Frieze London 2019 | Booth C01 Flipper Stripper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1999 + Credits

1 CARL TOMS OBE FRSA 1927 - 1999 Lorraine’ Parish Church Hall. Mansfield Nottingham Journal review 16th Dec + CREDITS: All work what & where indicated. 1950 August/ Sept - Exhibited 48 designs for + C&C – Cast & Crew details on web site of stage settings and costumes at Mansfield Art Theatricaila where there are currently 104 Gallery. Nottm Eve Post 12/08/50 and also in Nottm references to be found. Journal 12/08/50 https://theatricalia.com/person/43x/carl- toms/past 1952 + Red related notes. 52 - 59 Engaged as assistant to Oliver Messel + Film credits; http://www.filmreference.com/film/2/Carl- 1953 Toms.html#ixzz4wppJE9U2 Designer for the penthouse suite at the Dorchester Hotel. London + Television credits and other work where indicated. 1957: + Denotes local references, other work and May - Apollo de Bellac - awards. Royal Court Theatre, London, ----------------------------------------------------- 57/58 - Beth - The Apollo,Shaftesbuy Ave London C&C 1927: May 29th Born - Kirkby in Ashfield 22 Kingsway. 1958 Local Schools / Colleges: March 3 rd for one week ‘A Breath of Spring. Diamond Avenue Boys School Kirkby. Theatre Royal Nottingham. Designed by High Oakham. Mansfield. Oliver Messel. Assisted by Carl Toms. Mansfield Collage of Art. (14 years old). Programme. Review - The Stage March 6th Lived in the 1940’s with his Uncle and Aunt 58/59 - No Bed for Bacon Bristol Old Vic. who ran a grocery business on Station St C&C Kirkby. *In 1950 his home was reported as being 66 Nottingham Rd Mansfield 1959 *(Nottm Journal Aug 1950) June - The Complaisant Lover Globe Conscripted into Service joining the Royal Theatre, London. -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pick, J.M. (1980). The interaction of financial practices, critical judgement and professional ethics in London West End theatre management 1843-1899. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/7681/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] THE INTERACTION OF FINANCIAL PRACTICES, CRITICAL JUDGEMENT AND PROFESSIONAL ETHICS IN LONDON WEST END THEATRE MANAGEMENT 1843 - 1899. John Morley Pick, M. A. Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the City University, London. Research undertaken in the Centre for Arts and Related Studies (Arts Administration Studies). October 1980, 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 4 Abstract 5 One. Introduction: the Nature of Theatre Management 1843-1899 6 1: a The characteristics of managers 9 1: b Professional Ethics 11 1: c Managerial Objectives 15 1: d Sources and methodology 17 Two. -

See a Full List of the National Youth

Past Productions National Youth Theatre '50s 1956: Henry V - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Toynbee Hall 1957: Henry IV Pt II - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Toynbee Hall 1957: Henry IV Pt II - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Worthington Hall, Manchester 1958: Troilus & Cressida - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Moray House Theatre, Edinburgh 1958: Troilus & Cressida - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith '60s 1960: Hamlet - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Tour of Holland. Theatre des Nations. Paris 1961: Richard II - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Apollo Theatre, Shaftesbury Avenue 1961: Richard II - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Ellen Terry Theatre. Tenterden. Devon 1961: Richard II - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @Apollo Theatre, Shaftesbury Avenue 1961: Henry IV Pt II - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Apollo Theatre, Shaftesbury Avenue 1961: Julius Caesar - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ British entry at Berlin festival 1962: Richard II - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Italian Tour: Rome, Florence, Genoa, Turin, Perugia 1962: Richard II - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Tour of Holland and Belgium 1962: Henry V - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Sadlers Wells 1962: Julius Caesar - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Sadlers Wells1962: 1962: Hamlet - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Tour for Centre 42. Nottingham, Leicester, Birmingham, Bristol, Hayes -

From Peter Brook: a Biography by Michael Kustow, to Be Published by St

From Peter Brook: A Biography by Michael Kustow. Copyright by the author. To be published by St. Martin's Press in March 2005. Chronology of Plays and Films of Peter Brook Note: In this chronology, plays appear in the year and at the theatre in which they opened, films appear in the year in which they were shot. 1943 Doctor Faustus, Torch Theatre, London 1944 Film: A Sentimental Journey 1945 The Infernal Machine, Jean Cocteau; at Chanticleer Theatre Club, London Man and Superman, Shaw; King John, Shakespeare; The Lady from the Sea, Ibsen; at Birmingham Repertory Theatre 1946 Love's Labour's Lost, Shakespeare; Stratford-upon-Avon The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoevsky; Lyric Theatre, London Vicious Circle, Jean-Paul Sartre; Arts Theatre, London 1947 Romeo and Juliet, Shakespeare; Stratford-upon-Avon The Respectful P . ., Jean-Paul Sartre; Lyric Theatre, London 1948 La Bohème, Puccini; Covent Garden, London Boris Godunov, Mussorgsky; Covent Garden, London The Olympians, Arthur Bliss; Covent Garden, London Salome, Richard Strauss; Covent Garden, London Le Nozze di Figaro, Mozart; Covent Garden, London 1949 Dark of the Moon, Howard Richardson and William Berney; Lyric Theatre Hammersmith, London 1950 Ring Round the Moon, Jean Anouilh; Globe Theatre, London Measure for Measure, Shakespeare; Stratford-upon-Avon The Little Hut, André Roussin; Lyric Theatre, London 1951 Mort d'un commis voyageur (Death of a Salesman), Arthur Miller; Théâtre National, Brussels Penny for a Song, John Whiting; Haymarket Theatre, London The Winter's Tale, Shakespeare; -

Illegitimate Theatre in London, –

ILLEGITIMATE THEATRE IN LONDON, – JANE MOODY The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge , UK www.cup.cam.ac.uk West th Street, New York, –, USA www.cup.org Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne , Australia Ruiz de Alarcón , Madrid, Spain © Jane Moody This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Monotype Baskerville /. pt System QuarkXPress™ [] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Moody, Jane. Illegitimate theatre in London, ‒/Jane Moody. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. . Theater – England – London – History – th century. Theater – England – London – History – th century. Title. .6 Ј.Ј–dc hardback Contents List of illustrations page ix Acknowledgements xi List of abbreviations xiii Prologue The invention of illegitimate culture The disintegration of legitimate theatre Illegitimate production Illegitimate Shakespeares Reading the theatrical city Westminster laughter Illegitimate celebrities Epilogue Select bibliography Index vii Illustrations An Amphitheatrical Attack of the Bastile, engraved by S. Collings and published by Bentley in . From the Brady collection, by courtesy of the Governing Body of Christ Church, Oxford. page The Olympic Theatre, Wych Street, by R.B. Schnebbelie, . By permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library. Royal Coburg Theatre by R.B. Schnebbelie, . By permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library. Royal Circus Theatre by Thomas Rowlandson and Augustus Pugin, published by Ackermann in . -

Cultural Mobility, Networks, and Theatre the Stagings of Ibsen’S Gengangere (Ghosts) in Berlin, Paris, London, Moscow, New York, and Budapest Between 1889 and 1908

NORDIC THEATRE STUDIES Vol. 32, No. 2. 2020, 6-25 Cultural Mobility, Networks, and Theatre The Stagings of Ibsen’s Gengangere (Ghosts) in Berlin, Paris, London, Moscow, New York, and Budapest between 1889 and 1908 ZOLTÁN IMRE ABSTRACT The Budapest premiere of Henrik Ibsen’s Kísértetek (Gengangere) was on 17 October 1908 by the Thália Társaság, a Hungarian independent theatre. Though banned earlier, by 1908, Ibsen’s text had already been played all over Europe. Between 1880 and 1908, the search of IbsenStage indicates 402 records, but probably the actual performance number was higher. The popularity of the text can be seen in the fact that all the independent theatres staged it, and most of the famous and less famous travelling companies and travelling stars also kept it in their repertoires. Though, usually, the high-artistic independent and the commercial international and regional travelling companies are treated separately, here, I argue for their close real and/or virtual interconnections, creating such a theatrical and cultural network, in which the local, the regional, the national, and the transnational interacted with and were influenced by each other. At the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, such interaction among different forces and agents on different levels was one of the special features of cultural mobility (Greenblatt) which characterized intercultural theatre culture, existing in Europe and America, and extending its influence almost all over the globe. KEYWORDS Intercultural theatre, touring, theatre historiography, transnationalism, national paradigm, theatrical networks, cultural mobility, independent theatre movement, Théâtre Libre, Freie Bühne, Independent Theatre Society, Московский Художественный театр (МХАТ), Thália Társaság. -

Almeida Theatre and Sonia Friedman Productions by Henrik Ibsen Season Sponsor: Adapted and Directed by Richard Eyre

BAM 2015 Winter/Spring Season #IbsensGhosts Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer Ghosts BAM Harvey Theater Apr 11, 18, 25, May 2 at 2pm Apr 7—11, 14—18, 21—25, 28—30, May 1 & 2 at 7:30pm Apr 5, 12, 19, 26, May 3 at 3pm Running time: 90 minutes, no intermission Almeida Theatre and Sonia Friedman Productions By Henrik Ibsen Season Sponsor: Adapted and directed by Richard Eyre Design by Tim Hatley Lighting by Peter Mumford Sound by John Leonard BAM 2015 Theater Sponsor Casting by Cara Beckinsale CDG Leadership support for BAM’s presentation of Ghosts Associate director Elena Araoz provided by Betsy and Ed Cohen/Areté Foundation With Lesley Manville, Billy Howle, Will Keen, Leadership support for Scandinavian programming Brian McCardie, Charlene McKenna provided by The Barbro Osher Pro Suecia Foundation Major support for theater at BAM provided by: The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation The Francena T. Harrison Foundation Trust Stephanie & Timothy Ingrassia Donald R. Mullen Jr. The Fan Fox & Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, Inc. The Morris and Alma Schapiro Fund The Shubert Foundation, Inc. The SHS Foundation Cast Lesley Manville Billy Howle Will Keen Brian McCardie Charlene McKenna Ghosts CAST, IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE Regina Engstrand Charlene McKenna Jacob Engstrand Brian McCardie Pastor Manders Will Keen Helene Alving Lesley Manville Oswald Alving Billy Howle Adapted and directed by Richard Eyre Production manager Simon Sturgess Design by Tim Hatley Costume supervisor Rachel Woodhouse Lighting by Peter Mumford Wig creator/Hair designer Angela Cobbin Sound by John Leonard Company stage manager Laura Draper Casting by Cara Beckinsale CDG Deputy stage manager Jenefer Tait Associate director Elena Araoz Production electrician Stephen Andrews Literal translator Charlotte Barslund Production photography Hugo Glendinning American stage manager R. -

Soho and Its Associations

93/06/90 11:42 805 9614676 SRLF MATERIAL PAGING REQUE PLEASE PPTMT ALL INFORMATION SRLF ACCESSION NUMBER OR SRLF C To Request a fiaok Fill In the Author; Title; \K Publisher : To Request a P periodical Title: Volume : Article Author: Article Title: !) PARK STREET, BRISTOL UCSB ILL ->-*- SRLF 12)001/001 UC SANTA BARBARA I Office Use: Date Published: Fill in the Following pages J9SO SOHO AND ITS ASSOCIATIONS. SOHO AND ITS ASSOCIATIONS, Historical, Literary, & Artistic. EDITED FROM THE MSS. OF THE LATE E. F. RIMBAULT, LL.D., F.S.A., BY GEORGE CLINCH. LONDON : DULAU & CO., 37 SOHO SQUARE, W. 1895. PREFACE. THE project of writing a History of Soho was long con- templated by the late Dr. Rimbault, and the collecting of materials for the purpose occupied his attention for some years. Those materials, largely consisting of rough notes gathered from a variety of sources, which form the bulk of the present volume, it has been the editor's somewhat difficult task to for and he takes this prepare publication ; opportunity of offering his sincerest thanks to those friends who have rendered him assistance in the work. G. C. ADDISCOMBE, SURRET, May, 1895. 2055804 CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. SOHO FIELDS. PAGE A'gas's map of London Early condition of the Soho Fields The village of St. Giles Increase ofpopulation and new buildings Proclama- tions prohibiting the erection of new buildings Origin and meaning ' of the name Soho' Hare-hunting and Fox-hunting at Soho Early references to Soho . i CHAPTER II. THE BUILDING OF SOHO. The Sobo Fields granted to the Earl of St. -

Copyri Ght by P H I L I P Alan Macomber

Copyri ght by Philip Alan Macomber 1959 THE ICONOGRAPHY OF LONDON THEATRE AUDITORIUM ARCHITECTURE, 1660-1900 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillm ent of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By P hilip Alan Macomber, B. A., n. A. The Ohio State University 1959 Approved by: Advi ser Department of Speech ACKNOWLEDGMENTS At this point in any study it is customary to acknowledge the moral and material assistance given by various individuals to an author. I, of course, am most grateful to my many friends who have helped make th is work possible. However, my deepest appreciation must go to The Ohio State University Theatre Collection which pointed out the potential or this study to me and then helped provide much of the pictorial evidence necessary for the realization of this project. Through the unique organizational concept of this Collection, the doors of the major libraries all over the world were opened to me, materials heretofore unavailable except to traveling scholars were placed at my disposal. This is more than just the mere accumulation of a few items on microfilm, this Theatre Collection represents an organized approach in a field of essentially disorganized material. The Ohio State University Theatre Collection could never have been without the understanding guidance of its Director, John H. McDowell. To Dr. McDowell, for the foresight and stamina necessary to the creation of The Ohio State University Theatre Collection, a word of thanks from a student. P h ilip A. Macomber Columbus, Ohio, 1959 I I TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. -

Trial by Jury

Principals Sale Gilbert & Sullivan Society We are delighted to announce that our Judge Usher next main production will be HMS proudly present Bob Wardle Tony Noden Pinafore and The Zoo. The latter has never been performed by the Society. Plaintiff Defendant 25th - 30th April 2007 Helen Fieldsend Paul Richmond At the: Garrick Theatre, Altrincham Dr Daly If you would like to be kept up to Foreman of the jury Council date of future performances the why not join our mailing list? (see John Matthias John Elliot below) Trial By Jury Plaintiffs mother Plaintiffs Father June Parr Dave Hunt Lesley Stockley-Roberts Anna Murgatroyd If you would like to become more closely involved with the Society, you may like to become a Member or a Patron. Becoming a Patron Our Patrons receive up to date information of the Society’s programme of concerts and other events and an opportunity Janice Rendel Denise Tyler to book their tickets in advance. Becoming a Member If you want to join the Society we are always looking for new members to sing or to help behind the scenes. Bea Schouten Mailing List If you would like to be placed on our mailing list or receive Chorus information about the society and/or future events there are Bridesmaids several ways to contact us. Anna Murgatroyd, Lesley Stock-Roberts, Janice Rendel, By Mail Bea Schouten, Denise Tyler. You can contact the Chairman by writing to: Jury Tony Noden, 45, The Circuit, Cheadle Hulme, Cheshire, Directed by Eileen Jackson Edna Lawson, Rachel Patterson, Brenda Thompson, Ceri Wilde, SK8 7LF Ken Brook, Eric Brunt, Mathew Callaghan, John Dickson, Martin Gude, 29th October 2006 Tony Topping, Phil Sweet. -

Online Finding

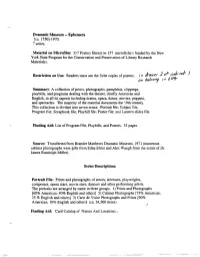

Dramatic Museum -- Ephemera [ca. 1750]-1970. 7 series. Material on Microfilm: 317 Posters filmed on 157 microfiche ( funded by the New York State Program for the Conservation and Preservation of Library Research Materials). Restriction on Use: Readers must use the fiche copies of posters, in draper A fj^f/ on bctlcotg ,o d^r Summary: A collection of prints, photographs, pamphlets, clippings, playbills, and programs dealing with the theater, chiefly American and English, in all its aspects including drama, opera, dance, movies, puppets, and spectacles. The majority of the material documents the 19th century. This collection is divided into seven series: Portrait file; Subject file; Program file; Scrapbook file; Playbill file; Poster file; and Lantern slides file. Finding Aid: List of Program File, Playbills, and Posters. 33 pages. Source: Transferred from Brander Matthews Dramatic Museum, 1971 (numerous cabinet photographs were gifts from Edna Elliot and Alex Waugh from the estate of Dr. James Randolph Miller). Series Descriptions: Portrait File: Prints and photographs of actors, actresses, playwrights, composers, opera stars, movie stars, dancers and other performing artists. The portraits are arranged by name in three groups. 1) Prints and Photographs [60% American; 40% English and others] 2) Cabinet Photographs [75% American; 25 % English and others] 3) Carte de Visite Photographs and Prints [90% American; 10% English and others] (ca. 34,500 items) Finding Aid: Card Catalog of Names And Locations. v Subject File: Clippings, pamphlets, programs, prints, and photographs arranged by name and subject. Included are many prints and photographs of scenes from plays. There are extensive files on Shakespeare and Moliere. -

Mr. D'oyly Carte's “C” Company

Mr. D’Oyly Carte’s “C” Company Patience No. 1 Company from 24 March to 5 July 1884 Repertory Company from 28 July to 6 December 1884 The Era, 5 Jan. 1884, p. 23. 24 – 29 Mar. Brighton THEATRE ROYAL . — Proprietress, Mrs. H. Nye Chart. — The closing performances of the Vokes Family last week were characterised by good houses, especially so on Friday, when they took their benefit, playing The Rough Diamond and Fun in a Fog. This week the newly organised Patience company, under Mr. D’Oyly Carte’s management, commenced the first engagement of their provincial tour. The personnel of the company has been changed in its leading parts. Miss Josephine Findlay is entrusted with the title rôle. Her vocalisation is of the best order. Mr. W. E. Shine takes the place of Mr. Thorne as Bunthorne, and fully met the expectations raised. Mr. Walter Greyling is the Grosvenor, and his previous acquaintance with the part did him good service. Mr. Byron Browne is the Colonel, Mr. Halley the Major, and Mr. R. Christian plays the Duke. Miss Elsie Cameron is Lady Jane, and sings the contralto music with remarkable finish. Miss Rosa Husk, Miss Blanche Symonds, and Miss Mina Rowley are the Ladies Angela, Saphir, and Ella; and the chorus is composed of excellent voices. The piece is mounted splendidly, and the costumes are superb. Mr. P.W. Taylor, for many years the acting- manager and secretary of the Brighton Aquarium, is the acting-manager of the company. [ The Era , 29 Mar. 1884.] 31 Mar. – 5 Apr.