Fashion and Jewelry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic Survey of North Sardinia 2014

Economic Survey of North Sardinia 2014 Economic Survey of North Sardinia 2014 PAGE 1 Economic Survey of North Sardinia 2014 Introduction Through the publication of the Economic Survey of North Sardinia, the Chamber of Commerce of Sassari aims to provide each year an updated and detailed study concerning social and economic aspects in the provinces of Sassari and Olbia-Tempio and, more generally, in Sardinia . This survey is addressed to all the entrepreneurs and institutions interested in the local economy and in the potential opportunities offered by national and foreign trade. Indeed, this analysis takes into account the essential aspects of the entrepreneurial activity (business dynamics, agriculture and agro-industry, foreign trade, credit, national accounts, manufacturing and services, etc…). Moreover, the analysis of the local economy, compared with regional and national trends, allows to reflect on the future prospects of the territory and to set up development projects. This 16th edition of the Survey is further enriched with comments and a glossary, intended to be a “guide” to the statistical information. In data-processing, sources from the Chamber Internal System – especially the Business Register – have been integrated with data provided by public institutions and trade associations. The Chamber of Commerce wishes to thank them all for their collaboration. In the last years, the Chamber of North Sardinia has been editing and spreading a version of the Survey in English, in order to reach all the main world trade operators. International operators willing to invest in this area are thus supported by this Chamber through this deep analysis of the local economy. -

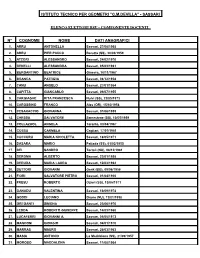

Istituto Tecnico Per Geometri "Gmdevilla"

ISTITUTO TECNICO PER GEOMETRI "G.M.DEVILLA" - SASSARI ELENCO ELETTORI RSU - COMPONENTE DOCENTI N° COGNOME NOME DATI ANAGRAFICI 1. ARRU ANTONELLA Sassari, 27/08/1968 2. ARRU PIER PAOLO Borutta (SS), 30/06/1959 3. ATZORI ALESSANDRO Sassari, 24/02/1970 4. BENELLI ALESSANDRA Sassari, 05/03/1961 5. BERGANTINO BEATRICE Ginevra, 10/11/1967 6. BRANCA PATRIZIA Sassari, 08/12/1958 7. CANU ANGELO Sassari, 27/01/1954 8. CAPITTA GIANCARLO Sassari, 09/07/1955 9. CARGIAGHE RITA FRANCESCA Nulvi (SS), 22/05/1973 10. CAROSSINO FRANCO Ales (OR), 15/10/1958 11. CESARACCIO GIOVANNA Sassari, 07/06/1955 12. CHESSA SALVATORE Semestene (SS), 10/05/1959 13. COLLAZUOL ANGELA Taranto, 03/04/1967 14. COSSU CARMELA Cagliari, 17/01/1951 15. CUCCURU MARIA NICOLETTA Sassari, 18/05/1971 16. DASARA MARIO Pattada (SS), 01/02/1955 17. DEI SANDRO Tortolì (NU), 06/12/1961 18. DEROMA ALBERTO Sassari, 23/01/1958 19. DERUDA MARIA LAURA Sassari, 12/03/1964 20. DETTORI GIOVANNI Genk (BG), 09/06/1958 21. FIORI SALVATORE PIETRO Sassari, 01/04/1955 22. FRESU ROBERTO Ozieri (SS), 13/05/1971 23. GANADU VALENTINA Sassari, 16/09/1974 24. GODDI LUCIANO Orune (NU), 13/01/1958 25. GREGANTI SIMONA Sassari, 23/06/1970 26. LEDDA ROBERTO GIUSEPPE Sassari, 14/03/1960 27. LUCAFERRI GIOVANNIGIUSEPPE A. Sassari, 05/05/1973 28. MANCONI GIORGIO Sassari, 04/01/1970 29. MARRAS MAURO Sassari, 26/03/1963 30. MASIA ANTONIO La Maddalena (SS), 21/09/1957 31. MOROSO MADDALENA Sassari, 11/08/1964 32. MURA ISABELLA VITTORIA Sassari, 27/01/1955 33. -

RPP 2015 2017 (.Pdf)

Comune di Porto Torres Provincia di Sassari Relazione Previsionale e Programmatica 2015 – 2017 Elaborazione a cura del Servizio P rogrammazione e controllo Indice 1. Le caratteristiche generali della popolazione, del territorio, dell’economia e dei servizi ............................ 4 1.1 - La situazione demografica ......................................................................................................................... 4 1.1.1 - Popolazione .................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1.2 Popolazione di 15 anni e oltre classificata per massimo titolo di studio conseguito e provincia - anno 2013 ..................................................................................................................................... 6 1.1.3 Porto Torres - Popolazione per età, sesso e stato civile al 31.12.2014 ........................................... 7 1.1.4 - Distribuzione della popolazione di Porto Torres per classi di età da 0 a 18 anni al 31.12.2014. ..... 8 1.1.5 - Cittadini stranieri Porto Torres ....................................................................................................... 9 1.1.6 – Indici demografici e struttura della popolazione dal 2002 al 2015 ............................................. 11 Indice di vecchiaia .................................................................................................................................... 12 Indice di dipendenza strutturale ............................................................................................................ -

CC026-2021 Fondazione "Sardegna Isola Del

COMUNE DI MOGORO COMUNU DE MÒGURU Provincia di Oristano Provincia de Aristanis DELIBERAZIONE DEL CONSIGLIO COMUNALE N. 26 del 31-05-2021 Oggetto: Fondazione "Sardegna Isola del Romanico" - Adesione del Comune di Mogoro quale Socio Fondatore. Il giorno trentuno maggio duemilaventuno, il Consiglio Comunale, convocato a norma di regolamento, si è riunito in seduta Pubblica in Prima convocazione con inizio alle ore 09:33, nell’aula consiliare del Municipio di Mogoro in via Leopardi n. 8, nel rigoroso rispetto di tutte le prescrizioni anti-contagio Covid-19. Dei Consiglieri assegnati sono presenti i Signori: Cau Donato P Lasi Susanna P Piras Federico P Maccioni Marco P Cotogno Alex A Melis Ettore A Serra Simone P Spanu Loredana P Serrenti Francesco P Pia Giovanni P Lai Andrea P Ghiani Mauro A Meloni Diana Sofia P risultano presenti n. 10 e assenti n. 3 Presiede la seduta il Sindaco Donato Cau Partecipa il Segretario Comunale Dott.ssa Cristina Corda Premesso che: - Le chiese costruite in stile romanico fra la metà dell’XI e gli inizi del XIV secolo rappresentano una parte importante del patrimonio storico monumentale della Sardegna. Esse si integrano nei contesti urbani e rurali arrivando a connotare in senso significativo il paesaggio storico e architettonico dell’Isola. -Le chiese romaniche della Sardegna si inseriscono a pieno titolo nel panorama architettonico europeo. La loro costruzione si deve alla volontà dei re (giudici), dei vescovi isolani, che finanziarono i cantieri edilizi, e dagli Ordini Monastici che si insediarono nell’Isola, nonché all’attività delle maestranze giunte dal continente italico ed europeo e radicatesi in terra sarda. -

The Product North Sardinia

GLAMOUR SARDINIA THE PRODUCT OF NORTH SARDINIA Camera di Commercio Industria Artigianato Agricoltura della Provincia di Sassari in collaboration with Assessorato al Turismo della Provincia di Sassari NEW OFFERS OFF SEASON FROM THE HEART OF THE MEDITERRANEAN The Product North Sardinia Edition 2003/2004 1 Camera di Commercio Industria Artigianato Agricoltura della provincia di Sassari in collaboration with l’Assessorato al Turismo della Provincia di Sassari GLAMOUR SARDINIA THE PRODUCT OF NORTH SARDINIA [COLOPHON] © 2003 “GLAMOUR SARDINIA – New offers OFF SEASON from the heart of the Mediterranean” Camera di Commercio Industria Artigianato Agricoltura della provincia di Sassari All rights reserved Project: Giuseppe Giaccardi Research and text: Andrea Zironi, Cristina Tolone, Michele Cristinzio, Lidia Marongiu, Coordination: Lidia Marongiu Press-office: Carmela Mudulu Translation in french: Luigi Bardanzellu, Beatrice Legras, Cristina Tolone, Omar Oldani Translation in german: Carmela Mudulu, Luca Giovanni Paolo Masia, Diana Gaias, Omar Oldani Translation in english: Christine Tilley, Vera Walker, Carla Grancini, David Brett, Manuela Pulina Production: Studio Giaccardi & Associati – Management Consultants – [email protected] We thank the following for their precious and indispensable collaboration: the Chairman’s office, Secretariat and technical staff of the Chamber of Commerce, Industry, Handicrafts and Agriculture for province of Sassari, the tourism assessor ship for the province of Sassari, D.ssa Basoli of the Sovrintendenza Archeologica di Sassari, the archaeology Graziano Capitta, the chairmen and councillors of all towns in North-Sardinia, the companies managing archaeological sites, the handicraftsmen and tourism- operators of North-Sardinia and all who have contributed with engagement and diligence to structure all the information in this booklet. -

Comune Di Mores

REL_SINT_PP_BORUTTA_2017 – REV. 3 COMUNE DI BORUTTA (SS) PIANO PARTICOLAREGGIATO CENTRO MATRICE: ZONA A2 RELAZIONE SINTETICA PER LA DIMOSTRAZIONE DEL RISPETTO DEGLI ARTICOLI 52 E 53 DELLE N.T.A. PPR 2006 Aprile 2015 Aggiornamento Settembre 2016 Aggiornamento Aprile 2017 REV. 3 – Novembre 2017 La presente relazione viene aggiornata con le osservazioni del Servizio Tutela del Paesaggio (vedere paragrafo 22). 0 – INQUADRAMENTO DI AREA VASTA: IL MEILOGU Borutta è al centro di quella regione storica da sempre definita “Logudoro” e in subordine appartiene alla sub-regione “Meilogu”, che – negli ultimi anni – ha preso il sopravvento. In altre parole, in passato, con il termine Logudoro ci si riferiva ad una ampia zona che andava da Monti (a est) fino a Bonorva e Semestene, oggi l’unione dei comuni del Logudoro comprende solo Ozieri, Nughedu, Pattada, Tula, Ardara e Mores, mentre l’unione dei comuni del Meilogu comprende Banari, Bessude, Siligo, Thiesi, Cheremule, Borutta, Bonnanaro, Torralba, Giave, Cossoine, Bonorva, Pozzomaggiore e Semestene. O.1 - Riportiamo, dal “Dizionario dei comuni della Sardegna”, C. Delfino Editore, alcune righe della voce “Logudoro”, redatta da Paolo Pulina: Quadro geografico In tutte le carte della Sardegna la scritta “Logudoro” incrocia la linea del tracciato della superstrada 131 tra Sassari e Cagliari all’altezza di una zona tra Banari e Siligo (a ovest) e Monte Santo (a est). Dal punto di vista geografico, l’orientamento più sicuro per inquadrare l’estensione territoriale della regione del Logudoro è offerto dal volume di Alberto Mori: “Sardegna” (Torino, UTET, 1975, seconda edizione riveduta e aggiornata, p. 209): “I nomi dei Giudicati hanno avuto fortuna diversa: quello medievale, e anche il nome di Logudoro, ha avuto una notevole persistenza nella parte costituente il cuore dell’antico Giudicato e cioè da Bonorva a Mores e da Pozzomaggiore fin verso Ploaghe, pur essendo qui più appropriato e usato il nome di Mejlogu. -

The Case of Sardinia

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Biagi, Bianca; Faggian, Alessandra Conference Paper The effect of Tourism on the House Market: the case of Sardinia 44th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Regions and Fiscal Federalism", 25th - 29th August 2004, Porto, Portugal Provided in Cooperation with: European Regional Science Association (ERSA) Suggested Citation: Biagi, Bianca; Faggian, Alessandra (2004) : The effect of Tourism on the House Market: the case of Sardinia, 44th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Regions and Fiscal Federalism", 25th - 29th August 2004, Porto, Portugal, European Regional Science Association (ERSA), Louvain-la-Neuve This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/116951 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

Curriculum Vitae

F ORMATO EUROPEO PER IL CURRICULUM VITAE INFORMAZIONI PERSONALI Nome SGARANGELLA ROSARIO Indirizzo Comune di Ozieri Via Vittorio Veneto 11 - Ozieri Telefono 079781234 Fax 079787376 E-mail [email protected] [email protected] Nazionalità Italiana Data di nascita 25.01.1960 ESPERIENZA LAVORATIVA • Date (da – a) In ruolo al Comune di Ozieri dal novembre 1982 Attualmente svolge le mansioni di Capo Servizio Sportello Unico Attività Produttive • Nome e indirizzo del datore di Comune di Ozieri – Via Vittorio Veneto 11 lavoro • Tipo di azienda o settore Settore Amministrativo • Tipo di impiego Capo Servizio Sportello Unico Attività Produttive Incarico di Posizione Organizzativa Pagina 1 - Curriculum vitae di [ SGARANGELLA Rosario ] • Principali mansioni e responsabilità Progetti di marketing territoriale e promozione e valorizzazione prodotti e risorse locali. Implementazione attività si semplificazione e innovazione nell’ambito dei procedimenti amministrativi inerenti alla realizzazione, all’ampliamento, alla cessazione, alla riattivazione, alla localizzazione e alla rilocalizzazione di impianti produttivi nell’ambito della riforma degli Sportelli Unici Attività Produttive. Progetto per l’avvio e le attività del Suap Associato del Logudoro pormosso dall’Unione dei Comuni del Logudoro. Coordinamento delle attività svolte nell’ambito del Progetto per il miglioramento della funzionalità dei Suap associati e delle azioni relative all’accreditamento dei Suap nelle piattaforme nazionali e regionali. Da febbraio a maggio 2012, ha curato in qualità di responsabile il progetto SUAP NET promosso dalla Regione, Ancitel e BIC Sardegna denominato ”I Suap come supporto al comparto produttivo delle zone interne del Nord Sardegna” per il supporto e la formazione del Suap associato del Meilogu (Thiesi, Banari, Bessude, Bonnanaro, Cheremule, Cossoine, Giave, Pozzomaggiore, Romana, Torralba, Siligo) + Borutta, Nule e Buddusò. -

Legenda Perimetri Forestali Gestiti E Oasi Permanenti Di Protezione Faunistica

470000 480000 490000 500000 510000 520000 530000 540000 550000 560000 570000 CALA SANTA MARIA 4570000 4570000 PORTO MASSIMO S P TERRAVECCHIA-PORTOQUADRO 9 CAPO TESTA 1 SANTA TERESA GALLURA STAZZO VILLA 3 LA FILETTA 5 S P a S VIGNA GRANDE r ENTE FORESTE DELLA SARDEGNA SANTA RE PARATA S 1 VALLE ERICA e RUONI 3 r 3 CALA FRANCESE LA MADDALENA bi p DIREZIONE GENERALE s CONCA VERDE SP a 114 C SERVIZIO TECNICO E DELLA PREVENZIONE PORTO POZZO PUNTA SARDEGNA Ufficio Pedologico - Cartografico - GIS 8 COSTA SERENA GIOVAN MARCO 9 PORTO POLLO Vignola - La Contessa P PALAU S 4560000 4560000 LI PINNENTI COLUCCIA ALTURA SAN PASQUALE CAPANNACCIA CAPO D'ORSO 7 1 P PULCHEDDU RENA MAJORE S LE SALINE LI LIERI BAJA SARDINIA LISCIA DI VACCA s i PORTO CERVO TANCA MANNA b Perimetri Forestali Gestiti VIGNOLA MARE 9 MUCCHI BIANCHI PORTOBELLO LA CONIA 5 P CALA BITTA S PANTOGIA GOLFO PEVERO e CHESSA BASSACUTENA CANNIGIONE SP90 3 1 ABBIADORI NARAGONI P ROMAZZINO 3 S CALA DI VOLPE Oasi Permanenti di Protezione Faunistica TAMBURU 3 4550000 4550000 GREULI 1 S SANTA TERESINA S SP115 9 4 CAPRICCIOLI P5 9 AGLIENTU S P ARZACHENA S SALONI S VACCAGGI P 7 MONTICANAGLIA LU MOCU 3 14 COSTA PARADISO SP CRISCIULEDDU COSTA PARADISO LUOGOSANTO 5 LU COLBU SAN PANTALEO 2 FALSAGGIU 1 PORTISCO S S TINNARI 7 42 CANNEDDI S S PORTO ROTONDO LA MARINEDDA CUGNANA VERDE SP 39 Lu Sfussatu ISOLA ROSSA MARINELLA Monti Di Cognu P137 GOLFO ARANCI PISCHINAZZA S 9 MARINELLA 5 P9 4540000 4540000 S PADULEDDA P SPIAGGIA BIANCA S SOLE RUIU SANT'ANTONIO DI GALLURA MONTE ROTU PUNTA PEDROSA 2 TRINITA' D'AGULTU -

COMMISSION DECISION of 2 May 2005 Approving the Plan for The

5.5.2005EN Official Journal of the European Union L 118/37 COMMISSION DECISION of 2 May 2005 approving the plan for the eradication of African swine fever in feral pigs in Sardinia, Italy (notified under document number C(2005) 1255) (Only the Italian text is authentic) (Text with EEA relevance) (2005/362/EC) THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, (6) The plan for the eradication of African swine fever in feral pigs, as submitted by Italy, has been examined and Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European found to comply with Directive 2002/60/EC. Community, (7) For the sake of transparency it is appropriate to set out Having regard to Council Directive 2002/60/EC of 27 June in this Decision the geographical areas where the eradi- 2002 laying down specific provisions for the control of cation plan is to be implemented. African swine fever and amending Directive 92/119/EEC as 1 regards Teschen disease and African swine fever ( ) and in (8) The measures provided for in this Decision are in particular Article 16(1) thereof, accordance with the opinion of the Standing Committee on the Food Chain and Animal Health, Whereas: HAS ADOPTED THIS DECISION: (1) African swine fever is present in feral pigs in the province of Nuoro, Sardinia, Italy. Article 1 (2) In 2004 a serious recrudescence of the disease has The plan submitted by Italy for the eradication of African swine occurred in Sardinia. Italy has in relation with this recru- fever in feral pigs in the area as set out in the Annex is descence reviewed the measures so far taken to eradicate approved. -

Profilo D'ambito

PROFILO D’AMBITO 1 Plus Alghero – Profilo d’ambito. A cura dell’Ufficio di Piano INDICE LA STRUTTURA DEL TERRITORIO - p.4 DATI E INDICATORI DEMOGRAFICI DI BASE - p.49 IL QUADROSOCIALE, SOCIOSANITARIO, EPIDEMIOLOGICO - p.66 IL SISTEMA DELL’OFFERTA DI SERVIZI E INTERVENTI - p.71 QUADRO DEI BISOGNI - p.75 L’ASCOLTO DEL TERRITORIO. I tavoli tematici - p.77 ALLEGATI - p.80 2 Plus Alghero – Profilo d’ambito. A cura dell’Ufficio di Piano 3 Plus Alghero – Profilo d’ambito. A cura dell’Ufficio di Piano LA STRUTTURA DEL TERRITORIO 4 Plus Alghero – Profilo d’ambito. A cura dell’Ufficio di Piano Caratteristiche geografiche. L’ambito territoriale di Figura 2 – Provincie della Sardegna pianure, zone vallive, coste miste alte-rocciose e basse-sabbiose riferimento del PLUS di Alghero, insiste sulla corredate da una discreta presenza di corsi d’acqua. Provincia di Sassari. Coincide con il Distretto Questa morfologia ha favorito indubbiamente lo sviluppo Sanitario di Alghero, situato nella sud-occidentale dell’insediamento umano fin dall’antichità, consentendo l’impianto di della Provincia e comprende 23 Comuni: Alghero, colture cerealicole e la destinazione a pascolo di considerevoli Banari, Bessude, Bonnanaro, Bonorva, Borutta, porzioni di territorio. Grazie a particolari condizioni ambientali e Cheremule, Cossoine, Giave, Ittiri, Mara, storiche, si rileva un legame inscindibile e forte tra uomo, territorio e Monteleone Rocca Doria, Olmedo, Padria, cultura, presentando un’alta densità di beni e siti d’interesse culturale Figura 3 - Collocazione Pozzomaggiore, Putifigari, ed ambientale, nonché una notevole ricchezza di tradizioni e geografica PLUS di Alghero (area verde) Romana, Semestene, peculiarità etno-culturali. -

N. Iscr. Nominativo Data Di Nascita Luogo Di

Regione Autonoma della Sardegna - Assessorato Turismo, Artigianato e Commercio Registro Regionale delle Guide Turistiche Allegato alla Det. N. 102 Del 03/02/2009 Data di Luogo di N. Iscr. Nominativo Residenza Indirizzo nascita nascita 960 Casti Annalisa 26/07/1977 Cagliari Cagliari Via Col de Chele 9 961 Congia Consuelo 04/101979 Cagliari Quartucciu Via Quartuc 137 962 Serpi Monica 26/07/1968 Guspini Capoterra Via Isonzo 30 963 Perisi Roberto 22/01/1964 Cagliari Alghero Loc. La Scaletta 9 964 Mudadu Daniela 26/04/1974 Lucerna Perfugas Via Roma 20 965 Decandia Caterina 19/09/1972 Sassari Perfugas Via D'Azeglio 1 966 Fois Martina 28/10/1975 Sassari Perfugas Via Vivaldi 14 967 Sini Eliana 25/05/1972 Sassari Perfugas Via Santa Maria 6 968 Pittalis Serafina 19/08/1972 Sassari Borutta Via della Libertà 21 Calvia Maria 969 Giovanna 28/01/1962 Torralba Torralba Via Santa croce 7 970 Dongu Silvia Regina 06/101969 Borutta Borutta Via E. Toti 12 971 Fiori Agnese 01/02/1959 Torralba Torralba Via Roma 49 972 Zichi Salvatora 01/04/1964 Torralba Torralba Via Carlo Felice 11 973 Marras Barbara 03/09/1972 Sassari Cheremule Via Roma 3 974 Deriu Francesca 29/09/1960 Torralba Torralba Via Chiesa 14 Regione Autonoma della Sardegna - Assessorato Turismo, Artigianato e Commercio Registro Regionale delle Guide Turistiche Allegato alla Det. N. 102 Del 03/02/2009 Data di Luogo di N. Iscr. Nominativo Residenza Indirizzo nascita nascita Via Can. Cossu Reg. 975 Bua Marilena 19/02/1973 Ozieri Ozieri Ippicchiu 1 976 Arru filomena 10/05/1965 Sassari Borutta Via E.