Comic Book Princesses for Grown-Ups: Cinderella Meets The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fairest: Cinderella - of Men and Mice Volume 4 Pdf

FREE FAIREST: CINDERELLA - OF MEN AND MICE VOLUME 4 PDF Shawn McManus,Marc Andreyko,Bill Willingham | 144 pages | 14 Oct 2014 | DC Comics | 9781401250058 | English | United States Fairest: Of Men and Mice #1 - Volume 4 (Issue) Uh-oh, it looks like your Internet Explorer is out of date. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. Javascript is not enabled in your browser. Enabling JavaScript in your browser will allow you to experience all the features of our site. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. NOOK Book. Home 1 Books 2. Add to Wishlist. Sign in to Purchase Instantly. Explore Now. Buy As Gift. Fairest: Cinderella - Of Men and Mice Volume 4 Cinderella returns in an all-new epic! After an assassination attempt on Snow White, Cind is called back into service to unravel an age-old conspiracy that dates back to that fateful midnight ball! Can Cind uncover the plot and prevent a massacre in Fabletown? Collects issues Product Details About the Author. He co-created with artist Jesus Saiz Kate Spencer, the title character of the series, the first female character to carry the long-running legacy. Related Searches. What was What was hidden in the paintings and why? A mystery that dates back almost a century is solved, but the danger has never been greater. View Product. Nocturna is out of Arkham, but is she really fit to return to society? The cultish crimes continue to corrupt Gotham City - and their next target is Also, Batwoman's toxic connection to Nocturna continues to spiral down to a place where even demons fear to tread! Batwoman Vol. -

Chinese Fables and Folk Stories

.s;^ '^ "It--::;'*-' =^-^^^H > STC) yi^n^rnit-^,; ^r^-'-,. i-^*:;- ;v^ r:| '|r rra!rg; iiHSZuBs.;:^::^: >» y>| «^ Tif" ^..^..,... Jj AMERICMJ V:B00lt> eOMI^^NY"' ;y:»T:ii;TOiriai5ia5ty..>:y:uy4»r^x<aiiua^^ nu,S i ;:;ti! !fii!i i! !!ir:i!;^ | iM,,TOwnt;;ar NY PUBLIC LIBRARY THE BRANCH LIBRARIES 3 3333 08102 9908 G258034 Digitized by the Internet Arciiive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/chinesefablesfolOOdavi CHINESE FABLES AND FOLK STORIES MARY HAYES DAVIS AND CHOW-LEUNG WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY YIN-CHWANG WANG TSEN-ZAN NEW YORK •:• CINCINNATI •: CHICAGO AMERICAN BOOKCOMPANY Copyright, 1908, by AMERICAN BOOK COMPANY Entered at Stationers' Hall, London Copyright, 1908, Tokyo Chinese Fables W. p. 13 y\9^^ PROPERTY OF THE ^ CITY OF MW YOBK G^X£y:>^c^ TO MY FRIEND MARY F. NIXON-ROULET PREFACE It requires much study of the Oriental mind to catch even brief glimpses of the secret of its mysterious charm. An open mind and the wisdom of great sympathy are conditions essential to making it at all possible. Contemplative, gentle, and metaphysical in their habit of thought, the Chinese have reflected profoundly and worked out many riddles of the universe in ways peculiarly their own. Realization of the value and need to us of a more definite knowledge of the mental processes of our Oriental brothers, increases wonder- fully as one begins to comprehend the richness, depth, and beauty of their thought, ripened as it is by the hidden processes of evolution throughout the ages. To obtain literal translations from the mental store- house of the Chinese has not been found easy of accom- plishment; but it is a more difficult, and a most elusive task to attempt to translate their fancies, to see life itself as it appears from the Chinese point of view, and to retell these impressions without losing quite all of their color and charm. -

Maleficent's Character Development As Seen In

MALEFICENT’S CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT AS SEEN IN MALEFICENT MOVIE A GRADUATING PAPER Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Gaining The Bachelor Degree in English Literature By : Nur Asmawati 10150043 ENGLISH DEPARTEMENT FACULTY OF ADAB AND CULTURAL SCIENCES STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY SUNAN KALIJAGA YOGYAKARTA 2015 PERUBAHAN KARAKTER MALEFICENT SEPERTI YANG TERGAMBAR DALAM FILM MALEFICENT Oleh Nur Asmawati ABSTRAK Skripsi ini berjudul “Perubahan Karakter Maleficent dalam Film Maleficent”. Maleficent adalah karakter utama dalam film Maleficent karya Joe Roth. Movie ini menarik untuk di analisis karakter utama Maleficent tersebut mengalami perubahan dari seorang peri yang baik menjadi peri yang jahat. Perubahan ini disebabkan oleh cintanya pada manusia bernama Stefan dan kemudian dan mendapat penghianatan. Data yang diambil dari film untuk analisis ini adalah naskah film tersebut. Metode analisis data merupakan penelitian deskriptif kualitatif. Penulis menggunakan teori struktural khususnya teori perubahan karakter, teori tersebut berhubungan dengan gagasan perubahan karakter yang di usulkan oleh William Kenny. Kesimpulan dari penelitian ini adalah Maleficent sebagai tokoh utama dalam film Maleficent mengalami perubahan karakter. Dalam cerita, Maleficent mengalami dua perubahan karakter yaitu, pertama karakter baik berubah menjadi karakter buruk, dan buruk karakter menjadi baik. Dalam perubahan karakter dari baik menjadi buruk disebabkan oleh dari berjiwa kepemimpinan dan persahabatan dan memiliki dendam dan dari mempunyai rasa cinta dan mengasihani menjadi marah dan benci. Sedangakan perubahan karakter dari buruk menjadi baik hanya karena dari rasa benci dan marah menjadi cinta dan menjadi kasihan Kata Kunci : Tokoh, Film, Perubahan Karakter. iii MALEFICENT’S CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT AS SEEN IN MALEFICENT MOVIE By Nur Asmawati ABSTRACT This graduating paper is entitled “Maleficent’s Character Development as Seen in Maleficent Movie”. -

A Theology of Creation Lived out in Christian Hymnody

Concordia Seminary - Saint Louis Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Concordia Seminary Scholarship 5-1-2014 A Theology of Creation Lived Out in Christian Hymnody Beth Hoeltke Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.csl.edu/phd Part of the Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Hoeltke, Beth, "A Theology of Creation Lived Out in Christian Hymnody" (2014). Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation. 58. https://scholar.csl.edu/phd/58 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Concordia Seminary Scholarship at Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A THEOLOGY OF CREATION LIVED OUT IN CHRISTIAN HYMNODY A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, Department of Doctrinal Theology in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Beth June Hoeltke May 2014 Approved by Dr. Charles Arand Advisor Dr. Kent Burreson Reader Dr. Erik Herrmann Reader © 2014 by Beth June Hoeltke. All rights reserved. Dedicated in loving memory of my parents William and June Hoeltke Life is Precious. Give it over to God, our Creator, and trust in Him alone. CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS -

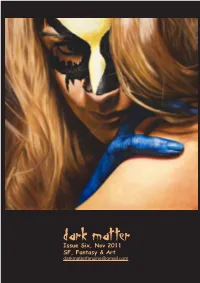

Dark Matter #6

Cover: Wolverine by JKB Fletcher DarkIssue Six, Matter Nov 2011 SF, Fantasy & Art [email protected] Dark Matter Contents: Issue 6 Cover: Wolverine by JKB Fletcher 1 Donations 6 Via Paypal 6 About Dark Matter 7 Competitions 8 Winners 8 Competition terms and conditions 8 Ambassador’s Mission - autographed copy 9 Blood Song - autographed copy 9 Passion - autographed copy 9 The Creature Court Fashion Challenge Contest 10 Christmas Parade 11 Visionary Project 13 Convention/Expo reports 14 Tights and Tiaras: Female Superheroes and Media Cultures 14 #thevenue 14 #thefood 14 #thesessions 15 #karenhealy 15 #fairytaleheroineorfablesuperspy 16 #princecharmingbydaysuperheroinebynight 16 #supermom 16 #wonderwomanworepants 17 #wonderwomanforaday 17 #mywonderwoman 17 #motivationtofight 18 #thefemalesuperhero 19 #dinner 19 #xenaandbuffy 20 #thestakeisnotthepower 20 #buffythetransmediahero 20 #artistandauthors 21 #biggernakedbreasts 22 #sistersaredoingit 22 #sugarandspice 23 #jeangreyasphoenix 23 #nakedmystique 24 #theend 25 Armageddon Expo 2011 26 #thelonegunmen 27 2 Dark Matter #doctorwho 31 #cyberangel 33 #bestlaidplans 33 #theguild 34 #sylvestermccoy 36 #wrapup 37 Timeline Festival 40 MelbourneZombieShuffle 46 White Noise 51 Success without honour 51 New Directions 52 Interviews 54 Troopertrek 2011 54 #update 58 #links 58 Sandeep Parikh and Jeff Lewis @ Armageddon 59 #Effinfunny 60 #5minutecomedyhour 61 #theguild 63 #stanlee 67 #neilgaiman 68 #eringray 69 #zabooandcodex 70 #theguildcomics 72 #thefuture 73 JKB Fletcher talks to Dark Matter -

(Mr) 3,60 € Aug18 0015 Citize

Συνδρομές και Προπαραγγελίες Comics Αύγουστος 2018 (για Οκτώβριο- Nοέμβριο 2018) Μέχρι τις 17 Αυγούστο, στείλτε μας email στο [email protected] με θέμα "Προπαραγγελίες Comics Αύγουστος 2018": Ονοματεπώνυμο Username Διεύθυνση, Πόλη, ΤΚ Κινήτο τηλέφωνο Ποσότητα - Κωδικό - Όνομα Προϊόντος IMAGE COMICS AUG18 0013 BLACKBIRD #1 CVR A BARTEL 3,60 € AUG18 0014 BLACKBIRD #1 CVR B STAPLES (MR) 3,60 € AUG18 0015 CITIZEN JACK TP (APR160796) (MR) 13,49 € AUG18 0016 MOTOR CRUSH TP VOL 01 (MAR170820) 8,49 € AUG18 0017 MOTOR CRUSH TP VOL 02 (MAR180718) 15,49 € AUG18 0018 DEAD RABBIT #1 CVR A MCCREA (MR) 3,60 € AUG18 0020 INFINITE HORIZON TP (FEB120448) 16,49 € AUG18 0021 LAST CHRISTMAS HC (SEP130533) 22,49 € AUG18 0022 MYTHIC TP VOL 01 (MAR160637) (MR) 15,49 € AUG18 0023 ERRAND BOYS #1 (OF 5) CVR A KOUTSIS 3,60 € AUG18 0024 ERRAND BOYS #1 (OF 5) CVR B LARSEN 3,60 € AUG18 0025 POPGUN GN VOL 01 (NEW PTG) (SEP071958) 26,99 € AUG18 0026 POPGUN GN VOL 02 (MAY082176) 26,99 € AUG18 0027 POPGUN GN VOL 03 (JAN092368) 26,99 € AUG18 0028 POPGUN GN VOL 04 (DEC090379) 26,99 € AUG18 0029 EXORSISTERS #1 CVR A LAGACE 3,60 € AUG18 0030 EXORSISTERS #1 CVR B GUERRA 3,60 € AUG18 0033 DANGER CLUB TP VOL 01 (SEP120436) 8,49 € AUG18 0034 DANGER CLUB TP VOL 02 REBIRTH (APR150581) 8,49 € AUG18 0035 PLUTONA TP (MAR160642) 15,49 € AUG18 0036 INFINITE DARK #1 3,60 € AUG18 0037 HADRIANS WALL TP (JUN170665) (MR) 17,99 € AUG18 0038 WARFRAME TP VOL 01 (O/A) 17,99 € AUG18 0039 JOOK JOINT #1 (OF 5) CVR A MARTINEZ (MR) 3,60 € AUG18 0040 JOOK JOINT #1 (OF 5) CVR B HAWTHORNE (MR) 3,60 -

Super Satan: Milton’S Devil in Contemporary Comics

Super Satan: Milton’s Devil in Contemporary Comics By Shereen Siwpersad A Thesis Submitted to Leiden University, Leiden, the Netherlands in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MA English Literary Studies July, 2014, Leiden, the Netherlands First Reader: Dr. J.F.D. van Dijkhuizen Second Reader: Dr. E.J. van Leeuwen Date: 1 July 2014 Table of Contents Introduction …………………………………………………………………………... 1 - 5 1. Milton’s Satan as the modern superhero in comics ……………………………….. 6 1.1 The conventions of mission, powers and identity ………………………... 6 1.2 The history of the modern superhero ……………………………………... 7 1.3 Religion and the Miltonic Satan in comics ……………………………….. 8 1.4 Mission, powers and identity in Steve Orlando’s Paradise Lost …………. 8 - 12 1.5 Authority, defiance and the Miltonic Satan in comics …………………… 12 - 15 1.6 The human Satan in comics ……………………………………………… 15 - 17 2. Ambiguous representations of Milton’s Satan in Steve Orlando’s Paradise Lost ... 18 2.1 Visual representations of the heroic Satan ……………………………….. 18 - 20 2.2 Symbolic colors and black gutters ……………………………………….. 20 - 23 2.3 Orlando’s representation of the meteor simile …………………………… 23 2.4 Ambiguous linguistic representations of Satan …………………………... 24 - 25 2.5 Ambiguity and discrepancy between linguistic and visual codes ………... 25 - 26 3. Lucifer Morningstar: Obedience, authority and nihilism …………………………. 27 3.1 Lucifer’s rejection of authority ………………………..…………………. 27 - 32 3.2 The absence of a theodicy ………………………………………………... 32 - 35 3.3 Carey’s flawed and amoral God ………………………………………….. 35 - 36 3.4 The implications of existential and metaphysical nihilism ……………….. 36 - 41 Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………………. 42 - 46 Appendix ……………………………………………………………………………… 47 Figure 1.1 ……………………………………………………………………… 47 Figure 1.2 ……………………………………………………………………… 48 Figure 1.3 ……………………………………………………………………… 48 Figure 1.4 ………………………………………………………………………. -

Bill Willingham's Fables—A Fairy-Tale Epic

humanities Article We All Live in Fabletown: Bill Willingham’s Fables—A Fairy-Tale Epic for the 21st Century Jason Marc Harris Department of English, Texas A&M University, MS 4227 TAMU, College Station, TX 77843, USA; [email protected]; Tel.: +1-979-845-8358 Academic Editor: Claudia Schwabe Received: 1 March 2016; Accepted: 9 May 2016; Published: 19 May 2016 Abstract: Bill Willingham’s Fables comic book series and its spin-offs have spanned fourteen years and reinforce that fairy-tale characters are culturally meaningful, adaptable, subversive, and pervasive. Willingham uses fairy-tale pastiche and syncreticism based on the ethos of comic book crossovers in his redeployment of previous approaches to fairy-tale characters. Fables characters are richer for every perspective that Willingham deploys, from the Brothers Grimm to Disneyesque aesthetics and more erotic, violent, and horrific incarnations. Willingham’s approach to these fairy-tale narratives is synthetic, idiosyncratic, and libertarian. This tension between Willingham’s subordination of fairy-tale characters to his overarching libertarian ideological narrative and the traditional folkloric identities drives the storytelling momentum of the Fables universe. Willingham’s portrayal of Bigby (the Big Bad Wolf turned private eye), Snow White (“Fairest of Them All”, Director of Operations of Fabletown, and avenger against pedophilic dwarves), Rose Red (Snow’s divergent, wild, and jealous sister), and Jack (narcissistic trickster) challenges contemporary assumptions about gender, heroism, narrative genres, and the very conception of a fairy tale. Emerging from negotiations with tradition and innovation are fairy-tale characters who defy constraints of folk and storybook narrative, mythology, and metafiction. -

Magazines V17N9.Qxd

Apr COF C1:Customer 3/8/2012 3:24 PM Page 1 ORDERS DUE th 18APR 2012 APR E E COMIC H H T T SHOP’S CATALOG IFC Darkhorse Drusilla:Layout 1 3/8/2012 12:24 PM Page 1 COF Gem Page April:gem page v18n1.qxd 3/8/2012 11:16 AM Page 1 THE MASSIVE #1 STAR WARS: KNIGHT DARK HORSE COMICS ERRANT— ESCAPE #1 (OF 5) DARK HORSE COMICS BEFORE WATCHMEN: MINUTEMEN #1 DC COMICS MARS ATTACKS #1 IDW PUBLISHING AMERICAN VAMPIRE: LORD OF NIGHTMARES #1 DC COMICS / VERTIGO PLANETOID #1 IMAGE COMICS SPAWN #220 SPIDER-MEN #1 IMAGE COMICS MARVEL COMICS COF FI page:FI 3/8/2012 11:40 AM Page 1 FEATURED ITEMS COMICS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Strawberry Shortcake Volume 2 #1 G APE ENTERTAINMENT The Art of Betty and Veronica HC G ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Bleeding Cool Magazine #0 G BLEEDING COOL 1 Radioactive Man: The Radioactive Repository HC G BONGO COMICS Prophecy #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Pantha #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 Power Rangers Super Samurai Volume 1: Memory Short G NBM/PAPERCUTZ Bad Medicine #1 G ONI PRESS Atomic Robo and the Flying She-Devils of the Pacific #1 G RED 5 COMICS Alien: The Illustrated Story Artist‘s Edition HC G TITAN BOOKS Alien: The Illustrated Story TP G TITAN BOOKS The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen III: Century #3: 2009 G TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Harbinger #1 G VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC Winx Club Volume 1 GN G VIZ MEDIA BOOKS & MAGAZINES Flesk Prime HC G ART BOOKS DC Chess Figurine Collection Magazine Special #1: Batman and The Joker G COMICS Amazing Spider-Man Kit G COMICS Superman: The High Flying History of America‘s Most Enduring -

On Jack's Revisions and Transfictional Crossing from Fables To

Second-degree Rewriting Strategies: On Jack’s Revisions and Transfictional Crossing from Fables to Jack of Fables Christophe Dony Introduction Bill Willingham, Mark Buckingham, et al.’s Vertigo series Fables (2002-2015), as its name suggests, revolves around the present-day lives of known fables, legends, and folk- and fairytale characters such as Snow White, Mowgli, Cinderella, and the Big Bad Wolf (Bigby) after they have been forced to leave their magical “native” fairytale homelands. As a result of their forced migration, these folk- and fairytale characters—who are referred to as Fables in the series—have found refuge in “our reality,” in which they have established a New York stronghold. This refugee facility of sorts for fictional characters is known as Fabletown; it is magically protected and concealed from humans who are, consequently, unable to detect the presence of Fables in the “real world.” This process of re-narrativization1 governing Fables, i.e. how known characters and their attendant storyworlds are re-configured in a new narrative, goes hand in hand with genre- meshing practices. Fables’ characters are articulated in other “pulpy” genres and settings than those they are generally associated with, i.e. the fairytale and the marvelous. As comics critic and narratologist Karin Kukkonen explains at length in her examination of comics storytelling strategies (see Kukkonen, Contemporary Comics Storytelling 74-86), Fables meshes fairytale traditions and narratives with, for example, noir/detective fiction in the first story arc “Legends in Exile” (Fables #1-5), and with the political fable/thriller canvas of George Orwell’s Animal Farm in the series’ eponymous story arc (Fables # 6-10). -

Sleeping Beauty’

The Character Alteration of Maleficent from ‘Sleeping Beauty’ into ‘Maleficent’ Movie Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Humaniora in English and Literature Department of Faculty of Adab and Humanities of UIN Alauddin Makassar By: NUR HALIDASIA 40300111091 ENGLISH AND LITERATURE DEPARTMENT ADAB AND HUMANITIES FACULTY ALAUDDIN STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY OF MAKASSAR 2016 PERNYATAAN KEASLIAN SKRIPSI Dengan penuh kesadaran, penulis yang bertanda tangan dibawah ini menyatakan bahwa skripsi ini benar adalah hasil karya penulis sendiri, dan jika di kemudian hari terbukti merupakan duplikat, tiruan, plagiat, atau dibuat oleh orang lain secara keseluruhan ataupun sebagian, maka skripsi ini dan gelar yang diperoleh batal demi hukum. Samata, 04 November 2016 Penulis Nur Halidasia 40300111091 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENT Alhamdulillahirabbil’aalamin, the writer praises to Allah SWT for His blessing, love, opportunity, health, and mercy, thus the writer can complete this thesis. Next, Shalawat are addressed to our prophet Muhammad SAW, for his model and guidance in the life. The writer realizes that there are many people who give their support, prayer and encouragement sincerely to help the writer completing this thesis. For those reason, the writer would like to express her deepest gratitude to the following: 1. The writer’s beloved parents, H. Musyrifin (almarhum) and Hj. Indo Tang for their love, patience, sincerely prayer for the writer successes and their support materially and emotionally. To the writer’s beloved sisters, Santy Asmarani and Nurjannah A.Md,AK for their supports and helps. 2. The writer’s appreciation is addressed to the rector of Islamic States University of Alauddin Makassar, Prof. -

Jack of Fables Vol. 9: the Ultimate Jack of Fables Story Free

FREE JACK OF FABLES VOL. 9: THE ULTIMATE JACK OF FABLES STORY PDF Bill Willingham,Matthew Sturges,Tony Akins | 144 pages | 19 Jul 2011 | DC Comics | 9781401231552 | English | New York, NY, United Kingdom 9 Love Stories with Tragic Endings | Britannica I savor it, never rushing. I soak it up. It usually makes me smile, first at him, then at myself. This collection of magazine features and columns alongside personally published web pieces and new material may be populated by motorcycles, but it centers around the varied experiences of riders and their tolerant keepers in a world where risk is a bet you make with yourself for purposes that must always transcend mere recreation. Head Check is — beneath the sarcastic wit, wide-eyed fear, profound humility, and occasional Jack of Fables Vol. 9: The Ultimate Jack of Fables Story into scatology — a collection of love stories. Recommended for riders, readers, passengers, and humans. Available from LitsamAmazon and select bookstores and motorcycle shops. More Praise for Head Check. Ask your local bookstore to order it for you. It is also available as an ebook from KindleKoboand Nook. More Praise for Nothing in Reserve. Email Address. Sign me up! Jack Lewis. Purple Hearted was featured in the documentary Muse of Fire. A chapter in progress was published by Crosscut under the headline Remembering the Soldiers of Head Check "Jack Lewis takes the overall literary crown with his new book Jack of Fables Vol. 9: The Ultimate Jack of Fables Story in Reserve "Insightful and from the heart Email Updates! Looking for Something? Something Specific? It was as good a suggestion as any, [ No buddy's puppy The Craigslist picture was unprepossessing — a sad puppy with a blotchy gray coat [ Unexpected consequences There's an old story about Chinese luck.