NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Nature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plenary and Platform Abstracts

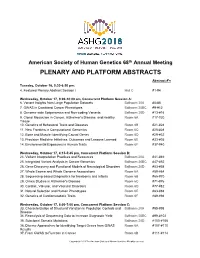

American Society of Human Genetics 68th Annual Meeting PLENARY AND PLATFORM ABSTRACTS Abstract #'s Tuesday, October 16, 5:30-6:50 pm: 4. Featured Plenary Abstract Session I Hall C #1-#4 Wednesday, October 17, 9:00-10:00 am, Concurrent Platform Session A: 6. Variant Insights from Large Population Datasets Ballroom 20A #5-#8 7. GWAS in Combined Cancer Phenotypes Ballroom 20BC #9-#12 8. Genome-wide Epigenomics and Non-coding Variants Ballroom 20D #13-#16 9. Clonal Mosaicism in Cancer, Alzheimer's Disease, and Healthy Room 6A #17-#20 Tissue 10. Genetics of Behavioral Traits and Diseases Room 6B #21-#24 11. New Frontiers in Computational Genomics Room 6C #25-#28 12. Bone and Muscle: Identifying Causal Genes Room 6D #29-#32 13. Precision Medicine Initiatives: Outcomes and Lessons Learned Room 6E #33-#36 14. Environmental Exposures in Human Traits Room 6F #37-#40 Wednesday, October 17, 4:15-5:45 pm, Concurrent Platform Session B: 24. Variant Interpretation Practices and Resources Ballroom 20A #41-#46 25. Integrated Variant Analysis in Cancer Genomics Ballroom 20BC #47-#52 26. Gene Discovery and Functional Models of Neurological Disorders Ballroom 20D #53-#58 27. Whole Exome and Whole Genome Associations Room 6A #59-#64 28. Sequencing-based Diagnostics for Newborns and Infants Room 6B #65-#70 29. Omics Studies in Alzheimer's Disease Room 6C #71-#76 30. Cardiac, Valvular, and Vascular Disorders Room 6D #77-#82 31. Natural Selection and Human Phenotypes Room 6E #83-#88 32. Genetics of Cardiometabolic Traits Room 6F #89-#94 Wednesday, October 17, 6:00-7:00 pm, Concurrent Platform Session C: 33. -

CD29 Identifies IFN-Γ–Producing Human CD8+ T Cells With

+ CD29 identifies IFN-γ–producing human CD8 T cells with an increased cytotoxic potential Benoît P. Nicoleta,b, Aurélie Guislaina,b, Floris P. J. van Alphenc, Raquel Gomez-Eerlandd, Ton N. M. Schumacherd, Maartje van den Biggelaarc,e, and Monika C. Wolkersa,b,1 aDepartment of Hematopoiesis, Sanquin Research, 1066 CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands; bLandsteiner Laboratory, Oncode Institute, Amsterdam University Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands; cDepartment of Research Facilities, Sanquin Research, 1066 CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands; dDivision of Molecular Oncology and Immunology, Oncode Institute, The Netherlands Cancer Institute, 1066 CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands; and eDepartment of Molecular and Cellular Haemostasis, Sanquin Research, 1066 CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands Edited by Anjana Rao, La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology, La Jolla, CA, and approved February 12, 2020 (received for review August 12, 2019) Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells can effectively kill target cells by producing therefore developed a protocol that allowed for efficient iso- cytokines, chemokines, and granzymes. Expression of these effector lation of RNA and protein from fluorescence-activated cell molecules is however highly divergent, and tools that identify and sorting (FACS)-sorted fixed T cells after intracellular cytokine + preselect CD8 T cells with a cytotoxic expression profile are lacking. staining. With this top-down approach, we performed an un- + Human CD8 T cells can be divided into IFN-γ– and IL-2–producing biased RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) and mass spectrometry cells. Unbiased transcriptomics and proteomics analysis on cytokine- γ– – + + (MS) analyses on IFN- and IL-2 producing primary human producing fixed CD8 T cells revealed that IL-2 cells produce helper + + + CD8 Tcells. -

Molecular Inhibitor of QSOX1 Suppresses Tumor Growth in Vivo Amber L

Author Manuscript Published OnlineFirst on October 1, 2019; DOI: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-19-0233 Author manuscripts have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication but have not yet been edited. Molecular Inhibitor of QSOX1 Suppresses Tumor Growth in vivo Amber L. Fifield1, Paul D. Hanavan2, Douglas O. Faigel3, Eduard Sergienko4, Andrey Bobkov4, Nathalie Meurice5, Joachim L. Petit5, Alysia Polito5, Thomas R. Caulfield6,7,8,9,10, Erik P. Castle11, John A. Copland12, Debabrata Mukhopadhyay13, Krishnendu Pal13, Shamit K. Dutta13, Huijun Luo14, Thai H. Ho14* and Douglas F. Lake1* *Co-corresponding authors 1School of Life Sciences, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA 2RenBio, Inc., New York, NY, USA 3Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Phoenix, AZ, USA 4Assay Development, Sanford Burnham Prebys Medial Discovery Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA 5Hematology/Oncology, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ, USA 6Department of Neuroscience, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL 32224 USA 7Mayo Graduate School, Neurobiology of Disease, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL 32224 USA 8Department of Cancer Biology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL 32224 USA 9Health Sciences Research, Division of Biomedical Statistics & Informatics, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL 32224 USA 10Center for Individualized Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL 32224 USA 11Department of Urology, Mayo Clinic, Phoenix, AZ, USA 12Department of Cancer Biology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL, USA 13Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL, USA 14Division of Hematology/Oncology, Mayo Clinic, Phoenix, AZ, USA Additional Information Contact Information: Thai H. Ho Mayo Clinic Arizona 5777 East Mayo Boulevard Phoenix, AZ 85054 Tel: 480-342-4800 Fax: 480-301-4675 Email: [email protected] Douglas F. -

QSOX1 ELISA Kit (Human) (OKCD00883) Lot# BJ02262021

QSOX1 ELISA Kit (Human) (OKCD00883) Lot# BJ02262021 Instructions for use For the quantitative measurement of QSOX1 in serum, plasma, tissue homogenates and other biological fluids. Variation between lots can occur. Refer to the manual provided with the kit. This product is intended for research use only. QSOX1 ELISA Kit (Human) (OKCD00883) – Lot# BJ02262021 Table of Contents 1. Background ................................................................................................................................. 2 2. Assay Summary .......................................................................................................................... 3 3. Storage and Stability ................................................................................................................... 3 4. Kit Components ........................................................................................................................... 3 5. Precautions.................................................................................................................................. 4 6. Required Materials Not Supplied ................................................................................................ 4 7. Technical Application Tips .......................................................................................................... 4 8. Reagent Preparation ................................................................................................................... 5 9. Sample Preparation ................................................................................................................... -

CD29 Identifies IFN-Γ–Producing Human CD8+ T Cells with an Increased Cytotoxic Potential

+ CD29 identifies IFN-γ–producing human CD8 T cells with an increased cytotoxic potential Benoît P. Nicoleta,b, Aurélie Guislaina,b, Floris P. J. van Alphenc, Raquel Gomez-Eerlandd, Ton N. M. Schumacherd, Maartje van den Biggelaarc,e, and Monika C. Wolkersa,b,1 aDepartment of Hematopoiesis, Sanquin Research, 1066 CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands; bLandsteiner Laboratory, Oncode Institute, Amsterdam University Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands; cDepartment of Research Facilities, Sanquin Research, 1066 CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands; dDivision of Molecular Oncology and Immunology, Oncode Institute, The Netherlands Cancer Institute, 1066 CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands; and eDepartment of Molecular and Cellular Haemostasis, Sanquin Research, 1066 CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands Edited by Anjana Rao, La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology, La Jolla, CA, and approved February 12, 2020 (received for review August 12, 2019) Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells can effectively kill target cells by producing therefore developed a protocol that allowed for efficient iso- cytokines, chemokines, and granzymes. Expression of these effector lation of RNA and protein from fluorescence-activated cell molecules is however highly divergent, and tools that identify and sorting (FACS)-sorted fixed T cells after intracellular cytokine + preselect CD8 T cells with a cytotoxic expression profile are lacking. staining. With this top-down approach, we performed an un- + Human CD8 T cells can be divided into IFN-γ– and IL-2–producing biased RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) and mass spectrometry cells. Unbiased transcriptomics and proteomics analysis on cytokine- γ– – + + (MS) analyses on IFN- and IL-2 producing primary human producing fixed CD8 T cells revealed that IL-2 cells produce helper + + + CD8 Tcells. -

Molecular Inhibitor of QSOX1 Suppresses Tumor Growth in Vivo Amber L

Published OnlineFirst October 1, 2019; DOI: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-19-0233 MOLECULAR CANCER THERAPEUTICS | SMALL MOLECULE THERAPEUTICS Molecular Inhibitor of QSOX1 Suppresses Tumor Growth In Vivo Amber L. Fifield1, Paul D. Hanavan2, Douglas O. Faigel3, Eduard Sergienko4, Andrey Bobkov4, Nathalie Meurice5, Joachim L. Petit5, Alysia Polito5, Thomas R. Caulfield6,7,8,9,10, Erik P. Castle11, John A. Copland12, Debabrata Mukhopadhyay13, Krishnendu Pal13, Shamit K. Dutta13, Huijun Luo14, Thai H. Ho14, and Douglas F. Lake1 ABSTRACT ◥ Quiescin sulfhydryl oxidase 1 (QSOX1) is an enzyme over- inhibitors, known as “SBI-183,” suppresses tumor cell growth in a expressed by many different tumor types. QSOX1 catalyzes the Matrigel-based spheroid assay and inhibits invasion in a mod- formation of disulfide bonds in proteins. Because short hairpin ified Boyden chamber, but does not affect viability of nonma- knockdowns (KD) of QSOX1 have been shown to suppress lignant cells. Oral administration of SBI-183 inhibits tumor tumor growth and invasion in vitro and in vivo, we hypothesized growth in 2 independent human xenograft mouse models of that chemical compounds inhibiting QSOX1 enzymatic activity renal cell carcinoma. We conclude that SBI-183 warrants further would also suppress tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis. exploration as a useful tool for understanding QSOX1 biology High throughput screening using a QSOX1-based enzymatic and as a potential novel anticancer agent in tumors that over- assay revealed multiple potential QSOX1 inhibitors. One of the express QSOX1. Introduction largest cohort (N ¼ 126), to our knowledge, of matched patient primary and renal cell carcinoma (RCC) metastases, we identified the Cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide and distant metastases upregulation of ECM-related genes in metastases relative to primary are the major cause of patient mortality. -

Lung Adenocarcinoma and Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cancer

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Lung adenocarcinoma and lung squamous cell carcinoma cancer classifcation, biomarker identifcation, and gene expression analysis using overlapping feature selection methods Joe W. Chen & Joseph Dhahbi* Lung cancer is one of the deadliest cancers in the world. Two of the most common subtypes, lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC), have drastically diferent biological signatures, yet they are often treated similarly and classifed together as non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). LUAD and LUSC biomarkers are scarce, and their distinct biological mechanisms have yet to be elucidated. To detect biologically relevant markers, many studies have attempted to improve traditional machine learning algorithms or develop novel algorithms for biomarker discovery. However, few have used overlapping machine learning or feature selection methods for cancer classifcation, biomarker identifcation, or gene expression analysis. This study proposes to use overlapping traditional feature selection or feature reduction techniques for cancer classifcation and biomarker discovery. The genes selected by the overlapping method were then verifed using random forest. The classifcation statistics of the overlapping method were compared to those of the traditional feature selection methods. The identifed biomarkers were validated in an external dataset using AUC and ROC analysis. Gene expression analysis was then performed to further investigate biological diferences between LUAD and LUSC. Overall, our method achieved classifcation results comparable to, if not better than, the traditional algorithms. It also identifed multiple known biomarkers, and fve potentially novel biomarkers with high discriminating values between LUAD and LUSC. Many of the biomarkers also exhibit signifcant prognostic potential, particularly in LUAD. Our study also unraveled distinct biological pathways between LUAD and LUSC. -

Quantitative Trait Loci Mapping of Macrophage Atherogenic Phenotypes

QUANTITATIVE TRAIT LOCI MAPPING OF MACROPHAGE ATHEROGENIC PHENOTYPES BRIAN RITCHEY Bachelor of Science Biochemistry John Carroll University May 2009 submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN CLINICAL AND BIOANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY December 2017 We hereby approve this thesis/dissertation for Brian Ritchey Candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy in Clinical-Bioanalytical Chemistry degree for the Department of Chemistry and the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY College of Graduate Studies by ______________________________ Date: _________ Dissertation Chairperson, Johnathan D. Smith, PhD Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, Cleveland Clinic ______________________________ Date: _________ Dissertation Committee member, David J. Anderson, PhD Department of Chemistry, Cleveland State University ______________________________ Date: _________ Dissertation Committee member, Baochuan Guo, PhD Department of Chemistry, Cleveland State University ______________________________ Date: _________ Dissertation Committee member, Stanley L. Hazen, MD PhD Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, Cleveland Clinic ______________________________ Date: _________ Dissertation Committee member, Renliang Zhang, MD PhD Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, Cleveland Clinic ______________________________ Date: _________ Dissertation Committee member, Aimin Zhou, PhD Department of Chemistry, Cleveland State University Date of Defense: October 23, 2017 DEDICATION I dedicate this work to my entire family. In particular, my brother Greg Ritchey, and most especially my father Dr. Michael Ritchey, without whose support none of this work would be possible. I am forever grateful to you for your devotion to me and our family. You are an eternal inspiration that will fuel me for the remainder of my life. I am extraordinarily lucky to have grown up in the family I did, which I will never forget. -

Systems Genetics in Diversity Outbred Mice Inform BMD GWAS and Identify Determinants of Bone Strength

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23649-0 OPEN Systems genetics in diversity outbred mice inform BMD GWAS and identify determinants of bone strength Basel M. Al-Barghouthi 1,2,8, Larry D. Mesner1,3,8, Gina M. Calabrese1,8, Daniel Brooks4, Steven M. Tommasini 5, Mary L. Bouxsein 4, Mark C. Horowitz5, Clifford J. Rosen 6, Kevin Nguyen1, ✉ Samuel Haddox2, Emily A. Farber1, Suna Onengut-Gumuscu 1,3, Daniel Pomp7 & Charles R. Farber 1,2,3 1234567890():,; Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) for osteoporotic traits have identified over 1000 associations; however, their impact has been limited by the difficulties of causal gene iden- tification and a strict focus on bone mineral density (BMD). Here, we use Diversity Outbred (DO) mice to directly address these limitations by performing a systems genetics analysis of 55 complex skeletal phenotypes. We apply a network approach to cortical bone RNA-seq data to discover 66 genes likely to be causal for human BMD GWAS associations, including the genes SERTAD4 and GLT8D2. We also perform GWAS in the DO for a wide-range of bone traits and identify Qsox1 as a gene influencing cortical bone accrual and bone strength. In this work, we advance our understanding of the genetics of osteoporosis and highlight the ability of the mouse to inform human genetics. 1 Center for Public Health Genomics, School of Medicine, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA. 2 Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics, School of Medicine, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA. 3 Department of Public Health Sciences, School of Medicine, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA. -

Genome-Wide Analysis Reveals Mucociliary Remodeling of the Nasal Airway Epithelium Induced by Urban PM2.5 Michael T

ORIGINAL RESEARCH Genome-Wide Analysis Reveals Mucociliary Remodeling of the Nasal Airway Epithelium Induced by Urban PM2.5 Michael T. Montgomery1, Satria P. Sajuthi1, Seung-Hyun Cho2, Jamie L. Everman1, Cydney L. Rios1, Katherine C. Goldfarbmuren1, Nathan D. Jackson1, Benjamin Saef1, Meghan Cromie1, Celeste Eng3, Vivian Medina4, Jennifer R. Elhawary3, Sam S. Oh3, Jose Rodriguez-Santana4, Eszter K. Vladar5,6, Esteban G. Burchard3,7, and Max A. Seibold1,5,8 1Center for Genes, Environment, and Health, and 8Department of Pediatrics, National Jewish Health, Denver, Colorado; 2RTI International, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina; 3Department of Medicine and 7Department of Bioengineering and Therapeutic Sciences, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California; 4Centro de Neumologıa´ Pediatrica, ´ San Juan, Puerto Rico; and 5Division of Pulmonary Sciences and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine and 6Department of Cell and Developmental Biology, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, Colorado ORCID IDs: 0000-0002-6748-2329 (M.T.M.); 0000-0001-9821-6667 (S.-H.C.); 0000-0002-1935-4672 (J.L.E.); 0000-0001-8774-7454 (K.C.G.); 0000-0003-3326-1680 (J.R.E.); 0000-0002-2815-6037 (S.S.O.); 0000-0002-4160-8894 (E.K.V.); 0000-0001-7475-2035 (E.G.B.); 0000-0002-8685-4263 (M.A.S.). Abstract mucus secretory expression program (.100 genes), which included transcriptional drivers of mucus metaplasia (SPDEF , FOXA3 fi Air pollution particulate matter 2.5 mm (PM2.5) exposure is and ). Exposure to a higher OE dose modi ed the associated with poor respiratory outcomes. Mechanisms underlying expression of 1,240 genes and further exacerbated expression PM2.5-induced lung pathobiology are poorly understood but likely responses observed at the moderate dose, including the mucus involve cellular and molecular changes to the airway epithelium. -

Proteolytic Processing of QSOX1A Ensures Efficient Secretion of A

Biochem. J. (2013) 454, 181–190 (Printed in Great Britain) doi:10.1042/BJ20130360 181 Proteolytic processing of QSOX1A ensures efficient secretion of a potent disulfide catalyst Jana RUDOLF*, Marie A. PRINGLE* and Neil J. BULLEID*1 *Institute of Molecular, Cellular and Systems Biology, College of Medical Veterinary and Life Sciences, Davidson Building, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, U.K. QSOX1 (quiescin sulfhydryl oxidase 1) efficiently catalyses the apparatus to yield soluble enzyme. As a consequence of this insertion of disulfide bonds into a wide range of proteins. The efficient processing, QSOX1 is probably functional outside the enzyme is mechanistically well characterized, but its subcellular cell. Also, QSOX1 forms a dimer upon cleavage of the C- location and the identity of its protein substrates remain ill- terminal domain. The processing of QSOX1 suggests a novel defined. The function of QSOX1 is likely to involve disulfide level of regulation of secretion of this potent disulfide catalyst formation in proteins entering the secretory pathway or outside and producer of hydrogen peroxide. the cell. In the present study, we show that this enzyme is efficiently secreted from mammalian cells despite the presence Key words: disulfide formation, proprotein convertase, proteolytic of a transmembrane domain. We identify internal cleavage sites processing, quiescin sulfhydryl oxidase 1 (QSOX1), sulfhydryl and demonstrate that the protein is processed within the Golgi oxidase. INTRODUCTION and can be secreted from a variety of tissues and is present in most bodily fluids [7,8]. The relative roles of QSOX1A and QSOX1 (quiescin sulfhydryl oxidase 1) is an enzyme that can QSOX1B have been difficult to determine because of the identical introduce disulfides into a wide range of proteins using molecular protein sequence of QSOX1B and part of the ectodomain of oxygen as an electron acceptor. -

Table S1. 103 Ferroptosis-Related Genes Retrieved from the Genecards

Table S1. 103 ferroptosis-related genes retrieved from the GeneCards. Gene Symbol Description Category GPX4 Glutathione Peroxidase 4 Protein Coding AIFM2 Apoptosis Inducing Factor Mitochondria Associated 2 Protein Coding TP53 Tumor Protein P53 Protein Coding ACSL4 Acyl-CoA Synthetase Long Chain Family Member 4 Protein Coding SLC7A11 Solute Carrier Family 7 Member 11 Protein Coding VDAC2 Voltage Dependent Anion Channel 2 Protein Coding VDAC3 Voltage Dependent Anion Channel 3 Protein Coding ATG5 Autophagy Related 5 Protein Coding ATG7 Autophagy Related 7 Protein Coding NCOA4 Nuclear Receptor Coactivator 4 Protein Coding HMOX1 Heme Oxygenase 1 Protein Coding SLC3A2 Solute Carrier Family 3 Member 2 Protein Coding ALOX15 Arachidonate 15-Lipoxygenase Protein Coding BECN1 Beclin 1 Protein Coding PRKAA1 Protein Kinase AMP-Activated Catalytic Subunit Alpha 1 Protein Coding SAT1 Spermidine/Spermine N1-Acetyltransferase 1 Protein Coding NF2 Neurofibromin 2 Protein Coding YAP1 Yes1 Associated Transcriptional Regulator Protein Coding FTH1 Ferritin Heavy Chain 1 Protein Coding TF Transferrin Protein Coding TFRC Transferrin Receptor Protein Coding FTL Ferritin Light Chain Protein Coding CYBB Cytochrome B-245 Beta Chain Protein Coding GSS Glutathione Synthetase Protein Coding CP Ceruloplasmin Protein Coding PRNP Prion Protein Protein Coding SLC11A2 Solute Carrier Family 11 Member 2 Protein Coding SLC40A1 Solute Carrier Family 40 Member 1 Protein Coding STEAP3 STEAP3 Metalloreductase Protein Coding ACSL1 Acyl-CoA Synthetase Long Chain Family Member 1 Protein