An Exploration of Harmony and Voice Leading in the Compositions of Chick Corea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE SHARED INFLUENCES and CHARACTERISTICS of JAZZ FUSION and PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014

COMMON GROUND: THE SHARED INFLUENCES AND CHARACTERISTICS OF JAZZ FUSION AND PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master in Jazz Performance and Pedagogy Department of Music 2020 Abstract Blunk, Joseph Michael (M.M., Jazz Performance and Pedagogy) Common Ground: The Shared Influences and Characteristics of Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock Thesis directed by Dr. John Gunther In the late 1960s through the 1970s, two new genres of music emerged: jazz fusion and progressive rock. Though typically thought of as two distinct styles, both share common influences and stylistic characteristics. This thesis examines the emergence of both genres, identifies stylistic traits and influences, and analyzes the artistic output of eight different groups: Return to Forever, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Miles Davis’s electric ensembles, Tony Williams Lifetime, Yes, King Crimson, Gentle Giant, and Soft Machine. Through qualitative listenings of each group’s musical output, comparisons between genres or groups focus on instances of one genre crossing over into the other. Though many examples of crossing over are identified, the examples used do not necessitate the creation of a new genre label, nor do they demonstrate the need for both genres to be combined into one. iii Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Part One: The Emergence of Jazz………………………………………………………….. 3 Part Two: The Emergence of Progressive………………………………………………….. 10 Part Three: Musical Crossings Between Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock…………….... 16 Part Four: Conclusion, Genre Boundaries and Commonalities……………………………. 40 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………. -

Download This List As PDF Here

QuadraphonicQuad Multichannel Engineers of 5.1 SACD, DVD-Audio and Blu-Ray Surround Discs JULY 2021 UPDATED 2021-7-16 Engineer Year Artist Title Format Notes 5.1 Production Live… Greetins From The Flow Dishwalla Services, State Abraham, Josh 2003 Staind 14 Shades of Grey DVD-A with Ryan Williams Acquah, Ebby Depeche Mode 101 Live SACD Ahern, Brian 2003 Emmylou Harris Producer’s Cut DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck David Alan David Alan DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Dire Straits Brothers In Arms DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Dire Straits Alchemy Live DVD/BD-V Ainlay, Chuck Everclear So Much for the Afterglow DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck George Strait One Step at a Time DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck George Strait Honkytonkville DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Sailing To Philadelphia DVD-A DualDisc Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Shangri La DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Mavericks, The Trampoline DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Olivia Newton John Back With a Heart DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Pacific Coast Highway Pacific Coast Highway DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Peter Frampton Frampton Comes Alive! DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Trisha Yearwood Where Your Road Leads DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Vince Gill High Lonesome Sound DTS CD/DVD-A/SACD Anderson, Jim Donna Byrne Licensed to Thrill SACD Anderson, Jim Jane Ira Bloom Sixteen Sunsets BD-A 2018 Grammy Winner: Anderson, Jim 2018 Jane Ira Bloom Early Americans BD-A Best Surround Album Wild Lines: Improvising on Emily Anderson, Jim 2020 Jane Ira Bloom DSD/DXD Download Dickinson Jazz Ambassadors/Sammy Anderson, Jim The Sammy Sessions BD-A Nestico Masur/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Kverndokk: Symphonic Dances BD-A Orchestra Anderson, Jim Patricia Barber Modern Cool BD-A SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2020 Patricia Barber Higher with Ulrike Schwarz Download SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2021 Patricia Barber Clique Download Svilvay/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Mortensen: Symphony Op. -

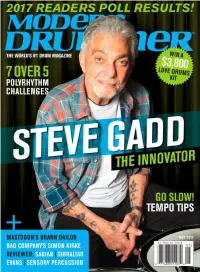

40 Steve Gadd Master: the Urgency of Now

DRIVE Machined Chain Drive + Machined Direct Drive Pedals The drive to engineer the optimal drive system. mfg Geometry, fulcrum and motion become one. Direct Drive or Chain Drive, always The Drummer’s Choice®. U.S.A. www.DWDRUMS.COM/hardware/dwmfg/ 12 ©2017Modern DRUM Drummer WORKSHOP, June INC. ALL2014 RIGHTS RESERVED. ROLAND HYBRID EXPERIENCE RT-30H TM-2 Single Trigger Trigger Module BT-1 Bar Trigger RT-30HR Dual Trigger RT-30K Learn more at: Kick Trigger www.RolandUS.com/Hybrid EXPERIENCE HYBRID DRUMMING AT THESE LOCATIONS BANANAS AT LARGE RUPP’S DRUMS WASHINGTON MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH CARLE PLACE CYMBAL FUSION 1504 4th St., San Rafael, CA 2045 S. Holly St., Denver, CO 11151 Veirs Mill Rd., Wheaton, MD 385 Old Country Rd., Carle Place, NY 5829 W. Sam Houston Pkwy. N. BENTLEY’S DRUM SHOP GUITAR CENTER HALLENDALE THE DRUM SHOP COLUMBUS PRO PERCUSSION #401, Houston, TX 4477 N. Blackstone Ave., Fresno, CA 1101 W. Hallandale Beach Blvd., 965 Forest Ave., Portland, ME 5052 N. High St., Columbus, OH MURPHY’S MUSIC GELB MUSIC Hallandale, FL ALTO MUSIC RHYTHM TRADERS 940 W. Airport Fwy., Irving, TX 722 El Camino Real, Redwood City, CA VIC’S DRUM SHOP 1676 Route 9, Wappingers Falls, NY 3904 N.E. Martin Luther King Jr. SALT CITY DRUMS GUITAR CENTER SAN DIEGO 345 N. Loomis St. Chicago, IL GUITAR CENTER UNION SQUARE Blvd., Portland, OR 5967 S. State St., Salt Lake City, UT 8825 Murray Dr., La Mesa, CA SWEETWATER 25 W. 14th St., Manhattan, NY DALE’S DRUM SHOP ADVANCE MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH HOLLYWOOD DRUM SHOP 5501 U.S. -

Musica Jazz Autore Titolo Ubicazione

MUSICA JAZZ AUTORE TITOLO UBICAZIONE AA.VV. Blues for Dummies MSJ/CD BLU AA.VV. \The \\metronomes MSJ/CD MET AA.VV. Beat & Be Bop MSJ/CD BEA AA.VV. Casino lights '99 MSJ/CD CAS AA.VV. Casino lights '99 MSJ/CD CAS AA.VV. Victor Jazz History vol. 13 MSJ/CD VIC AA.VV. Blue'60s MSJ/CD BLU AA.VV. 8 Bold Souls MSJ/CD EIG AA.VV. Original Mambo Kings (The) MSJ/CD MAM AA.VV. Woodstock Jazz Festival 1 MSJ/CD WOO AA.VV. New Orleans MSJ/CD NEW AA.VV. Woodstock Jazz Festival 2 MSJ/CD WOO AA.VV. Real birth of Fusion (The) MSJ/CD REA AA.VV. \Le \\grandi trombe del Jazz MSJ/CD GRA AA.VV. Real birth of Fusion two (The) MSJ/CD REA AA.VV. Saint-Germain-des-Pres Cafe III: the finest electro-jazz compilationMSJ/CD SAI AA.VV. Celebrating the music of Weather Report MSJ/CD CEL AA.VV. Night and Day : The Cole Porter Songbook MSJ/CD NIG AA.VV. \L'\\album jazz più bello del mondo MSJ/CD ALB AA.VV. \L'\\album jazz più bello del mondo MSJ/CD ALB AA.VV. Blues jam in Chicago MSJ/CD BLU AA.VV. Blues jam in Chicago MSJ/CD BLU AA.VV. Saint-Germain-des-Pres Cafe II: the finest electro-jazz compilationMSJ/CD SAI Adderley, Cannonball Cannonball Adderley MSJ/CD ADD Aires Tango Origenes [CD] MSJ/CD AIR Al Caiola Serenade In Blue MSJ/CD ALC Allison, Mose Jazz Profile MSJ/CD ALL Allison, Mose Greatest Hits MSJ/CD ALL Allyson, Karrin Footprints MSJ/CD ALL Anikulapo Kuti, Fela Teacher dont't teach me nonsense MSJ/CD ANI Armstrong, Louis Louis In New York MSJ/CD ARM Armstrong, Louis Louis Armstrong live in Europe MSJ/CD ARM Armstrong, Louis Satchmo MSJ/CD ARM Armstrong, Louis -

Downbeat.Com December 2014 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 . U.K DECEMBER 2014 DOWNBEAT.COM D O W N B E AT 79TH ANNUAL READERS POLL WINNERS | MIGUEL ZENÓN | CHICK COREA | PAT METHENY | DIANA KRALL DECEMBER 2014 DECEMBER 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Žaneta Čuntová Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Associate Kevin R. Maher Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, -

Jazz Quartess Songlist Pop, Motown & Blues

JAZZ QUARTESS SONGLIST POP, MOTOWN & BLUES One Hundred Years A Thousand Years Overjoyed Ain't No Mountain High Enough Runaround Ain’t That Peculiar Same Old Song Ain’t Too Proud To Beg Sexual Healing B.B. King Medley Signed, Sealed, Delivered Boogie On Reggae Woman Soul Man Build Me Up Buttercup Stop In The Name Of Love Chasing Cars Stormy Monday Clocks Summer In The City Could It Be I’m Fallin’ In Love? Superstition Cruisin’ Sweet Home Chicago Dancing In The Streets Tears Of A Clown Everlasting Love (This Will Be) Time After Time Get Ready Saturday in the Park Gimme One Reason Signed, Sealed, Delivered Green Onions The Scientist Groovin' Up On The Roof Heard It Through The Grapevine Under The Boardwalk Hey, Bartender The Way You Do The Things You Do Hold On, I'm Coming Viva La Vida How Sweet It Is Waste Hungry Like the Wolf What's Going On? Count on Me When Love Comes To Town Dancing in the Moonlight Workin’ My Way Back To You Every Breath You Take You’re All I Need . Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic You’ve Got a Friend Everything Fire and Rain CONTEMPORARY BALLADS Get Lucky A Simple Song Hey, Soul Sister After All How Sweet It Is All I Do Human Nature All My Life I Believe All In Love Is Fair I Can’t Help It All The Man I Need I Can't Help Myself Always & Forever I Feel Good Amazed I Was Made To Love Her And I Love Her I Saw Her Standing There Baby, Come To Me I Wish Back To One If I Ain’t Got You Beautiful In My Eyes If You Really Love Me Beauty And The Beast I’ll Be Around Because You Love Me I’ll Take You There Betcha By Golly -

Chick Corea Protagoniza Los Festivales De Jazz Con Un Disco Dedicado a España Euromoney Nos Ha Premiado Como Mejor Banco De España

Pag 01 ok.qxd 14/06/2019 12:23 PÆgina 1 EL CULTURAL1E. Venta conjunta e inseparable con El Mundo, y en librerías especializadas 21-27 de junio de 2019 www.elcultural.com Coetzee “El Quijote lo ha eclipsado todo” La tecla flamenca de Chick Corea Protagoniza los festivales de jazz con un disco dedicado a España Euromoney nos ha premiado como Mejor banco de España Porque creemos en una nueva forma de hacer banca más personal, digital y sencilla, para que puedas elegir cómo, cuándo y dónde relacionarte con nosotros. Y gracias a nuestra red de oficinas que trabaja para ofrecerte soluciones que mejoren tu día a día, y ayudarte a ti y a las empresas a progresar. Además, premio al Mejor banco de Europa Occidental bancosantander.es Pag 03 OK.qxd 14/06/2019 15:56 PÆgina 3 PRIMERA PALABRA L UIS MARÍA ANSON de la Real Academia Española Papell: “Villar Mir, personalidad universal” ntonio Papell ha escrito sición robustece, por cierto, la paña en el mundo. Desde hace mo, exigente hasta la médula, una espléndida biografía biografía escrita por Antonio cincuenta años, Villar Mir es inexorable en el juicio, erizante Ade Juan Miguel Villar Mir, Papell, que ha puesto, con total uno de los líderes destacados en el trabajo nuestro de cada empresario de espaldas cate- independencia, un espejo de- de la actividad empresarial es- día. Es la amabilidad con los dé- dralicias, orejas indulgentes, lante de la vida y la obra del pañola. Incluso sus detractores, biles, la mano tendida en apoyo andares de cirio pascual y voz gran ingeniero, del empresario que los tiene y son en ocasiones de los desfavorecidos. -

Rachel Agan Graduate Recital

Rachel Agan Acknowledgements percussion • I would like to thank my instructor and advisor, Dr. Brian Pfeifer, for all the knowledge and insight he’s passed down over the years. Graduate Recital Thank you for always pushing me to think critically in performance, education, and life. • Thank you to my lovely guest artist and human ray of sunshine, Mandy Moreno. Putting together our jazz set for this recital was easily my favorite part of the whole process! Collaborating with you was fun, easy, and educational. • I would like to thank my family and friends for providing a strong featuring support system as I pursue a career in music. Thank you for always pushing me to do more than I believe is possible. Mandy Moreno • Thank you to all the hardworking staff and faculty in the UND voice Music Department. Fostering an educational environment that meets expectedly high standards is a challenge in the middle of a pandemic, but you’re all succeeding. I see you and appreciate you. • Thank you to Dr. Cory Driscoll for coordinating the recording and live-streaming of this recital. • Thank you to every music teacher I’ve had in the past who has influenced the musician I am today. • Thank YOU for tuning in! Josephine Campbell Recital Hall This recital is in partial fulfillment of a Sunday, April 18th, 2021 Masters of Music: Percussion Performance. 2:00 pm UND.edu/music 701.777.2644 UND.edu/music 701.777.2644 Program Program Notes Rebonds Iannis Xenakis Rebonds (1987-9) Iannis Xenakis A (1922-2001) Xenakis was a Greek-French composer active in the late-20th century in Paris. -

Flamenco Jazz: an Analytical Study

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research John Jay College of Criminal Justice 2016 Flamenco Jazz: an Analytical Study Peter L. Manuel CUNY Graduate Center How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_pubs/306 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Journal of Jazz Studies vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 29-77 (2016) Flamenco Jazz: An Analytical Study Peter Manuel Since the 1990s, the hybrid genre of flamenco jazz has emerged as a dynamic and original entity in the realm of jazz, Spanish music, and the world music scene as a whole. Building on inherent compatibilities between jazz and flamenco, a generation of versatile Spanish musicians has synthesized the two genres in a wide variety of forms, creating in the process a coherent new idiom that can be regarded as a sort of mainstream flamenco jazz style. A few of these performers, such as pianist Chano Domínguez and wind player Jorge Pardo, have achieved international acclaim and become luminaries on the Euro-jazz scene. Indeed, flamenco jazz has become something of a minor bandwagon in some circles, with that label often being adopted, with or without rigor, as a commercial rubric to promote various sorts of productions (while conversely, some of the genre’s top performers are indifferent to the label 1). Meanwhile, however, as increasing numbers of gifted performers enter the field and cultivate genuine and substantial syntheses of flamenco and jazz, the new genre has come to merit scholarly attention for its inherent vitality, richness, and significance in the broader jazz world. -

FAKE BOOKS Catalog

2006 Music Dispatch FAKE BOOKS Catalog 8 BEGINNING FAKE BOOKS 27 BEST CHORD CHANGES 24 GUITAR FAKE BOOKS 25 JAZZ BIBLE SERIES 34 LYRIC COLLECTIONS 32 LYRIC LIBRARY 28 PAPERBACK SONGS 2 REAL BOOKS 26 REAL LITTLE FAKE BOOKS ORDER TODAY! 1-800-637-2852 www.musicdispatch.com 2 FAKE BOOKS The Real Books are the best-selling jazz books of all time. Since the 1970s, musicians have trusted these volumes to get them through every gig, night after night. The problem is that the books were illegally produced and distributed, without any regard to copyright law, or royalties paid to the composers who created these musical masterpieces. We are very proud to offer the first legitimate and legal editions of these books ever produced. You won’t even notice the difference, other than that all of the notorious errors have been fixed: the covers and typeface look the same, the song lists are nearly identical, and the prices for our editions are even more affordable than the originals! Every conscientious musician will appreciate that these books are now produced accurately and ethically, benefitting the songwriters that we owe for some of the greatest tunes of all time! THE REAL BOOK – VOLUME 1 SIXTH EDITION 400 songs, including: Afternoon in Paris • Agua De Beber (Water to Drink) • Alfie • All Blues • All of Me • All the Things You Are • Alright, Okay, You Win • Anthropology • April in Paris • Au Privave • Autumn in New York • Autumn Leaves • Bewitched • Black Coffee • Black Orpheus • Blue Bossa • Blue in Green • Bluesette • Body and Soul • Boplicity (Be -

Chick Corea Bio 2015 Chick Corea Has Attained Iconic Status in Music

Chick Corea Bio 2015 Chick Corea has attained iconic status in music. The keyboardist, composer and bandleader is a DownBeat Hall of Famer and NEA Jazz Master, as well as the fourth- most nominated artist in Grammy Awards history with 63 nods – and 22 wins, in addition to a number of Latin Grammys. From straight-ahead to avant-garde, bebop to jazz-rock fusion, children’s songs to chamber and symphonic works, Chick has touched an astonishing number of musical bases in his career since playing with the genre-shattering bands of Miles Davis in the late ’60s and early ’70s. Yet Chick has never been more productive than in the 21st century, whether playing acoustic piano or electric keyboards, leading multiple bands, performing solo or collaborating with a who’s who of music. Underscoring this, he has been named Artist of the Year twice this decade in the DownBeat Readers Poll. Born in 1941 in Massachusetts, Chick remains a tireless creative spirit, continually reinventing himself through his art. As The New York Times has said, he is “a luminary, ebullient and eternally youthful.” Chick’s classic albums as a leader or co-leader include Now He Sings, Now He Sobs (with Miroslav Vitous and Roy Haynes; Blue Note, 1968), Paris Concert (with Circle: Anthony Braxton, Dave Holland and Barry Altschul; ECM, 1971) and Return to Forever (with Return to Forever: Joe Farrell, Stanley Clarke, Airto Moreria and Flora Purim; ECM, 1972), as well as Crystal Silence(with Gary Burton; ECM, 1973), My Spanish Heart (Polydor/Verve, 1976), Remembering Bud Powell (Stretch, 1997) and Further Explorations (with Eddie Gomez and Paul Motian; Concord, 2012). -

Chick Corea – the Music Defies Words

By Allen Morrison PHOTO BY ARNE ROSTAD JAZZ ARTIST ‘The Music CHICK COREA Defies Words’ have no plan for this evening. So welcome to my living room.” Corea originals: the $amenco-inspired “Homage” and a previously unre- at’s how Armando “Chick” Corea opens a concert in Quebec, leased piano sonata called “e Moon.” as heard in the opening moments of Portraits (Stretch Records/ ese live albums are just two among Corea’s many recent projects. In Concord Jazz), his recent two-CD collection of live solo the past few years, he has toured and recorded with his current Latin-tinged performances. electric band e Vigil; formed the Grammy-winning Five Peace Band with ‘I Not to worry—he’s got this. John McLaughlin; reunited with his supergroup Return to Forever and He proceeds to unspool a program of favorite tunes by joined his RTF colleagues Stanley Clarke and Lenny White in an acoustic elonious Monk, Bill Evans, Stevie Wonder and Bud Powell; his improvi- trio; recorded Grammy-winning duos with Gary Burton and Béla Fleck; and, sations on compositions by Scriabin and Bartók; several original tunes from in his spare time, written and recorded !e Continents: Concerto For Jazz his album Children’s Songs ; and spontaneous musical “portraits” of volun- Quintet And Chamber Orchestra. teers from the audience at shows in Poland, Morocco, Lithuania and the Even the musicians who are closest to him wonder how he does it. Blade United States. Before each segment, Corea brings the audience into his con"- said it’s hard to separate the musician from the man.