City Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Year's Music

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fti E Y LAKS MV5IC 1896 juu> S-q. SV- THE YEAR'S MUSIC. PIANOS FOR HIRE Cramer FOR HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY Pianos BY All THE BEQUEST OF EVERT JANSEN WENDELL (CLASS OF 1882) OF NEW YORK Makers. 1918 THIS^BQQKJS FOR USE 1 WITHIN THE LIBRARY ONLY 207 & 209, REGENT STREET, REST, E.C. A D VERTISEMENTS. A NOVEL PROGRAMME for a BALLAD CONCERT, OR A Complete Oratorio, Opera Recital, Opera and Operetta in Costume, and Ballad Concert Party. MADAME FANNY MOODY AND MR. CHARLES MANNERS, Prima Donna Soprano and Principal Bass of Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden, London ; also of 5UI the principal ©ratorio, dJrtlustra, artii Sgmphoiu) Cxmctria of ©wat Jfvitain, Jtmmca anb Canaba, With their Full Party, comprising altogether Five Vocalists and Three Instrumentalists, Are now Booking Engagements for the Coming Season. Suggested Programme for Ballad and Opera (in Costume) Concert. Part I. could consist of Ballads, Scenas, Duets, Violin Solos, &c. Lasting for about an hour and a quarter. Part II. Opera or Operetta in Costume. To play an hour or an hour and a half. Suggested Programme for a Choral Society. Part I. A Small Oratorio work with Chorus. Part II. An Operetta in Costume; or the whole party can be engaged for a whole work (Oratorio or Opera), or Opera in Costume, or Recital. REPERTOIRE. Faust (Gounod), Philemon and Baucis {Gounod) (by arrangement with Sir Augustus Harris), Maritana (Wallace), Bohemian Girl (Balfe), and most of the usual Oratorios, &c. -

Langue Et Altérité Dans La Culture De La Renaissance

s s e e r n u t r l e u h t U CŒUR DE L ORGANISATION SOCIALE de la Grèce antique et C ’ O e c de l’institution théâtrale s’inscrivait Dionysos, « la figure de d n n l’Autre » par excellence (Louis Gernet). Le théâtre a a A s s élisabéthain, quant à lui, plaçait le festif ou l’Altérité prohibée dans e i g un lieu alternatif, de l’autre côté de la Tamise, comme pour mieux a a n e confronter la ville au-delà de ses frontières. Entre les murs du théâtre, u g R les garçons jouaient les rôles de femmes — fait unique en Europe à n n langue et altérité a l’époque — alors que le langage était lui-même « autre », un i mélange instable d’idiomes naturels et les langues vernaculaires L issues des cultures dominantes d’Europe continentale, marquant la disparition progressive de la langue de l’« Église d’Antan », le latin, dans la culture de la renaissance de plus en plus souvent perçu comme la langue de l’Autre suprême, le Pape Antéchrist. Ce volume tente de montrer la diversité topologique de l’Altérité dans la culture de la Renaissance en s’intéressant à la fois à la langue « autre » (la calomnie, l’insulte, le jargon des colporteurs, la e Language and Otherness in Renaissance Culture traduction, la prophétie), comme aux figures de l’« Autre » (le c fantôme, le bâtard, le garçon acteur travesti, l’homme des bois…) n a s s i In Ancient Greece, the institution of the theatre marked the a é n installation, at the centre of society, of Dionysus, “the figure of the t i textes réunis par e Other” par excellence (Louis Gernet). -

Press Release Fourth Round of Small Grants Announced

Email not displaying correctly? View it in your browser. PRESS RELEASE FOURTH ROUND OF SMALL GRANTS ANNOUNCED BY THE THEATRES TRUST 8am, 29 January 2014, London, UK The Theatres Trust is pleased to announce its fourth round of small capital grants to theatres across the nation. Awards are made to five community theatres for projects that will make important capital improvements, including one of the rarest surviving music halls, Hoxton Hall, and the community-owned and volunteer-run Beccles Public Hall & Theatre. Grants have been awarded to: Alnwick Playhouse: This cultural hub in Northumberland receives £5,000 towards the ‘Alnwick Playhouse & Community Arts Centre Roof Repairs’ project to enable it to carry out urgent remedial repairs and protect the fabric of the building. Beccles Public Hall & Theatre: It receives £5,000 towards an ‘Improving Access to the Stage’ project, removing part of a side wall to give better access to the stage, and remedial works to remodel the roof as part of a larger programme of renovation and improvement works. Hoxton Hall, London: This rare Grade II* listed music hall in Hackney, East London, receives £5,000 towards its ‘Conservation, Restoration and Modernisation’ project to carry out structural and strengthening works to its upper balcony which will enable it to create four new and accessible performance formats. Tara Arts: London’s first Asian-led theatre, based in Wandsworth, receives £5,000 towards the installation of a set of internal double-leaf, fire-proof acoustic doors for its new auditorium as part of the ‘Tara Theatre Renovation Project’. Yvonne Arnaud Theatre: Guildford’s Grade II listed theatre receives £5,000 towards the ‘Refurbishment and Installation of Automatic Sliding Doors’ to improve accessibility through upgrading the main entrance to the theatre and the entrance to the auditorium. -

![Theater Souvenir Programs Guide [1881-1979]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6681/theater-souvenir-programs-guide-1881-1979-256681.webp)

Theater Souvenir Programs Guide [1881-1979]

Theater Souvenir Programs Guide [1881-1979] RBC PN2037 .T54 1881 Choose which boxes you want to see, go to SearchWorks record, and page boxes electronically. BOX 1 1: An Illustrated Record by "The Sphere" of the Gilbert & Sullivan Operas 1939 (1939). Note: Operas: The Mikado; The Goldoliers; Iolanthe; Trial by Jury; The Pirates of Penzance; The Yeomen of the Guard; Patience; Princess Ida; Ruddigore; H.M.S. Pinafore; The Grand Duke; Utopia, Limited; The Sorcerer. 2: Glyndebourne Festival Opera (1960). Note: 26th Anniversary of the Glyndebourne Festival, operas: I Puritani; Falstaff; Der Rosenkavalier; Don Giovanni; La Cenerentola; Die Zauberflöte. 3: Parts I Have Played: Mr. Martin Harvey (1881-1909). Note: 30 Photographs and A Biographical Sketch. 4: Souvenir of The Christian King (Or Alfred of "Engle-Land"), by Wilson Barrett. Note: Photographs by W. & D. Downey. 5: Adelphi Theatre : Adelphi Theatre Souvenir of the 200th Performance of "Tina" (1916). 6: Comedy Theatre : Souvenir of "Sunday" (1904), by Thomas Raceward. 7: Daly's Theatre : The Lady of the Rose: Souvenir of Anniversary Perforamnce Feb. 21, 1923 (1923), by Frederick Lonsdale. Note: Musical theater. 8: Drury Lane Theatre : The Pageant of Drury Lane Theatre (1918), by Louis N. Parker. Note: In celebration of the 21 years of management by Arthur Collins. 9: Duke of York's Theatre : Souvenir of the 200th Performance of "The Admirable Crichton" (1902), by J.M. Barrie. Note: Oil paintings by Chas. A. Buchel, produced under the management of Charles Frohman. 10: Gaiety Theatre : The Orchid (1904), by James T. Tanner. Note: Managing Director, Mr. George Edwardes, musical comedy. -

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland a study © Adrienne Clare Scullion Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD to the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of Glasgow. March 1992 ProQuest Number: 13818929 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818929 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Frontispiece The Clachan, Scottish Exhibition of National History, Art and Industry, 1911. (T R Annan and Sons Ltd., Glasgow) GLASGOW UNIVERSITY library Abstract This study investigates the cultural scene in Scotland in the period from the 1880s to 1939. The project focuses on the effects in Scotland of the development of the new media of film and wireless. It addresses question as to what changes, over the first decades of the twentieth century, these two revolutionary forms of public technology effect on the established entertainment system in Scotland and on the Scottish experience of culture. The study presents a broad view of the cultural scene in Scotland over the period: discusses contemporary politics; considers established and new theatrical activity; examines the development of a film culture; and investigates the expansion of broadcast wireless and its influence on indigenous theatre. -

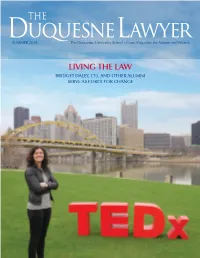

Living the Law Bridget Daley, L’13, and Other Alumni Serve As Force for Change Message from the Dean

THE SUMMER 2018 The Duquesne University School of Law Magazine for Alumni and Friends LIVING THE LAW BRIDGET DALEY, L’13, AND OTHER ALUMNI SERVE AS FORCE FOR CHANGE MESSAGE FROM THE DEAN Dean’s Message Congratulations to our newest alumni! Duquesne Law read about a new faculty/student mentorship program, which celebrated the 104th commencement on May 25 with the Class was made possible with alumni donations. You will also read of 2018 and their families, friends and colleagues. These J.D. and about alumni who are serving their communities in new ways, LL.M. graduates join approximately 7,800 Duquesne Law alumni often behind the scenes and with little fanfare, taking on pro residing throughout the world. bono cases, volunteering at nonprofit organizations, coordinating We all can be proud of what our graduates have community services and starting projects to help individuals in accomplished and the opportunities they have. Many of these need. You will discover how Duquesne Law is expanding diversity accomplishments and opportunities have been made possible and inclusion initiatives and read about new faculty roles in the because of you, our alumni. Indeed, our alumni go above and community as well as new scholarly works. Finally, you will read beyond to help ensure student success here. Colleagues in the about student achievements and the amazing work of student law often share with me that the commitment of Duquesne Law organizations here. alumni is something special! I invite you to be in touch and to join us for one of our Thank you most sincerely for all that you do! Whether you alumni events. -

CYMBELINE" in the Fllii^Slhi TI CENTURY

"CYMBELINE" IN THE fllii^SLHi TI CENTURY Bennett Jackson Submitted in partial fulfilment for the de ree of uaster of Arts in the University of Birmingham. October 1971. University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. SYNOPSIS This thesis consists of an Introduction, followed by Part I (chapters 1-2) in which nineteenth- century criticism of the play is discussed, particular attention being paid to Helen Faucit's essay on Imogen, and its relationship to her playing of the role. In Part II the stags-history of Oymbcline in London is traced from 1785 to Irving's Lyceum production of 1896. Directions from promptbooks used by G-.P. Cooke, W.C. Macready, Helen Eaucit, and Samuel ±helps are transcribed and discussed, and in the last chapter the influence of Bernard Shaw on Ellen Terry's Imogen is considered in the light of their correspondence and the actress's rehearsal copies of the play. There are three appendices: a list of performances; transcriptions of two newspaper reviews (from 1843 and 1864) and one private diary (Gordon Crosse's notes on the Lyceum Gymbeline); and discussion of one of the promptbooks prepared for Charles Kean's projected production. -

Oxford Scholarship Online

White Womanhood and Early Campaigns for Choreographic Copyright University Press Scholarship Online Oxford Scholarship Online Choreographing Copyright: Race, Gender, and Intellectual Property Rights in American Dance Anthea Kraut Print publication date: 2015 Print ISBN-13: 9780199360369 Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: November 2015 DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199360369.001.0001 White Womanhood and Early Campaigns for Choreographic Copyright Anthea Kraut DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199360369.003.0002 Abstract and Keywords This chapter recounts Loïe Fuller’s pursuit of intellectual property rights in the late nineteenth century. Focusing on the 1892 case Fuller v. Bemis, it approaches Fuller’s lawsuit as a gendered struggle to attain proprietary rights in whiteness. First situating Fuller’s practice in the context of the patriarchal economy that governed the late nineteenth-century theater, the chapter then examines the lineage of her Serpentine Dance, including the Asian Indian dance sources to which it was indebted. It also shows how the “theft” of her Serpentine Dance occasioned a crisis of subjecthood for Fuller, and how her assertion of copyright was an attempt to (re)establish herself as a property-holding subject. The chapter ends by considering the copyright bids of two dancers Page 1 of 65 PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2015. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a monograph in OSO for personal use (for details see http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/page/privacy-policy). Subscriber: New York University; date: 26 July 2016 White Womanhood and Early Campaigns for Choreographic Copyright who followed in Fuller’s wake, Ida Fuller and Ruth St. -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pick, J.M. (1980). The interaction of financial practices, critical judgement and professional ethics in London West End theatre management 1843-1899. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/7681/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] THE INTERACTION OF FINANCIAL PRACTICES, CRITICAL JUDGEMENT AND PROFESSIONAL ETHICS IN LONDON WEST END THEATRE MANAGEMENT 1843 - 1899. John Morley Pick, M. A. Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the City University, London. Research undertaken in the Centre for Arts and Related Studies (Arts Administration Studies). October 1980, 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 4 Abstract 5 One. Introduction: the Nature of Theatre Management 1843-1899 6 1: a The characteristics of managers 9 1: b Professional Ethics 11 1: c Managerial Objectives 15 1: d Sources and methodology 17 Two. -

To Center City: the Evolution of the Neighborhood of the Historicalsociety of Pennsylvania

From "Frontier"to Center City: The Evolution of the Neighborhood of the HistoricalSociety of Pennsylvania THE HISToRICAL SOcIETY OF PENNSYLVANIA found its permanent home at 13th and Locust Streets in Philadelphia nearly 120 years ago. Prior to that time it had found temporary asylum in neighborhoods to the east, most in close proximity to the homes of its members, near landmarks such as the Old State House, and often within the bosom of such venerable organizations as the American Philosophical Society and the Athenaeum of Philadelphia. As its collections grew, however, HSP sought ever larger quarters and, inevitably, moved westward.' Its last temporary home was the so-called Picture House on the grounds of the Pennsylvania Hospital in the 800 block of Spruce Street. Constructed in 1816-17 to exhibit Benjamin West's large painting, Christ Healing the Sick, the building was leased to the Society for ten years. The Society needed not only to renovate the building for its own purposes but was required by a city ordinance to modify the existing structure to permit the widening of the street. Research by Jeffrey A. Cohen concludes that the Picture House's Gothic facade was the work of Philadelphia carpenter Samuel Webb. Its pointed windows and crenellations might have seemed appropriate to the Gothic darkness of the West painting, but West himself characterized the building as a "misapplication of Gothic Architecture to a Place where the Refinement of Science is to be inculcated, and which, in my humble opinion ought to have been founded on those dear and self-evident Principles adopted by the Greeks." Though West went so far as to make plans for 'The early history of the Historical Soiety of Pennsylvania is summarized in J.Thomas Scharf and Thompson Westcott, Hisiory ofPhiladelphia; 1609-1884 (2vols., Philadelphia, 1884), 2:1219-22. -

Thomas Hardy, the Life and Work of Thomas Hardy, (Ed.) Michael Drama and the Theatre: the Dynasts' and 'The Famous Tragedy of Th

Notes Notes to the Introduction 1. Thomas Hardy, The Life and Work of Thomas Hardy, (ed.) Michael Millgate (London, Macmillan, 1984; Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1985) p. 56. Hereafter cited as Life and Work. 2. While this is the first full-length study of Hardy's interest and involvement in the theatre, it takes its place within the small but solid body of scholarship that has appeared since Marguerite Roberts first addressed two specific aspects of the subject in her books Tess in the Theatre (University of Toronto Press, 1950) and Hardy's Poetic Drama and the Theatre: The Dynasts' and 'The Famous Tragedy of the Queen of Cornwall' (New York: Pageant Press, 1965). Other significant contributions are David N. Baron, 'Harry Pouncy and the Hardy Players', Notes and Queries for Somerset and Dorset, 31 (September 1980) pp. 45-50 and his 'Hardy and the Dorchester Pouncys- Part Two', Notes and Queries for Somerset and Dorset, 31 (September 1981) pp. 129-35; Harold Orel, 'Hardy and the Theatre', in Margaret Drabble (ed.), The Genius of Thomas Hardy (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1976) pp. 94-108, and 'Hardy's Interest in the Theatre' in Harold Ore!, The Unknown Thomas Hardy (Brighton: Harvester, 1987) pp. 37--{;6; Desmond Hawkins's very helpful checklist of dramatiza tions, which forms an appendix (pp. 225-36) to his Hardy, Novelist and Poet (Newton Abbot: David & Charles, 1976); and Joan Grundy's 'Theatrical Arts', in her Hardy and the Sister Arts (London: Macmillan, 1979) pp. 70-105. Mention should also be made of Vincent Tollers's useful unpublished doctoral dissertation, 'Thomas Hardy and the Professional Theatre, with Emphasis on The Dynasts' (University of Colorado, 1968) and James Stottlar's 'Hardy vs. -

Class, Respectability and the D'oyly Carte Opera Company 1877-1909

THE UNIVERSITY OF WINCHESTER Faculty of Arts ‘Respectable Capers’ – Class, Respectability and the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company 1877-1909 Michael Stephen Goron Doctor of Philosophy June 2014 The Thesis has been completed as a requirement for a postgraduate research Degree of the University of Winchester The word count is: 98,856 (including abstract and declarations.) THE UNIVERSITY OF WINCHESTER ABSTRACT FOR THESIS ‘Respectable Capers’: Class, Respectability and the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company 1877-1909 Michael Stephen Goron This thesis will demonstrate ways in which late Victorian social and cultural attitudes influenced the development and work of the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company, and the early professional production and performance of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas. The underlying enquiry concerns the extent to which the D’Oyly Carte Opera organisation and its work relate to an ideology, or collective mentalité, maintained and advocated by the Victorian middle- classes. The thesis will argue that a need to reflect bourgeois notions of respectability, status and gender influenced the practices of a theatrical organisation whose success depended on making large-scale musical theatre palatable to ‘respectable’ Victorians. It will examine ways in which managerial regulation of employees was imposed to contribute to both a brand image and a commercial product which matched the ethical values and tastes of the target audience. The establishment of a company performance style will be shown to have evolved from behavioural practices derived from the absorption and representation of shared cultural outlooks. The working lives and professional preoccupations of authors, managers and performers will be investigated to demonstrate how the attitudes and working lives of Savoy personnel exemplified concerns typical to many West End theatre practitioners of the period, such as the drive towards social acceptability and the recognition of theatre work as a valid professional pursuit, particularly for women.