The University of Hull Bajau Gender

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Narratives of the Dayak People of Sarawak, Malaysia Elizabeth Weinlein '17 Pitzer College

EnviroLab Asia Volume 1 Article 6 Issue 1 Justice, Indigeneity, and Development 2017 Indigenous People, Development and Environmental Justice: Narratives of the Dayak People of Sarawak, Malaysia Elizabeth Weinlein '17 Pitzer College Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/envirolabasia Part of the Anthropology Commons, Asian History Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, East Asian Languages and Societies Commons, Environmental Policy Commons, Environmental Sciences Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Geography Commons, Policy History, Theory, and Methods Commons, Religion Commons, Social Policy Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Weinlein, Elizabeth '17 (2017) "Indigenous People, Development and Environmental Justice: Narratives of the Dayak People of Sarawak, Malaysia," EnviroLab Asia: Vol. 1: Iss. 1, Article 6. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/envirolabasia/vol1/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in EnviroLab Asia by an authorized editor of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Indigenous People, Development and Environmental Justice: Narratives of the Dayak People of Sarawak, Malaysia Cover Page Footnote Elizabeth Weinlein graduated from Pitzer College in 2017, double majoring in Environmental Policy and Asian Studies. For the next year, she has committed to working with the Americorps -

Sabah REDD+ Roadmap Is a Guidance to Press Forward the REDD+ Implementation in the State, in Line with the National Development

Study on Economics of River Basin Management for Sustainable Development on Biodiversity and Ecosystems Conservation in Sabah (SDBEC) Final Report Contents P The roject for Develop for roject Chapter 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background of the Study .............................................................................................. 1 1.2 Objectives of the Study ................................................................................................ 1 1.3 Detailed Work Plan ...................................................................................................... 1 ing 1.4 Implementation Schedule ............................................................................................. 3 Inclusive 1.5 Expected Outputs ......................................................................................................... 4 Government for for Government Chapter 2 Rural Development and poverty in Sabah ........................................................... 5 2.1 Poverty in Sabah and Malaysia .................................................................................... 5 2.2 Policy and Institution for Rural Development and Poverty Eradication in Sabah ............................................................................................................................ 7 2.3 Issues in the Rural Development and Poverty Alleviation from Perspective of Bangladesh in Corporation City Biodiversity -

Internalization and Anti Littering Campaign Implementation

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 85 ( 2013 ) 544 – 553 AcE-Bs 2013 Hanoi ASEAN Conference on Environment-Behaviour Studies Hanoi Architectural University, Hanoi, Vietnam, 19-22 March 2013 "Cultural Sustainability in the Built and Natural Environment" Internalization and Anti Littering Campaign Implementation Haijon Gunggut*, Chua Kim Hing, Dg Siti Noor Saufidah Ag Mohd Saufi Universiti Teknologi MARA, Locked Bag 71, 88997 Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia Abstract This paper seeks to account for the variations in implementation progress of the Anti-litterbugs Campaign in Sabah. A total of nine local authorities were studied. Data was mainly obtained from interviews, observations and written sources. The variation in the Campaign implementation progress can be explained in term of campaign internalization among local authority top leadership. Internalization is reflected in the understanding of the campaign and priority of local government top leaderships observed in their actions, choice of words and activities. In addition, the structure of the local authority also influenced implementation progress. © 2013 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. ©Selection 2013 andPublished peer-review by Elsevierunder responsibility Ltd. Selection of Centre and for peer-review Environment-Behaviour under responsibility Studies (cE-Bs), of the Faculty Centre of Architecture, for Environment- BehPlanningaviour & Surveying,Studies (cE-Bs), Universiti Faculty Teknologi of Architecture,MARA, Malaysia Planning & Surveying, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Malaysia. Keyword: Anti-litterbugs campaign; programme internalization; local government structure; policy implementation 1. Introduction Sabah is one the top biodiversity hotspots in the world and an estimated 2.93 million tourists visited the state in 2012 (Bangkuai, 2012). Unfortunately visitors were often turned off by the presence of litters everywhere. -

TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 405 265 SO 026 916 TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995. Participants' Reports. INSTITUTION Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC.; Malaysian-American Commission on Educational Exchange, Kuala Lumpur. PUB DATE 95 NOTE 321p.; Some images will not reproduce clearly. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) Reports Descriptive (141) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Asian History; *Asian Studies; Cultural Background; Culture; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Foreign Culture; *Global Education; Human Geography; Instructional Materials; *Non Western Civilization; Social Studies; *World Geography; *World History IDENTIFIERS Fulbright Hays Seminars Abroad Program; *Malaysia ABSTRACT These reports and lesson plans were developed by teachers and coordinators who traveled to Malaysia during the summer of 1995 as part of the U.S. Department of Education's Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program. Sections of the report include:(1) "Gender and Economics: Malaysia" (Mary C. Furlong);(2) "Malaysia: An Integrated, Interdisciplinary Social Studies Unit for Middle School/High School Students" (Nancy K. Hof);(3) "Malaysian Adventure: The Cultural Diversity of Malaysia" (Genevieve M. Homiller);(4) "Celebrating Cultural Diversity: The Traditional Malay Marriage Ritual" (Dorene H. James);(5) "An Introduction of Malaysia: A Mini-unit for Sixth Graders" (John F. Kennedy); (6) "Malaysia: An Interdisciplinary Unit in English Literature and Social Studies" (Carol M. Krause);(7) "Malaysia and the Challenge of Development by the Year 2020" (Neale McGoldrick);(8) "The Iban: From Sea Pirates to Dwellers of the Rain Forest" (Margaret E. Oriol);(9) "Vision 2020" (Louis R. Price);(10) "Sarawak for Sale: A Simulation of Environmental Decision Making in Malaysia" (Kathleen L. -

The Effects of Coaching and Mentoring on Metacognition Knowledge Among Malay Language Teachers in Sabah, Malaysia

American International Journal of Education and Linguistics Research Vol. 4, No. 1; 2021 ISSN 2641-7987 E-ISSN 2641-7995 Published by American Center of Science and Education, USA THE EFFECTS OF COACHING AND MENTORING ON METACOGNITION KNOWLEDGE AMONG MALAY LANGUAGE TEACHERS IN SABAH, MALAYSIA Asnia Kadir Kadir School Improvement Specialist Coaches The Education office of Tuaran District, Sabah, Malaysia E-mail: [email protected] Dr. Gunasegaran Karuppannan Associate Professor Faculty of Education and Social Science University of Selangor, Shah Alam, Malaysia E-mail: [email protected] Dr. Mohammad Abdur Rahman Assistant Professor Department of Business Administration, Faculty of Business and Entrepreneurship Daffodil International University, Dhaka, Bangladesh E-mail: [email protected] Dr. Mokana Muthu Kumarasamy Lecturer Faculty of Business and Accountancy University of Selangor, Shah Alam, Malaysia E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT This study was conducted to examine the relationship between coaching and mentoring guidance and the levelof metacognition among Malay language teachers. In 2013, the Ministry of Education Malaysia implemented the District Transformation Programme as a pilot project before it was expanded nationwide in the following year.This step was taken to empowerteachers through the School Improvement Specialist Coaches (SISC) programmethat develop the teachers’ competencies, metacognition and expertise. Using a quantitative approach, the study analysed data were collected from 186 teachersteach in the Tuaran district, Sabah. Study data were analyzed using descriptive and inference analysis. Overall, the findings show that the level of coaching and mentoring is high, thus illustrating that teachers are ready to receive coaching and mentoring guidance in order to develop metacognition ability as well as to improve their teaching and learning performance. -

Language Use and Attitudes As Indicators of Subjective Vitality: the Iban of Sarawak, Malaysia

Vol. 15 (2021), pp. 190–218 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24973 Revised Version Received: 1 Dec 2020 Language use and attitudes as indicators of subjective vitality: The Iban of Sarawak, Malaysia Su-Hie Ting Universiti Malaysia Sarawak Andyson Tinggang Universiti Malaysia Sarawak Lilly Metom Universiti Teknologi of MARA The study examined the subjective ethnolinguistic vitality of an Iban community in Sarawak, Malaysia based on their language use and attitudes. A survey of 200 respondents in the Song district was conducted. To determine the objective eth- nolinguistic vitality, a structural analysis was performed on their sociolinguistic backgrounds. The results show the Iban language dominates in family, friend- ship, transactions, religious, employment, and education domains. The language use patterns show functional differentiation into the Iban language as the “low language” and Malay as the “high language”. The respondents have positive at- titudes towards the Iban language. The dimensions of language attitudes that are strongly positive are use of the Iban language, Iban identity, and intergenera- tional transmission of the Iban language. The marginally positive dimensions are instrumental use of the Iban language, social status of Iban speakers, and prestige value of the Iban language. Inferential statistical tests show that language atti- tudes are influenced by education level. However, language attitudes and useof the Iban language are not significantly correlated. By viewing language use and attitudes from the perspective of ethnolinguistic vitality, this study has revealed that a numerically dominant group assumed to be safe from language shift has only medium vitality, based on both objective and subjective evaluation. -

Tuaran-Instrument1961 0.Pdf

FOR REFERENCE ONLY (April 2017) [Am: G.N.S. 14/2004 (20.12.2004), G.N.S. 23/2012 (03.01.2013)] LOCAL GOVERNMENT ORDINANCE 1961 (No. 11 of 1961) TUARAN DISTRICT COUNCIL INSTRUMENT 1961 (G.N.S 174 of 1961) INSTRUMENT issued by the Governor in Council under the provisions of section 3 of the Local Government Ordinance 1961. 1. This Instrument may be cited as the Tuaran District Council Instrument 1961. 2. In this Instrument — "Council" means the Tuaran District Council established by clause 3 of this Instrument; "Ordinance" means the Local Government Ordinance 1961. 3. There is hereby established with effect from the 1st day of January 1962 a District Council to be known as the Tuaran District Council. 4. (1) The limits of the area under the jurisdiction of the District Council are as defined in the First Schedule hereto. (2) The areas set out in the Second Schedule hereto are declared to be townships to be known as Tuaran, Tamparuli, Tenghilan and Kiulu Townships. (3) The area set out in the First Schedule is declared as rating area and shall be subjected to rates as prescribed by the order made under section 82 of the Ordinance. 1 FOR REFERENCE ONLY (April 2017) 5. The seal of the Council shall be the following device: A circle with the words "Tuaran District Council" around the circumference: Provided that until such time as a seal capable of reproducing the said device can be procured a rubber stamp bearing the inscription "Tuaran District Council" may be used in lieu of such seal. -

Abstracts for the 1St International Borneo Healthcare and Public Health Conference and 4Th Borneo Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease Congress

Malaysian Journal of Medicine and Health Sciences Vol.15 Supp 6, October 2019 (eISSN 2636-9346) ABSTRACTS FOR THE 1ST INTERNATIONAL BORNEO HEALTHCARE AND PUBLIC HEALTH CONFERENCE AND 4TH BORNEO TROPICAL MEDICINE AND INFECTIOUS DISEASE CONGRESS New Frontiers in Health: Expecting the Unexpected Held at the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia On 3rd-5th September 2019 Proceedings of the IBPHC 3-5 September 2019 Malaysian Journal of Medicine and Health Sciences Vol.15 Supp 6, October 2019 (eISSN 2636-9346) Editorial Information Scientific Committee/Abstract Editors Prof. Dr. Mohammad Saffree Jeffree, Universiti Malaysia Sabah (Advisor) Dr. Timothy William, Infectious Diseases Society Kota Kinabalu (Advisor) Datuk Dr. Mohd Yusof Hj Ibrahim, Universiti Malaysia Sabah (Chairman) Dr. Giri Shan Rajahram, Infectious Diseases Society Kota Kinabalu (Chairman) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Richard Avoi, Universiti Malaysia Sabah (Head of Scientific Committee) Prof. Dr. Kamruddin Ahmed, Universiti Malaysia Sabah Assoc. Prof. Dr. Syed Sharizman, Universiti Malaysia Sabah Assoc. Prof. Dr. Naing Oo Tha, Universiti Malaysia Sabah Assoc. Prof. Dr. Shamsul Bahari Shamsudin, Universiti Malaysia Sabah Assoc. Prof. Dr. Fredie Robinson, Universiti Malaysia Sabah Assoc. Prof. Dr. Kamarul Imran Musa, Universiti Sains Malaysia Assoc. Prof. Dr. Mohd Rohaizat Hassan, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Dr. Caroline Sunggip, Universiti Malaysia Sabah Dr. Lim Jac Fang, Universiti Malaysia Sabah Dr. Tan Bih Yuan, Universiti -

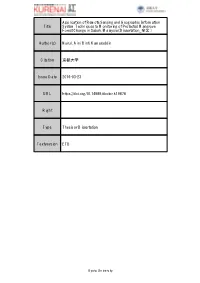

Title Application of Remote Sensing and Geographic Information System Techniques to Monitoring of Protected Mangrove Forest Chan

Application of Remote Sensing and Geographic Information Title System Techniques to Monitoring of Protected Mangrove Forest Change in Sabah, Malaysia( Dissertation_全文 ) Author(s) Nurul, Aini Binti Kamaruddin Citation 京都大学 Issue Date 2016-03-23 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/doctor.k19878 Right Type Thesis or Dissertation Textversion ETD Kyoto University Application of Remote Sensing and Geographic Information System Techniques to Monitoring of Protected Mangrove Forest Change in Sabah, Malaysia 2016 NURUL AINI BINTI KAMARUDDIN Acknowledgement First and foremost, I would like to give my sincere thanks to my supervisor, Prof. Shigeo Fujii, who has accepted me as his Ph.D. student and offered me so much advice, patiently supervising me and always guiding me in the right direction. I have learned a lot from him. Without his help, I could not have finished my desertion successfully. Special thanks also go to Assoc. Prof. Shuhei Tanaka. He is the one who offered me the opportunity to study at Kyoto University during his visiting research in Malaysia in 2008. I am thankful to Dr. Binaya Raj Shivakoti for his kindness and sharing his knowledge on remote sensing techniques. He is the one who helps me very much how to use the remote sensing software and analyzed the satellite data. Many thanks are also due Asst. Prof. Hidenori Harada for his advised and suggestions. I would like to express my gratitude to Prof. Datin Sri Panglima Dr. Hajjah Ann Anton at University Malaysia Sabah (UMS), Malaysia for her valuable support and collaboration during the sampling in Sabah. Also, I would like to thank to all her staff at the Kota Kinabalu Wetlands Centre and UMS students for assisting and supporting me during my internship in Sabah. -

Ethnoscape of Riverine Society in Bintulu Division Yumi Kato Hiromitsu Samejima Ryoji Soda Motomitsu Uchibori Katsumi Okuno Noboru Ishikawa

No.8 February 2014 8 Reports from Project Members Ethnoscape of Riverine Society in Bintulu Division Yumi Kato Hiromitsu Samejima Ryoji Soda Motomitsu Uchibori Katsumi Okuno Noboru Ishikawa ........................................ 1 Events and Activities Reports on Malaysian Palm Oil Board Library etc. Jason Hon ............................................................................................ 15 The List of Project Members ........................................................ 18 Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (S) In front of a longhouse of Tatau people at lower Anap River March 2013 (Photo by Yumi Kato) Reports from Project Members division has more non-Malaysian citizens, Iban and Ethnoscape of Riverine Society in Melanau people than other areas and less Chinese Bintulu Division and Malay residents. Yumi Kato (Hakubi Center for Advanced Research, Kyoto University) Hiromitsu Samejima (Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Historically, the riverine areas of the Kemena and Kyoto University) Ryoji Soda (Graduate School of Literature and Human Tatau were under the rule of the Brunei sultanate until Sciences, Osaka City University) the late 19th century and the areas were nothing but Motomitsu Uchibori (Faculty of Liberal Arts, The Open University of Japan) sparsely-populated uncultivated land (Tab. 1). Back Katsumi Okuno (College of Liberal Arts, J.F. Oberlin then the Vaie Segan and Penan inhabited the basin University) Noboru Ishikawa (Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University) Other-Malaysian Introduction Citizens Non-Malaysian 0% Citizens The study site of this project is the riverine areas Orang Ulu 21% Iban 5% 40% Bidayuh 1% of the Kemena and Tatau Rivers in the Bintulu Divi- Malay 9% sion. This article provides an overview of the ethnic Melanau Chinese groups living along those rivers. -

INDIGENOUS GROUPS of SABAH: an Annotated Bibliography of Linguistic and Anthropological Sources

INDIGENOUS GROUPS OF SABAH: An Annotated Bibliography of Linguistic and Anthropological Sources Part 1: Authors Compiled by Hans J. B. Combrink, Craig Soderberg, Michael E. Boutin, and Alanna Y. Boutin SIL International SIL e-Books 7 ©2008 SIL International Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2008932444 ISBN: 978-155671-218-0 Fair Use Policy Books published in the SIL e-Books series are intended for scholarly research and educational use. You may make copies of these publications for research or instructional purposes (under fair use guidelines) free of charge and without further permission. Republication or commercial use of SILEB or the documents contained therein is expressly prohibited without the written consent of the copyright holder(s). Series Editor Mary Ruth Wise Volume Editor Mae Zook Compositor Mae Zook The 1st edition was published in 1984 as the Sabah Museum Monograph, No. 1. nd The 2 edition was published in 1986 as the Sabah Museum Monograph, No. 1, Part 2. The revised and updated edition was published in 2006 in two volumes by the Malaysia Branch of SIL International in cooperation with the Govt. of the State of Sabah, Malaysia. This 2008 edition is published by SIL International in single column format that preserves the pagination of the 2006 print edition as much as possible. Printed copies of Indigenous groups of Sabah: An annotated bibliography of linguistic and anthropological sources ©2006, ISSN 1511-6964 may be obtained from The Sabah Museum Handicraft Shop Main Building Sabah Museum Complex, Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, -

A Study on Tuaran River Channel Planform and the Effect of Sand Extraction on River Bed Sediments

Transactions on Science and Technology Vol. 4, No. 4, 442 - 448, 2017 A Study on Tuaran River Channel Planform and the Effect of Sand Extraction on River Bed Sediments Jayawati Montoi1#, Siti Rahayu Mohd. Hashim2, Sanudin Tahir1 1 Geology Programme, Faculty of Science and Natural Resources, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Jalan UMS, 88400 Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, MALAYSIA. 2 Mathematic With Economic Programme, Faculty of Science and Natural Resources, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Jalan UMS, 88400 Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, MALAYSIA. # Corresponding author. E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel: +6088-260311; Fax: +6088-240150. ABSTRACT River sand extraction is known as one of the main factors that induces the significant changes on river planform. This paper main objective is to study on the significance of planform changes on Tuaran River from 2003 to 2016 and sediment composition changes due to this activity. The study on channel planform focuses on four single wavelength channel bends which are located at the downstream of Tuaran River. Two meander features which are the channel width (w) and radius of curvature (Rc) were measured from digitized Google Earth satellite image year 2003, 2013, 2014 and 2016 and overlay with the Department of Survey and Mapping Malaysia (JUPEM) topographic map using Geographic Information System (GIS) software and georeferenced to World Geodetic System (WGS) 1984. Four sites which are located at the downstream of Tuaran River were selected to determine the river bed sediments composition. Three of the four sites are located at the sand extraction area whilst one site is a controlled area with no sand extraction activity. River bed sediments were collected and the sediments composition was analyzed using Mann Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests to determine the composition difference between the areas and the inner parts of the river.