Treasure Island 51 Christy Di Frances

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Broons': Scotland's Happy Family

Jackie Kay's Representation of 'The Broons': Scotland's Happy Family Author(s): Mª del Coral Calvo Maturana Source: eSharp , Special Issue: Spinning Scotland: Exploring Literary and Cultural Perspectives (2009), pp. 109-143 URL: http://www.gla.ac.uk/esharp ISSN: 1742-4542 Copyright in this work remains with the author. _______________________________________________________ eSharp is an international online journal for postgraduate research in the arts, humanities, social sciences and education. Based at the University of Glasgow and run by graduate students, it aims to provide a critical but supportive entry to academic publishing for emerging academics, including postgraduates and recent postdoctoral students. [email protected] eSharp Special Issue: Spinning Scotland Jackie Kay’s Representation of ‘The Broons’: Scotland’s Happy Family Mª del Coral Calvo Maturana (Universidad de Granada) 1. Introduction This paper focuses on the contemporary Scottish poet Jackie Kay and the comic strip ‘The Broons’ by studying Jackie Kay’s representation of this family in contrast to its characterisation in the comic strip. 1 This study presents a brief introduction to Jackie Kay and ‘The Broons’ and pays attention to Kay’s referential portrayal of this Scottish family in five of her poems: ‘Maw Broon Visits a Therapist’ (2006a, p.46-47), ‘Paw Broon on the Starr Report’ (2006a, p.57), ‘The Broon’s Bairn’s Black’ (2006a, p.61), ‘There’s Trouble for Maw Broon’ (2005, p.13-14) and ‘Maw Broon goes for colonic irrigation’ (unpublished). 2 Each of the poems will be approached stylistically by using the advantages offered by corpus linguistics methodology; in particular, the program Wordsmith Tools 3.0. -

Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson Adapted by Bryony Lavery

TREASURE ISLAND BY ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON ADAPTED BY BRYONY LAVERY DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. TREASURE ISLAND Copyright © 2016, Bryony Lavery All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of TREASURE ISLAND is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan- American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for TREASURE ISLAND are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No professional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., and paying the requisite fee. Inquiries concerning all other rights should be addressed to United Agents, 12-26 Lexington Street, London, England, W1F 0LE. -

Fudge the Elf

1 Fudge The Elf Ken Reid The Laura Maguire collection Published October 2019 All Rights Reserved Sometime in the late nineteen nineties, my daughter Laura, started collecting Fudge books, the creation of the highly individual Ken Reid. The books, the daily strip in 'The Manchester Evening News, had been a part of my childhood. Laura and her brother Adam avidly read the few dog eared volumes I had managed to retain over the years. In 2004 I created a 'Fudge The Elf' website. This brought in many contacts, collectors, individuals trying to find copies of the books, Ken's Son, the illustrator and colourist John Ridgeway, et al. For various reasons I have decided to take the existing website off-line. The PDF faithfully reflects the entire contents of the original website. Should you wish to get in touch with me: [email protected] Best Regards, Peter Maguire, Brussels 2019 2 CONTENTS 4. Ken Reid (1919–1987) 5. Why This Website - Introduction 2004 6. Adventures of Fudge 8. Frolics With Fudge 10. Fudge's Trip To The Moon 12. Fudge And The Dragon 14. Fudge In Bubbleville 16. Fudge In Toffee Town 18. Fudge Turns Detective Savoy Books Editions 20. Fudge And The Dragon 22. Fudge In Bubbleville The Brockhampton Press Ltd 24. The Adventures Of Dilly Duckling Collectors 25. Arthur Gilbert 35. Peter Hansen 36. Anne Wilikinson 37. Les Speakman Colourist And Illustrator 38. John Ridgeway Appendix 39. Ken Reid-The Comic Genius 3 Ken Reid (1919–1987) Ken Reid enjoyed a career as a children's illustrator for more than forty years. -

Dundee and Perth

A REPUTATION FOR EXCELLENCE Volume 3: Dundee and Perth Introduction A History of the Dundee and Perth Printing Industries, is the third booklet in the series A Reputation for Excellence; others are A History of the Edinburgh Printing Industry (1990) and A History of the Glasgow Printing Industry (1994). The first of these gives a brief account of the advent of printing to Scotland: on September 1507 a patent was granted by King James IV to Walter Chepman and Andro Myllar ‘burgessis of our town of Edinburgh’. At His Majesty’s request they were authorised ‘for our plesour, the honour and profitt of our realme and liegis to furnish the necessary materials and capable workmen to print the books of the laws and other books necessary which might be required’. The partnership set up business in the Southgait (Cowgate) of Edinburgh. From that time until the end of the seventeenth century royal patents were issued to the trade, thus confining printing to a select number. Although there is some uncertainty in establishing precisely when printing began in Dundee, there is evidence that the likely date was around 1547. In that year John Scot set up the first press in the town, after which little appears to have been done over the next two centuries to develop and expand the new craft. From the middle of the eighteenth century, however, new businesses were set up and until the second half of the present century Dundee was one of Scotland's leading printing centres. Printing in Perth began in 1715, with the arrival there of one Robert Freebairn, referred to in the Edinburgh booklet. -

Ye Intruders Beware: Fantastical Pirates in the Golden Age of Illustration

YE INTRUDERS BEWARE: FANTASTICAL PIRATES IN THE GOLDEN AGE OF ILLUSTRATION Anne M. Loechle Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of the History of Art Indiana University November 2010 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee _________________________________ Chairperson, Sarah Burns, Ph.D. __________________________________ Janet Kennedy, Ph.D. __________________________________ Patrick McNaughton, Ph.D. __________________________________ Beverly Stoeltje, Ph.D. November 9, 2010 ii ©2010 Anne M. Loechle ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii Acknowledgments I am indebted to many people for the help and encouragement they have given me during the long duration of this project. From academic and financial to editorial and emotional, I was never lacking in support. I am truly thankful, not to mention lucky. Sarah Burns, my advisor and mentor, supported my ideas, cheered my successes, and patiently edited and helped me to revise my failures. I also owe her thanks for encouraging me to pursue an unorthodox topic. From the moment pirates came up during one of our meetings in the spring of 2005, I was hooked. She knew it, and she continuously suggested ways to expand the idea first into an independent study, and then into this dissertation. My dissertation committee – Janet Kennedy, Patrick McNaughton, and Beverly Stoeltje – likewise deserves my thanks for their mentoring and enthusiasm. Other scholars have graciously shared with me their knowledge and input along the way. David M. Lubin read a version of my third chapter and gave me helpful advice, opening up to me new ways of thinking about Howard Pyle in particular. -

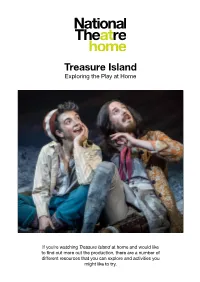

Treasure Island Exploring the Play at Home

Treasure Island Exploring the Play at Home If you’re watching Treasure Island at home and would like to find out more out the production, there are a number of different resources that you can explore and activities you might like to try. About the Production Treasure Island was first performed at the National Theatre in 2014. The production was directed by Polly Findlay. Based on the 1883 novel by Robert Louis Stevenson, this stage production was adapted by Bryony Lavery. You can find full details of the cast and production team below: Cast Jim Hawkins: Patsy Ferran Grandma: Gillian Hanna Bill Bones: Aidan Kelly Dr Livesey: Alexandra Maher Squire Trelawny/Voice of the Parrot: Nick Fletcher Mrs Crossley: Alexandra Maher Red Ruth: Heather Dutton Job Anderson: Raj Bajaj Silent Sue: Lena Kaur Black Dog: Daniel Coonan Blind Pew: David Sterne Captain Smollett: Paul Dodds Long John Silver: Arthur Darvill Lucky Mickey: Jonathan Livingstone Joan the Goat: Claire-Louise Cordwell Israel Hands: Angela de Castro Dick the Dandy: David Langham Killigrew the Kind: Alastair Parker George Badger: Oliver Birch Grey: Tim Samuels Ben Gunn: Joshua James Shanty Singer: Roger Wilson Parrot (Captain Flint): Ben Thompson Production team Director: Polly Findlay Adaptation: Bryony Lavery Designer: Lizzie Clachan Lighting Designer: Bruno Poet Composer: John Tams Fight Director: Bret Yount Movement Director: Jack Murphy Music and Sound Designer: Dan Jones Illusions: Chris Fisher Comedy Consultant: Clive Mendus Creative Associate: Carolina Valdés You might like to use the internet to research some of these artists to find out more about their careers. If you would like to find out about careers in the theatre, there’s lots of useful information on the Discover Creative Careers website. -

Introduction Herbert Allingham: a Common Writer Born 1867 This Is A

Introduction Herbert Allingham: A Common Writer Born 1867 This is a study of the working life of Herbert Allingham: a life that may formally be held to have commenced with the publication of his first serial story in 1886. It is, however, a central argument that the significance of Allingham’s career only becomes apparent when it is viewed in wider social, economic and cultural contexts. These include the characteristic patterns of capitalistic development as well as specific historical factors contributing to the proliferation of cheap, nationally distributed periodicals designed for working class family entertainment at a time when the working classes comprised the majority of the population. Allingham was born into a family that was still functioning as a business entity. During his lifetime this became a very much less common situation (in towns at least) but, as the family’s potential as a unit of production declined, its importance as an agent of consumption increased. Broadly, people’s domestic expectations rose. Though this was a material process, it possessed an underlying moral impetus that may have been a legacy of the teachings of nineteenth century evangelical Christians and social reformers. In this thesis the word family works hard. As well as referring to people in their domestic, gendered or generational relationships to one another, it is also used collectively for people, businesses, or artefacts (such as magazines) that were linked by their common interests. Flavouring all these is an evaluative usage of ‘family’ to convey a generalised approbation, a benison of social respectability. In cultural terms family entertainment is marketed as something to be shared. -

The Newgate Calendar Supplement 3 Edited by Donal Ó Danachair

The Newgate Calendar Supplement 3 Edited By Donal Ó Danachair Published by the Ex-classics Project, year http://www.exclassics.com Public Domain The Newgate Calendar CONTENTS SIR HENRY MORGAN. Pirate who became Governor of Jamaica (1688) ................ 4 MAJOR STEDE BONNET. Wealthy Landowner turned Pirate, Hanged 10th December 1718 ............................................................................................................ 13 ANN HOLLAND Wife of a highwayman with whom she robbed many people. Executed 1705 .............................................................................................................. 15 DICK MORRIS. Cunning and audacious swindler, executed 1706 ........................... 16 WILLIAM NEVISON Highwayman who robbed his fellows. Executed at York, 4th May 1684 ..................................................................................................................... 19 CAPTAIN AVERY Pirate who died penniless, having been robbed of his booty by merchants ..................................................................................................................... 24 CAPTAIN MARTEL Pirate ........................................................................................ 31 CAPTAIN TEACH alias BLACK BEARD, the Most Famous Pirate of all. ............... 33 CAPTAIN EDWARD ENGLAND Pirate .................................................................. 39 CAPTAIN CHARLES VANE. Pirate ......................................................................... 49 CAPTAIN JOHN RACKAM. -

and Thirty-Second Annual Reports I

- - - 1pj@..*</ ' , _xi : and Thirty-second Annual Reports I OF THE FOR THE OF THE FOR THE YEARS 1891 AND i892. BROOKLYN : PRINTED FOR THE COMRIISSIONERS. COMMISSIONERS. GEORGE V. BROWER, MARVIN CROSS, '. '. CHARLES H. LUSCOMB. COMMISSIONER. GEORGE V. BROWER. OFFICERS. Deputy Commissione~., MARVIN GROSS. Secretary, JOHN M. TOMPKINS. General Stcperimtemdent,, JOHN DE WOLF. Consulting Engineer, JOHN Y. GULYER. REPORT OF, TIIE FOR 1891. , DEPARTMICNTOF PARKS, Room 4, City Hall, BROOKLYN,January 31st, 1893. To the Hor~orablethe Common Council. GENTLEMEN:- The Commissioners of the Department of Parks hereby furnish your Honorable Body with a full report of their proceedings for the year 1891, embracing a detailed state- ment of their'receipts and expenditures for thpt time. The Commissioners of the Department of Parks would ~espectfullyreport that the Board of Estimate appropriated for the year 1891 $389,810 for Public Parks and Parkways, and $4,000 for Coney Island Concourse and Parade Ground. These amounts, together with $141,018.79 for balances over from 1889 and 1890, made the amount available for Park purposes for 1891, $534,828.79. Of thid amount there has been expended during the year 1891, $399,492.28, leaving a balance of $135,336.51, against which there are some bills and balances of con tracts on tstanding. Below please find a synopsis furnished by the Superin- 6 REPORT OF THE tendent of Parks of the work done by t'his Department during the year 1891. MAINTENANCE. The regular routine of maintenance consisted, as usual, in caring for drives, walks, bridle roads, lawns, trees and t I shrubs, propagating and caring for plants, flower beds, - drainage of land and drives, the general repairs of bnild- ings. -

Censorship of Publications Acts, 1929 to 1967

CENSORSHIP OF PUBLICATIONS ACTS, 1929 TO 1967 REGISTER OF PROHIBITED PUBLICATIONS 1. Alphabetical list of books prohibited on the ground that they were indecent or obscene (correct to 31st December, 2012). 2. Alphabetical list of books prohibited on the ground(s) that they were indecent or obscene and/or that they advocate the procurement of abortion or miscarriage or the use of any method, treatment or appliance for the purpose of such procurement (correct to 31st December, 2012). 3. Alphabetical list of prohibited Periodical Publications (as on 31st December, 2012). __________________________________ Published by the Censorship Board in accordance with directions of the Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform pursuant to sub-section (5) of section 16 of the Censorship of Publications Act, 1946 _______________________________________ DUBLIN: IMPORTANT The Register of prohibited books is in two Parts Part 1 contains particulars of books prohibited on the ground that they were indecent or obscene. The prohibition order in respect of any book named in Part 1 will cease to have effect on the 31st December following the twelfth anniversary of the date it was published in the Iris Oifigiúil (if it is not revoked by the Appeal Board before that). Where two or more prohibition orders refer to the same book, they will all cease to have effect when the one first made so ceases. Part II contains particulars of books prohibited on the ground(s) that they were indecent or obscene and/or that they advocate the procurement of abortion or miscarriage or the use of any method, treatment or appliance for the purpose of such procurement. -

TREASURE ISLAND the NOVEL and the MUSICAL 2 STUDY MATERIALS

Maine State Music Theatre Curtis Memorial Library, Topsham Public Library, and Patten Free Library present A STUDY GUIDE TO TREASURE ISLAND The NOVEL and the MUSICAL 2 STUDY MATERIALS TREASURE ISLAND: THE NOVEL Robert Louis Stevenson Page 3 Treasure Island in Literary History Page 5 Fun Facts About the Novel Page 6 Historical Context of the Novel Page 7 Adaptations of Treasure Island on Film and Stage Page 9 Treasure Island: Themes Page 10 Treasure Island: Synopsis of the Novel Page 11 Treasure Island: Characters in the Novel Page 13 Treasure Island: Glossary Page 15 TREASURE ISLAND A Musical Adventure: THE ROBIN & CLARK MUSICAL Artistic Statement Page 18 The Creators of the Musical Page 19 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Themes Page 20 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Synopsis & Songs Page 21 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Cast of Characters Page 24 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: World Premiere Page 26 Press Quotes Page 27 QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION Page 28 MSMT’s Treasure Island A Musical Adventure Page 29 3 TREASURE ISLAND: THE NOVEL ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, on November 13, 1850, to Thomas and Margaret Stevenson. Lighthouse design was his father's and his family's profession, so at age seventeen, he enrolled at Edinburgh University to study engineering, with the goal of following in the family business. Lighthouse design never appealed to Stevenson, though, and he began studying law instead. His spirit of adventure truly began to appear at this stage, and during his summer vacations he traveled to France to be around young writers and painters. -

Unit 8 Teacher Guide Grade 4 Treasure Island Grade 4 Unit 8

¬CKLA FLORIDA Unit 8 Teacher Guide Grade 4 Treasure Island Grade 4 Unit 8 Treasure Island Teacher Guide ISBN 978-1-68391-662-8 © 2015 The Core Knowledge Foundation and its licensors www.coreknowledge.org Revised and additional material © 2021 Amplify Education, Inc. and its licensors www.amplify.com All Rights Reserved. Core Knowledge Language Arts and CKLA are trademarks of the Core Knowledge Foundation. Trademarks and trade names are shown in this book strictly for illustrative and educational purposes and are the property of their respective owners. References herein should not be regarded as affecting the validity of said trademarks and trade names. Printed in the USA 01 BR 2020 G4_U07_TG_FL_20200909.indb 2 9/15/20 10:55 AM Grade 4 | Unit 8 Contents TREASURE ISLAND Introduction 1 Lesson 1 The Old Seadog 8 Core Connections (45 min.) Reading (45 min.) • Review Geography and History • Introduce the Reader • Introduce Pirates and Piracy • Introduce the Chapter • Introduce Nautical Terms • Read Chapter 1 • Chapter Discussion • Word Work: Driving Lesson 2 The Sea Chest 34 Reading (45 min.) Language (30 min.) Writing (15 min.) • Introduce the Chapter • Grammar: Modal Auxiliary Verbs • Introduce an Adventure • Read Chapter 2 • Morphology: Introduce Root bio Story • Chapter Discussion • Word Work: Ransack Lesson 3 Characters in Adventure Stories 64 Reading (45 min.) Writing (45 min.) • Review the Chapter • Choose a Setting • Read Chapter 2 • Plan a Character Sketch • Chapter Discussion • Word Work: Stun Lesson 4 A Real Adventure 74 Reading