CHAPTER 2 the Changing Nature of Corporate Governance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Australian Mirage

An Australian Mirage Author Hoyte, Catherine Published 2004 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School School of Arts, Media and Culture DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/1870 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367545 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au AN AUSTRALIAN MIRAGE by Catherine Ann Hoyte BA(Hons.) This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Griffith University Faculty of Arts School of Arts, Media and Culture August 2003 Statement of Authorship This work has never been previously submitted for a degree or diploma in any university. To the best of my knowledge and belief, this dissertation contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the dissertation itself. Abstract This thesis contains a detailed academic analysis of the complete rise and fall of Christopher Skase and his Qintex group mirage. It uses David Harvey’s ‘Condition of Postmodernity’ to locate the collapse within the Australian political economic context of the period (1974-1989). It does so in order to answer questions about why and how the mirage developed, why and how it failed, and why Skase became the scapegoat for the Australian corporate excesses of the 1980s. I take a multi-disciplinary approach and consider corporate collapse, corporate regulation and the role of accounting, and corporate deviance. Acknowledgments I am very grateful to my principal supervisor, Dr Anthony B. van Fossen, for his inspiration, advice, direction, guidance, and unfailing encouragement throughout the course of this study; and for suggesting Qintex as a case study. -

Official Committee Hansard

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Official Committee Hansard JOINT COMMITTEE ON CORPORATIONS AND FINANCIAL SERVICES Reference: Financial products and services in Australia FRIDAY, 4 SEPTEMBER 2009 SYDNEY BY AUTHORITY OF THE PARLIAMENT INTERNET Hansard transcripts of public hearings are made available on the inter- net when authorised by the committee. The internet address is: http://www.aph.gov.au/hansard To search the parliamentary database, go to: http://parlinfoweb.aph.gov.au JOINT STATUTORY COMMITTEE ON CORPORATIONS AND FINANCIAL SERVICES Friday, 4 September 2009 Members: Mr Ripoll (Chair), Senator Mason (Deputy Chair), Senators Boyce, Farrell, McLucas and Wil- liams and Ms Grierson, Ms Owens, Mr Pearce and Mr Robert Members in attendance: Senators Farrell, McLucas, Mason and Williams and Ms Owens, Mr Pearce and Mr Ripoll Terms of reference for the inquiry: To inquire into and report on: Issues associated with recent financial product and services provider collapses, such as Storm Financial, Opes Prime and other similar collapses, with particular reference to: 1. the role of financial advisers; 2. the general regulatory environment for these products and services; 3. the role played by commission arrangements relating to product sales and advice, including the potential for conflicts of interest, the need for appropriate disclosure, and remuneration models for financial advisers; 4. the role played by marketing and advertising campaigns; 5. the adequacy of licensing arrangements for those who sold the products and services; 6. the appropriateness of information and advice provided to consumers considering investing in those products and services, and how the interests of consumers can best be served; 7. consumer education and understanding of these financial products and services; 8. -

CLA Developments in Corporations Law June 2018

Recent developments in corporate law CLA June Judges series 8 June 2018 Ashley Black A Judge of the Supreme Court of New South Wales Introduction This note reviews several developments in corporations and insolvency law as at June 2018. I first note three recently decided cases as to directors’ duties and oppression, then several cases decided since the introduction of the Insolvency Law Reform Act 2016 (Cth), and then consider important recent case law as to the liquidation of trustee companies and disclaimers of onerous property. I will also refer to an interesting recent example of a freezing order granted in an external administration. I will then note the introduction of a safe harbour from liability for insolvent trading to facilitate corporate restructurings and a stay on the use of ipso facto clauses to amend or terminate contracts with a company that is placed in voluntary administration. I will also refer to recent developments as financial benchmark manipulation and penalties for breach of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). Directors’ duties and oppression Judgment has recently been given in the penalty hearing of the long running proceedings against Mr and Mrs Cassimatis, the directors and sole shareholders of Storm Financial Ltd (“Storm”). In the liability judgment 1, Edelman J held that Mr and Mrs Cassimatis had contravened s 180 of the Corporations Act in exercising their powers as directors of Storm in a manner that caused or permitted (by omission) inappropriate advice to be given by that entity to a particular class of investors who were, inter alia, retired or close to retirement and had little or no prospect of rebuilding their financial position if they suffered substantial loss. -

Copyrighted Material

i i i “BMIndex_Final_print” — 2019/7/30 — 9:19 — page 391 — #1 i INDEX AASB see Australian Accounting AUASB see Auditing and Assurance business judgment rule 212–214, 222 Standards Board Standards Board using the defence 213–214 ABN see Australian Business Number Auditing and Assurance Standards Board business name registration 40, 44 absolute liability 135, 136 (AUASB) 276 business names 40 accountability 174 auditor’s report 286 display and use of 42 ACN see Australian Company Number Australian Accounting Standards Board registration 40–41 acquiescence 122, 124 (AASB) 275–276 restrictions 41–42 active promoters 100 Australian Business Number (ABN) business organisations actual authority 120, 136 61, 77 business names 40 express 120–121 Australian Company Number (ACN) business structure 3–7 implied 121–122 58, 60, 61 companies 27–30 adjourned meetings 154 Australian Prudential Regulation cooperatives 30–34 Aequitas Ltd v Sparad No 100 Ltd 100 Authority (APRA) 32 hybrid business structures 37–40 agency costs 173, 194 Australian Securities and Investments incorporated association 34–37 agency theory 115, 137, 173–174, 194 Commission (ASIC) 50, 73, 143, joint ventures 17–19 agenda of meetings 159, 168 175, 200, 201, 228, 274–275 partnerships 10–17 AGM see annual general meeting Australian Securities and Investments sole traders 7–10 agricultural cooperatives 33 Commission Act 2001 (ASIC Act) trusts 20–27 Airpeak Pty Ltd & Ors v Jetstream 50 business structure 3–7 Aircraft Ltd & Anor (1997) 318 Australian Securities and Investments Andy -

Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254)

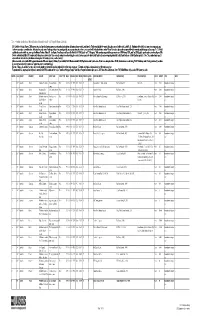

Table1.—Attribute data for the map "Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254). [The United States Geological Survey (USGS) surveys international mineral industries to generate statistics on the global production, distribution, and resources of industrial minerals. This directory highlights the economically significant mineral facilities of Asia and the Pacific. Distribution of these facilities is shown on the accompanying map. Each record represents one commodity and one facility type for a single location. Facility types include mines, oil and gas fields, and processing plants such as refineries, smelters, and mills. Facility identification numbers (“Position”) are ordered alphabetically by country, followed by commodity, and then by capacity (descending). The “Year” field establishes the year for which the data were reported in Minerals Yearbook, Volume III – Area Reports: Mineral Industries of Asia and the Pacific. In the “DMS Latitiude” and “DMS Longitude” fields, coordinates are provided in degree-minute-second (DMS) format; “DD Latitude” and “DD Longitude” provide coordinates in decimal degrees (DD). Data were converted from DMS to DD. Coordinates reflect the most precise data available. Where necessary, coordinates are estimated using the nearest city or other administrative district.“Status” indicates the most recent operating status of the facility. Closed facilities are excluded from this report. In the “Notes” field, combined annual capacity represents the total of more facilities, plus additional -

Cba Financial Planning Scandal

July 2014 SMSF Specialists Investment Management Financial Planning Accounting Thompson. Both Phil and Alastair each have over 30 years prac- ticing experience and are assisted by two recent accounting IN THIS ISSUE graduates, Kushal Sharma and Ivan Yeung as well as two further • GFM Accounting – get organised early! support staff, Miryam Schejtmen and Shimla Prasad. • CBA Financial Planning Scandal The constant frustration of many of our clients is that their • 2013/14 Financial Year – Another Bumper Year current accountants do not provide pro-active accounting • Jack Watt – Client of GFM since 1996 advice, rather “they go through the motions” without any real • Deeming of Account Based Pensions from thought of tax minimisation. The GFM Gruchy team work hard 1 January 2015 to ensure you get pro-active accounting. It is critically important you ensure your accounting affairs are well • Staff Profile – Denise Slattery structured and managed and you pay the least amount of • Upcoming seminar - Monday 18th August 2014 at tax possible. 12.00 noon – Estate Planning Creating Certainty • Superannuation, Centrelink Age Pension benefits Our accounting firm is not only able to help with personal & Personal Taxation impact from the 2014 Federal returns but can also assist with the following services: Budget – Seminar June 2014 • Partnership Returns • Upcoming new website launch • Family Trust Returns • “Best Interests Duty” – Who is your financial adviser • Company Tax Returns really working for? • Wealthy investors favour SMSF’s • Business Activity Statements • Do you know where you are going? • Bookkeeping Services • Compulsory Superannuation Guarantee Charge • Financial Statements With the end of financial year 2013/14 just finished, we are in a strong position to be able to assist you with your personal tax GFM ACCOUNTING: returns for those that want to get organised early and possibly GET ORGANISED EARLY! get their refund ASAP. -

ASIC 2007–2007 Annual Report

ASIC ANNU ASIC A L REPO R T 07–08 ASIC acHIEVEMENTS RECOGNisED 2007–08 Annual reporting Other communication Environmental management ASIC Annual Report 2006–07 Annual Report Awards from the Society of ASIC’s Sydney site is certified to Gold Award 2008 for overall Technical Communication’s International Standard (ISO excellence in annual reporting Australian and International 14001: 2004 Environmental from Australasian Reporting competitions Management Systems). Awards Inc. ASIC Summer School 2007 07–08 (program and directory) ASIC Annual Reports and Distinguished, Australia 2007 publications for companies Distinguished, International 2007 available from www.asic.gov.au or phone 1300 300 630 Your company and the law Excellence, Australia 2007 Consumer publications available Super decisions from www.fido.gov.au or phone Distinguished, Australia 2007 1300 300 630 Excellence, International 2007 CONTENTS CONTacT DETaiLS Letter of transmittal 01 How to find ASIC Visit us Melbourne: Level 24, ASIC at a glance www.asic.gov.au 03 120 Collins Street, Melbourne. Our key achievements 04 (For company registration, document lodgment, For consumers and investors searches and fees, visit the FIDO Centre, Chairman’s report 06 www.fido.gov.au Ground Floor, 120 Collins Street, Melbourne.) Financial summary 10 www.understandingmoney.gov.au Sydney: Level 18, 1 Martin Place, Sydney. Regulating during market turbulence 12 (For company registration, document lodgment, Major enforcement actions 14 How to contact ASIC searches and fees, visit Level 8, City Centre Tower, 55 Market Street, Sydney.) Consumers and retail investors 16 Email us at [email protected] Adelaide: Level 8, Allianz Centre, Capital market integrity 20 Phone us on 1300 300 630 • To report misconduct in financial markets, 100 Pirie Street, Adelaide. -

Contemporary Australian Corporate Law Stephen Bottomley , Kath Hall , Peta Spender , Beth Nosworthy Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-316-62827-0 — Contemporary Australian Corporate Law Stephen Bottomley , Kath Hall , Peta Spender , Beth Nosworthy Frontmatter More Information CONTEMPORARY AUSTRALIAN CORPORATE LAW Contemporary Australian Corporate Law provides an authoritative, contextual and critical analysis of Australian corporate and inancial markets law, designed to engage today’s LLB and JD students. Written by leading corporate law scholars, the text provides a number of fea- tures including: •a well-structured presentation of topics for Australian corporate law courses • consistent application of theory with discussion of corporate law principles (both theoretical and historical) •comprehensive discussion of case law with modern examples • integration of corporate law and corporate governance, all with clarity, insight and technical excellence. Central concepts are enhanced with dynamic and relevant discussions of corporate law in context, including debates relating to the role of corporations in society, the global convergence of corporate law, as well as corporations and human rights. Exploring the social, political and economic forces which shape modern cor- porations law, Contemporary Australian Corporate Law encourages a forward- thinking approach to understanding key concepts within the ield. Stephen Bottomley is Professor and Dean of the ANU College of Law at the Australian National University. Kath Hall is Associate Professor of the ANU College of Law at the Australian National University. Peta Spender is Professor and -

For Personal Use Only Use Personal For

22 May 2008 Company Announcements Australian Securities Exchange Level 4 20 Bridge Street SYDNEY NSW 2000 Company Secretary Wotif.com Holdings Limited Fax: (07) 3512 9914 Wotif.com Holdings Limited - Disclosures regarding shareholding interests We refer to the substantial holding notice given by Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (ANZ) on 12 May 2008, in connection with its interests in Wotif.com Holdings Limited. As disclosed in the substantial holding notice, ANZ has an interest in securities in Wotif.com Holdings Limited in which ING Australia Limited has a relevant interest, as a result of ANZ's voting power in ING Australia Limited exceeding 20%. ING Australia Limited and entities controlled by it have made some of those securities available to ANZ to be loaned out under ANZ's securities lending operations. The relevant securities were identified in the substantial holding notices previously provided by ANZ as comprising a separate parcel of securities in which ANZ had a relevant interest, thereby overstating ANZ's interests in Wotif.com Holdings Limited. We attach a revised substantial holding notice which replaces that provided by ANZ on 12 May 2008. As disclosed in the notice, ANZ's actual interest in Wotif.com Holdings Limited as at 27 March 2008 was 6.51%. As at 1 May 2008, ANZ's interest in Wotif.com Holdings Limited had not changed by more than 1%. As indicated in ANZ's announcement of 7 April 2008, ANZ has commenced a disposal programme (Disposal Programme) with respect to securities in which it has acquired an interest under Australian Master Securities Lending Agreements with Opes Prime Stockbroking Limited and Leveraged Capital Pty Ltd. -

ETO Listing Dates As at 11 March 2009

LISTING DATES OF CLASSES 03 February 1976 BHP Limited (Calls only) CSR Limited (Calls only) Western Mining Corporation (Calls only) 16 February 1976 Woodside Petroleum Limited (Delisted 29/5/85) (Calls only) 22 November 1976 Bougainville Copper Limited (Delisted 30/8/90) (Calls only) 23 January 1978 Bank N.S.W. (Westpac Banking Corp) (Calls only) Woolworths Limited (Delisted 23/03/79) (Calls only) 21 December 1978 C.R.A. Limited (Calls only) 26 September 1980 MIM Holdings Limited (Calls only) (Terminated on 24/06/03) 24 April 1981 Energy Resources of Aust Ltd (Delisted 27/11/86) (Calls only) 26 June 1981 Santos Limited (Calls only) 29 January 1982 Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (Calls only) 09 September 1982 BHP Limited (Puts only) 20 September 1982 Woodside Petroleum Limited (Delisted 29/5/85) (Puts only) 13 October 1982 Bougainville Copper Limited (Delisted 30/8/90) (Puts only) 22 October 1982 C.S.R. Limited (Puts only) 29 October 1982 MIM Holdings Limited (Puts only) Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Limited (Puts only) 05 November 1982 C.R.A. Limited (Puts only) 12 November 1982 Western Mining Corporation (Puts only) T:\REPORTSL\ETOLISTINGDATES Page 1. Westpac Banking Corporation (Puts only) 26 November 1982 Santos Limited (Puts only) Energy Resources of Aust Limited (Delisted 27/11/86) (Puts only) 17 December 1984 Elders IXL Limited (Changed name - Foster's Brewing Group Limited 6/12/90) 27 September 1985 Queensland Coal Trust (Changed name to QCT Resources Limited 21/6/89) 01 November 1985 National Australia -

Big Business in Twentieth-Century Australia

CENTRE FOR ECONOMIC HISTORY THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY SOURCE PAPER SERIES BIG BUSINESS IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AUSTRALIA DAVID MERRETT UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE SIMON VILLE UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG SOURCE PAPER NO. 21 APRIL 2016 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY ACTON ACT 0200 AUSTRALIA T 61 2 6125 3590 F 61 2 6125 5124 E [email protected] https://www.rse.anu.edu.au/research/centres-projects/centre-for-economic-history/ Big Business in Twentieth-Century Australia David Merrett and Simon Ville Business history has for the most part been dominated by the study of large firms. Household names, often with preserved archives, have had their company stories written by academics, journalists, and former senior employees. Broader national studies have analysed the role that big business has played in a country’s economic development. While sometimes this work has alleged oppressive anti-competitive behaviour, much has been written from a more positive perspective. Business historians, influenced by the pioneering work of Alfred Chandler, have implicated the ‘visible hand’ of large scale enterprise in national economic development particularly through their competitive strategies and modernised governance structures, which have facilitated innovation, the integration of national markets, and the growth of professional bureaucracies. While our understanding of the role of big business has been enriched by an aggregation of case studies, some writers have sought to study its impact through economy-wide lenses. This has typically involved constructing sets of the largest 100 or 200 companies at periodic benchmark years through the twentieth century, and then analysing their characteristics – such as their size, industrial location, growth strategies, and market share - and how they changed over time. -

The Review Class Actions in Australia

SECTION ONE The Review Class Actions in Australia 2015/2016 Contents 03 Introduction SECTION ONE 04 Headlines SECTION TWO 13 Multiple class actions SECTION THREE 17 Parties and players SECTION FOUR 20 Red hot – litigation funding in Australia SECTION FIVE 24 Settlements — the closing act SECTION SIX 29 Recent developments in class action procedure SECTION SEVEN 33 Global developments SECTION EIGHT 36 Outlook – what’s next for class actions in Australia? HIGH NUMBER CONSUMER OF ACTIONS CLASS ACTION THREAT STATE THIS YEAR OF Rise in ORIGIN consumer class actions Largest FY16 settlement 35 actions DePuy hip launched 8 replacement potentially up to in FY16 in FY15 35 class actions were $1.75 launched in FY16, BILLION 29 following a historic high of WERE IN Highest value 11 $250 claims filed in FY16 MILLION NSW 40 class actions launched the previous year 2 King & Wood Mallesons Introduction Welcome to our fifth annual report on class action practice in Australia, in which we consider significant judgments, events and developments between 1 July 2015 and 30 June 2016. It was another big year for new filings, with at least 35 new class actions commenced, of which 29 were filed in New South Wales. This is a similar level of new actions to last year (up from previous periods). 16 class actions settled (2014/15: 12), and more than an estimated $600 million has been approved in settlement funds. Looking deeper into the numbers, consumer claims have seized the spotlight in a number of ways: the biggest single settlement was the $250 million settlement of a consumer claim relating to DePuy International hip replacement products; the highest value claims filed are consumer actions in relation to the alleged use of defeat devices in vehicles, with one media report estimating the total value of the claim at $1.75 billion; and the bank fees class action against ANZ was a consumer class action that failed.