Statutory Estoppel by Deed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Promissory Estoppel, the Civil Law, and the Mixed Jurisdiction

Maurer School of Law: Indiana University Digital Repository @ Maurer Law Articles by Maurer Faculty Faculty Scholarship 1998 Comparative Law in Action: Promissory Estoppel, the Civil Law, and the Mixed Jurisdiction David V. Snyder Indiana University School of Law - Bloomington Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub Part of the Civil Law Commons, and the Contracts Commons Recommended Citation Snyder, David V., "Comparative Law in Action: Promissory Estoppel, the Civil Law, and the Mixed Jurisdiction" (1998). Articles by Maurer Faculty. 2297. https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub/2297 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by Maurer Faculty by an authorized administrator of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMPARATIVE LAW IN ACTION: PROMISSORY ESTOPPEL, THE CIVIL LAW, AND THE MIXED JURISDICTION David V. Snyder* "Touching estoppels, which is an excellent and curious kind of learning. .. I. PROMISSORY ESTOPPEL IN A MIXED JURISDICTION Promissory estoppel, a quintessential creature of the common law, is ordinarily thought to be unknown to the civil law. Arising at first through a surreptitious undercurrent of American case law, promissory estoppel was eventually rationalized in the Restatement of Contracts (Restatement)2 as a necessary adjunct to the bargain theory of consideration. The civil law, with its flexible notion of causa or cause, is free from the constraints of the consideration doctrine. The civil law should not need promissory estoppel. At least initially, the common law and the civil law would appear as disparate in this area as anywhere, and comparative lawyers would be confined to observations about two systems that never meet. -

Estoppel in Property Law Stewart E

Nebraska Law Review Volume 77 | Issue 4 Article 8 1998 Estoppel in Property Law Stewart E. Sterk Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr Recommended Citation Stewart E. Sterk, Estoppel in Property Law, 77 Neb. L. Rev. (1998) Available at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr/vol77/iss4/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Stewart E. Sterk* Estoppel in Property Law TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction .......................................... 756 II. Land Transfers ....................................... 759 A. Inadequate Writings .............................. 760 B. Oral "Agreements". ............................... 764 III. Servitudes by Estoppel ................................ 769 A. Representations by Sellers or Developers .......... 769 B. Representations by Neighbors ..................... 776 C. The Restatement .................................. 784 IV. Termination of Servitudes ............................. 784 V. Boundary Disputes .................................... 788 A. Estoppel Against a True Owner .................... 788 1. By the True Owner's Representations .......... 788 2. By Physical Barriers and Improvements Without Representations ............................... 791 B. Estoppel to Claim Adverse Possession -

October 2017 Insurance Law Alert

Insurance Law Alert October 2017 In This Issue Pennsylvania Supreme Court Rejects Motive Requirement For Statutory Bad Faith Claims Addressing a matter of first impression, the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania rejected an “ill-will” or motive requirement for statutory bad faith claims against an insurer. Rancosky v. Washington National Ins. Co., 2017 WL 4296351 (Pa. Sept. 28, 2017). (Click here for full article) No Coverage Where Policyholder Failed To Meet Its Burden To Allocate “Simpson Thacher Damages, Says Second Circuit has many litigators The Second Circuit ruled that although a liability policy covered a portion of losses arising from who are very experienced faulty construction claims, the insurer had no duty to indemnify based on the policyholder’s in handling complex, inability to allocate the underlying jury verdict between covered and non-covered losses. Univo multi-faceted litigation v. Harleysville Worcester Ins. Co., 2017 WL 4127538 (2d Cir. Sept. 19, 2017). (Click here for involving novel issues.” full article) –Benchmark 2018 quoting a client Second Circuit Rules That Statutory Prejudgment Interest Begins To Accrue On Date Of Sworn Loss The Second Circuit ruled that statutory prejudgment interest begins to accrue when a sworn proof of loss is submitted, not when the policyholder has fulfilled conditions precedent to coverage. Warehouse Wines and Spirits v. Travelers Prop. Cas. Co. of Am., 2017 WL 4227943 (2d Cir. Sept. 21, 2107). (Click here for full article) Applying Nevada Law, Second Circuit Rules That Insured v. Insured Exclusion Unambiguously Bars Coverage For Director’s Suit The Second Circuit ruled that under Nevada law, an insured v. -

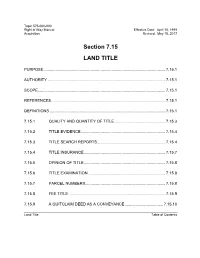

Right of Way Manual, Section 4.1, Land Title

Topic 575-000-000 Right of Way Manual Effective Date: April 15, 1999 Acquisition Revised: May 18, 2017 Section 7.15 LAND TITLE PURPOSE ............................................................................................................... 7.15.1 AUTHORITY ........................................................................................................... 7.15.1 SCOPE .................................................................................................................... 7.15.1 REFERENCES ........................................................................................................ 7.15.1 DEFINITIONS ......................................................................................................... 7.15.1 7.15.1 QUALITY AND QUANTITY OF TITLE .............................................. 7.15.3 7.15.2 TITLE EVIDENCE ............................................................................. 7.15.4 7.15.3 TITLE SEARCH REPORTS .............................................................. 7.15.4 7.15.4 TITLE INSURANCE .......................................................................... 7.15.7 7.15.5 OPINION OF TITLE .......................................................................... 7.15.8 7.15.6 TITLE EXAMINATION ...................................................................... 7.15.8 7.15.7 PARCEL NUMBERS......................................................................... 7.15.8 7.15.8 FEE TITLE ....................................................................................... -

MINERVA SURGICAL, INC. V. HOLOGIC, INC., ET AL

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2020 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus MINERVA SURGICAL, INC. v. HOLOGIC, INC., ET AL. CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FEDERAL CIRCUIT No. 20–440. Argued April 21, 2021—Decided June 29, 2021 In the late 1990s, Csaba Truckai invented a device to treat abnormal uterine bleeding. The device, known as the NovaSure System, uses a moisture-permeable applicator head to destroy targeted cells in the uterine lining. Truckai filed a patent application and later assigned the application, along with any future continuation applications, to his company, Novacept, Inc. The PTO issued a patent for the device. No- vacept, along with its portfolio of patents and patent applications, was eventually acquired by respondent Hologic, Inc. In 2008, Truckai founded petitioner Minerva Surgical, Inc. There, he developed a sup- posedly improved device to treat abnormal uterine bleeding. Called the Minerva Endometrial Ablation System, the new device uses a moisture-impermeable applicator head to remove cells in the uterine lining. The PTO issued a patent, and the FDA approved the device for commercial sale. Meanwhile, Hologic filed a continuation application with the PTO, seeking to add claims to its patent for the NovaSure System. -

The Doctrine of After-Acquired Title

SMU Law Review Volume 11 Issue 2 Article 8 1957 The Doctrine of After-Acquired Title Charles Robert Dickenson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation Charles Robert Dickenson, Comment, The Doctrine of After-Acquired Title, 11 SW L.J. 217 (1957) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol11/iss2/8 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. THE DOCTRINE OF AFTER-ACQUIRED TITLE INTRODUCTION This Comment will discuss briefly some of the problems which can arise when one person attempts by a valid instrument to convey more title than he actually has and subsequently acquires the title which he had purported to convey. Historically, in such a case the grantor is estopped to assert his after-acquired title against his grantee.' It has been said that this result is achieved through estoppel by deed rather than by estoppel in pais;' and that, therefore, there is no neces- sity for an adjudication of the rights of the parties in such a case;$ and that there is no necessity for showing a change in position of the party asserting the estoppel.4 Tiffany states that there is no necessity of regarding the after- acquired title as actually passing to the grantee.' However, there are numerous decisions and dicta in this country to the effect that the conveyance actually passes the grantor's after-acquired legal title to the grantee.! There have been,' and still are,' a number of statutory provisions to this effect in various states. -

The Scope of Title Examination in West Virginia: Can Reasonable Minds Differ

Volume 98 Issue 2 Article 4 January 1996 The Scope of Title Examination in West Virginia: Can Reasonable Minds Differ John W. Fisher II West Virginia University College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvlr Part of the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation John W. Fisher II, The Scope of Title Examination in West Virginia: Can Reasonable Minds Differ, 98 W. Va. L. Rev. (1996). Available at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvlr/vol98/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the WVU College of Law at The Research Repository @ WVU. It has been accepted for inclusion in West Virginia Law Review by an authorized editor of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fisher: The Scope of Title Examination in West Virginia: Can Reasonable M WEST VIRGINIA LAW REVIEW Volume 98 Winter 1996 Number 2 THE SCOPE OF TITLE EXAMINATION IN WEST VIRGINIA: CAN REASONABLE MINDS DIFFER? JOHN W. FISHER, II* I. INTRODUCTION ........................... 450 II. THE RECORDING ACTS ...................... 453 A. In the Beginning ....................... 453 B. Classifying the Early Recording Acts ............. 454 C. The West Virginia Statutes ................... 456 D. The West Virginia Recording Acts: The Aegis Afforded BFP'sfor Value ................. 459 E. The West Virginia Recording Acts: "Notice" is Not a Hindrance to "Creditors"................ 469 F. The West Virginia Recording Acts: While "Mort- gagees" are "Purchasers" Under the Statutes, Not All "Creditors" are "Creditors"............. 472 III. ESTABLISHING THE CHAIN OF TITLE ............. 474 IV. -

Bona Fide Purchaser--Without Title John E

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Kentucky Kentucky Law Journal Volume 36 | Issue 2 Article 2 1948 Bona Fide Purchaser--Without Title John E. Howe Creighton University Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Howe, John E. (1948) "Bona Fide Purchaser--Without Title," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 36 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol36/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BONA FIDE PURCHASER-WITHOUT TITLE1 By JoHN E. HoWEv The legal mind in time of confusion resorts to the use of ancient maxims and Latin phrases in an effort to bring order from chaos. Unless that mind has a fundamental traming m Latin and Legal History-and few minds have such training- the use of such material tends to further mire the person in the depths of misunderstanding. Judicial decisions based on such reasoning are entirely worthless, as the propounders themselves fail to have a basic concept of the idea or thought that is being advanced. If we seek further we will find that it is not uncommon for the teacher, attorney and student of law to justify decisions of the courts through the use of these phrases. -

“Clean Hands” Doctrine

Announcing the “Clean Hands” Doctrine T. Leigh Anenson, J.D., LL.M, Ph.D.* This Article offers an analysis of the “clean hands” doctrine (unclean hands), a defense that traditionally bars the equitable relief otherwise available in litigation. The doctrine spans every conceivable controversy and effectively eliminates rights. A number of state and federal courts no longer restrict unclean hands to equitable remedies or preserve the substantive version of the defense. It has also been assimilated into statutory law. The defense is additionally reproducing and multiplying into more distinctive doctrines, thus magnifying its impact. Despite its approval in the courts, the equitable defense of unclean hands has been largely disregarded or simply disparaged since the last century. Prior research on unclean hands divided the defense into topical areas of the law. Consistent with this approach, the conclusion reached was that it lacked cohesion and shared properties. This study sees things differently. It offers a common language to help avoid compartmentalization along with a unified framework to provide a more precise way of understanding the defense. Advancing an overarching theory and structure of the defense should better clarify not only when the doctrine should be allowed, but also why it may be applied differently in different circumstances. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 1829 I. PHILOSOPHY OF EQUITY AND UNCLEAN HANDS ...................... 1837 * Copyright © 2018 T. Leigh Anenson. Professor of Business Law, University of Maryland; Associate Director, Center for the Study of Business Ethics, Regulation, and Crime; Of Counsel, Reminger Co., L.P.A; [email protected]. Thanks to the participants in the Discussion Group on the Law of Equity at the 2017 Southeastern Association of Law Schools Annual Conference, the 2017 International Academy of Legal Studies in Business Annual Conference, and the 2018 Pacific Southwest Academy of Legal Studies in Business Annual Conference. -

THE AFTER-ACQUIRED PROPERTY CLAUSE Davm COHEN T and ALBERT B

April, 1939 University of Pennsylvania Law Review And American Law Register FOUNDED 1852 Copyright 1939, by the University of Pennsylvania VOLUME 87 APRIL, 1939 No. 6 THE AFTER-ACQUIRED PROPERTY CLAUSE DAVm COHEN t AND ALBERT B. GERBER $ At common law property to be created or acquired in the future could not be transferred or encumbered prior to the creation or ac- quisition of the property.1 Illustrative of the constant striving to make future assets available for present purposes was the attempt of com- mon-law lawyers to add to the conveyances of the day the words: "Quae quovismodo in futurum habere potero." 2 But, as Littleton says, these words were "void in law". The reasoning upon which the rule was based was simple--"A man cannot grant or charge that which he hath not." 3 This infallible bit of syllogistic logic received its first breakdown in the famous case of Grantham v. Hawley,4 the parent of the fictitious doctrine of "potential existence". Briefly stated, this prin- ciple permits the sale 5 or encumbrance of future personal property 6 t B. S. in Ed., x934, LL. B., 1937, Gowen Memorial Fellow, 1937-8, University of Pennsylvania; member of the Philadelphia bar; assistant counsel, Rural Electrification Administration. t B. S. in Ed., 1934, LL. B., 1937, Gowen Memorial Fellow, 1937-8, University of Pennsylvania; member of the Philadelphia bar; assistant counsel, Rural Electrification Administration. I. See 3 TIFFANY, REAL PROPERTY (2d ed. i92o) 2368. 2. The quotation in full reads: "Also, these words, which are commonly put in such releases, scil. -

Title Examinations and Title Issues

CHAPTER 7 Title Examinations and Title Issues R. Prescott Jaunich, Esq. Downs Rachlin Martin PLLC, Burlington Timothy S. Sampson, Esq. Downs Rachlin Martin PLLC, Burlington § 7.1 Introduction ................................................................................. 7–1 § 7.2 Marketable Title .......................................................................... 7–4 § 7.2.1 Vermont Title Standards ............................................... 7–4 § 7.2.2 Common Law Marketable Title—Permits as Encumbrances ............................................................... 7–6 § 7.2.3 Vermont Marketable Record Title Act ........................ 7–10 (a) Person ................................................................ 7–11 (b) Unbroken Chain of Title .................................... 7–11 (c) Conveyance ....................................................... 7–12 (d) Preserved Claims Under the Act ........................ 7–13 § 7.3 Conveyancing Requirements .................................................... 7–15 § 7.3.1 Vermont Deed Customs .............................................. 7–15 § 7.3.2 Deeds by Trustees and Deeds to Trust ........................ 7–17 § 7.3.3 Deeds by Executors, Administrators and Guardians .. 7–17 § 7.3.4 Deeds by Divorce Judgment ....................................... 7–18 § 7.3.5 Probate Decree ............................................................ 7–18 § 7.4 Identifying the Real Estate and Property Descriptions .......... 7–18 § 7.4.1 Reference to Prior Deeds and Instruments -

Unconscionability As an Underlying Concept in Equity

THE DENNING LAW JOURNAL UNCONSCIONABILITY AS A UNIFYING CONCEPT IN EQUITY Mark Pawlowski* ABSTRACT This article seeks to examine the extent to which a unified concept of unconscionability can be used to rationalise related doctrines of equity, in particular, in the areas of (1) unconscionable bargains, undue influence and duress (2) proprietary estoppel (3) knowing receipt liability and (4) relief against forfeitures. The conclusion is that such a process of amalgamation may provide a principled doctrinal basis for equity’s intervention which has already found favour in the English courts. INTRODUCTION A recent discernible trend in equity has been the willingness of the English courts to adopt a broader-based doctrine of unconscionability as underlying proprietary estoppel claims and the personal liability of a stranger to a trust who has knowingly received trust property in breach of trust. The decisions in Gillett v Holt,1 Jennings v Rice2 and Campbell v Griffin3 in the context of proprietary estoppel and Bank of Credit and Commerce International (Overseas) Ltd v Akindele4 on the subject of receipt liability, demonstrate the judiciary’s growing recognition that the concept of unconscionability provides a useful mechanism for affording equitable relief against the strict insistence on legal rights or unfair and oppressive conduct. This, in turn, prompts the question whether there are other areas which would benefit from a rationalisation of principles under the one umbrella of unconscionability. The process of amalgamation, it is submitted, would be particularly useful in areas where there are currently several related (but distinct) doctrines operating together so as to give rise to confusion and overlap in the same field of law.