Reinterpreting Prehistory of Central America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nombre Del Comercio Provincia Distrito Dirección Horario

Nombre del Provincia Distrito Dirección Horario comercio Almacén Agrícola Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Cruce Del L-S 7:00am a 6:00 pm Aguas Claras Higuerón Camino A Rio Negro Comercial El Globo Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, contiguo L - S de 8:00 a.m. a 8:00 al Banco Nacional p.m. Librería Fox Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, frente al L - D de 7:00 a.m. a 8:00 Liceo Aguas Claras p.m. Librería Valverde Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, 500 norte L-D de 7:00 am-8:30 pm de la Escuela Porfirio Ruiz Navarro Minisúper Asecabri Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Las Brisas L - S de 7:00 a.m. a 6:00 400mts este del templo católico p.m. Minisúper Los Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, Cuatro L-D de 6 am-8 pm Amigos Bocas diagonal a la Escuela Puro Verde Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Porvenir L - D de 7:00 a.m. a 8:00 Supermercado 100mts sur del liceo rural El Porvenir p.m. (Upala) Súper Coco Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, 300 mts L - S de 7:00 a.m. a 7:00 norte del Bar Atlántico p.m. MINISUPER RIO Alajuela AGUAS ALAJUELA, UPALA , AGUAS CLARAS, L-S DE 7:00AM A 5:00 PM NIÑO CLARAS CUATRO BOCAS 200M ESTE EL LICEO Abastecedor El Alajuela Aguas Zarcas Alajuela, Aguas Zarcas, 25mts norte del L - D de 8:00 a.m. -

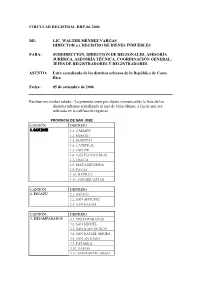

Circular Registral Drp-06-2006

CIRCULAR REGISTRAL DRP-06-2006 DE: LIC. WALTER MÉNDEZ VARGAS DIRECTOR a.i. REGISTRO DE BIENES INMUEBLES PARA: SUBDIRECCIÓN, DIRECCIÓN DE REGIONALES, ASESORÍA JURÍDICA, ASEOSRÍA TÉCNICA, COORDINACIÓN GENERAL, JEFES DE REGISTRADORES Y REGISTRADORES. ASUNTO: Lista actualizada de los distritos urbanos de la República de Costa Rica Fecha: 05 de setiembre de 2006 Reciban mi cordial saludo. La presente tiene por objeto comunicarles la lista de los distritos urbanos actualizada al mes de Julio último, a fin de que sea utilizada en la califiación registral. PROVINCIA DE SAN JOSE CANTÓN DISTRITO 1. SAN JOSE 1.1. CARMEN 1.2. MERCED 1.3. HOSPITAL 1.4. CATEDRAL 1.5. ZAPOTE 1.6. SAN FCO DOS RIOS 1.7. URUCA 1.8. MATA REDONDA 1.9. PAVAS 1.10. HATILLO 1.11. SAN SEBASTIAN CANTÓN DISTRITO 2. ESCAZU 2.1. ESCAZU 2.2. SAN ANTONIO 2.3. SAN RAFAEL CANTÓN DISTRITO 3. DESAMPARADOS 3.1. DESAMPARADOS 3.2. SAN MIGUEL 3.3. SAN JUAN DE DIOS 3.4. SAN RAFAEL ARRIBA 3.5. SAN ANTONIO 3.7. PATARRA 3.10. DAMAS 3.11. SAN RAFAEL ABAJO 3.12. GRAVILIAS CANTÓN DISTRITO 4. PURISCAL 4.1. SANTIAGO CANTÓN DISTRITO 5. TARRAZU 5.1. SAN MARCOS CANTÓN DISTRITO 6. ASERRI 6.1. ASERRI 6.2. TARBACA (PRAGA) 6.3. VUELTA JORCO 6.4. SAN GABRIEL 6.5.LEGUA 6.6. MONTERREY CANTÓN DISTRITO 7. MORA 7.1 COLON CANTÓN DISTRITO 8. GOICOECHEA 8.1.GUADALUPE 8.2. SAN FRANCISCO 8.3. CALLE BLANCOS 8.4. MATA PLATANO 8.5. IPIS 8.6. RANCHO REDONDO CANTÓN DISTRITO 9. -

Sucursales Correos De Costa Rica

SUCURSALES CORREOS DE COSTA RICA Oficina Código Dirección Sector 27 de Abril 5153 Costado sur de la Plaza. Guanacaste, Santa Cruz, Veintisiete de Abril. 50303 Resto del País Acosta 1500 Costado Este de la Iglesia Católica, contiguo a Guardia de Asistencia Rural, San GAM Ignacio, Acosta, San José 11201 Central 1000 Frente Club Unión. San José, San Jose, Merced. 10102 GAM Aguas Zarcas 4433 De la Iglesia Católica, 100 metros este y 25 metros sur. Alajuela, San Carlos, Resto del País Aguas Zarcas. 21004 Alajuela 4050 Calle 5 Avenida 1. Alajuela, Alajuela. 20101 GAM Alajuelita 1400 De la iglesia Católica 25 metros al sur San José, Alajuelita, Alajuelita. 11001 GAM Asamblea 1013 Edificio Central Asamblea Legislativa San José, San Jose, Carmen. 10101 GAM Legislativa Aserrí 1450 Del Liceo de Aserrí, 50 metros al norte. San José, Aserrí, Aserrí. 10601 GAM Atenas 4013 De la esquina sureste de el Mercado, 30 metros este. Alajuela, Atenas, Atenas. Resto del País 20501 Bagaces 5750 Contiguo a la Guardia de Asistencia Rural. Guanacaste, Bagaces, Bagaces. Resto del País 50401 Barranca 5450 Frente a Bodegas de Incoop. Puntarenas, Puntarenas, Barranca. 60108 Resto del País Barrio México 1005 De la plaza de deportes 50 metros norte y 25 metros este, San José, San José, GAM Merced. 10102 Barrio San José de 4030 De la iglesia Católica, 200 metros oeste. Alajuela, Alajuela , San José. 20102 GAM Alajuela Barva de Heredia 3011 Calle 4, Avenida 6. Heredia, Barva, Barva. 40201 GAM Bataán 7251 Frente a la parada de Buses. Limón, Matina, Batan. 70502 Resto del País Boca de Arenal 4407 De la Iglesia Católica, 200 metros sur. -

1 a Guide to Working on the Lomas Barbudal Monkey

A GUIDE TO WORKING ON THE LOMAS BARBUDAL MONKEY PROJECT, FOR PROSPECTIVE FIELD ASSISTANTS – last updated Sept 18, 2016 I. Historical Background: In 1990, Susan Perry and Joe Manson arrived in Costa Rica with the idea of establishing a long-term field site for the study of capuchins and howler monkeys. We chose Lomas Barbudal Biological Reserve because a study done by Colin Chapman et al. had revealed that both species were abundant there. We rapidly discovered that the monkeys regularly ranged outside the park into many private farms and ranches (e.g. Hacienda Pelon de la Bajura and Hacienda Brin D’Amor, as well as many small farms in the community of San Ramon de Bagaces), and fortunately these landowners also gave us permission to conduct research there. Joe began working with howlers, and Susan began her dissertation work on capuchin monkeys. Susan habituated a single group of monkeys (Abby's group), which was the focus of her dissertation work in 1991-3. Howlers turned out to be excruciatingly boring, so Joe opted to help Susan instead of continue with that work and did his own research in subsequent field seasons. Julie Gros-Louis joined us as Susan's assistant beginning in 1991 and eventually came back to do her own dissertation work in 1996, when she began habituation of the second study group (Rambo's group). Beginning in 2001, observations of the monkeys have continued without a break. Since 2001, Susan has taken the lead role in running the site, while a manager (or two-person managerial team) is in charge of day-to- day project supervision, particularly when Susan is in the U.S. -

Centros Educativos Declarados Dentro De La Zona De Alerta Roja

CENTROS EDUCATIVOS DECLARADOS DENTRO DE LA ZONA DE ALERTA ROJA Código presupue CIRC stario NOMBRE DE LA INSTITUCIÓN PROVINCIA CANTÓN DISTRITO Dirección Regional ESCOL Nivel 4232 C.T.P. UPALA ALAJUELA UPALA UPALA ZONA NORTE-NORTE 01 Colegio 5670 LICEO COLONIA PUNTARENAS ALAJUELA UPALA UPALA ZONA NORTE-NORTE 08 Colegio SECCION NOCTURNA C.T.P. 4232 UPALA ALAJUELA UPALA UPALA ZONA NORTE-NORTE 01 Colegio TELESECUNDARIA LOS JAZMINES 5596 B ALAJUELA UPALA UPALA ZONA NORTE-NORTE 08 Colegio 3835 COLONIA PUNTARENAS ALAJUELA UPALA UPALA ZONA NORTE-NORTE 08 Escuela 3872 DR. RICARDO MORENO CAÑAS ALAJUELA UPALA UPALA ZONA NORTE-NORTE 03 Escuela 3875 EL CARMEN # 2 ALAJUELA UPALA UPALA ZONA NORTE-NORTE 01 Escuela 3852 EL FOSFORO ALAJUELA UPALA UPALA ZONA NORTE-NORTE 01 Escuela 3844 EL HIGUERON ALAJUELA UPALA UPALA ZONA NORTE-NORTE 04 Escuela 3832 EL PROGRESO ALAJUELA UPALA UPALA ZONA NORTE-NORTE 04 Escuela 3878 EL RECREO ALAJUELA UPALA UPALA ZONA NORTE-NORTE 08 Escuela 5648 LA PALMERA ALAJUELA UPALA UPALA ZONA NORTE-NORTE 01 Escuela 3917 LLANO AZUL ALAJUELA UPALA UPALA ZONA NORTE-NORTE 04 Escuela 3837 LOS INGENIEROS ALAJUELA UPALA UPALA ZONA NORTE-NORTE 01 Escuela 3795 LOS JAZMINES ALAJUELA UPALA UPALA ZONA NORTE-NORTE 08 Escuela 5647 MIRAVALLES ALAJUELA UPALA UPALA ZONA NORTE-NORTE 08 Escuela 3839 NAHUATL ALAJUELA UPALA UPALA ZONA NORTE-NORTE 01 Escuela 3798 PORFIRIO CAMPOS MUÑOZ ALAJUELA UPALA UPALA ZONA NORTE-NORTE 08 Escuela 3918 SAN FERNANDO ALAJUELA UPALA UPALA ZONA NORTE-NORTE 01 Escuela 3919 SAN LUIS ALAJUELA UPALA UPALA ZONA NORTE-NORTE 08 Escuela -

Provincia Nombre Provincia Cantón Nombre Cantón Distrito Nombre

Provincia Nombre Provincia Cantón Nombre Cantón Distrito Nombre Distrito Barrio Nombre Barrio 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 1 Amón 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 2 Aranjuez 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 3 California (parte) 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 4 Carmen 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 5 Empalme 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 6 Escalante 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 7 Otoya. 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 1 Bajos de la Unión 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 2 Claret 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 3 Cocacola 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 4 Iglesias Flores 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 5 Mantica 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 6 México 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 7 Paso de la Vaca 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 8 Pitahaya. 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 1 Almendares 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 2 Ángeles 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 3 Bolívar 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 4 Carit 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 5 Colón (parte) 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 6 Corazón de Jesús 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 7 Cristo Rey 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 8 Cuba 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 9 Dolorosa (parte) 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 10 Merced 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 11 Pacífico (parte) 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 12 Pinos 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 13 Salubridad 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 14 San Bosco 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 15 San Francisco 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 16 Santa Lucía 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 17 Silos. -

Intervención Del Ministerio De Salud Contaminación Por Arsénico En Comunidades De Cañas, Bagaces, Los Chiles Y Aguas Zarcas

MINISTERIO DE SALUD DIRECCION DE PROTECCION AL AMBIENTE HUMANO Unidad Administración de Servicios de Salud en Ambiente Humano Teléfonos: 221-6058 / Fax: 2222-1420 Correo electrónico: [email protected] INTERVENCIÓN DEL MINISTERIO DE SALUD CONTAMINACIÓN POR ARSÉNICO EN COMUNIDADES DE CAÑAS, BAGACES, LOS CHILES Y AGUAS ZARCAS 1. Contexto Comisión Agua Segura Siendo notificadas las instituciones recurridas en el VOTO N° 2013007598 indicando las acciones de las instituciones para enfrentar y solucionar la situación, el Despacho de la Ministra de Salud conformó una Comisión interinstitucional e intersectorial con el objetivo de coordinar las acciones y proponer soluciones a la comunidades afectadas en los cantones de Cañas, Bagaces, Los Chiles, San Carlos (Aguas Zarcas). Iniciativa del Despacho de la Ministra de Salud que pretende abordar la problemática emergente de contaminación por elevadas concentraciones de Arsénico en dichas comunidades. El Plan de Agua Segura, entre otros objetivos, crea la Comisión de Agua Segura que corresponde a una convocatoria de actores clave de instituciones y sociedad civil para facilitar el dialogo deliberativo sustentado en bases racionales para llegar a soluciones beneficiando la salud pública de los pobladores afectados por el problema de marras. La creación de la Comisión de Agua Segura está basada en el compromiso de eficiencia, equidad y sostenibilidad con enfoque de derecho humano para el acceso a agua potable. 2. Miembros de la Comisión: a) Ministerio de Salud que conduce a través de la Señora Ministra, Dirección de Protección al Ambiente Humano, Dirección de Vigilancia de la Salud y los Directores de las Áreas Rectoras de Salud de Bagaces, Cañas y Aguas Zarcas. -

Codigos Geograficos

División del Territorio de Costa Rica Por: Provincia, Cantón y Distrito Según: Código 2007 Código Provincia, Cantón y Distrito COSTA RICA 1 PROVINCIA SAN JOSE 101 CANTON SAN JOSE 10101 Carmen 10102 Merced 10103 Hospital 10104 Catedral 10105 Zapote 10106 San Francisco de Dos Ríos 10107 Uruca 10108 Mata Redonda 10109 Pavas 10110 Hatillo 10111 San Sebastián 102 CANTON ESCAZU 10201 Escazú 10202 San Antonio 10203 San Rafael 103 CANTON DESAMPARADOS 10301 Desamparados 10302 San Miguel 10303 San Juan de Dios 10304 San Rafael Arriba 10305 San Antonio 10306 Frailes 10307 Patarrá 10308 San Cristóbal 10309 Rosario 10310 Damas 10311 San Rafael Abajo 10312 Gravilias 10313 Los Guido 104 CANTON PURISCAL 10401 Santiago 10402 Mercedes Sur 10403 Barbacoas 10404 Grifo Alto 10405 San Rafael 10406 Candelaria 10407 Desamparaditos 10408 San Antonio 10409 Chires 105 CANTON TARRAZU 10501 San Marcos 10502 San Lorenzo 10503 San Carlos 106 CANTON ASERRI 10601 Aserrí 10602 Tarbaca o Praga 10603 Vuelta de Jorco 10604 San Gabriel 10605 La Legua 10606 Monterrey 10607 Salitrillos 107 CANTON MORA 10701 Colón 10702 Guayabo 10703 Tabarcia 10704 Piedras Negras 10705 Picagres 108 CANTON GOICOECHEA 10801 Guadalupe 10802 San Francisco 10803 Calle Blancos 10804 Mata de Plátano 10805 Ipís 10806 Rancho Redondo 10807 Purral 109 CANTON SANTA ANA 10901 Santa Ana 10902 Salitral 10903 Pozos o Concepción 10904 Uruca o San Joaquín 10905 Piedades 10906 Brasil 110 CANTON ALAJUELITA 11001 Alajuelita 11002 San Josecito 11003 San Antonio 11004 Concepción 11005 San Felipe 111 CANTON CORONADO -

“Bee-Flower-People Relationships, Field Biologists, and Conservation in Northwest Urban Costa Rica and Beyond.”

Zoosymposia 12: 018–028 (2018) ISSN 1178-9905 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zs/ ZOOSYMPOSIA Copyright © 2018 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1178-9913 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zoosymposia.12.1.4 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:BE014C6F-4641-487D-9B78-799E6CA5037F “Bee-Flower-People Relationships, Field Biologists, and Conservation in Northwest Urban Costa Rica and Beyond.” G. W. FRANKIE1, R. E. COVILLE2, J. C. PAWELE3, C. C. JADALLAH1, S. B. VINSON4 & L. E. S. MARTINEZ5 1University of California, Berkeley, CA, 94720 2Professional Entomologist/Photographer, El Cerrito, CA, 94804 3Professional Landscape Designer and Bee Taxonomist, Richmond, CA, 94805 4Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, 77843 5Private Naturalist/Bee Ecologist, Bagaces, Guanacaste, Costa Rica Abstract The forests of Costa Rica are rich in a wide variety of pollinator types and a very diverse flora that supports them. Our research group from the University of California, Berkeley and Texas A & M University, College Station has been researching the ecology of one pollinator group, the bees, in the northwest Guanacaste dry forest region since 1969. Much natural forest existed in this area when we first began the work. But, many land use changes have occurred over the years to present day to the point that it is difficult to find tracts of undisturbed forest suitable for field research, especially those not affected by wildfires, which are now common. Further, urban areas in the region continue to grow with increasing numbers of people populating the region. In this paper we provide an overview of our past bee-flower work for a historical perspective, and then weave in people that have now become an obvious ecological component of current bee-flower relationships. -

Regiones Y Cantones De Costa Rica

DIRECCIÓN DE GESTIÓN MUNICIPAL SECCIÓN DE INVESTIGACIÓN Y DESARROLLO REGIONES Y CANTONES DE COSTA RICA SERIE CANTONES DE COSTA RICA : N° 2 2003 DIRECCIÓN DE GESTIÓN MUNICIPAL SECCIÓN DE INVESTIGACIÓN Y DESARROLLO REGIONES Y CANTONES DE COSTA RICA Elaborado por: Ronulfo Alvarado Salas SERIE CANTONES DE COSTA RICA : N° 2 2003 CONTENIDO Página N° PRESENTACIÓN 1 1 El Proceso de Regionalización en Costa Rica 3 2 Sobre el concepto de región 7 3 Información básica sobre las regiones en Costa Rica 10 ANEXOS N°1 Mapa sobre las regiones en Costa Rica 51 N°2 Población y territorio según región 52 N°3 Población y territorio según provincia 53 BIBLIOGRAFÍA 53 PRESENTACIÓN En el primer documento de esta serie sobre cantones de Costa Rica, se analizaron algunos de los inconvenientes que presenta la actual división territorial administrativa para efectos, entre otros cosas, de planificar y coordinar los programas de desarrollo que llevan a cabo las diversas instituciones del país. Es corriente que sobre un mismo territorio se proyecten diversas instituciones con grados diferentes de competencias y especialización, sin que hasta el momento se haya podido obtener una acción armónica y eficaz entre ellas. En algunas provincias hasta 44 instituciones públicas (ministerios, entidades descentralizadas, municipalidades) realizan sus labores sin una coordinación estratégica y operativa que garantice el mejor uso de los cuantiosos recursos que están implicados. La regionalización se planteó como una forma de mejorar los procesos de planificación y coordinación interinstitucional, no solo para garantizar un mejor uso de los recursos públicos sino también para procurar un desarrollo más equitativo y armonioso entre las diferentes regiones del país, evitando en lo posible las brechas o desequilibrios regionales que una serie de estadísticas han venido a poner hoy en día más de manifiesto. -

2010 Death Register

Costa Rica National Institute of Statistics and Censuses Department of Continuous Statistics Demographic Statistics Unit 2010 Death Register Study Documentation July 28, 2015 Metadata Production Metadata Producer(s) Olga Martha Araya Umaña (OMAU), INEC, Demographic Statistics Unit Coordinator Production Date July 28, 2012 Version Identification CRI-INEC-DEF 2010 Table of Contents Overview............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Scope & Coverage.............................................................................................................................................. 4 Producers & Sponsors.........................................................................................................................................5 Data Collection....................................................................................................................................................5 Data Processing & Appraisal..............................................................................................................................6 Accessibility........................................................................................................................................................ 7 Rights & Disclaimer........................................................................................................................................... 8 Files Description................................................................................................................................................ -

Republic of Costa Rica X National Population Census and Vi Housing

REPUBLIC OF COSTA RICA X NATIONAL POPULATION CENSUS AND VI HOUSING CENSUS SECTION I: LOCATION Registration Area Smallest Statistical Unit Dwelling Household This mark applies only If this form is a CONTINUATION of after the second form the same HOUSEHOLD, check here: in households with more than 6 people. Address District FILLING INSTRUCTIONS RIGTH WRONG Mark well Do not mark well SECTION II: CHARACTERISTICS OF THE DWELLING 1. Observe, probe and check the type of dwelling 4. The exterior walls are mainly . INDIVIDUAL . cinder block or brick? . 1 Independent house . 1 . concrete base and wooden top or Fibrolit? . 2 Independent house in condominium . 2 . wood? . 3 Apartment building . 3 . prefabricated or tiles? . 4 Condominium apartment building . 4 . Fibrolit, Ricalit? (asbestos cement sheet .) . 5 Traditional Indigenous Dwelling (palenque or ranch) 5 . natural fibers? (bamboo, cane, chonta) . 6 Room in shared house or building old (“cuartería”) 6 . waste material? . 7 Hovel or shack (“tugurio”) . 7 Other (zinc, adobe) . 8 Other (store, mobile home, boat, truck) . 8 5. The roof is mainly . COLLECTIVE Worker‘s house . 9 . zinc? . 1 . Fibrolit, Ricalit or cement? (fibrocement) . 2 Children’s shelter . 10 Skip to Nursing homes . 11 SECTION . natural material? (palm, straw or other suita) . 3 III, ques. 3 . waste material? . Jail . 12 4 Other (clay tile, etc) . Other (guest house, “pensión”, convent) . 13 5 Skip to 6. Does the dwelling have interior ceiling paneling? HOMELESS . 14 SECTION IV Yes . 1 No . 2 2. Inquire and check if the dwelling is occupied or unoccupied 7. The floor is mainly . OCCUPIED ... ceramic tile, linoleum flooring, terrazzo tile? .