEV=Geva Airport=Geva AGGA=Auki Airport=Auki AGGB=Bellona/Anua Airport=Bellona/Anua AGGC=Choiseul Bay Airport=Choiseul Bay, Taro Island AGGD=Mbambanakira Airport=Mbambanakira AGGE=Balalae Airport=Shortland Island AGGF=Fera/Maringe Airport=Fera Island, Santa Isabel Island AGGG=Honiara FIR=Honiara, Guadalcanal AGGH=Honiara International Airport=Honiara, Guadalcanal AGGI=Babanakira Airport=Babanakira AGGJ=Avu Avu Airport=Avu Avu AGGK=Kirakira Airport=Kirakira AGGL=Santa Cruz/Graciosa Bay/Luova Airport=Santa Cruz/Graciosa Bay/Luova, Santa Cruz Island AGGM=Munda Airport=Munda, New Georgia Island AGGN=Nusatupe Airport=Gizo Island AGGO=Mono Airport=Mono Island AGGP=Marau Sound Airport=Marau Sound AGGQ=Ontong Java Airport=Ontong Java AGGR=Rennell/Tingoa Airport=Rennell/Tingoa, Rennell Island AGGS=Seghe Airport=Seghe AGGT=Santa Anna Airport=Santa Anna AGGU=Marau Airport=Marau AGGV=Suavanao Airport=Suavanao AGGY=Yandina Airport=Yandina AGIN=Isuna Heliport=Isuna AGKG=Kaghau Airport=Kaghau AGKU=Kukudu Airport=Kukudu AGOK=Gatokae Aerodrome=Gatokae AGRC=Ringi Cove Airport=Ringi Cove AGRM=Ramata Airport=Ramata ANYN=Nauru International Airport=Yaren (ICAO code formerly ANAU) AYBK=Buka Airport=Buka AYCH=Chimbu Airport=Kundiawa AYDU=Daru Airport=Daru -

CAT and Air America in Japan by Dr

CAT and Air America in Japan by Dr. Joe F. Leeker First published on 4 March 2013, last updated on 24 August 2015 I) A new beginning: As has been shown elsewhere, Civil Air Transport, after its glorious days during the civil war in mainland China, had to go into exile on the Island of Formosa in late 1949. With only very few places left where to fly, CAT had enormous financial problems at the end of December 1949, although on 1 November 1949, CAT and the CIA had signed an agreement by which the CIA promised to subsidize CAT by an amount of up to $ 500,000.1 In order to prevent the fleets of China National Aviation Corp. (CNAC) and Central Air Transport Corp. (CATC) detained at Hong Kong’s Kai Tak airport from falling into the hands of Communist China, General Chennault and Whiting Willauer, the main owners of CAT, had bought both fleets from the Nationalist Government of China against personal promissory notes for $ 4.75 million – an amount of money they did not have2 – and registered all aircraft in the United States to Civil Air Transport, Inc. (CATI), Dover, DE on 19 December 1949. But it was not until late 1952 that the former CATC and CNAC aircraft were awarded to CAT by court decision,3 and so this long lasting lawsuit, too, meant enormous financial expenses to CAT. Finally, in order to prevent their own fleet from falling into the hands of Communist China, on 5 January 1950, the Chennault / Willauer partnership transferred their aircraft to C.A.T. -

Measures for U.S. Military Base Promotion of Civil-Military Dual-Use of Yokota Air Base Handling Issues Associated with U.S

Measures for U.S. Military Base Promotion of Civil-Military Dual-Use of Yokota Air Base Handling Issues Associated with U.S. Military Bases “Civil-military dual-use of Yokota Air Base,” which would enable the use of the base for commercial flights, will supplement airport functions in the National Capital Region and There are eight U.S. military bases in Tokyo, and their impact on the daily lives of Tokyo improve air access in the western part of the region. residents ranges from aircraft noise to concern about incidents and accidents. To ensure the Following agreement between Japan and the United States to study the feasibility of safety of Tokyo residents and to promote community development, the TMG, in cooperation civil-military dual-use of Yokota Air Base at the 2003 Japan-U.S. Summit, the TMG has been with relevant local governments, is urging the central government and the U.S. Armed Forces working closely with the central government for early realization of dual-use of the base. to work toward the consolidation, downscaling, and reversion of U.S. military bases in Tokyo, as well as to resolve various problems caused by these bases. The TMG also works with the U.S. Armed Forces to cooperate in times of disasters and other emergencies. ■ Significance of Civil-Military Dual-Use of Yokota Air Base • Supplementing Airport Functions in the National Capital Region ■ Although airport capacity in the National Capital Region is increasing in stages through the re-expansion U.S. Military Bases in Tokyo of Haneda Airport and runway extension at Narita Airport, it is projected that capacity will reach its limit In Tokyo, there are eight U.S. -

Realignment of U.S. Forces in Japan (PDF)

Realignment of U.S. forces in Japan (Okinawa) -Relocation of U.S. forces’ aviation training exercises in Japan has been conducted since 2006 (Chitose, Misawa, Hyakuri, Komatsu, (Mainland Japan) Relocation of Marine Corps Tsuiki, Nyutabaru). Air Station Futenma -Agreement on aviation training relocation to Guam and other Replacement facility will be established in Camp locations in 2011 (Training relocation was implemented 93 times Schwab-Henokosaki area and adjacent waters. KC-130 as of the end of December 2018 (incl relocation to Guam and was relocated to Iwakuni (completed in August 2014). other locations)). -Training relocation of MV-22 Ospreys, etc. at Marine Corps Air Station Futenma outside of Okinawa was implemented from FY 2016 (once in Guam, and five times in Japan through the end of December 2017) ●Chitose Camp Schwab Relocation of US Marine Corps personnel to locations outside Japan Yokota Air Base -Relocation of Japan Air Self- -Approx. 9000 (at capacity) U.S. Marine Corps and their associated Defense Force(JASDF) Air dependents from Okinawa to locations outside of Japan Misawa Air Base Defense Command HQ from Kadena Airbase *End-State for the U.S. Marine Corps forces in Okinawa will be consistent Fuchu (March 2012) Army Tank FarmNo.1 with the levels envisioned in the Roadmap. Camp Kuwae -Five CV-22 Ospreys Deployed Camp Zukeran *The number of U.S. marines in Guam is to be approxmately 5, 000 (at (October 2018) Makiminato Service Area MCAS Futenma capacity). -Facility and infrastructure development costs for relocation to Guam Hyakuri Camp Zama Naha Port Facility ● Naha Overall cost: 8.6 billion US dollars (provisional estimate by the U.S.