Spring- 2009-1-435-Iran.Mdi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ALAMAT PEJABAT JAWATAN DAN NAMA TELEFON/E-MEL

LEMBAGA HASIL DALAM NEGERI MALAYSIA DIREKTORI LHDNM ALAMAT PEJABAT JAWATAN DAN NAMA TELEFON/e-MEL KEDAH / PERLIS PEJABAT PENGARAH NEGERI PENGARAH T.T.: 04-7344100 SAMB.: 140000 LEVEL 6 & 7, MENARA BDB AMNAH BT. TAWIL e-mel: [email protected] 88, LEBUHRAYA DARULAMAN 05100 ALOR SETAR SETIAUSAHA SAMB.: 140001 KEDAH DARUL AMAN RUHAINAH BT. MUHAMAD TEL. AM : 04-7334100 PEGAWAI PERHUBUNGAN AWAM SAMB.: 140026 FAKS : 04-7334101 BALKHIS BT. ROSLI e-mel: [email protected] CAWANGAN ALOR SETAR PENGARAH T.T.: 04-7400280 SAMB.: 140111 WISMA HASIL, ROSIDE B. JANSI e-mel: [email protected] KOMPLEKS PENTADBIRAN KERAJAAN PERSEKUTUAN, BANDAR MUADZAM SHAH, SETIAUSAHA SAMB.: 140444 06550 ANAK BUKIT, AZLIZA BT. ZAINOL KEDAH DARUL AMAN TEL. AM : 04-7400100 TIMBALAN PENGARAH SAMB.: 140333 FAKS : 04-7329481 HAFSAH BT. MOHD NOOR e-mel: [email protected] PEGAWAI PERHUBUNGAN AWAM T.T.: 04-7400250 SAMB.: 140131 NURAZURA BT. MOHD YUSOF e-mel: [email protected] CAWANGAN SUNGAI PETANI PENGARAH T.T.: 04-4449720 SAMB.: 140600 MENARA HASIL NORAZIAH BT. AHMAD e-mel: [email protected] JALAN LENCONGAN TIMUR BANDAR AMAN JAYA 08000 SUNGAI PETANI, KEDAH SETIAUSAHA SAMB.: 140601 MASLINDA BT. MUKHTAR TEL. AM : 04-4456000 TIMBALAN PENGARAH T.T.: 04-4449730 SAMB.: 140673 WAN NOOR MAZUIN BT. WAN ARIS PEGAWAI PERHUBUNGAN AWAM T.T.: 04-4449772 SAMB.: 140726 NOOR FAZLLYZA BT. ZAKARIA e-mel: [email protected] [email protected] CAWANGAN SIASATAN ALOR SETAR PENGARAH T.T.: 04-7303987 SAMB.: 140501 ARAS 3, WISMA PERKESO MD. FAHMI BIN MD. SAID e-mel: [email protected] BANGUNAN MENARA ZAKAT JALAN TELOK WANJAH 05200 ALOR SETAR SETIAUSAHA SAMB.: 140504 KEDAH NORHAYATI BT. -

The Journal of Social Sciences Research ISSN(E): 2411-9458, ISSN(P): 2413-6670 Special Issue

The Journal of Social Sciences Research ISSN(e): 2411-9458, ISSN(p): 2413-6670 Special Issue. 6, pp: 735-738, 2018 Academic Research Publishing URL: https://arpgweb.com/journal/journal/7/special_issue Group DOI: https://doi.org/10.32861/jssr.spi6.735.738 Original Research Open Access The Challenges of Maintaining and Managing High Rise Buildings: Commercial Vs Residential Buildings M. S. Khalid* School of Government, Universiti Utara Malaysia, 06010 Sintok, Kedah, Malaysia A. H. Ahmad SSchool of Government, Universiti Utara Malaysia, 06010 Sintok, Kedah, Malaysia M. F. Sakdan School of Government, Universiti Utara Malaysia, 06010 Sintok, Kedah, Malaysia Abstract The issues of maintaining and managing high-rise buildings in Malaysia have been a matter for discussionfor a long time. This has led to significant amendments of the rules and regulations that have governed the stratified buildings in Malaysia. Now, the Strata Management Act 2013 (Strata Management Act 2013 Act 757), which came into force on June 1, 2015, is the main reference document that outlines the roles and responsibilities of the COB and JMB in the maintenance and management of high rise/stratified buildings. Act 757 recognised the formation of two main entities in terms of managing and maintaining the stratified buildings; these are the Commissioner of Building (COB) and the Joint Management Building (JMB) before the formation of the Management Corporation (MC). For the purposes of this article, the study focused solely on the MC of the commercial buildings perspective in Jitra, Kedah Malaysia because that particular building was only the commercial building to have been established by the MC. -

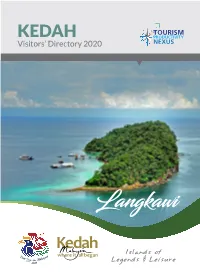

Visitors' Directory 2020

KEDAH Visitors’ Directory 2020 Islands of Legends & Leisure KEDAH Visitors’ Directory 2020 KEDAH Visitors’ Directory 2020 KEDAH 2 Where you’ll find more than meets the mind... SEKAPUR SIREH JUNJUNG 4 Chief Minister of Kedah SEKAPUR SIREH KEDAH Kedah State Secretary State Executive Councilor Where you’ll find Champion, Tourism Productivity Nexus 12 ABOUT TOURISM PRODUCTIVITY NEXUS (TPN) more than meets the mind... LANGKAWI ISLES OF LEGENDS & LEISURE 14 Map of Langkawi Air Hangat Village Lake of the Pregnant Maiden Atma Alam Batik Art Village Faizy Crystal Glass Blowing Studio Langkawi Craft Complex Eagle Square Langkawi Crocodile Farm CHOGM Park Langkawi Nature Park (Kilim Geoforest Park) Field of Burnt Rice Galeria Perdana Lagenda Park Oriental Village Buffalo Park Langkawi Rice Museum (Laman Padi) Makam Mahsuri (Mahsuri’s Tomb & Cultural Centre) Langkawi Wildlife Park Morac Adventure Park (Go-karting) Langkawi Cable Car Royal Langkawi Yacht Club KEDAH CUISINE AND A CUPPA 30 Food Trails Passes to the Pasars 36 LANGKAWI EXPERIENCES IN GREAT PACKAGES 43 COMPANY LISTINGS CONTENTS 46 ACCOMMODATION 52 ESSENTIAL INFORMATION No place in the world has a combination of This is Kedah, the oldest existing kingdom in Location & Transportation Getting Around these features: a tranquil tropical paradise Southeast Asia. Getting to Langkawi laced with idyllic islands and beaches framed Useful Contact Numbers by mystical hills and mountains, filled with Now Kedah invites the world to discover all Tips for Visitors natural and cultural wonders amidst vibrant her treasures from unique flora and fauna to Essential Malay Phrases You’ll Need in Malaysia Making Your Stay Nice - Local Etiquette and Advice cities or villages of verdant paddy fields, delicious dishes, from diverse experiences Malaysia at a Glance all cradled in a civilisation based on proven in local markets and museums to the history with archaeological site evidence coolest waterfalls and even crazy outdoor 62 KEDAH CALENDAR OF EVENTS 2020 going back three millennia in an ancient adventures. -

1970 Population Census of Peninsular Malaysia .02 Sample

1970 POPULATION CENSUS OF PENINSULAR MALAYSIA .02 SAMPLE - MASTER FILE DATA DOCUMENTATION AND CODEBOOK 1970 POPULATION CENSUS OF PENINSULAR MALAYSIA .02 SAMPLE - MASTER FILE CONTENTS Page TECHNICAL INFORMATION ON THE DATA TAPE 1 DESCRIPTION OF THE DATA FILE 2 INDEX OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 1: HOUSEHOLD RECORD 4 INDEX OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 2: PERSON RECORD (AGE BELOW 10) 5 INDEX OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 3: PERSON RECORD (AGE 10 AND ABOVE) 6 CODES AND DESCRIPTIONS OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 1 7 CODES AND DESCRIPTIONS OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 2 15 CODES AND DESCRIPTIONS OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 3 24 APPENDICES: A.1: Household Form for Peninsular Malaysia, Census of Malaysia, 1970 (Form 4) 33 A.2: Individual Form for Peninsular Malaysia, Census of Malaysia, 1970 (Form 5) 34 B.1: List of State and District Codes 35 B.2: List of Codes of Local Authority (Cities and Towns) Codes within States and Districts for States 38 B.3: "Cartographic Frames for Peninsular Malaysia District Statistics, 1947-1982" by P.P. Courtenay and Kate K.Y. Van (Maps of Adminsitrative district boundaries for all postwar censuses). 70 C: Place of Previous Residence Codes 94 D: 1970 Population Census Occupational Classification 97 E: 1970 Population Census Industrial Classification 104 F: Chinese Age Conversion Table 110 G: Educational Equivalents 111 H: R. Chander, D.A. Fernadez and D. Johnson. 1976. "Malaysia: The 1970 Population and Housing Census." Pp. 117-131 in Lee-Jay Cho (ed.) Introduction to Censuses of Asia and the Pacific, 1970-1974. Honolulu, Hawaii: East-West Population Institute. -

Sg. Petani - Taman No

No. Store Name Brief Location Store Address KD - Sg. Petani - Taman No. C-59 (GF) Jalan Permatang Gedong, 1 SP I Tmn Sejati Kdh Sejati Indah Taman Sejati Indah, 08000 Sg Petani, Kedah KD - Sg. Petani - Taman Ria No 164 (GF), Jalan Kelab Cinta Sayang, 2 SP II TmnRiaJaya Kdh Jaya Taman Ria Jaya, 08000 Sg Petani, Kedah KD - Sg. Petani - Taman No 99A, P-K-P Jalan Pengkalan, Taman 3 SPIIITmnPknBaruSPKdh Pekan Baru Pekan Baru, 08000 Sg Petani, Kedah KD - Alor Setar - Pekan No. 114 Jalan PSK 4, Pekan Simpang Kuala, 4 Spg Kuala A.Star Kdh Simpang Kuala 05400 Alor Setar, Kedah KD - Kulim - Taman No 39 (GF), Lorong Kemuning 1, Taman 5 Kemuning Kulim Kdh Kemuning Kemuning, 09000 Kulim, Kedah No. 161 (GF), Jalan Putra, 05100 Alor Setar, 6 Jln Putra A Star Kdh KD - Alor Setar - Jalan Putra Kedah KD - Jitra - Bandar Darulaman No 48 (GF), Jalan Pantai Halban, Bandar 7 BdrDarulamanJitraKdh Jaya Darulaman Jaya, 06000 Jitra, Kedah No. K 177, Jalan Sultanah Sambungan 8 Wira Mergong Kdh KD - Taman Wira Mergong Taman Wira Mergong, 05250 Kedah No 182 (GF) Jalan Lagenda Heights 1, KD - Sg. Petani - Lagenda 9 LagendaHeightsSP KDH Lagenda Heights 08000 Sungai Petani, Heights Kedah KD - Alor Setar - Taman No. 5009 (GF), Jalan Tun Razak, Taman 10 PKNK, Alor Setar Kdh PKNK - Jalan Tun Razak PKNK, 05200 Alor Setar, Kedah KD - Alor Setar - Komplek Lot 81 (GF), Kompleks Perniagaan Sultan 11 Kompleks PSAH AS Kdh Perniagaan Sultan Abdul Abdul Hamid, Persiaran Sultan Abdul Hamid, Hamid 05000 Alor Setar, Kedah KD - Alor Setar - Jalan Tun No. -

The Siamese in Kedah Under Nation-State Making

The Siamese in Kedah under nation-state making Keiko Kuroda (Kagoshima University) 1: Historical Background Kedah have ever been one of the tributary states of Siam. Siam had the tributary states in the Malay Peninsula until 1909. These tributary states were Malay Sultanate states that became Islamized in the 15th century. However, Ayutthaya, the Court of Siam, have kept the tributary relations with them, sometime with military force. Because these Malay states were important and indispensable port polities for Ayutthaya's trade network. Anglo-Siam Treaty of 1909 made the modern border between Siam and British Malaya. Satun, which was a part of Kedah, and Patani remained in Siam. And Kedah and others were belonging to British Malaya. This border was the result of political struggle between Government of Siam and British Malaya. However, Kedah had controlled wider area before this. The area spread over archipelago along the western coast of Peninsula near the Phuket Island. And Kedah had the characteristics that were different from other Siam tributary states on the eastern coast. In Kedah, many people could understand and speak Thai Language. The Influence of Thai was left well for the name of the places and the traditional entertainments as well. Then, there are people who speak Thai as vernacular at present. These Thai-speakers are " the Samsams " who are Malay Muslims, and the Siamese who are Thai Theravada Buddhists. In this paper, I attempt to reconstruct the historical experiences of the Siamese of Kedah from 19th century to present. The source of the paper is from the documents in the National Archives of Malaysia and data from my fieldwork in Kedah in 1990's. -

Suruhanjaya Pilihan Raya Malaysia Negeri : Kedah

SURUHANJAYA PILIHAN RAYA MALAYSIA SENARAI BILANGAN PEMILIH MENGIKUT DAERAH MENGUNDI SEBELUM PERSEMPADANAN 2016 NEGERI : KEDAH SENARAI BILANGAN PEMILIH MENGIKUT DAERAH MENGUNDI SEBELUM PERSEMPADANAN 2016 NEGERI : KEDAH BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA PERSEKUTUAN : LANGKAWI BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NEGERI : AYER HANGAT KOD BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NEGERI : 004/01 SENARAI DAERAH MENGUNDI DAERAH MENGUNDI BILANGAN PEMILIH 004/01/01 KUALA TERIANG 1,370 004/01/02 EWA 1,416 004/01/03 PADANG LALANG 2,814 004/01/04 KILIM 1,015 004/01/05 LADANG SUNGAI RAYA 1,560 004/01/06 WANG TOK RENDONG 733 004/01/07 BENDANG BARU 1,036 004/01/08 ULU MELAKA 1,642 004/01/09 NYIOR CHABANG 1,436 004/01/10 PADANG KANDANG 1,869 004/01/11 PADANG MATSIRAT 621 004/01/12 KAMPUNG ATAS 1,205 004/01/13 BUKIT KEMBOJA 2,033 004/01/14 MAKAM MAHSURI 1,178 JUMLAH PEMILIH 19,928 SENARAI BILANGAN PEMILIH MENGIKUT DAERAH MENGUNDI SEBELUM PERSEMPADANAN 2016 NEGERI : KEDAH BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA PERSEKUTUAN : LANGKAWI BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NEGERI : KUAH KOD BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NEGERI : 004/02 SENARAI DAERAH MENGUNDI DAERAH MENGUNDI BILANGAN PEMILIH 004/02/01 KAMPUNG GELAM 1,024 004/02/02 KEDAWANG 1,146 004/02/03 PANTAI CHENANG 1,399 004/02/04 TEMONYONG 1,078 004/02/05 KAMPUNG BAYAS 1,077 004/02/06 SUNGAI MENGHULU 2,180 004/02/07 KELIBANG 2,042 004/02/08 DUNDONG 1,770 004/02/09 PULAU DAYANG BUNTING 358 004/02/10 LUBOK CHEMPEDAK 434 004/02/11 KAMPUNG TUBA 1,013 004/02/12 KUAH 2,583 004/02/13 KAMPUNG BUKIT MALUT 1,613 JUMLAH PEMILIH 17,717 SENARAI BILANGAN PEMILIH MENGIKUT DAERAH MENGUNDI SEBELUM PERSEMPADANAN -

Sintok International Conference on Social Science and Management (Siconsem 2017)

SINTOK INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON SOCIAL SCIENCE AND MANAGEMENT (SICONSEM 2017) 4-5 DECEMBER 2017 ADYA HOTEL, LANGKAWI, MALAYSIA SINTOK INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON SOCIAL SCIENCE AND MANAGEMENT (SICONSEM 2017) 4-5 DECEMBER 2017 ADYA HOTEL, LANGKAWI, MALAYSIA ORGANISED BY: UUM PRESS UNIVERSITI UTARA MALAYSIA http://www.siconsem.uum.edu.my http://www.uumpress.uum.edu.my PENERBIT UNIVERSITI UTARA MALAYSIA Sintok • 2017 eISBN 978-967-2064-65-7 Editors Dr. Zamimah Osman Nor Arpizah Atan Nor Aziani Jamil Graphic and Layout Zuraizee Zulkifli Mohammad Hazim Abdul Azis Copyright © 2017 UUM Press. All Rights reserved. Published by UUM Press This work is subject to copyright. All right are reserved. Whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the right of translating, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on papers, electronics or any other way, and storage in data banks without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate fees as charged by the Publisher. Due care has been taken to ensure that the information provided in this proceeding is correct. However, the publisher bears no responsibility for any damage resulting from any inadvertent omission or inaccuracy of the content in the proceedings. This proceeding is published in electronic format. Printed by: UUM Press ORGANIZING COMMITTEE Advisor Professor Dato’ Seri Dr. Mohamed Mustafa Ishak (Vice-Chancellor, Universiti Utara Malaysia) Conference Director Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ram Al Jaffri Saad Assisstant Conference Director Prof. Dr. Rosna Awang Hashim Panel of Experts Prof. Dr. Rosna Awang Hashim (Editor-in-Chief, Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction) Prof. -

AIMST Newsletter

AIMST Newsletter (AIMST) Asian Institute of Medicine, Science and Technology This Newsletter is Intended for AIMST University’s Community and its Stakeholders VolumeVolume 1,2, Issue Issue 4 4 January−March 2020 12th Convocation Ceremony - Highlights Convocation is among the biggest exciting events held on the AIMST University’s lush green Campus. The great enthusiasm of the graduands, their parents, friends and family members, and the presence of specially invited guests, local and international col- laborators as well as members of AIMST University management and dynamic teaching staff, makes it unique. ►Read more on page 3. Proactive Measures to Prevent COVID-19 Occurrence at AIMST University AIMST University’s Senior Management Team is meeting on a regular basis to carefully review the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic situation in order to ensure that all necessary steps are taken proactively for the safety of COVID-19 students, staff and stakeholder. The university management team will continue to monitor COVID-19 pandemic developments both domestically and abroad and will notify the critical updates as appropriate to the AIMST community. For efficient communication, AIMST University has launched a website (https://www.aimst.edu.my/event-news/covid-19/), which will serve as a resource for its community. Students, staff, and stakeholders are advised to visit the above-stated website to monitor the situation and stay updated for safety.◼ Published by: AIMST Sdn. Bhd (496741-P), Semeling, 08100 Bedong, Kedah Darul Aman, Malaysia. Printed by: 2K Label Printing Sdn. Bhd., No.100L, Kawasan Perindustrian Mergong, 05150 Alor Setar, Kedah. KDN Permit: PP19484/06/2019 (035083); ISSN: 2682-874X; www.aimst.edu.my AIMST Newsletter Volume 2, Issue 4 Editorial Board Contents Editor-in-Chief: Subhash J Bhore • 12th Convocation Ceremony – Highlights………………………………………..................... -

Visitors' Directory 2020

KEDAH Visitors’ Directory 2020 Wealth of Paddy & Tranquility KEDAH Visitors’ Directory 2020 KEDAH Visitors’ Directory 2020 KEDAH 2 Where you’ll find more than meets the mind... SEKAPUR SIREH JUNJUNG 4 Chief Minister of Kedah SEKAPUR SIREH KEDAH Kedah State Secretary State Executive Councilor Where you’ll find Champion, Tourism Productivity Nexus ABOUT TOURISM PRODUCTIVITY NEXUS (TPN) 12 more than meets the mind... WELCOME TO PENDANG 14 Map of Pendang PENDANG ATTRACTIONS 16 Bazaar Melayu Kemboja Pendang Pendang Lake Pendang Waterfront Sungai Rambai Forest Reserve Bendang Bukit Raya (Sunset View) Bukit Perak Recreational Forest Jelapang Padi Pondok Hampar Telaga Gajah (Elephant Well) Wat Siam Chindaram / Wat Thanara Tobiar Gold Mango Farm KEDAH CUISINE AND A CUPPA 22 Food Trails 25 COMPANY LISTINGS 26 ACCOMMODATION ESSENTIAL INFORMATION 28 Location & Transportation Getting Around Getting to Langkawi Useful Contact Numbers Tips for Visitors Essential Malay Phrases You’ll Need in Malaysia Making Your Stay Nice - Local Etiquette and Advice Malaysia at a Glance CONTENTS 38 KEDAH CALENDAR OF EVENTS 2020 No place in the world has a combination of This is Kedah, the oldest existing kingdom in 40 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT these features: a tranquil tropical paradise Southeast Asia. EMERGENCIES laced with idyllic islands and beaches framed 42 by mystical hills and mountains, filled with Now Kedah invites the world to discover all 43 MPC OFFICES natural and cultural wonders amidst vibrant her treasures from unique flora and fauna to cities or villages of verdant paddy fields, delicious dishes, from diverse experiences all cradled in a civilisation based on proven in local markets and museums to the history with archaeological site evidence coolest waterfalls and even crazy outdoor going back three millennia in an ancient adventures. -

Knowledge Management

TIMO Model As The Basis For K-Workers: A Case Study On Pusat Komuniti Siber, Jitra Ariffin Abdul Mutaliba, Ezanee Hj Mohamed Eliasb and Jasni Ahmada aFaculty of Information Technology, Universiti Utara Malaysia, 06010 Sintok, Kedah Tel: 04-9284611, Fax: 04-9284753 E-mail:[email protected], [email protected] bFaculty Management of Technology, Universiti Utara Malaysia, 06010 Sintok, Kedah Tel: 04-9284792, Fax: 04-9284753, E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT of information for specific purposes. The Today it is widely recognized that Information traditional discipline of IS is presently and Communication Technology (ICT) is undergoing a major evolutionary step into essential for society, government and commerce societal applications. These evolutionary have in economic, social, educational, and cultural. In changed from time to time started from line with the aspirations of Vision 2020, the ICT electronic data processing (EDP) in late 1960- functions have envisioned the evolution of a 1970 to Community Informatics (CI) in year value-based knowledge society in the Malaysian 2000 onward (Harris, R., 2002). He has proposed mole, where its society is rich in information, a discussion framework for the emergence of CI empowered by knowledge, infused with a (table 1). The term CI refers to an emerging area distinctive value-system, and is self-governing. of research and practice, focusing in the use of Government and private agencies have Information Technology (IT) by human recognized the growing issues associated with communities. inequitable ICT access and have provided funded programs have failed to deliver on their IT can be defined as the technological desired aims and that the societal and components of an information system or community based disadvantages. -

Resource-Use and Allocative Efficiency of Paddy Rice Production in Mada, Malaysia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1700 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2855 (Online) Vol.7, No.1, 2016 Resource-Use and Allocative Efficiency of Paddy Rice Production in Mada, Malaysia Abiola, Olapeju Adedoyin 1 Mad Nasir Shamsudin 1* Alias Radam 2 Ismail Abd Latif 1 1. Department of Agribusiness and information system 2. Department of Management and Marketing, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Malaysia Abstract The study examined resource-use and allocative efficiency of paddy rice production in the MADA, Malaysia. A total sampling size of 396 rice farmers were selected using a multistage random sampling through a well- structured questionnaire. The independent samples F-tests, Ordinary Least Square analyses techniques, descriptive statistics, Gross margin analysis and Cobb-Douglas production function analysis that combines the conventional neoclassical test of economic and technical efficiencies was employed in the study. Findings revealed that all inputs used were positively significant. Rice production was found to be profitable as farmers realized RM2,054.03 per ha as Gross Margin in the study area. Result of the allocative efficiency of inputs confirmed that rice producers in the area did not attain optimal allocative efficiency, seed input (0.29) had the highest allocative efficiency while fertilizer input (0.06) showed the least allocative efficient input. The findings of the study emphasized the need to improve farm efficiency at all levels. It is therefore, recommend that the rice farmers be encouraged to use their inputs up to the point the values of the marginal products (MVPs) equates their factor prices (i.e.