A Guide to Working on the Lomas Barbudal Monkey Project, for Prospective Field Assistants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Endangerment and Conservation of Wildlife in Costa Rica

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Toor Cummings Center for International Studies CISLA Senior Integrative Projects and the Liberal Arts (CISLA) 2020 The Endangerment and Conservation of Wildlife in Costa Rica Dana Rodwin Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/sip Recommended Citation Rodwin, Dana, "The Endangerment and Conservation of Wildlife in Costa Rica" (2020). CISLA Senior Integrative Projects. 16. https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/sip/16 This Honors Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Toor Cummings Center for International Studies and the Liberal Arts (CISLA) at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in CISLA Senior Integrative Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. The Degradation of Forest Ecosystems in Costa Rica and the Implementation of Key Conservation Strategies Dana Rodwin Connecticut College* *Completed through the Environmental Studies Department 1 Introduction Biodiversity is defined as the “variability among living organisms… [including] diversity within species, between species, and of ecosystems” (CBD 1992). Many of the world’s most biodiverse ecosystems are found in the tropics (Brown 2014a). The country of Costa Rica, which is nestled within the tropics of Central America, is no exception. Costa Rica is home to approximately 500,000 different species, which include mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish, invertebrates, and plants. Though Costa Rica’s land area accounts for only 0.03 percent of the earth’s surface, its species account for almost 6% of the world’s biodiversity (Embajada de Costa Rica), demonstrating the high density of biodiversity in this small country. -

The Birds of Hacienda Palo Verde, Guanacaste, Costa Rica

The Birds of Hacienda Palo Verde, Guanacaste, Costa Rica PAUL SLUD SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO ZOOLOGY • NUMBER 292 SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoo/ogy Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world cf science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the world. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given substantive review. Press requirements for manuscript and art preparation are outlined on the inside back cover. -

Nombre Del Comercio Provincia Distrito Dirección Horario

Nombre del Provincia Distrito Dirección Horario comercio Almacén Agrícola Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Cruce Del L-S 7:00am a 6:00 pm Aguas Claras Higuerón Camino A Rio Negro Comercial El Globo Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, contiguo L - S de 8:00 a.m. a 8:00 al Banco Nacional p.m. Librería Fox Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, frente al L - D de 7:00 a.m. a 8:00 Liceo Aguas Claras p.m. Librería Valverde Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, 500 norte L-D de 7:00 am-8:30 pm de la Escuela Porfirio Ruiz Navarro Minisúper Asecabri Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Las Brisas L - S de 7:00 a.m. a 6:00 400mts este del templo católico p.m. Minisúper Los Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, Cuatro L-D de 6 am-8 pm Amigos Bocas diagonal a la Escuela Puro Verde Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Porvenir L - D de 7:00 a.m. a 8:00 Supermercado 100mts sur del liceo rural El Porvenir p.m. (Upala) Súper Coco Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, 300 mts L - S de 7:00 a.m. a 7:00 norte del Bar Atlántico p.m. MINISUPER RIO Alajuela AGUAS ALAJUELA, UPALA , AGUAS CLARAS, L-S DE 7:00AM A 5:00 PM NIÑO CLARAS CUATRO BOCAS 200M ESTE EL LICEO Abastecedor El Alajuela Aguas Zarcas Alajuela, Aguas Zarcas, 25mts norte del L - D de 8:00 a.m. -

Emergency Appeal Final Report Costa Rica and Panama: Population Movement

P a g e | 1 Emergency Appeal Final Report Costa Rica and Panama: Population Movement Emergency Appeal Final Report Emergency appeal no. n° MDRCR014 Date of issue: 31 December 2017 GLIDE No. OT-2015000157-CRI Date of disaster: November 2015 Expected timeframe: 18 months; end date 22 May 2017. Operation start date: 22 November 2015 Operation Budget: 560,214, Swiss francs, of which 41 per cent was covered (230,533 Swiss francs). Host National Societies presence (n° of volunteers, staff, branches): The Costa Rican Red Cross (CRRC) has 121 branches grouped into 9 regions. The Costa Rica’s Regions 8 and 5 provided the assistance through its large structure of volunteers, ambulances and vehicles. The Red Cross Society of Panama (RCSP) has 1 national headquarters and 24 branches. At the national level, there are approximately 500 active volunteers. Number of people affected: 17,000 people Number of people assisted: 10,000 people Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: Costa Rican Red Cross, Red Cross Society of Panama, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), and the American Red Cross. Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: In Panama: Ministry of Health, National Civil Protection System (SINAPROC), National Border Service (SENAFRONT), National Navy System (SENAN), International Organization for Migration (IOM), Christian Pastoral (PASOC), Ministry of Interior, Immigration Service, Social Security Service, protestant churches, civil society, private sector (farmers), and Caritas Panama, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN-OCHA). In Costa Rica: National Commission for Risk Prevention and Emergency Assistance (CNE) along with all the institutions that comprise it, Ministry of Health, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), and United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), National Child Welfare Board (PANI) and Caritas Costa Rica. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Bees in urban landscapes: An investigation of habitat utilization Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0gp9j2q7 Author Wojcik, Victoria A. Publication Date 2009 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Bees in urban landscapes: An investigation of habitat utilization By Victoria Agatha Wojcik A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science, Policy, & Management in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Joe R. McBride, Chair Professor Gregory S. Biging Professor Louise A. Mozingo Fall 2009 Bees in urban landscapes: An investigation of habitat utilization © 2009 by Victoria Agatha Wojcik ABSTRACT Bees in urban landscapes: An investigation of habitat utilization by Victoria Agatha Wojcik Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science, Policy, & Management University of California, Berkeley Professor Joe R. McBride, Chair Bees are one of the key groups of anthophilies that make use of the floral resources present within urban landscapes. The ecological patterns of bees in cities are under further investigation in this dissertation work in an effort to build knowledge capacity that can be applied to management and conservation. Seasonal occurrence patterns are common among bees and their floral resources in wildland habitats. To investigate the nature of these phenological interactions in cities, bee visitation to a constructed floral resource base in Berkeley, California was monitored in the first year of garden development. The constructed habitat was used by nearly one-third of the locally known bee species. -

NOTES on COSTA RICAN BIRDS Time Most of the Marshes Dry up and Trees on Upland Sites Lose Their Leaves

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS NOTES ON COSTA RICAN BIRDS time most of the marshes dry up and trees on upland sites lose their leaves. In Costa Rica, this dry season GORDON H. ORIANS is known as “summer,” but in this paper we use the AND terms “winter” and “summer” to refer to winter and DENNIS R. PAULSON summer months of the North Temperate Zone. Department of Zoology Located in the lowland basin of the Rio Tempisque, University of Washington the Taboga region supports more mesic vegetation Seattle, Washington 98105 than the more elevated parts of Guanacaste Province. Originally the area must have been nearly covered The authors spent 29 June 1966 to 20 August 1967 with forest. In the river bottoms a tall, dense, largely in Costa Rica, primarily studying the ecology of Red- evergreen forest was probably the dominant vegetation. winged Blackbirds (Age&s phoeniceus) and insects The hillsides supported a primarily deciduous forest in the marshes of the seasonally dry lowlands of Guana- of lower stature. During the dry season the two caste Province. During this period many parts of the forest types are very different, with the hillside forests country were visited in exploratory trips for other pur- being exposed to extremes of temperature, wind, and poses. The Costa Rican avifauna is better known than desiccation and the bottomland forests retaining much that of any other tropical American country, thanks of their wet-season aspect. At present only scattered esoeciallv to the work of Slud ( 1964). This substantial remnants of the original forest remain, most of them fund of. -

DRAFT Environmental Profile the Republic Costa Rica Prepared By

Draft Environmental Profile of The Republic of Costa Rica Item Type text; Book; Report Authors Silliman, James R.; University of Arizona. Arid Lands Information Center. Publisher U.S. Man and the Biosphere Secretariat, Department of State (Washington, D.C.) Download date 26/09/2021 22:54:13 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/228164 DRAFT Environmental Profile of The Republic of Costa Rica prepared by the Arid Lands Information Center Office of Arid Lands Studies University of Arizona Tucson, Arizona 85721 AID RSSA SA /TOA 77 -1 National Park Service Contract No. CX- 0001 -0 -0003 with U.S. Man and the Biosphere Secretariat Department of State Washington, D.C. July 1981 - Dr. James Silliman, Compiler - c /i THE UNITEDSTATES NATION)IL COMMITTEE FOR MAN AND THE BIOSPHERE art Department of State, IO /UCS ria WASHINGTON. O. C. 2052C An Introductory Note on Draft Environmental Profiles: The attached draft environmental report has been prepared under a contract between the U.S. Agency for International Development(A.I.D.), Office of Science and Technology (DS /ST) and the U.S. Man and the Bio- sphere (MAB) Program. It is a preliminary review of information avail- able in the United States on the status of the environment and the natural resources of the identified country and is one of a series of similar studies now underway on countries which receive U.S. bilateral assistance. This report is the first step in a process to develop better in- formation for the A.I.D. Mission, for host country officials, and others on the environmental situation in specific countries and begins to identify the most critical areas of concern. -

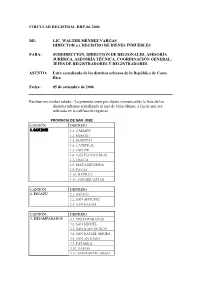

Circular Registral Drp-06-2006

CIRCULAR REGISTRAL DRP-06-2006 DE: LIC. WALTER MÉNDEZ VARGAS DIRECTOR a.i. REGISTRO DE BIENES INMUEBLES PARA: SUBDIRECCIÓN, DIRECCIÓN DE REGIONALES, ASESORÍA JURÍDICA, ASEOSRÍA TÉCNICA, COORDINACIÓN GENERAL, JEFES DE REGISTRADORES Y REGISTRADORES. ASUNTO: Lista actualizada de los distritos urbanos de la República de Costa Rica Fecha: 05 de setiembre de 2006 Reciban mi cordial saludo. La presente tiene por objeto comunicarles la lista de los distritos urbanos actualizada al mes de Julio último, a fin de que sea utilizada en la califiación registral. PROVINCIA DE SAN JOSE CANTÓN DISTRITO 1. SAN JOSE 1.1. CARMEN 1.2. MERCED 1.3. HOSPITAL 1.4. CATEDRAL 1.5. ZAPOTE 1.6. SAN FCO DOS RIOS 1.7. URUCA 1.8. MATA REDONDA 1.9. PAVAS 1.10. HATILLO 1.11. SAN SEBASTIAN CANTÓN DISTRITO 2. ESCAZU 2.1. ESCAZU 2.2. SAN ANTONIO 2.3. SAN RAFAEL CANTÓN DISTRITO 3. DESAMPARADOS 3.1. DESAMPARADOS 3.2. SAN MIGUEL 3.3. SAN JUAN DE DIOS 3.4. SAN RAFAEL ARRIBA 3.5. SAN ANTONIO 3.7. PATARRA 3.10. DAMAS 3.11. SAN RAFAEL ABAJO 3.12. GRAVILIAS CANTÓN DISTRITO 4. PURISCAL 4.1. SANTIAGO CANTÓN DISTRITO 5. TARRAZU 5.1. SAN MARCOS CANTÓN DISTRITO 6. ASERRI 6.1. ASERRI 6.2. TARBACA (PRAGA) 6.3. VUELTA JORCO 6.4. SAN GABRIEL 6.5.LEGUA 6.6. MONTERREY CANTÓN DISTRITO 7. MORA 7.1 COLON CANTÓN DISTRITO 8. GOICOECHEA 8.1.GUADALUPE 8.2. SAN FRANCISCO 8.3. CALLE BLANCOS 8.4. MATA PLATANO 8.5. IPIS 8.6. RANCHO REDONDO CANTÓN DISTRITO 9. -

Readiness-Proposals-Costa-Rica-Unep-Adaptation-Planning.Pdf

with UNEP for the Republic of Costa Rica 10 October 2018 | Adaptation Planning READINESS AND PREPARATORY SUPPORT PROPOSAL TEMPLATE PAGE 1 OF 50 | Ver. 15 June 2017 Readiness and Preparatory Support Proposal How to complete this document? - A Readiness Guidebook is available to provide information on how to access funding under the GCF Readiness and Preparatory Support programme. It should be consulted to assist in the completion of this proposal template. - This document should be completed by National Designated Authorities (NDAs) or focal points with support from their delivery partners where relevant. - Please be concise. If you need to include any additional information, please attach it to the proposal. - Information on the indicative list of activities eligible for readiness and preparatory support and the process for the submission, review and approval of this proposal can be found on pages 11-13 of the guidebook. - For the final version submitted to GCF Secretariat, please delete all instructions indicated in italics in this template and provide information in regular text (not italics). Where to get support? - If you are not sure how to complete this document, or require support, please send an e-mail to [email protected]. We will aim to get back to you within 48 hours. - You can also complete as much of this document as you can and then send it to coun- [email protected]. We will get back to you within 5 working days to discuss your submission and the way forward. Note: Environmental and Social Safeguards and Gender Throughout this document, when answering questions and providing details, please make sure to pay special attention to environmental, social and gender issues, particularly to the situation of vulnerable populations, including women and men. -

Documento Completo

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE APRENDIZAJE DE COSTA RICA ESTUDIO DE PROSPECCIÓN DE MERCADOS: ALTURA GUANACASTECA Unidad PYME - Gerencia General Kenneth Acuña Segura Diego Solís Barrantes Oscar Solís Salas Mario Villamizar Rodríguez 2012 Contenido I. Introducción ................................................................................................................................ 5 II. Objetivos ..................................................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Objetivo General ....................................................................................................................... 7 2.2 Objetivos Específicos ................................................................................................................ 7 III. Ubicación Geográfica .............................................................................................................. 8 IV. Perfil cantonal ............................................................................................................................... 9 4.1 Abangares .................................................................................................................................. 9 4.2 Bagaces ................................................................................................................................... 10 4.3 Cañas ....................................................................................................................................... 10 4.4 Tilarán -

ABSTRACT ARRIAGADA, RODRIGO ANTONIO. Estimating Profitability

ABSTRACT ARRIAGADA, RODRIGO ANTONIO. Estimating profitability and fertilizer demand for rice production around the Palo Verde National Park, Costa Rica. (Under the direction of Dr. Fred Cubbage and Dr. Erin Sills). Rice cultivation is intensively cultivated in some regions of Costa Rica thanks to the establishment of several irrigation projects. This is especially important for the case of several agricultural communities that cultivate their land around the Palo Verde National Park, where the development of the Arenal-Tempisque Irrigation project has brought prosperity to the local farmers. This study made a detailed description of the current rice production system used around Palo Verde by identifying the variable and fixed inputs involved in the rice production. This study included household information of three agricultural settlements. This research also included the estimation of a profit function associated with rice production in this area and the estimation of a fertilizer demand function. Risk analysis was also included to analyze different policy scenarios and determine future fertilizer consumption. Throughout the statistical description of the current rice production system, no statistically significant differences where found among the three communities included. The estimated profit function determined that seed price and capital intensity are significant whereas for the case of the fertilizer demand function rice production, seed price and fertilizer price resulted to be significant. Risk analysis showed the important impact of the current tariff application on imported rice on profits. Regarding the different policy scenarios evaluated to discourage the fertilizer use in this region of Costa Rica, direct intervention on fertilizer price (tax application) has the greatest impact on reduction of fertilizer consumption. -

Sucursales Correos De Costa Rica

SUCURSALES CORREOS DE COSTA RICA Oficina Código Dirección Sector 27 de Abril 5153 Costado sur de la Plaza. Guanacaste, Santa Cruz, Veintisiete de Abril. 50303 Resto del País Acosta 1500 Costado Este de la Iglesia Católica, contiguo a Guardia de Asistencia Rural, San GAM Ignacio, Acosta, San José 11201 Central 1000 Frente Club Unión. San José, San Jose, Merced. 10102 GAM Aguas Zarcas 4433 De la Iglesia Católica, 100 metros este y 25 metros sur. Alajuela, San Carlos, Resto del País Aguas Zarcas. 21004 Alajuela 4050 Calle 5 Avenida 1. Alajuela, Alajuela. 20101 GAM Alajuelita 1400 De la iglesia Católica 25 metros al sur San José, Alajuelita, Alajuelita. 11001 GAM Asamblea 1013 Edificio Central Asamblea Legislativa San José, San Jose, Carmen. 10101 GAM Legislativa Aserrí 1450 Del Liceo de Aserrí, 50 metros al norte. San José, Aserrí, Aserrí. 10601 GAM Atenas 4013 De la esquina sureste de el Mercado, 30 metros este. Alajuela, Atenas, Atenas. Resto del País 20501 Bagaces 5750 Contiguo a la Guardia de Asistencia Rural. Guanacaste, Bagaces, Bagaces. Resto del País 50401 Barranca 5450 Frente a Bodegas de Incoop. Puntarenas, Puntarenas, Barranca. 60108 Resto del País Barrio México 1005 De la plaza de deportes 50 metros norte y 25 metros este, San José, San José, GAM Merced. 10102 Barrio San José de 4030 De la iglesia Católica, 200 metros oeste. Alajuela, Alajuela , San José. 20102 GAM Alajuela Barva de Heredia 3011 Calle 4, Avenida 6. Heredia, Barva, Barva. 40201 GAM Bataán 7251 Frente a la parada de Buses. Limón, Matina, Batan. 70502 Resto del País Boca de Arenal 4407 De la Iglesia Católica, 200 metros sur.