Trade Potential Between South Africa and Angola

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remembering Angola

The Creole Elite and the Rise of Angolan Proto-Nationalism: 1880-1910 Jacopo Corrado Abstract: The main purpose of this essay is to define the peculiarities of Angolan urban society and trace its evolution during the second half of the nineteenth century, a lapse of time marked by relative freedom—due to the economic crisis affecting Portugal from the definitive abolition of slavery and to the social and artistic progressive reformer impulse pro- moted by the Generation of 1870. This made possible the establishment in Luanda of lively journalistic activity and the production of a literary corpus—principally written by traders, soldiers, public officers, and landowners, born in Africa and tied both to their European and African origins, which witnessed the growth of a feeling of dissatisfaction destined to culminate in a heterogeneous set of open claims for autonomy or even independence. This article investigates a segment of Angolan history and literature with which non-Portuguese-speaking readers are generally not familiar, for its main purpose is to define the features and the literary production of what are conventionally called Creole elites, whose contribution to the early manifes- tations of dissatisfaction towards colonial rule was patent between 1880 and 1910, a period of renewed Portuguese commitment to its African colonies, but also of unrealised ambitions, economic crisis and socio-political upheaval in Angola and in Portugal itself. At that time, Angolan society was characterized by the presence of a semi- Portuguese Literary & Cultural Studies 15/16 (2010): 57-77. © University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. 58 PORTUGUESE LITERARY & CULTURAL STUDIES 15/16 urbanized commercial and administrative elite of Portuguese-speaking Creole families—white, black, some of mixed race, some Catholic and others Protestant, some old-established and others cosmopolitan—who were based in the main coastal towns. -

Angola in Perspective

© DLIFLC Page | 1 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Geography ......................................................................................................... 5 Country Overview ........................................................................................................... 5 Geographic Regions and Topographic Features ............................................................. 5 Coastal Plain ............................................................................................................... 5 Hills and Mountains .................................................................................................... 6 Central-Eastern Highlands .......................................................................................... 6 Climate ............................................................................................................................ 7 Rivers .............................................................................................................................. 8 Major Cities .................................................................................................................... 9 Luanda....................................................................................................................... 10 Huambo ..................................................................................................................... 11 Benguela ................................................................................................................... 11 Cabinda -

Angola Country Report

ANGOLA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION AND NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Angola October 2004 CONTENTS 1. Scope of the document 1.1 2. Geography 2.1 3. Economy 3.1 4. History Post-Independence background since 1975 4.1 Multi-party politics and the 1992 Elections 4.2 Lusaka Peace Accord 4.6 Political Situation and Developments in the Civil War September 1999 - February 4.13 2002 End of the Civil War and Political Situation since February 2002 4.19 5. State Structures The Constitution 5.1 Citizenship and Nationality 5.4 Political System 5.9 Presidential and Legislative Election Plans 5.14 Judiciary 5.19 Court Structure 5.20 Traditional Courts 5.23 UNITA - Operated Courts 5.24 The Effect of the Civil War on the Judiciary 5.25 Corruption in the Judicial System 5.28 Legal Documents 5.30 Legal Rights/Detention 5.31 Death Penalty 5.38 Internal Security 5.39 Angolan National Police (ANP) 5.40 Armed Forces of Angola (Forças Armadas de Angola, FAA) 5.43 Prison and Prison Conditions 5.45 Military Service 5.49 Forced Conscription 5.52 Draft Evasion and Desertion 5.54 Child Soldiers 5.56 Medical Services 5.59 HIV/AIDS 5.67 Angola October 2004 People with Disabilities 5.72 Mental Health Treatment 5.81 Educational System 5.82 6. Human Rights 6.A Human Rights Issues General 6.1 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.5 Newspapers 6.10 Radio and Television 6.13 Journalists 6.18 Freedom of Religion 6.25 Religious Groups 6.28 Freedom of Association and Assembly 6.29 Political Activists – UNITA 6.43 -

The Changing Face of the Zambia/Angola Border

Draft – not for citation The changing face of the Zambia/Angola border Paper prepared for the ABORNE Conference on ‘How is Africa Transforming Border Studies?’ Hosted by the School of Social Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa 10-14 September 2009 Oliver Bakewell International Migration Institute, University of Oxford, UK [email protected] August 2009 Abstract The establishment of the border between Zambia and Angola by the British and Portuguese at the beginning of the 20th century changed the nature of migration across the upper Zambezi region but did not necessarily diminish it. The introduction of the border was an essential part of the extension of colonial power, but at the same time it created the possibility of crossing the border to escape from one state’s jurisdiction to another: for example, to avoid slavery, forced labour, accusations of witchcraft, taxes and political repression. In the second half the 20th century, war in Angola stimulated the movement of many thousands of refugees into Zambia’s North‐Western Province. The absence of state structures on the Angolan side of the border and limited presence of Zambian authorities enabled people to create an extended frontier reaching deep into Angola, into which people living in Zambia could expand their livelihoods. This paper will explore some of the impacts of the end of the Angolan war in the area and will suggest that the frontier zone is shrinking as the ‘normal’ international border is being reconstructed. Draft – not for citation Draft – not for citation DRAFT – not for citation or circulation Introduction About a century ago, the British and Portuguese finally agreed on the line for the border between the northern portions of their colonies in Zambia and Angola,1 in the area known as the upper Zambezi. -

Angola's People

In the Eye of the Storm: Angola's People http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.crp20002 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org In the Eye of the Storm: Angola's People Author/Creator Davidson, Basil Publisher Anchor Books Anchor Press/Doubleday Date 1973-00-00 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Angola, Zambia, Congo, the Democratic Republic of the, Congo Coverage (temporal) 1600 - 1972 Rights By kind permission of Basil R. Davidson. Description This book provides both historical background and a description of Davidson's trip to eastern Angola with MPLA guerrilla forces. -

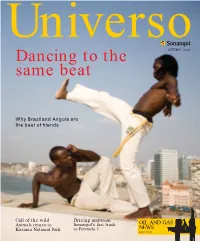

Dancing to the Same Beat

SU_19:Layout 1 1/9/08 10:22 Page 1 Universo Dancing to the AUTUMN 2008 same beat Why Brazil and Angola are the best of friends Call of the wild Driving ambition Animals return to Sonangol’s fast track OIL AND GAS Kissama National Park to Formula 1 NEWS pages 38-51 SU_19:Layout 1 1/9/08 10:23 Page 2 THE BIG PICTURE CONTENTS Name: Kikongo LANGUAGES Not forgotten: elephants in AKA: Quicongo, Congo, Kongo Kissama park, p24 Cabinda Spoken by: Bakongo Sonangol Department for Cabinda Number of speakers: 1m Communication & Image Name: Kimbundu Useful phrase: “How are you?” Director Mbanza translates as “Unam m’bote?” AKA: Quimbundo Soyo Congo Spoken by: Ambundu João Rosa Santos Numbers of speakers: 2m Zaire Corporate Communications Word fact: The name Angola Uíge Assistants comes from the Kimbundu ngola, Cristina de Novaes, meaning king Dundo Raimundo Vilares Uíge Bengo Caxito Lucapa Name: Umbundu Publisher Luanda Malanje AKA: Umbundo Sheila O’Callaghan Luanda Kwanza Norte Lunda Norte Spoken by: Ovimbundo Number of speakers: 4m Editor Ndalatando Alex Bellos Malanje Useful phrase: “What's Saurimo this?” translates as “Eci nye?” Art Director David Gould Lunda Sul Calulo Sub Editor Kwanza Sul Ron Gribble Sumbe Advertising Design Bernd Wojtczack Bié Luena Lobito Huambo Circulation Manager Benguela Kuito Matthew Alexander Huambo Group President Benguela John Charles Gasser Moxico Name: Tchokwé Project Consultant AKA: Ciokwe, Cokwe, Shioko, Nathalie MacCarthy Quioco, Djok, Tschiokloe istockphoto.com/David T Gomez Huíla Spoken by: Lunda-Tchokwé This magazine is produced for Menongue Number of speakers: Sonangol by Impact Media Letter from the editor 4 Lubango 850,000 Custom Publishing. -

Contents BRIEFS

17 February 2014 BRIEFS Africa • West African stock market gets boost Angola • Angola forex reserves fall to $31 bln in December Contents • Angola consumer inflation quickens 7.84% y/o/y in IN-DEPTH: January Botswana - African nations race to build sovereign funds 2 • Botswana to Sign Deal With Namibia to Develop - Mozambique economy: Quick View - Economy grows briskly Coal-Export Line quarter 2 Ghana - Angola economy: Quick View - Bond 3 • Fitch says its concerns about Ghana's economic - China and Japan’s complementary rivalry in Africa 3 imbalances growing - SOVEREIGN RATINGS 5 • Ghana risks overshooting its 11.5% 2014 inflation target INVESTMENTS 6 • Ghana consumer inflation rises to 13.8% in January Kenya BANKING • Equity uses credit rating to cut cost of loans for SMEs • Tullow Says Kenya Sees First Oil Exports as BANKS 8 ‘National Priority’ MARKETS 10 • Kenyan shilling eases versus dollar, further losses DEALS 11 seen FUNDS 12 Mozambique • Mozambique may raise coal tax: deputy mines TECH 13 minister • Mozambique c.bank governor says GDP growth could ENERGY 14 top 8.1% • Mozambique CPI slows to 3.16% year-on-year in MINING 16 January • S&P lowers Mozambique sovereign credit rating to B OIL & GAS 20 from B+ • Irish based miner Kenmare reschedules Mozambique debt INFRASTRUCTURE 22 Nigeria • The new directive on Cash-Reserve Ratio (CRR) on AGRIBUSINESS 23 public sector deposits by Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) took effect on 4th February 2014 TRADE 24 • Nigeria adds $550 million to sovereign wealth fund • Oil majors sell Nigerian stakes worth USD 6.5bn in MARKETS INDICATORS 26 2013 • Trading houses in race to buy oil majors' $3 bln UPCOMING EVENTS 27. -

The Genesis of the Brazilian Vernacular: Insights from the Indigenization of Portuguese in Angola

PAPIA 19, p. 93-122, 2009. ISSN 0103-9415 THE GENESIS OF THE BRAZILIAN VERNACULAR: INSIGHTS FROM THE INDIGENIZATION OF PORTUGUESE IN ANGOLA John Holm University of Coimbra [email protected] Abstract: This study uses the model of partial restructuring developed in Holm (2004), which compared the sociolinguistic history and synchronic structure of Brazilian Vernacular Portuguese (BVP) with that of four other non-creole vernaculars. Holm (2004) argued that the transmission of the European source languages from native to non-native speakers had led to partial restructuring, in which part of the source languages’ morphosyntax was retained, but a significant number of substrate and interlanguage features were introduced. It identified the linguistic processes that lead to partial restructuring, bringing into focus a key span on the continuum of contact-induced language change which has not previously been analyzed. The present study focuses more tightly on the genesis of BVP and attempts to reconstruct with greater precision the contribution of Bantu languages to its development in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries by comparing specific areas of its synchronic syntax to corresponding structures in Angolan Vernacular Portuguese, which is currently undergoing indigenization (Holm and Inverno 2005; Inverno forthcoming a, b). The main focus is on the verb phrase (verbal morphology, auxiliaries, negation, and non-verbal predicates) and the noun phrase (number and gender agreement, possessive constructions and pronouns). Key-words: Portuguese, partial restructuring, morphosyntax. 1. Introduction In Holm (2004) I developed a model for dealing with language varieties that have undergone only partial restructuring rather than full creolization. 94 JOHN HOLM This theoretical model was based on the results of a systematic comparison of the sociolinguistic history and synchronic structure of Brazilian Vernacular Portuguese (BVP) with that of four other non-creole vernaculars. -

Conservation and Sustainable Use of the Medicinal Leguminosae Plants from Angola

Conservation and sustainable use of the medicinal Leguminosae plants from Angola Silvia Catarino1,2, Maria Cristina Duarte3, Esperanca¸ Costa4, Paula Garcia Carrero3 and Maria M. Romeiras1,3 1 Linking Landscape, Environment, Agriculture and Food (LEAF), Instituto Superior de Agronomia (ISA), Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal 2 Forest Research Center (CEF), Instituto Superior de Agronomia (ISA), Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal 3 Centre for Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Changes (cE3c), Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal 4 Centro de Botânica, Universidade Agostinho Neto, Luanda, Angola ABSTRACT Leguminosae is an economically important family that contains a large number of medicinal plants, many of which are widely used in African traditional medicine. Angola holds a great socio-cultural diversity and is one of the richest floristic regions of the world, with over 900 native Leguminosae species. This study is the first to assess the medicinal uses of the legumes in Angola and provides new data to promote the conservation and the sustainable use of these unique resources. We document the ethnobotanical knowledge on Angola by reviewing the most important herbarium collections and literature, complemented by recent field surveys. Our results revealed that 127 native legume species have medicinal uses and 65% of them have other important uses by local populations. The species with most medicinal applications are Erythrina abyssinica, Bauhinia thonningii and Pterocarpus angolensis. The rich flora found in Angola suggests an enormous potential for discovery of new drugs with therapeutic value. However, the overexploitation and the indiscriminate collection of legumes for multiple uses such as forage, food, timber and medical uses, increases the Submitted 16 November 2018 threats upon the native vegetation. -

Immigrant Associations, Integration and Identity Angolan

IMISCOE sardinha This book sheds light on the integration processes and identity patterns of Angolan, DISSERTATIONS Brazilian and Eastern European communities in Portugal. It examines the privileged position that immigrant organisations hold as interlocutors between the communities they represent and various social service mechanisms operating at national and local levels. Through the collection of ethnographic data and the realisation of 110 interviews with community insiders and middlemen, culled over a year’s time, João Sardinha Immigrant Associations, Integration and Identity provides insight into how the three groups are perceived by their respective associations Immigrant Associations, and representatives. Following up on the rich data is a discussion of strategies of coping with integration and identity in the host society and reflections on Portuguese social and community services and institutions. Integration and Identity João Sardinha is a researcher at the Centre for the Study of Migrations and Intercultural Relations (cemri) at Universidade Aberta (Open University) in Lisbon. Angolan, Brazilian and Eastern European Communities in “This book makes a substantial contribution to our understanding of the role immigrant associations play in migrant integration processes and identity formation. João Sardinha provides rich new empirical evidence on Portuguese immigrant communities spanning three continents.” Portugal Maria Lucinda Fonseca, Director and Senior Researcher Centro de Estudos Geográficos, University of Lisbon joo sardinha