The Icon of Great

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 2018 Newsletter

Proistamenos: Fr. Douglas Papulis ST. NICHOLAS (636) 527-7843 (314) 974-4613cell MONTHLY NEWSLETTER Parish Priest: Fr. Michael Arbanas ST. NICHOLAS GREEK ORTHODOX CHURCH (314)909-6999 4967 FOREST PARK AVENUE Office (314)361-6924 ST. LOUIS, MO 63108-1495 Fax (314)361-3539 Executive Secretary: Kathy Ellis ST. NICHOLAS CHURCH FAMILY LIFE CENTER Bookkeeper: Diane Winkler 12550 S FORTY DRIVE Email: [email protected] ST. LOUIS, MO 63141 Website: www.sngoc.org January 2018 Volume 22- Number 1 The Feast of Epiphany Christ, according to Orthodox teaching, gave the rite of passage to the Church on the day He Himself was baptized. On this day, St. Gregory of Nyssa tells us, Jesus entered the filthy water of the world, and thereafter brought up and purified the world. It is this purification through Je- sus’ Baptism that we commemorate on this day. And it is God’s revelation of Himself as Trinity who makes salvation and eternal life possible, that we also observe. Epiphany’s Gospel les- son, which comes from Matthew 3:12-17, speaks to us about these events, both of which are necessary for salvation The Gospel lesson is a simple one. Shortly before Jesus’ desert experience and the com- mencement of his earthly ministry, Jesus went to the River Jordan to be Baptized by his cousin John. John, on seeing Jesus, knowing that He is without sin, sought to prevent Him from being baptized by saying, “I need to be Baptized by you, and are you coming to me” (Jn. 3:14)? But Jesus retorted by saying, “Permit it to be so now, for thus it is fitting to fulfill all righteousness.” Oh what a marvel! Jesus who was fully God and fully man, who had no need to be saved “through the washing of regeneration and renewing of the Holy Spirit,” condescended to be Baptized. -

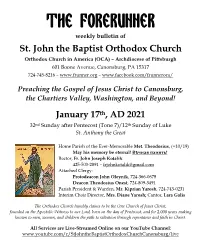

The Forerunner

The Forerunner weekly bulletin of St. John the Baptist Orthodox Church Orthodox Church in America (OCA) – Archdiocese of Pittsburgh 601 Boone Avenue, Canonsburg, PA 15317 724-745-8216 – www.frunner.org – www.facebook.com/frunneroca/ Preaching the Gospel of Jesus Christ to Canonsburg, the Chartiers Valley, Washington, and Beyond! January 17th, AD 2021 32nd Sunday after Pentecost (Tone 7)/12th Sunday of Luke St. Anthony the Great Home Parish of the Ever-Memorable Met. Theodosius, (+10/19) May his memory be eternal! Вѣчная память! Rector, Fr. John Joseph Kotalik 425-503-2891 – [email protected] Attached Clergy: Protodeacon John Oleynik, 724-366-0678 Deacon Theodosius Onest, 724-809-3491 Parish President & Warden, Mr. Kiprian Yarosh, 724-743-0231 Interim Choir Director, Mrs. Diane Yarosh; Cantor, Lara Galis The Orthodox Church humbly claims to be the One Church of Jesus Christ, founded on the Apostolic Witness to our Lord, born on the day of Pentecost, and for 2,000 years making known to men, women, and children the path to salvation through repentance and faith in Christ. All Services are Live-Streamed Online on our YouTube Channel: www.youtube.com/c/StJohntheBaptistOrthodoxChurchCanonsburg/live Upcoming Schedule January 19, Tuesday: -7:00 PM, All-OCA Online Church School for Middle and High School Students: Every Tuesday, go to https://www.oca.org/ocs and click your age group! January 21, Thursday: FR. JOHN & MAT. JANINE RETURNING January 23, Saturday: -5:15 PM, General Pannikhida -6:00 PM, Vespers & Confession January 24, Sunday (New Martyrs & Confessors of Russia; Xenia of Petersburg; Sanctity of Life Sunday): -8:45 – 9:15 AM, Confession -9:30 AM, Divine Liturgy Church Open Until Noon -6:00 PM, Moleben to St. -

Church Newsletter

Nativity of the Most Holy Theotokos Missionary Parish, Orange County, California CHURCH NEWSLETTER January – March 2010 Parish Center Location: 2148 Michelson Drive (Irvine Corporate Park), Irvine, CA 92612 Fr. Blasko Paraklis, Parish Priest, (949) 830-5480 Zika Tatalovic, Parish Board President, (714) 225-4409 Bishop of Nis Irinej elected as new Patriarch of Serbia In the early morning hours on January 22, 2010, His Eminence Metropolitan Amfilohije of Montenegro and the Littoral, locum tenens of the Patriarchate throne, served the Holy Hierarchal liturgy at the Cathedral church. His Eminence served with the concelebration of Bishops: Lukijan of Osijek Polje and Baranja, Jovan of Shumadia, Irinej of Australia and New Zealand, Vicar Bishop of Teodosije of Lipljan and Antonije of Moravica. After the Holy Liturgy Bishops gathered at the Patriarchate court. The session was preceded by consultations before the election procedure. At the Election assembly Bishop Lavrentije of Shabac presided, the oldest bishop in the ordination of the Serbian Orthodox Church. The Holy Assembly of Bishops has 44 members, and 34 bishops met the requirements to be nominated as the new Patriarch of Serbia. By the secret ballot bishops proposed candidates, out of which three bishops were on the shortlist, who received more than half of the votes of the members of the Election assembly. In the first round the candidate for Patriarch became the Metropolitan Amfilohije of Montenegro and the Littoral, in the second round the Bishop Irinej of Nis, and a third candidate was elected in the fourth round, and that was Bishop Irinej of Bachka. These three candidates have received more that a half votes during the four rounds of voting. -

TYPIKON (Arranged by Rev

TYPIKON (Arranged by Rev. Taras Chaparin) January 2018 Sunday, January 28 of the Prodigal Son Our Venerable Father Ephrem the Syrian (373). Tone 1. Matins Gospel I. Bright vestments. Tropar of the Tone of the Week; Glory/Now: Kondak of the Triod; Prokimen, Alleluia Verses and Communion Hymn of the Tone of the Week. Scripture readings for the Sunday of the Prodigal Son: Epistle: 1 Corinthians §135 [6:12-20]. Gospel: Luke §79 [15:11-32]. Monday, January 29 The Transfer of the Relics of the Great-Martyr Ignatius the God-bearer (of Antioch). Bright vestments. Weekday Service for Monday. Scripture readings for Meatfare Monday: Epistle: 1 John §71 [2:18-3-10]. Gospel: Mark §49 [11:1-11]. Tuesday, January 30 The Three Holy and Great Hierarchs: Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian, and John Chrysostom and the Holy Priest-Martyr Hippolytus (235). Bright vestments. Service for January 30. Scripture readings for the Three Holy Hierarchs: Epistle: Hebrew §334 [13:7-16]. Gospel: Matthew §11[5:14-19]. Wednesday, January 31 The Holy Wonderworkers and Unmercenaries Cyrus and John (284-305). Dark vestments. Weekday Service for Wednesday. Scripture readings for Meatfare Wednesday: Epistle: 1 John §73 [3:21-4:6]. Gospel: Mark §65 [14:43-15:1]. February 2018 Thursday, February 1 Fore-feast of the Encounter; the Holy Martyr Tryphon (249-51). Bright vestments. Tropar and Kondak of the Fore-feast. Prokimen, Alleluia Verses, and Communion Hymn of Thursday. Scripture readings for Meatfare Thursday: Epistle: 1 John §74 [4:20-5:21]. Gospel: Mark §66 [15:1-15]. -

Pastoral Visit to Georgia, August 2014

The Inauguration of the Holy Diocese of Gldani, Tbilisi, Georgia Pastoral Visit to the Holy Land of Georgia August 13-19, 2014 (Old Style) nder the protection of the Panagia Portaïtissa “the Iberian,” of St. Nina, Equal to the Apos- Utles and Enlightener of Georgia (Iberia), and of the Holy Great Martyr George, we were once again vouchsafed to visit the Holy Land of Georgia. A party of ten pilgrims from Greece, consisting of six laypeople, two nuns from the Convent of the Holy Angels, and a Subdeacon from the Monastery of Sts. Cyprian and Justina, under the spiritual leadership of Metropolitan Cyprian of Oropos and Phyle, arrived in the blessed land of Georgia on Tuesday, August 13/26, 2014. * * * Following our blessed Union (March 5, 2014 [Old Style]) with the Synod of His Beatitude, Archbishop Kallinikos, this visit was of par- ticular significance, in that the Holy Synod has designated Metropoli- tan Cyprian Locum Tenens of the newly established Diocese of Gldani, Tbilisi. We were given an extremely moving wel come, both at the Tbilisi airport and again at the Cathedral Church of the Panagia Portaïtissa in Gldani, where countless faithful, bearing Icons and chanting hymns, led by our four Priests in Georgia, enthusiastically received the Locum Tenens with expressions of profound respect and trust. The main purpose of our visit was, first, to participate in the Great Feast of the Dormition of the Theotokos—when the Cathedral in Gldani celebrates its Patronal Feast—and, second, to make contact with the cler- gy and laity now united under one Synod, so as to cultivate profound bonds of love and unity in Christ. -

JANUARY 2007 MONDAY 1 (19 Dec.) Martyr Boniface at Tarsus in Cilicia (+290), and Righteous Aglae (Aglaida) of Rome

JANUARY 2007 MONDAY 1 (19 Dec.) Martyr Boniface at Tarsus in Cilicia (+290), and Righteous Aglae (Aglaida) of Rome. Martyrs Elias, Probus, and Ares, in Cilicia (+308). Martyrs Polyeuctus at Caeasarea in Cappadocia, and Timothy the deacon. St. Boniface the Merciful, bishop of Ferentino (VI cent.). St. Gregory, archbishop of Omirits (+c. 552). St. Elias, wonderworker of the Kyiv Caves (+c. 1188). Heb. 11, 17-23, 27-31 Mk. 9, 42 - 10, 1 TUESDAY 2 (20 Dec.) Prefestive of the Nativity of Christ. Hieromartyr Ignatius the God-bearer, bishop of Antioch (+107). St. Philogonius, bishop of Antioch (+c. 323). St.Daniel, archbishop of Serbia (+1338). Venerable Ignatius, archimandrite of the Kyiv Caves (+1435). Heb. 4, 14 – 5, 10 Mt. 5, 14-19 WEDNESDAY 3 (21 Dec.) Virgin-martyr Juliana and with her 500 men and 130 women in Nicomedia (+304). Martyr Themistocles of Myra and Lycia (+251). Repose of St. Peter, metropolitan of Kyiv and all- Rus’-Ukraine (1326). Heb. 7, 26 – 8, 2 Lk. 6, 17-23 THURSDAY 4 (22 Dec.) Great-martyr Anastasia, and her teacher Chrysogonus, and with them martyrs Theodota, Evodias, Eutychianus, and others who suffered under Diocletian (+c. 304). Gal. 3, 23-29 Lk. 7, 36-50 FRIDAY 5 (23 Dec.) Holy ten martyrs of Crete: Theodulus, Euporus, Gelasius, Eunychius, Zoticus, Pompeius, Agathopusus, Basilidus and Evarestes (III cent.).St. Niphon, bishop of Cyprus (IV cent.). St. Paul, bishop of Neo-Caesaraea (IV cent.). 1 January 2007 The Royal Hours: First Hour: Micah 5, 2-4 Heb. 1, 1-12 Mt. 1, 18-25 Third Hour: Baruch 3, 36 – 4, 4 Gal. -

Saints and Icons Vrame, the Educating Icon

"Thus the icon is also a theology, a theology in color, expressing the experience of God with lines and paints rather than with discursive language. The goal of the icon and that of written theology are the same – to lead others to the mystical experience of God. The icon artistically depicts the experience so that others may approach the mystery and be invited to share in it." - Anton Saints and Icons Vrame, The Educating Icon WEEK 2 OPENING PRAYERS: Before and after each lesson, please say a short prayer in In the name of the Father, of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen front of an icon according to your family’s prayer rule or Glory to thee, our God, glory to thee! Prayers the following, taken from the red St. Tikhon’s Prayer Book: Prayer to Holy Spirit O heavenly King, the Comforter, the Spirit of truth, who art everywhere present and fillest all things, Treasury of blessings, and Giver of life: come and abide in us, and cleanse us from every impurity, and save our souls, O Good One. CLOSING PRAYERS: “Rejoice, O Virgin Theotokos, Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with Trisagion Prayer thee. Blessed art thou among women, and blessed is the fruit of Holy God, Holy Mighty, Holy Immortal: have mercy on us. Holy God, Holy Mighty, Holy thy womb: for thou hast borne the Savior of our souls. Immortal: have mercy on us. Holy God, Holy Mighty, Holy Immortal: have mercy on us. Pray to God for me, O holy [name of your patron saint], pleasing Glory to the Father and to the Son and to the Holy Spirit, now and ever and unto ages of to God, for with fervor I run to thee, swift helper and intercessor ages. -

The 30Th Day of January Synaxis of the Three Hierarchs: St. Basil the Great, St. Gregory the Theologian, and St John Chrysostom, Archbishop of Constantinople

The 30th Day of January Synaxis of the Three Hierarchs: St. Basil the Great, St. Gregory the Theologian, and St John Chrysostom, Archbishop of Constantinople. Also, Hieromartyr Hippolytus, Pope of Rome and those with him all beheaded at Ostia: the Martyrs Censorinus, Sabinus, Ares, the virgin Chryse, and with her Felix, Maximus, Herculianus, Venerius, Styracius, Menas, Commodus, Hermes, Maurus, Eusebius, Rusticus, Monagrius, Amandinus, Olympius, Cyprus, Theodore the Tribune, Maximus the Presbyter, Archelaus the Deacon, and Cyriacus the Bishop. Their service is sung at Compline. Small Evening Service 4 stikhera, in Tone 4: To the melody, “As one valiant among the martyrs....” Thou hast ascended, O Basil, / To the heights of the love of Christ / There to behold the ineffable and divine mysteries / Which thou didst reveal and explain to the people / As a wise preacher of piety, O venerable one, / Therefore pray that those who faithfully follow thy teachings, /// Be delivered from corruption and sorrow. Thou didst unravel the knots of heresy, O Gregory, / With the wisdom of thy words and teachings / And didst unite in one mind those of the Orthodox faith / To rightly glorify Christ, O ven’rable one, / Therefore pray to Him, that those who faithfully follow thy teachings, /// Be delivered from corruption and sorrow. Christ hath established thee, O venerable father, / As an unshakable foundation of His Church, / To keep her safe from the assaults of the enemy, / O golden mouth of the Word of God, / And to pray for the deliverance from soul-destroying passions /// Those thirsting for thy words and the depths of thy wisdom. -

Old and New John Chrysostom 15 November 2015 Peter Sarris

Saints – Old and New John Chrysostom 15 November 2015 Peter Sarris Luke 16: 19–end extract from John Chrysostom’s sixth sermon on Lazarus and the rich man Professionally I am an historian, primarily of the Roman, Medieval and Byzantine worlds. Within that very broad area, my work has focused on the social and economic development of the Roman and Byzantine world from the age of Constantine the Great onwards, and the historical background to the violent expansion of Islam in the seventh century. Throughout my work, I have attempted to capture the voices and life experiences of the urban poor, the peasantry, and the artisans, whose taxes helped to support the Roman and Byzantine state, and whose labours fuelled the lifestyle of members of the Roman and Byzantine aristocracy, the haughty voices of whom dominate the pages of the literary sources on which historians typically rely. These historical interests chime with my more contemporary ones, as I have long been a socialist activist, and am currently a city councillor in Cambridge, with special responsibility for homelessness and refugees. And in my address this evening, I plan to draw upon each of these strands of history and politics. St John Chrysostom, whose vivid denunciations of the wealthy you have just heard in the second reading, was, alongside St Basil of Caesarea and St Gregory Nazianzus, one of the Three Holy Hierarchs – or three ‘doctors’ or ‘teachers’ of the Church, as they are often described in the Western tradition – whose theological interventions in the fourth and fifth centuries were fundamental to the formation of Christian Orthodoxy as we understand it today. -

Saint Basil the Great

Saint Basil the Great St. Basil of Caesarea, his brother St. Gregory of Nyssa and their friend St Gregory of Nazianzius are known as the Cappadocian Fathers. They were Bishops and had done much to defend the faith of the Church by vehemently refuting the arguments of the heretics. They were saintly fathers. They oppose to Actius, Eunomius and others who rejected the Godhead and eternity of the Holy Spirit. They explained the faith of the Church in such a way as to make it possible for the human mind with its limitation to grasp the principle of the Trinity and the mystery behind the incarnation of our Lord Jesus Christ. Basil of Caesarea also known as Saint Basil the Great was the Greek bishop of Caesarea in Cappadocia, of Asia Minor. He was a very influential theologian who opposed the heresies of the early church and fought against both Arianism and the followers of Apollinaris of Laodicea. He was the strongest supporter of Nicene Creed. He had very good political connections and at the same time above all, deep theological knowledge. Saint Paul of Thebes, St. Antony, St. Pakomios and St. Makarios were the leaders of the Egyptian church tradition. St. Ephrem was the leader of the Syrian church and St. Ephiphanios was the leader of the Palastiniean church tradition. But St, Basil was the first ascetic leader of the Eastern Church tradition. Basil was born into the wealthy family of Basil the Elder and Emilia of Caesarea in Cappadocia around A. D 330. Basil the Elder was known as a scholar and eminent writer throughout Cappadocia. -

The Life of Mark the Evangelist

The Life of Mark the Evangelist April 25, 2021 Revision C Gospel: Mark 6:7-13 Epistle: 1 Peter 5:6-14 Many people have confused the Evangelist Mark with another member of the Seventy, John surnamed Mark (Acts 12:12). In addition, there was a third member of the original Seventy Apostles named Mark, who was the cousin of Barnabas (Colossians 4:10). They are three different individuals who came from different locales and who had much different roles in the Early Church. Modern accounts of these three individuals are often blended together. The Evangelist Mark was originally an idolater1 from Cyrene of Pentapolis, which is near Libya. He came to the Faith of Christ through the Apostle Peter. John Mark, on the other hand, in addition to being one of the original Seventy Apostles, was born at Jerusalem2, and the house of his mother Mary (Acts 12:12) adjoined the Garden of Gethsemane. John Mark was later Bishop of Byblos in Phoenicia just north of Beirut on the Mediterranean coast. Mark, the cousin of Barnabas, was3 also one of the original Seventy Apostles and was later the Bishop of Apollonia in Samaria, just north of Joppa on the Mediterranean coast. Since Barnabas was native to Cyprus (Acts 4:36), Mark, his cousin, probably was also native to Cyprus. After Pentecost, the Evangelist Mark accompanied the Apostle Peter (1 Peter 5:13), much as the Evangelist Luke accompanied the Apostle Paul. John Mark, on the other hand, accompanied the Apostles Paul and Barnabas on their First Missionary Journey (Acts 13:5, 13), and later worked with Barnabas on Cyprus (Acts 15:39). -

THE VIEW of the HOLY THREE HIERARCHS on CULTURE and EDUCATION † IRINEU Archbishop of Alba Iulia 1. Familiarised with the Mora

THE VIEW OF THE HOLY THREE HIERARCHS ON CULTURE AND EDUCATION † IRINEU Archbishop of Alba Iulia Abstract: The present study presents the interaction of the Three Holy Hierarchs: Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian and John Chrysostom, spiritual patrons of theological education, with the values of the secular culture of their time, marked by the expression of antique Hellenism. Interweaving genius and holiness, the Great Hierarchs of the world in the golden age of Christian Church acquired wisely all that was good in their culture, thus becoming outstanding intellectuals and perfect men. Accomodating harmoniously Christian teachings to ancient philosophy, which actually played the role of “an educator and guide towards Christ”, they can be referred to in different ways: Saint Basil - a teacher of the divine and human wisdom, Saint Gregory – an admirer of Christian and secular knowledge, and Saint John – “the most Hellenic of all Christians”. According to the original perspective of the Three Holy Hierarchs on the relation between ecclesia and universitas, we understand that the educational purpose consists of an optimal integration of man in the existing order, in society and in history. Assuming the educational model of the Three Teachers certainly leads to acquiring an inner balance and to living a life of holiness. Keywords: education, morality, culture, youth 1. Familiarised with the moral values of ancient philosophy The Three Holy Hierarchs, Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian and John Chrysostom have been established by the Orthodox Church as spiritual patrons of theological education, as they inspire and impel us to pay attention to Christian values, and ,with discernment, equally to the values in secular culture.