"A Kind of Construction in Light and Shade": an Analytical Dialogue with Recording Studio Aesthetics in Two Songs by Led Zeppelin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Midnight Special Songlist

west coast music Midnight Special Please find attached the Midnight Special song list for your review. SPECIAL DANCES for Weddings: Please note that we will need your special dance requests, (I.E. First Dance, Father/Daughter Dance, Mother/Son Dance etc) FOUR WEEKS in advance prior to your event so that we can confirm that the band will be able to perform the song(s) and that we are able to locate sheet music. In some cases where sheet music is not available or an arrangement for the full band is need- ed, this gives us the time needed to properly prepare the music and learn the material. Clients are not obligated to send in a list of general song requests. Many of our clients ask that the band just react to whatever their guests are responding to on the dance floor. Our clients that do provide us with song requests do so in varying degrees. Most clients give us a handful of songs they want played and avoided. Recently, we’ve noticed in increase in cli- ents customizing what the band plays and doesn’t play with very specific detail. If you de- sire the highest degree of control (allowing the band to only play within the margin of songs requested), we ask for a minimum of 100 requests. We want you to keep in mind that the band is quite good at reading the room and choosing songs that best connect with your guests. The more specific/selective you are, know that there is greater chance of losing certain song medleys, mashups, or newly released material the band has. -

Memphis Jug Baimi

94, Puller Road, B L U E S Barnet, Herts., EN5 4HD, ~ L I N K U.K. Subscriptions £1.50 for six ( 54 sea mail, 58 air mail). Overseas International Money Orders only please or if by personal cheque please add an extra 50p to cover bank clearance charges. Editorial staff: Mike Black, John Stiff. Frank Sidebottom and Alan Balfour. Issue 2 — October/November 1973. Particular thanks to Valerie Wilmer (photos) and Dave Godby (special artwork). National Giro— 32 733 4002 Cover Photo> Memphis Minnie ( ^ ) Blues-Link 1973 editorial In this short editorial all I have space to mention is that we now have a Giro account and overseas readers may find it easier and cheaper to subscribe this way. Apologies to Kees van Wijngaarden whose name we left off “ The Dutch Blues Scene” in No. 1—red faces all round! Those of you who are still waiting for replies to letters — bear with us as yours truly (Mike) has had a spell in hospital and it’s taking time to get the backlog down. Next issue will be a bumper one for Christmas. CONTENTS PAGE Memphis Shakedown — Chris Smith 4 Leicester Blues Em pire — John Stretton & Bob Fisher 20 Obscure LP’ s— Frank Sidebottom 41 Kokomo Arnold — Leon Terjanian 27 Ragtime In The British Museum — Roger Millington 33 Memphis Minnie Dies in Memphis — Steve LaVere 31 Talkabout — Bob Groom 19 Sidetrackin’ — Frank Sidebottom 26 Book Review 40 Record Reviews 39 Contact Ads 42 £ Memphis Shakedown- The Memphis Jug Band On Record by Chris Smith Much has been written about the members of the Memphis Jug Band, notably by Bengt Olsson in Memphis Blues (Studio Vista 1970); surprisingly little, however has got into print about the music that the band played, beyond general outline. -

Southeast Texas: Reviews Gregg Andrews Hothouse of Zydeco Gary Hartman Roger Wood

et al.: Contents Letter from the Director As the Institute for riety of other great Texas musicians. Proceeds from the CD have the History of Texas been vital in helping fund our ongoing educational projects. Music celebrates its We are very grateful to the musicians and to everyone else who second anniversary, we has supported us during the past two years. can look back on a very The Institute continues to add important new collections to productive first two the Texas Music Archives at SWT, including the Mike Crowley years. Our graduate and Collection and the Roger Polson and Cash Edwards Collection. undergraduate courses We also are working closely with the Texas Heritage Music Foun- on the history of Texas dation, the Center for American History, the Texas Music Mu- music continue to grow seum, the New Braunfels Museum of Art and Music, the Mu- in popularity. The seum of American Music History-Texas, the Mexico-North con- Handbook of Texas sortium, and other organizations to help preserve the musical Music, the definitive history of the region and to educate the public about the impor- encyclopedia of Texas tant role music has played in the development of our society. music history, which we At the request of several prominent people in the Texas music are publishing jointly industry, we are considering the possibility of establishing a music with the Texas State Historical Association and the Texas Music industry degree at SWT. This program would allow students Office, will be available in summer 2002. The online interested in working in any aspect of the music industry to bibliography of books, articles, and other publications relating earn a college degree with specialized training in museum work, to the history of Texas music, which we developed in cooperation musical performance, sound recording technology, business, with the Texas Music Office, has proven to be a very useful tool marketing, promotions, journalism, or a variety of other sub- for researchers. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

FOOL in the RAIN As Recorded by Led Zeppelin (From the 1979 Album "In Through the out Door")

FOOL IN THE RAIN As recorded by Led Zeppelin (from the 1979 Album "In Through The Out Door") Transcribed by Mister B. Words by John Paul Jones, Jimmy Page, Robert Plant Music by John Paul Jones, Jimmy Page, Robert Plant CC/G/G Am//C GG/B/B CC/G/G Dm//A EEmm//BB G G DDmm//AAVIVI EEmm/B/BVIIIVIII xx x 5fr. xxx 5fr. xxx 3fr. xxxo o xxx xxx 3fr. xx 3fr. xx x 6fr. xx x 8fr. VIIVII VII IXIX I I GG 7fr. G//B 7fr. AAmm//CC 9fr. F/FA/A 5fr. FF/A/A GG/D/D 7fr. F/FC/C 5fr. x xx xx x xx x xx x xxx xxx xxx A Intro P = 198 C/G Dm/AVI Em/BVIII Am/CIX G/BVII GVII Gtr III c c k c c j _ _c _c _ _ _ _ _ _ V V V V V 1 12 V V V V V k V V V V j I 8 V V V V V V V V V u u Gtr II w/dist. 0 1 1 3 5 5 3 3 T 1 3 3 5 5 5 3 3 3 0 2 2 4 5 5 4 4 4 A 5 B c c c V V V c c k k 12 V V V V V V f V V V V I 8 V V V V V V V V V V gV V V V Gtr V Piano arranged for guitar T 1 1 5 3 3 0 5 5 0 2 5 4 4 A 2 3 3 2 3 7 5 5 5 5 B 3 3 0 5 5 0 1 1 4 3 3 ©1979 Flames of Albion Music Inc. -

Arizona 500 2021 Final List of Songs

ARIZONA 500 2021 FINAL LIST OF SONGS # SONG ARTIST Run Time 1 SWEET EMOTION AEROSMITH 4:20 2 YOU SHOOK ME ALL NIGHT LONG AC/DC 3:28 3 BOHEMIAN RHAPSODY QUEEN 5:49 4 KASHMIR LED ZEPPELIN 8:23 5 I LOVE ROCK N' ROLL JOAN JETT AND THE BLACKHEARTS 2:52 6 HAVE YOU EVER SEEN THE RAIN? CREEDENCE CLEARWATER REVIVAL 2:34 7 THE HAPPIEST DAYS OF OUR LIVES/ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL PART TWO ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL PART TWO 5:35 8 WELCOME TO THE JUNGLE GUNS N' ROSES 4:23 9 ERUPTION/YOU REALLY GOT ME VAN HALEN 4:15 10 DREAMS FLEETWOOD MAC 4:10 11 CRAZY TRAIN OZZY OSBOURNE 4:42 12 MORE THAN A FEELING BOSTON 4:40 13 CARRY ON WAYWARD SON KANSAS 5:17 14 TAKE IT EASY EAGLES 3:25 15 PARANOID BLACK SABBATH 2:44 16 DON'T STOP BELIEVIN' JOURNEY 4:08 17 SWEET HOME ALABAMA LYNYRD SKYNYRD 4:38 18 STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN LED ZEPPELIN 7:58 19 ROCK YOU LIKE A HURRICANE SCORPIONS 4:09 20 WE WILL ROCK YOU/WE ARE THE CHAMPIONS QUEEN 4:58 21 IN THE AIR TONIGHT PHIL COLLINS 5:21 22 LIVE AND LET DIE PAUL MCCARTNEY AND WINGS 2:58 23 HIGHWAY TO HELL AC/DC 3:26 24 DREAM ON AEROSMITH 4:21 25 EDGE OF SEVENTEEN STEVIE NICKS 5:16 26 BLACK DOG LED ZEPPELIN 4:49 27 THE JOKER STEVE MILLER BAND 4:22 28 WHITE WEDDING BILLY IDOL 4:03 29 SYMPATHY FOR THE DEVIL ROLLING STONES 6:21 30 WALK THIS WAY AEROSMITH 3:34 31 HEARTBREAKER PAT BENATAR 3:25 32 COME TOGETHER BEATLES 4:06 33 BAD COMPANY BAD COMPANY 4:32 34 SWEET CHILD O' MINE GUNS N' ROSES 5:50 35 I WANT YOU TO WANT ME CHEAP TRICK 3:33 36 BARRACUDA HEART 4:20 37 COMFORTABLY NUMB PINK FLOYD 6:14 38 IMMIGRANT SONG LED ZEPPELIN 2:20 39 THE -

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020 1 REGA PLANAR 3 TURNTABLE. A Rega Planar 3 8 ASSORTED INDIE/PUNK MEMORABILIA. turntable with Pro-Ject Phono box. £200.00 - Approximately 140 items to include: a Morrissey £300.00 Suedehead cassette tape (TCPOP 1618), a ticket 2 TECHNICS. Five items to include a Technics for Joe Strummer & Mescaleros at M.E.N. in Graphic Equalizer SH-8038, a Technics Stereo 2000, The Beta Band The Three E.P.'s set of 3 Cassette Deck RS-BX707, a Technics CD Player symbol window stickers, Lou Reed Fan Club SL-PG500A CD Player, a Columbia phonograph promotional sticker, Rock 'N' Roll Comics: R.E.M., player and a Sharp CP-304 speaker. £50.00 - Freak Brothers comic, a Mercenary Skank 1982 £80.00 A4 poster, a set of Kevin Cummins Archive 1: Liverpool postcards, some promo photographs to 3 ROKSAN XERXES TURNTABLE. A Roksan include: The Wedding Present, Teenage Fanclub, Xerxes turntable with Artemis tonearm. Includes The Grids, Flaming Lips, Lemonheads, all composite parts as issued, in original Therapy?The Wildhearts, The Playn Jayn, Ween, packaging and box. £500.00 - £800.00 72 repro Stone Roses/Inspiral Carpets 4 TECHNICS SU-8099K. A Technics Stereo photographs, a Global Underground promo pack Integrated Amplifier with cables. From the (luggage tag, sweets, soap, keyring bottle opener collection of former 10CC manager and music etc.), a Michael Jackson standee, a Universal industry veteran Ric Dixon - this is possibly a Studios Bates Motel promo shower cap, a prototype or one off model, with no information on Radiohead 'Meeting People Is Easy 10 Min Clip this specific serial number available. -

Led Zeppelin Iii & Iv

Guitar Lead LED ZEPPELIN III & IV Drums Bass (including solos) Guitar Rhythm Guitar 3 Keys Vocals Backup Vocals Percussion/Extra 1 IMMIGRANT SONG (SD) Aidan RJ Dahlia Ben & Isabelle Kelly Acoustic (main part with high Low acoustic 2 FRIENDS (ENC) (CGCGCE) Mack notes) - Giulietta chords - Turner Strings - Ian Eryn Congas - James Synth (riffy chords) - (strummy chords) - (transitions from 3 CELEBRATION DAY (ENC) James Mack Jimmy Turner Slide - Aspen Friends) - ??? Giulietta Eryn SINCE I'VE BEEN LOVING YOU (Both Rhythm guitar 4 schools) Jaden RJ under solo - ??? Organ - ??? Kelly 5 OUT ON THE TILES (SD) Ethan Ben Dahlia Ryan Kelly Acoustic (starts at Electric solo beginning) - Aspen, (starts at 3:30) - Acoustic (starts at 6 GALLOWS POLE (ENC) Jimmy Mack James 1:05) - Turner Mandolin - Ian Eryn Banjo - Giulietta Electric guitar (including solo Acoustic and wahwah Acoustic main - Rhythm - 7 TANGERINE (SD) (First chord is Am) Ethan Aidan parts) - Isabelle Ben Dahlia Kelly Ryan g Electric slide - Acoustic - Aspen, Mandolin - 8 THAT'S THE WAY (ENC) (DGDGBD) RJ Turner Acoustic #2 - Ian Jimmy Giulietta Eryn Tambo - James Claps - Jaden, Acoustic - Shaker -Ethan, 9 BRON-YR-AUR STOMP (SD) (CFCFAC) Aidan Jaden Dahlia Acoustic - Ben Ryan Kelly Castanets - Kelly HATS OF TO YOU (ROY) HARPER Acoustic slide - 10 (CGCEGC) ??? 11 BLACK DOG (ENC) Jimmy Mack Giulietta James Aspen Eryn Giulietta Piano (starts after solo) - 12 ROCK AND ROLL (SD) Ethan Aidan Dahlia Isabelle Rebecca Ryan Tambo - Aidan Acoustic - Mandolin - The Sandy Jimmy, Acoustic Giulietta, Mandolin -

Press Kit—Winter NAMM 2017 Booth #4618

Press Kit—Winter NAMM 2017 Booth #4618 CONTACT: Jodi Anderson—Director, Communications & Product Marketing #learnteachplay P: 818-891-5999 x259 / F: 818-830-6259 / [email protected] / alfred.com/NAMM Mailing address: P.O. Box 10003 • Van Nuys, CA 91410-0003 • Street address: 16320 Roscoe Blvd., Suite 100 • Van Nuys, CA 91406 • Phone: 818.891.5999 • Fax: 818.830.6259 • Web: alfred.com Who We Are We help the world experience the joy of making music. Alfred Music, the leader in music education for 94 years, produces educational, reference, pop, and performance materials for teachers, students, professionals, and hobbyists spanning every musical instrument, style, and difficulty level. Alfred Music’s home office is located in Los Angeles, with domestic offices in Miami and New York, as well as offices around the world, including Germany, Singapore, and the United Kingdom. Since 1922, Alfred Music has been dedicated to helping people learn, teach, and play music. Alfred Music currently has over 150,000 active titles and represents a wide range of well-known publications—from methods like Alfred’s Basic Guitar, Alfred’s Basic Piano Library, Premier Piano Course, Sound Innovations, and Suzuki, to artists like Bruce Springsteen, Bruno Mars, Cole Porter, Carrie Underwood, Garth Brooks, Jimmy Buffett, George and Ira Gershwin, John Lennon, Katy Perry, Led Zeppelin, The Rolling Stones, and The Who, to brands like Harry Potter, Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, The Wizard of Oz, James Bond, Rolling Stone magazine, and Billboard. In addition to its own titles, Alfred Music distributes products from over 150 companies, including advance music, Belwin, Cengage Learning, Dover Publications, Drum Channel, Faber Music, Guitar World, Highland/Etling, Jamey Aebersold Jazz, Kalmus, MakeMusic, Penguin, Schaum Publications, and WEA. -

Led Zeppelin Download Album the Top 100 Best Selling Albums of All Time

led zeppelin download album The Top 100 Best Selling Albums of All Time. What’s the best selling album of all time? The answer might surprise you, based on certified sales by the RIAA. In 2018, The Eagles’ Their Greatest Hits (1971—1975) surpassed Michael Jackson’s Thriller as the best selling album of all time in the United States. Since that point, the lead has only widened. The Eagles album has now sold more than 38 million copies according to the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), thanks in part to continued touring across the United States and sustained interest on streaming platforms like Spotify. Their Greatest Hits (1971—1975) debuted in 1976 and included many of the group’s classics like “Take It Easy” and “Witchy Woman.” These sales figures compiled by the RIAA include disc and streaming sales. Thriller briefly overtook the Eagles compilation as the best selling album of all time in 2009 after Jackson’s death caused a surge in sales. But recent accusations against Jackson involving sexual assault may have softened sales for the pop superstar. Led Zeppelin IV (Remastered) Years after Led Zeppelin IV became one of the most famous albums in the history of rock music, Robert Plant was driving toward the Oregon Coast when the radio caught his ear. The music was fantastic: old, spectral doo-wop—nothing he’d ever heard before. When the DJ came back on, he started plugging the station’s seasonal fundraiser. Support local radio, he said—we promise we’ll never play “Stairway to Heaven.” Plant pulled over and called in with a sizable donation. -

A Tribute to Led Zeppelin from Hell's Kitchen Liner Notes

Led Blimpie: A Tribute to Led Zeppelin from Hell’s Kitchen Liner Notes Originally begun as a 3 song demo, this project evolved into a full-on research project to discover the recording styles used to capture Zeppelin's original tracks. Sifting through over 3 decades of interviews, finding the gems where Page revealed his approach, the band enrolled in “Zeppelin University” and received their doctorate in “Jimmy Page's Recording Techniques”. The result is their thesis, an album entitled: A Tribute to Led Zeppelin from Hell's Kitchen. The physical CD and digipack are adorned with original Led Blimpie artwork that parodies the iconic Zeppelin imagery. "This was one of the most challenging projects I've ever had as a producer/engineer...think of it; to create an accurate reproduction of Jimmy Page's late 60's/early 70's analog productions using modern recording gear in my small project studio. Hats off to the boys in the band and to everyone involved.. Enjoy!" -Freddie Katz Co-Producer/Engineer Following is a track-by-track telling of how it all came together by Co-Producer and Led Blimpie guitarist, Thor Fields. Black Dog -originally from Led Zeppelin IV The guitar tone on this particular track has a very distinct sound. The left guitar was played live with the band through a Marshall JCM 800 half stack with 4X12's, while the right and middle (overdubbed) guitars went straight into the mic channel of the mixing board and then into two compressors in series. For the Leslie sounds on the solo, we used the Neo Instruments “Ventilator" in stereo (outputting to two amps). -

MUSC 424 Led Zeppelin Spring 20

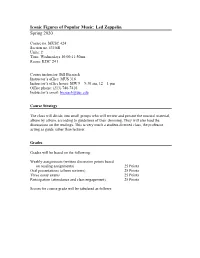

Iconic Figures of Popular Music: Led Zeppelin Spring 2020 Course no. MUSC 424 Section no. 47256R Units: 2 Time: Wednesdays 10:00-11:50am Room: KDC 241 Course instructor: Bill Biersach Instructor’s office: MUS 316 Instructor’s office hours: MW 9 – 9:30 am, 12 – 1 pm Office phone: (213) 740-7416 Instructor’s email: [email protected] Course Strategy The class will divide into small groups who will review and present the musical material, album by album, according to guidelines of their choosing. They will also lead the discussions on the readings. This is very much a student-directed class, the professor acting as guide rather than lecturer. Grades Grades will be based on the following: Weekly assignments (written discussion points based on reading assignments) 25 Points Oral presentations (album reviews) 25 Points Three essay exams 25 Points Participation (attendance and class engagement) 25 Points Scores for course grade will be tabulated as follows: Texts Required (available in paperback or Kindle format): Cole, Richard Stairway to Heaven: Led Zeppelin Uncensored Dey St. (An Imprint of William Morrow Publishers), It Books; Reprint Edition, 2002 ISBN-13: 978-0060938376 Kindle: Harper Collins e-books; Reprint edition, 2009 ASIN: B000TG1X70 Davis, Stephen Hammer of the Gods: The Led Zeppelin Saga Dey St. (An Imprint of William Morrow Publishers), It Books; Reprint Edition, 2008 ISBN: 978-0-06-147308-1 pk. Led Zeppelin Spring 2020 Schedule of Discussion Topics and Reading Assignments WEEK ALBUM DATE Stephen Davis Richard Cole Hammer of Stairway to Heaven: the Gods Led Zep Uncensored 1. Preliminaries Jan.