Blackbeard's Surname Richard Coates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson Adapted by Bryony Lavery

TREASURE ISLAND BY ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON ADAPTED BY BRYONY LAVERY DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. TREASURE ISLAND Copyright © 2016, Bryony Lavery All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of TREASURE ISLAND is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan- American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for TREASURE ISLAND are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No professional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., and paying the requisite fee. Inquiries concerning all other rights should be addressed to United Agents, 12-26 Lexington Street, London, England, W1F 0LE. -

Motion Picture Posters, 1924-1996 (Bulk 1952-1996)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt187034n6 No online items Finding Aid for the Collection of Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Processed Arts Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Elizabeth Graney and Julie Graham. UCLA Library Special Collections Performing Arts Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Collection of 200 1 Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Descriptive Summary Title: Motion picture posters, Date (inclusive): 1924-1996 Date (bulk): (bulk 1952-1996) Collection number: 200 Extent: 58 map folders Abstract: Motion picture posters have been used to publicize movies almost since the beginning of the film industry. The collection consists of primarily American film posters for films produced by various studios including Columbia Pictures, 20th Century Fox, MGM, Paramount, Universal, United Artists, and Warner Brothers, among others. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections. -

Ye Intruders Beware: Fantastical Pirates in the Golden Age of Illustration

YE INTRUDERS BEWARE: FANTASTICAL PIRATES IN THE GOLDEN AGE OF ILLUSTRATION Anne M. Loechle Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of the History of Art Indiana University November 2010 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee _________________________________ Chairperson, Sarah Burns, Ph.D. __________________________________ Janet Kennedy, Ph.D. __________________________________ Patrick McNaughton, Ph.D. __________________________________ Beverly Stoeltje, Ph.D. November 9, 2010 ii ©2010 Anne M. Loechle ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii Acknowledgments I am indebted to many people for the help and encouragement they have given me during the long duration of this project. From academic and financial to editorial and emotional, I was never lacking in support. I am truly thankful, not to mention lucky. Sarah Burns, my advisor and mentor, supported my ideas, cheered my successes, and patiently edited and helped me to revise my failures. I also owe her thanks for encouraging me to pursue an unorthodox topic. From the moment pirates came up during one of our meetings in the spring of 2005, I was hooked. She knew it, and she continuously suggested ways to expand the idea first into an independent study, and then into this dissertation. My dissertation committee – Janet Kennedy, Patrick McNaughton, and Beverly Stoeltje – likewise deserves my thanks for their mentoring and enthusiasm. Other scholars have graciously shared with me their knowledge and input along the way. David M. Lubin read a version of my third chapter and gave me helpful advice, opening up to me new ways of thinking about Howard Pyle in particular. -

Treasure Island Exploring the Play at Home

Treasure Island Exploring the Play at Home If you’re watching Treasure Island at home and would like to find out more out the production, there are a number of different resources that you can explore and activities you might like to try. About the Production Treasure Island was first performed at the National Theatre in 2014. The production was directed by Polly Findlay. Based on the 1883 novel by Robert Louis Stevenson, this stage production was adapted by Bryony Lavery. You can find full details of the cast and production team below: Cast Jim Hawkins: Patsy Ferran Grandma: Gillian Hanna Bill Bones: Aidan Kelly Dr Livesey: Alexandra Maher Squire Trelawny/Voice of the Parrot: Nick Fletcher Mrs Crossley: Alexandra Maher Red Ruth: Heather Dutton Job Anderson: Raj Bajaj Silent Sue: Lena Kaur Black Dog: Daniel Coonan Blind Pew: David Sterne Captain Smollett: Paul Dodds Long John Silver: Arthur Darvill Lucky Mickey: Jonathan Livingstone Joan the Goat: Claire-Louise Cordwell Israel Hands: Angela de Castro Dick the Dandy: David Langham Killigrew the Kind: Alastair Parker George Badger: Oliver Birch Grey: Tim Samuels Ben Gunn: Joshua James Shanty Singer: Roger Wilson Parrot (Captain Flint): Ben Thompson Production team Director: Polly Findlay Adaptation: Bryony Lavery Designer: Lizzie Clachan Lighting Designer: Bruno Poet Composer: John Tams Fight Director: Bret Yount Movement Director: Jack Murphy Music and Sound Designer: Dan Jones Illusions: Chris Fisher Comedy Consultant: Clive Mendus Creative Associate: Carolina Valdés You might like to use the internet to research some of these artists to find out more about their careers. If you would like to find out about careers in the theatre, there’s lots of useful information on the Discover Creative Careers website. -

The Newgate Calendar Supplement 3 Edited by Donal Ó Danachair

The Newgate Calendar Supplement 3 Edited By Donal Ó Danachair Published by the Ex-classics Project, year http://www.exclassics.com Public Domain The Newgate Calendar CONTENTS SIR HENRY MORGAN. Pirate who became Governor of Jamaica (1688) ................ 4 MAJOR STEDE BONNET. Wealthy Landowner turned Pirate, Hanged 10th December 1718 ............................................................................................................ 13 ANN HOLLAND Wife of a highwayman with whom she robbed many people. Executed 1705 .............................................................................................................. 15 DICK MORRIS. Cunning and audacious swindler, executed 1706 ........................... 16 WILLIAM NEVISON Highwayman who robbed his fellows. Executed at York, 4th May 1684 ..................................................................................................................... 19 CAPTAIN AVERY Pirate who died penniless, having been robbed of his booty by merchants ..................................................................................................................... 24 CAPTAIN MARTEL Pirate ........................................................................................ 31 CAPTAIN TEACH alias BLACK BEARD, the Most Famous Pirate of all. ............... 33 CAPTAIN EDWARD ENGLAND Pirate .................................................................. 39 CAPTAIN CHARLES VANE. Pirate ......................................................................... 49 CAPTAIN JOHN RACKAM. -

TREASURE ISLAND the NOVEL and the MUSICAL 2 STUDY MATERIALS

Maine State Music Theatre Curtis Memorial Library, Topsham Public Library, and Patten Free Library present A STUDY GUIDE TO TREASURE ISLAND The NOVEL and the MUSICAL 2 STUDY MATERIALS TREASURE ISLAND: THE NOVEL Robert Louis Stevenson Page 3 Treasure Island in Literary History Page 5 Fun Facts About the Novel Page 6 Historical Context of the Novel Page 7 Adaptations of Treasure Island on Film and Stage Page 9 Treasure Island: Themes Page 10 Treasure Island: Synopsis of the Novel Page 11 Treasure Island: Characters in the Novel Page 13 Treasure Island: Glossary Page 15 TREASURE ISLAND A Musical Adventure: THE ROBIN & CLARK MUSICAL Artistic Statement Page 18 The Creators of the Musical Page 19 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Themes Page 20 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Synopsis & Songs Page 21 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Cast of Characters Page 24 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: World Premiere Page 26 Press Quotes Page 27 QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION Page 28 MSMT’s Treasure Island A Musical Adventure Page 29 3 TREASURE ISLAND: THE NOVEL ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, on November 13, 1850, to Thomas and Margaret Stevenson. Lighthouse design was his father's and his family's profession, so at age seventeen, he enrolled at Edinburgh University to study engineering, with the goal of following in the family business. Lighthouse design never appealed to Stevenson, though, and he began studying law instead. His spirit of adventure truly began to appear at this stage, and during his summer vacations he traveled to France to be around young writers and painters. -

Unit 8 Teacher Guide Grade 4 Treasure Island Grade 4 Unit 8

¬CKLA FLORIDA Unit 8 Teacher Guide Grade 4 Treasure Island Grade 4 Unit 8 Treasure Island Teacher Guide ISBN 978-1-68391-662-8 © 2015 The Core Knowledge Foundation and its licensors www.coreknowledge.org Revised and additional material © 2021 Amplify Education, Inc. and its licensors www.amplify.com All Rights Reserved. Core Knowledge Language Arts and CKLA are trademarks of the Core Knowledge Foundation. Trademarks and trade names are shown in this book strictly for illustrative and educational purposes and are the property of their respective owners. References herein should not be regarded as affecting the validity of said trademarks and trade names. Printed in the USA 01 BR 2020 G4_U07_TG_FL_20200909.indb 2 9/15/20 10:55 AM Grade 4 | Unit 8 Contents TREASURE ISLAND Introduction 1 Lesson 1 The Old Seadog 8 Core Connections (45 min.) Reading (45 min.) • Review Geography and History • Introduce the Reader • Introduce Pirates and Piracy • Introduce the Chapter • Introduce Nautical Terms • Read Chapter 1 • Chapter Discussion • Word Work: Driving Lesson 2 The Sea Chest 34 Reading (45 min.) Language (30 min.) Writing (15 min.) • Introduce the Chapter • Grammar: Modal Auxiliary Verbs • Introduce an Adventure • Read Chapter 2 • Morphology: Introduce Root bio Story • Chapter Discussion • Word Work: Ransack Lesson 3 Characters in Adventure Stories 64 Reading (45 min.) Writing (45 min.) • Review the Chapter • Choose a Setting • Read Chapter 2 • Plan a Character Sketch • Chapter Discussion • Word Work: Stun Lesson 4 A Real Adventure 74 Reading -

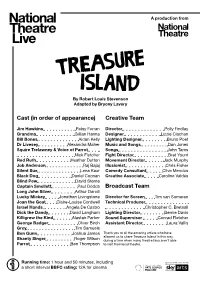

Cast (In Order of Appearance) Creative Team

A production from By Robert Louis Stevenson Adapted by Bryony Lavery Cast (in order of appearance) Creative Team Jim Hawkins Patsy Ferran Director Polly Findlay Grandma Gillian Hanna Designer Lizzie Clachan Bill Bones Aidan Kelly Lighting Designer Bruno Poet Dr Livesey Alexandra Maher Music and Songs Dan Jones Squire Trelawney & Voice of Parrot Songs John Tams Nick Fletcher Fight Director Bret Yount Red Ruth Heather Dutton Movement Director Jack Murphy Job Anderson Raj Bajaj Illusionist Chris Fisher Silent Sue Lena Kaur Comedy Consultant Clive Mendus Black Dog Daniel Coonan Creative Associate Caroline Valdés Blind Pew David Sterne Captain Smollett Paul Dodds Broadcast Team Long John Silver Arthur Darvill Lucky Mickey Jonathan Livingstone Director for Screen Tim van Someren Joan the Goat Claire-Louise Cordwell Technical Producer Israel Hands Angela De Castro Christopher C. Bretnall Dick the Dandy David Langham Lighting Director Bernie Davis Killigrew the Kind Alastair Parker Sound Supervisor Conrad Fletcher George Badger Oliver Birch Assistant Director Laura Vallis Grey Tim Samuels Ben Gunn Joshua James Thank you to all the amazing artists who have allowed us to share Treasure Island in this way, Shanty Singer Roger Wilson during a time when many theatre fans aren’t able Parrot Ben Thompson to visit their local theatre. Running time: 1 hour and 50 minutes, including a short interval BBFC rating: 12A for cinema Help Jim Hawkins find the buried gold! Can you trace your way from the ship to X marks the spot and the treasure? Image: Freepik.com Image: Did you know? Excerpts from Treasure Island show programme articles by Andrew Lambert, David Cordingly and Tristan Gooley. -

September 19 – International Talk Like a Pirate Day – Drill

September 19 – International Talk Like a Pirate Day – Drill “This is a Drill” Type of Event: Civil Disturbance: Invasion of pirates ---Blackbeard (and his crew – Black Ceaser, Israel Hands, Lieutenant Richards), Zheng Yi Sao, Jean Lafitte, Micajah and Wiley Harpe Pirates Duration of exercise: Wednesday, Sept 19 from 0000 to2400 (12:00am to 11:59pm) You may participate any time after that if you wish Place of occurrence: The Southeast Texas Region Objective: The goal of a drill is to request resources through WebEOC following your processes to fight against the Pirates and push them back into the sea so they never return. Participants: Sentinels and their users District Coordinators TDEM Critical Information Systems (CIS) SOC Methodology: WebEOC Event and STAR board Active Incident Name: Exercise 09/19/2018 International Talk Like Pirate Drill Exercise Directors: Black Dollie Winn (Janette Walker) , 832-690-8765 Thiefin’ Jackie Sneed (Jennifer Suter) Emergency Scenario: The above pirate have risen from their grave and traveled to the Gulf Coast during Tuesday night (9/18) and have already invaded the coastal counties (Matagorda, Brazoria, Galveston, and Chambers) and are working their way to the most northern counties (Walker, Colorado, Austin, Sabine). Each county they invade, they commandeer the liquor and supply chain stores as well as EOCs. Inject: AVAST Ye!! Ye land lovers, we gentleman o' fortunes be havin' risen from Davy Jones` Locker an' be are invadin' yer area an' plan t' commandeer all yer resources an' government land. We be tired o' th' water an' be movin' inland. We be havin' already invaded th' coastal counties an' movin' up t' th' northern counties. -

Archaeology of Piracy Between Caribbean Sea and the North American Coast of 17Th and 18Th Centuries: Shipwrecks, Material Culture and Terrestrial Perspectives

Journal of Caribbean Archaeology Copyright 2019 ISBN 1524-4776 ARCHAEOLOGY OF PIRACY BETWEEN CARIBBEAN SEA AND THE NORTH AMERICAN COAST OF 17TH AND 18TH CENTURIES: SHIPWRECKS, MATERIAL CULTURE AND TERRESTRIAL PERSPECTIVES Jean Soulat Laboratoire LandArc – Centre Michel de Boüard, Craham UMR 6273 Groupe de Recherche en Archéométrie, Université Laval, Québec 29, rue de Courbuisson 77920 Samois-sur-Seine – France [email protected] John de Bry Center for Historical Archaeology 140 Warsteiner Way, Suite 204 Melbourne Beach, Florida 32951 – USA [email protected] The archaeology of piracy in the 17th and 18th centuries remains a poorly developed discipline in the world. American universities in connection with local authorities were the first to fund and support such research programs on the east coast of the United States and the Caribbean. The study of the shipwreck of the pirate Edward Teach (Blackbeard), the Queen Anne's Revenge 1718, is a very good example of this success. However, a work of crossing archaeological data deserves to be carried out for all the sites brought to light, in particular in the Caribbean area, on the North American coast, without forgetting the Indian Ocean. The synthetic work of Charles R. Ewen and Russell K. Skowronek published in 2006 and 2016 by the University of Florida is an important first step. They treat shipwrecks as well as land occupations, and go back for a long time on the percceived ideas related to the true image of Pirates. However, there is a lack of material culture studies from these sites probably related to the lack of scientific publications of these objects. -

PERRY/REECE CASTING Penny Perry 310-422-1581-Cell Phone 818-905-9917-Home Phone

PERRY/REECE CASTING Penny Perry 310-422-1581-Cell Phone 818-905-9917-Home Phone MOTION PICTURES PORKY’S: THE COLLEGE YEARS Larry Levinson Productions Adam Wylie Producer: Larry Levinson Vic Polizos Director: Brian Trenchard-Smith THE INVITED Dark Portal, LLC. Lou Diamond Phillips Producer: Dan Kaplow Megan Ward Director: Ryan McKinney Brenda Vaccaro Pam Greer WHEN CALLS THE HEART Maggie Grace Producer & Director: Michael Landon Peter Coyote DISAPPEARANCES Border Run Productions Kris Kristofferson Producer & Director: Jay Craven Genevieve Bujold Lothaire Bluteau Luis Guzman FEAR X John Turturro Producer: Henrik Danstrup James Remar Director: Nicolas Winding Refn Deborah Unger DIAL 9 FOR LOVE Pleswin Entertainment Jeanne Tripplehorn Producer: Eric Pleskow /Leon de Winter Liev Schreiber Director: Kees Van Oostrom Louise Fletcher Co-Producer: Penny Perry THE HOLLYWOOD SIGN Pleswin Entertainment Burt Reynolds Producer: Eric Pleskow/Leon de Winter Rod Steiger Producer: Penny Perry Tom Berenger Director: Sonke Wortmann EXTREME OPS Diamant/Cohen Productions Brigette Wilson-Sampras Director: Christian Dugay Devon Sawa Rupert Graves FEAR.COM Diamant/Cohen Productions Stephen Dorff Producer: Moshe Diamant Natascha McElhone Director: William Malone Stephen Rea BIG BAD LOVE Sun, Moon & Stars Prod. Deborah Winger Producer: Barry Navidi Arliss Howard Director: Arliss Howard Rosanna Arquette Paul LeMat THE MUSKETEER Universal Mena Suvari Director: Peter Hyams Tim Roth Producer: Moshe Diamant Catherine Denueve Producer: Mark Damon Stephen Rea Nick Moran -

Movie Time Descriptive Video Service

DO NOT DISCARD THIS CATALOG. All titles may not be available at this time. Check the Illinois catalog under the subject “Descriptive Videos or DVD” for an updated list. This catalog is available in large print, e-mail and braille. If you need a different format, please let us know. Illinois State Library Talking Book & Braille Service 300 S. Second Street Springfield, IL 62701 217-782-9260 or 800-665-5576, ext. 1 (in Illinois) Illinois Talking Book Outreach Center 125 Tower Drive Burr Ridge, IL 60527 800-426-0709 A service of the Illinois State Library Talking Book & Braille Service and Illinois Talking Book Centers Jesse White • Secretary of State and State Librarian DESCRIPTIVE VIDEO SERVICE Borrow blockbuster movies from the Illinois Talking Book Centers! These movies are especially for the enjoyment of people who are blind or visually impaired. The movies carefully describe the visual elements of a movie — action, characters, locations, costumes and sets — without interfering with the movie’s dialogue or sound effects, so you can follow all the action! To enjoy these movies and hear the descriptions, all you need is a regular VCR or DVD player and a television! Listings beginning with the letters DV play on a VHS videocassette recorder (VCR). Listings beginning with the letters DVD play on a DVD Player. Mail in the order form in the back of this catalog or call your local Talking Book Center to request movies today. Guidelines 1. To borrow a video you must be a registered Talking Book patron. 2. You may borrow one or two videos at a time and put others on your request list.