A Genesis of the Platform Concept: I-Mode and Platform Theory in Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protoculture Addicts

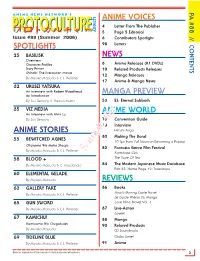

PA #88 // CONTENTS PA A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S ANIME VOICES 4 Letter From The Publisher PROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]-PROTOCULTURE ADDICTS 5 Page 5 Editorial Issue #88 (Summer 2006) 6 Contributors Spotlight SPOTLIGHTS 98 Letters 25 BASILISK NEWS Overview Character Profiles 8 Anime Releases (R1 DVDs) Story Primer 10 Related Products Releases Shinobi: The live-action movie 12 Manga Releases By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 17 Anime & Manga News 32 URUSEI YATSURA An interview with Robert Woodhead MANGA PREVIEW An Introduction By Zac Bertschy & Therron Martin 53 ES: Eternal Sabbath 35 VIZ MEDIA ANIME WORLD An interview with Alvin Lu By Zac Bertschy 73 Convention Guide 78 Interview ANIME STORIES Hitoshi Ariga 80 Making The Band 55 BEWITCHED AGNES 10 Tips from Full Moon on Becoming a Popstar Okusama Wa Maho Shoujo 82 Fantasia Genre Film Festival By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Sample fileKamikaze Girls 58 BLOOD + The Taste Of Tea By Miyako Matsuda & C. Macdonald 84 The Modern Japanese Music Database Part 35: Home Page 19: Triceratops 60 ELEMENTAL GELADE By Miyako Matsuda REVIEWS 63 GALLERY FAKE 86 Books Howl’s Moving Castle Novel By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Le Guide Phénix Du Manga 65 GUN SWORD Love Hina, Novel Vol. 1 By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 87 Live-Action Lorelei 67 KAMICHU! 88 Manga Kamisama Wa Chugakusei 90 Related Products By Miyako Matsuda CD Soundtracks 69 TIDELINE BLUE Otaku Unite! By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 91 Anime More on: www.protoculture-mag.com & www.animenewsnetwork.com 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ LETTER FROM THE PUBLISHER A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S PROTOCULTUREPROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]- ADDICTS Over seven years of writing and editing anime reviews, I’ve put a lot of thought into what a Issue #88 (Summer 2006) review should be and should do, as well as what is shouldn’t be and shouldn’t do. -

Continuing Education Catalog

l. TurnOver aNew Leaf University of Colorado at Boulder Continuing Education Falll989 Schedule of Courses, Seminars and Workshops t\'11\~ou can earn'""I"'"'' academic credit at e'IC<'J \e""\, high school mrough graduate school. Credit programs include: sou\det E"ening Credit Classes . For un\'ers\t'i course' atcon'en,ent even'nll hour> Independentindependent StudY studY ptogtaD's by corresJ>Ondence and ind\,;dua\ized .msu,,cuon . \e \S -youcente' \earn {or at home.M•anced Ttaininll in Eng;neer\ng and con>P" t er S c,en«· {Ct\'fECS).Earn a )>lasi<TS degree or graduate credit w\lh courses"'\ •"'"'· d r'"" tJo )'our worksite. '"""'''""'' f.\\\\l\\&l\\\1\\\: t1\'\\\\&atl'\'o po\tsh your si<i\\s '""I"'"'' or acquire neW one.' enhance your current career or e><p\ore another [,eld, eont\nu\nil Educauon offers a full spectrUm of pro grams. )>lost classes offer continu\nll f,ducatio~ Un'ts (CEUs),_lhenabonal standard for recording universil)'-\ev<\ noncred'' course parh<'pauon Or earn an t\chievement Certificate in: commercialeonwuter .<pp\\cat\oOS Design and Computer Graphics ~anagement Development \llf\\\\\1 fll' \1'""'"1' s St\1: 'fhe broad ranll• of noncredit course.' offered at con••~'C"' evening and . tto\\&"''"'weekend bouTS mean t""""' no tests, no grades, and no prerequ>S'tes- ~et noncred'' courses. enco,;,passinll bolh personal and prof~sional interests. are taught bY highlY qual\f\ed inStrUc\oTS- Eni<>Y non-comP•"""' \earnmll w,\h o\heTS who share -your interests. t\\l\\11p\eaSC \et us """ know. -

Discover Wisconsin

AN UPDATE ON THE BUSINESS CLIMATE, RECREATIONAL RESOURCES AND FAMILY LIVING ENVIRONMENT IN VILAS AND ONEIDA COUNTIES 22 00 11 77 PROGRESS Discover Wisconsin celebrates 30 years TourismTourism programprogram reachesreaches 500,000500,000 viewersviewers acrossacross thethe MidwestMidwest Great North Bank redesigns brand FinancialFinancial institutioninstitution remainsremains familyfamily ownedowned andand independentindependent Rhinelander Nissan moves to new facility State-of-the-artState-of-the-art sales,sales, serviceservice departmentsdepartments offeredoffered toto customerscustomers AA SPECIALSPECIAL PUBLICATIONPUBLICATION OFOF THETHE VILASVILAS COUNTYCOUNTY NEWS-REVIEWNEWS-REVIEW ANDAND THETHE THREETHREE LAKESLAKES NEWSNEWS Page 2 Progress — 2017 THEAllAll New!New! OPEN FOR BUSINESS StopStop inin andand saysay hihi toto Josh!Josh! GRAND OPENING SERVICE SPECIAL OIL CHANGE $ 95 SPECIAL* 12*Up to 5 quarts, excludes full synthetic and diesel. Expires 3/31/17 Come see our brand-new, state-of-the-art Nissan Service is open Mon.-Fri. 7 a.m. to 5 p.m. Nissan showroom — the only one like it in the Midwest and Sat. 7:30 a.m. to noon 1742 N. Stevens St. Rhinelander, WI • Sales (877) 968-7126 • Service (888) 690-2754 Welcome to Rhinelander Nissan • Parts (888) 658-0259 The brand-new Rhinelander Nissan treats the needs of each individual customer with kid gloves. We know that you have high expectations, and as a car dealer we enjoy the challenge of meeting and We service all cars. exceeding those standards each and every time. Allow us to demonstrate our commitment to excel- lence! Our experienced sales staff is eager to share their knowledge and enthusiasm with you. We en- Make a reservation online! courage you to browse our online inventory, schedule a test drive and investigate financing options. -

Manga Vision: Cultural and Communicative Perspectives / Editors: Sarah Pasfield-Neofitou, Cathy Sell; Queenie Chan, Manga Artist

VISION CULTURAL AND COMMUNICATIVE PERSPECTIVES WITH MANGA ARTIST QUEENIE CHAN EDITED BY SARAH PASFIELD-NEOFITOU AND CATHY SELL MANGA VISION MANGA VISION Cultural and Communicative Perspectives EDITED BY SARAH PASFIELD-NEOFITOU AND CATHY SELL WITH MANGA ARTIST QUEENIE CHAN © Copyright 2016 Copyright of this collection in its entirety is held by Sarah Pasfield-Neofitou and Cathy Sell. Copyright of manga artwork is held by Queenie Chan, unless another artist is explicitly stated as its creator in which case it is held by that artist. Copyright of the individual chapters is held by the respective author(s). All rights reserved. Apart from any uses permitted by Australia’s Copyright Act 1968, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright owners. Inquiries should be directed to the publisher. Monash University Publishing Matheson Library and Information Services Building 40 Exhibition Walk Monash University Clayton, Victoria 3800, Australia www.publishing.monash.edu Monash University Publishing brings to the world publications which advance the best traditions of humane and enlightened thought. Monash University Publishing titles pass through a rigorous process of independent peer review. www.publishing.monash.edu/books/mv-9781925377064.html Series: Cultural Studies Design: Les Thomas Cover image: Queenie Chan National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Title: Manga vision: cultural and communicative perspectives / editors: Sarah Pasfield-Neofitou, Cathy Sell; Queenie Chan, manga artist. ISBN: 9781925377064 (paperback) 9781925377071 (epdf) 9781925377361 (epub) Subjects: Comic books, strips, etc.--Social aspects--Japan. Comic books, strips, etc.--Social aspects. Comic books, strips, etc., in art. Comic books, strips, etc., in education. -

Char's Counterattack © 1998, 2002 Sotsu Agency • Sunrise

TT HH EE AA NN II MM EE && MM AA NN GG AA MM AA GG AA ZZ II NN EE $$ 44 .. 99 55 UU SS // CC AA NN PROTOCULTURE PROTOCULTUREAA DD DD II CC TT SS MAGAZINE www.protoculture-mag.com 7373 •• cosmocosmo wwarriorarrior zerozero •• ccowboyowboy bebopbebop thethe moviemovie •• jojojosjos bizarrebizarre Sample file adventureadventure •• natsunatsu hehe nono totobirabira •• projectproject armsarms •• sakurasakura warswars •• scryedscryed •• slayersslayers premiumpremium •• NEWSNEWS && REVIEWSREVIEWS CHAR’S COUNTERATTACK CHAR’S COUNTERATTACK C o v e r 2 o f 2 Sample file CONTENTS 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ PROTOCULTURE ✾ PRESENTATION ........................................................................................................... 4 STAFF NEWS ANIME & MANGA NEWS: Japan / North America ............................................................... 5, 10 Claude J. Pelletier [CJP] — Publisher / Manager ANIME RELEASES (VHS / DVD) & PRODUCTS (Live-Action, Soundtracks, etc.) .............................. 6 Miyako Matsuda [MM] — Editor / Translator MANGA RELEASES / MANGA SELECTION / MANGA NEWS .......................................................... 7 Martin Ouellette [MO] — Editor JAPANESE DVD (R2) RELEASES .............................................................................................. 9 NEW RELEASES ..................................................................................................................... 11 Contributing Editors Aaron K. Dawe, Asaka Dawe, Keith Dawe Kevin Lillard, Gerry -

Notice of the 11Th Annual Meeting of Shareholders

Securities Code: 3635 June 2, 2020 To Our Shareholders: 1-18-12 Minowa-cho, Kouhoku-ku, Yokohama-shi, Kanagawa KOEI TECMO HOLDINGS CO., LTD. Yoichi Erikawa, President & CEO (Representative Director) Notice of the 11th Annual Meeting of Shareholders The Company hereby notifies shareholders that the 11th Annual Meeting of Shareholders will be held as described below. Recently, self-restraint of leaving home has been requested by the government and prefectural governors to prevent the spread of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). As a result of due consideration to the given situation, we have decided to hold the Annual Meeting of Shareholders following appropriate measures to prevent infection. Also, considering the situation in which self-restraint of leaving home is requested, we strongly suggest that, from the perspective of preventing the spread of infection, you exercise your voting rights in writing or by electromagnetic means (such as on the Internet) in advance if at all possible for this Annual Meeting of Shareholders, and refrain from attending on the date concerned. We kindly request you read the following Reference Document for the Annual Meeting of Shareholders, and exercise your voting rights by any of the methods described in the “Information on Exercise of Voting Right” (pages5 and 6) no later than Wednesday, June 17, 2020 at 6:00 p.m. Date: Thursday, June 18, 2020 at 10:00 a.m. Venue: 3-7 Minatomirai 2-chome, Nishi-ku, Yokohama-shi, Kanagawa The Yokohama Bay Hotel Tokyu 2nd basement, Ambassador’s Ballroom (Please see the “Venue Information Map for the Annual Meeting of Shareholders.”) Purposes: Items to be reported: 1. -

MAG Public Safety Answering Point Managers Group Meeting Agenda

August 2, 2017 TO: Members of the MAG PSAP Managers Group FROM: Domela Finnessey, Surprise Police Department, Chair SUBJECT: MEETING NOTIFICATION AND TRANSMITTAL OF TENTATIVE AGENDA Thursday, August 10, 2017, at 10:00 a.m. MAG Office, Suite 200 - Saguaro Room 302 North 1st Avenue, Phoenix A meeting of the MAG PSAP Managers Group has been scheduled for the time and place noted above. Members of the PSAP Managers Group may attend the meeting either in person, by videoconference, or by telephone conference call. In 1996, the Regional Council approved a simple majority quorum for all MAG advisory committees. If the PSAP Managers Group does not meet the quorum requirement, members who have arrived at the meeting will be instructed a meeting cannot occur and subsequently be dismissed. Your attendance at the meeting is strongly encouraged. Pursuant to Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), MAG does not discriminate on the basis of disability in admissions to or participation in its public meetings. Persons with a disability may request a reasonable accommodation, such as a sign language interpreter, by contacting the MAG office. Requests should be made as early as possible to allow time to arrange the accommodation. If you have any questions regarding the meeting, please contact Liz Graeber, Maricopa Region 9-1-1 Administrator, City of Phoenix Fire, at 602-534-9775, or Nathan Pryor, MAG, at 602-254-6300. MAG PSAP MANAGERS GROUP TENTATIVE AGENDA August 10, 2017 COMMITTEE ACTION REQUESTED 1. Call to Order 2. Call to the Audience 2. Information. An opportunity is provided to the public to address the PSAP Managers Group on items that are not on the agenda that are within the jurisdiction of MAG, or non-action agenda items that are on the agenda for discussion or information only. -

Notice of the 12Th Annual Meeting of Shareholders

Securities Code: 3635 June 1, 2021 To Our Shareholders: 1-18-12 Minowa-cho, Kouhoku-ku, Yokohama-shi, Kanagawa KOEI TECMO HOLDINGS CO., LTD. Yoichi Erikawa, President & CEO (Representative Director) Notice of the 12th Annual Meeting of Shareholders The Company hereby notifies shareholders that the 12th Annual Meeting of Shareholders will be held as described below. Recently, self-restraint of leaving home has been requested by the government and prefectural governors to prevent the spread of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). As a result of due consideration to the given situation, we have decided to hold the Annual Meeting of Shareholders following appropriate measures to prevent infection. Also, considering the situation in which self-restraint of leaving home is requested, we suggest that, from the perspective of preventing the spread of infection, you exercise your voting rights in writing or by electromagnetic means (such as on the Internet) in advance if at all possible for this Annual Meeting of Shareholders, and refrain from attending on the date concerned. We kindly request you read the following Reference Document for the Annual Meeting of Shareholders, and exercise your voting rights by any of the methods described in the “Information on Exercise of Voting Right” (pages6 and 7) no later than Wednesday, June 16, 2021 at 6:00 p.m. Date: Thursday, June 17, 2021 at 10:00 a.m. Venue: 3-7 Minatomirai 2-chome, Nishi-ku, Yokohama-shi, Kanagawa The Yokohama Bay Hotel Tokyu 2nd basement, Ambassador’s Ballroom (Please see the “Venue Information Map for the Annual Meeting of Shareholders.”) Purposes: Items to be reported: 1. -

Notice of the 59Th General Meeting of Shareholders

Securities Code: 9477 June 3, 2013 To Our Shareholders Tatsuo Sato, Representative Director and President KADOKAWA GROUP HOLDINGS, INC. 13-3, 2-chome, Fujimi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo NOTICE OF THE 59TH GENERAL MEETING OF SHAREHOLDERS To the Shareholders of KADOKAWA GROUP HOLDINGS, INC. (the "Group") Taking this occasion, we would like to express our deep gratitude to you for your good offices. You are cordially invited to attend our 59th Annual General Meeting of Shareholders. If you are unable to attend the meeting, you can exercise your voting rights in writing or on the Internet. Please review the attached "Reference Materials on the Exercise of Voting Rights," indicate your approval or disapproval for each of the proposals on the enclosed ballot, paste the protective seal enclosed on the ballot and mail it back to us by 17:00, Friday, June 21, 2013 (JST) or access the website for the exercise of voting rights (http://www.evote.jp/) from a personal computer or mobile phone or smart phone and enter your approval or disapproval for each proposal by 17:00, Friday, June 21, 2013 (JST). Very truly yours, Details 1. Date: 10:00 a.m. on Saturday, June 22, 2013 (The reception of participants in the meeting will begin at 9:00 a.m.) 2. Place: "Rose Room," 9th floor, Tokyo Kaikan 2-1, 3-chome, Marunouchi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 3. Objectives Matters to be reported: 1. Presentation of the Business Report, Consolidated Financial Statements, and Audit Report on the Consolidated Financial Statements by the Independent Auditor and the Board of Auditors for the 59th fiscal year (from April 1, 2012 to March 31, 2013) 2. -

Discourses of War and History in the Japanese Game Kantai Collection and Its Fan Community

Discourses of war and history in the Japanese game Kantai Collection and its fan community Valtteri Vuorikoski [email protected] Master’s Thesis Department of World Cultures, University of Helsinki Tiedekunta/Osasto – Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Laitos – Institution – Department Humanistinen tiedekunta Maailman kulttuurien laitos Tekijä – Författare – Author Valtteri Vuorikoski Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Discourses of war and history in the Japanese game Kantai Collection and its fan community Oppiaine – Läroämne – Subject Itä-Aasian tutkimus Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and year Sivumäärä– Sidoantal – Number of pages Pro gradu -tutkielma Marraskuu 2017 111 Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Tutkielmassa tarkastellaan japanilaista Kantai Collection -laivastosotapeliä ja siihen liittyvä mediakokonaisuutta (media mix) sekä kyseisen mediakokonaisuuden yleisön sen pohjalta tuottamia omakustanteisia fan fiction -teoksia. Kantai Collection -pelin eri versioiden lisäksi tarkastellaan samannimistä animaatiosarjaa, mutta viitataan myös sarjakuva- ja elokuvaversioihin. Fan fiction -teoksia tarkastellaan sekä määrällisesti (N=120) että laadullisesti (N=46). Tarkastelu on kaksivaiheinen. Ensiksi analysoidaan alkuperäisteosten tarinarakenteita ja diskursseja Tyynenmeren sodasta ja Japanin lähihistoriasta soveltaen Michel Foucault’n määrittämää diskurssianalyysia sekä Umberto Econ teoriaa avoimista ja suljetuista teoksista. Toisessa vaiheessa analysoidaan samoin laadullisin menetelmin, miten yleisön tuottamat fan -

Making the Leap Beyond 'Newspaper Companies'

Newspaper Next 2.0 Making the Leap Beyond ‘Newspaper Companies’ February 2008 PRinciPAL AUTHOR AND EDITOR INTRODUCTION AND EXecUTIVE SUmmARY ..................................................................1 Stephen T. Gray SecTION 1: WHAT CAN newsPAPER COMPAnies becOme? ........................................4 Managing Director, Newspaper Next 1. What’s happening now .................................................................................................. 4 Steve Gray was appointed managing director of Newspaper 2. Seeing beyond newspaper companies ..........................................................................6 Next at its inception in September 2005, and led the 3. Pursuing mega-jobs ................................................................................................... 10 project team during the original development phase. Upon CONTENTS SecTION 2: THE N2 CAsebOOK .....................................................................................20 completion of the project’s original report and recommen- Part 1: The new products ...........................................................................................21 2 dations in September 2006, he taught the N approach in Key takeaways ............................................................................................................... 22 dozens of workshops and presentations in the U.S., Canada Summing up ...................................................................................................................26 and overseas, -

Notice of the 9Th Annual Meeting of Shareholders the Company Hereby Invites Shareholders to Attend the 9Th Annual Meeting of Shareholders As Described Below

Securities Code: 3635 June 4, 2018 To Our Shareholders: 1-18-12 Minowa-cho, Kouhoku-ku, Yokohama-shi, Kanagawa KOEI TECMO HOLDINGS CO., LTD. Yoichi Erikawa, President & CEO (Representative Director) Notice of the 9th Annual Meeting of Shareholders The Company hereby invites shareholders to attend the 9th Annual Meeting of Shareholders as described below. If you are unable to attend the meeting on that date, you may also exercise your voting rights in writing or by electromagnetic means (such as on the Internet). We kindly request you read the following Reference Document for the Annual Meeting of Shareholders, and exercise your voting rights by any of the methods described in the “Information on Exercise of Voting Right” (pages 3 and 4) no later than Tuesday, June 19, 2018 at 6:00 p.m. Date: Wednesday, June 20, 2018 at 10:00 a.m. Venue: 3-7 Minatomirai 2-chome, Nishi-ku, Yokohama-shi, Kanagawa The Yokohama Bay Hotel Tokyu 2nd basement, Ambassador’s Ballroom (Please see the “Venue Information Map for the Annual Meeting of Shareholders.”) Purposes: Items to be reported: 1. The business report, the consolidated financial statements and the results of consolidated financial statement audits by the Accounting Auditor and the Audit & Supervisory Board for the 9th business period (April 1, 2017 to March 31, 2018) 2. The non-consolidated financial statements for the 9th business period (April 1, 2017 to March 31, 2018) Items to be resolved: Agenda No. 1: Appropriation of Retained Earnings Agenda No. 2: Election of Eleven (11) Directors Agenda No. 3: Election of One (1) Audit & Supervisory Board Member Agenda No.