The Legality of the Bowe Bergdahl Prisoner Swap

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAAF Bergdahl Writ Appeal Petition

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ARMED FORCES ROBERT B. BERGDAHL ) WRIT-APPEAL PETITION FOR Sergeant, U.S. Army, ) REVIEW OF U.S. ARMY COURT OF ) CRIMINAL APPEALS DECISION ON Appellant, ) PETITION FOR WRIT OF MANDAMUS ) v. ) ) PETER Q. BURKE ) Lieutenant Colonel, AG ) U. S. Army, ) in his official capacity as ) Commander, Special Troops ) Battalion, U. S. Army Forces ) Crim. App. Misc. Dkt. No. Command, Fort Bragg, NC, and ) ARMY 20150624 Special Court-Martial ) Convening Authority, ) USCA Misc. Dkt. No. ) and ) ) UNITED STATES, ) ) Appellees. ) TO THE HONORABLE, THE JUDGES OF THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ARMED FORCES: Index Table of Authorities .......................................... ii I. Preamble and Request for Recusal ............................ 1 II. History of the Case ........................................ 3 III. Reasons Relief Not Sought Below [Inapplicable] ............ 6 IV. Relief Sought .............................................. 6 V. Issue Presented ............................................. 6 ONCE AN UNCLASSIFIED DOCUMENT HAS BEEN ACCEPTED IN EV- IDENCE IN A PRELIMINARY HEARING THAT IS OPEN TO THE PUBLIC, MAY THE CONVENING AUTHORITY REFUSE TO RELEASE IT OR PERMIT THE ACCUSED TO DO SO? VI. Statement of Facts ......................................... 6 VII. Reasons Why Writ Should Issue ............................. 6 A. Jurisdiction ............................................. 6 B. Error ................................................... 13 C. Prudential Considerations .............................. -

Political Report

A M ONTHLYPolitical P OLL C O mp IL A TION Report Volume 10, Issue 6 • June 2014 Evaluating Vice Presidents Americans have never held the office of vice president in high regard, as the quotes below show. Many people cannot cor- rectly identify vice presidents when they are serving, and this is not a new phenomenon. In 2010, around six in ten Amer- icans were able to come up with Joe Biden’s name in response to a question from the Pew Research Center. As the data on the next pages show, a vice president’s favorability ratings have usually moved in tandem with the president’s ratings in recent years, but the vice president’s ratings are usually lower. The most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived or his imagination conceived. —John Adams Not worth a bucket of warm spit. —John Nance Gardner I do not propose to be buried until I am dead. —Daniel Webster of being asked to be Zachary Taylor’s running mate Q: Will you tell me who the Vice President of the United States is? (1952, Gallup) Q: Who is the Vice President of the United States? (1978, National Opinion Research Center) Q: Can you tell me the name of the current Vice President of the United States? (1995, Kaiser/Harvard/Washington Post). Q: Will you tell me who the Vice President of the United States is? (2001, 2002, 2007, 2010 – question wording varied slightly, Pew Research Center) 1952 1978 Alben Barkley 69% Walter Mondale 79% 1995 Al Gore 60% Dick Cheney 2001 67% 2002 61 2007 69 2010 Joe Biden 59% v AEI POLITICAL REPORT CONTRIBUTORS Karlyn Bowman, Senior Fellow; Editors: Jennifer Marsico, Senior Research Norman Ornstein, Resident Scholar; Associate; Heather Sims, Research Assistant. -

Motion to Dismiss ) V

IN A GENERAL COURT-MARTIAL SECOND JUDICIAL CIRCUIT, U.S. ARMY TRIAL JUDICIARY FORT BRAGG, NORTH CAROLINA UNITED STATES ) Motion to Dismiss ) v. ) ) SGT Robert B. Bergdahl ) HHC, Special Troops Battalion ) U.S. Army Forces Command ) Fort Bragg, North Carolina 28310 ) 20 January 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Relief Sought ................................................................................................................... 2 Burden of Persuasion and Burden of Proof ..................................................................... 2 Facts ............................................................................................................................... 3 Witnesses and Evidence ................................................................................................. 7 Legal Authority ................................................................................................................ 8 Question Presented......................................................................................................... 9 IS DISMISSAL REQUIRED WHERE A SUCCESSFUL PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE HAS, AS A PROMINENT ELEMENT OF HIS CAMPAIGN, REPEATEDLY AND VERY PUBLICLY CALLED A SOLDIER A TRAITOR WHO SHOULD BE EXECUTED AND MADE OTHER FALSE AND HIGHLY PREJUDICIAL STATEMENTS ABOUT THE SOLDIER’S CASE? Argument ......................................................................................................................... 9 I. President Trump’s statements are prejudicial to Sergeant Bergdahl’s right to a fair trial and -

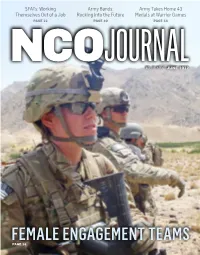

Sfats: Working Themselves out of a Job Army Bands

SFATs: Working Army Bands: Army Takes Home 43 Themselves Out of a Job Rocking Into the Future Medals at Warrior Games PAGE 22 PAGE 30 PAGE 48 VOL. 21, NO. 6 · JUNE 2012 FEMALE ENGAGEMENT TEAMS PAGE 14 The Official Magazine of NCO Professional Development VOLUME 21, NUMBER 6 Editorial Staff DIRECTOR & NCOIC Master Sgt. Antony M.C. Joseph EDITOR David Crozier CONTENTS WRITERS / EDITORS Staff Sgt. Jason Stadel Michael L. Lewis Clifford Kyle Jones Jonathan (Jay) Koester Christy Lattimore-Staple Jennifer Mattson PHOTOGRapHY & GRapHICS Sgt. Russel C. Schnaare Spc. Ashley Arnett Published monthly at the June 2012 United States Army Sergeants Major FeaTURES Academy 14 Behind the veil Editorial Board Female engagement teams interact with local women to bring stability to COMManDanT, USASMA combat troops and local communities. BY JENNIFER MATTSON Command Sgt. Maj. Rory L. Malloy 22 Working themselves out of a job DepuTY COMManDanT Command Sgt. Maj. Wesley Weygandt Security Force Assistance Teams embed with Afghan soldiers and police to advise and assist with setting up security. BY DAVID CroZier CHIEF OF STAFF Stephen L. Chase 30 Marching Rocking into the future DIRECTOR PERSOnneL & ADMIN. NCOs of Army Bands are adapting to remain relevant. BY JONATHAN (JAY) KOESTER Jesse McKinney 36 Old uniforms, modern mission The NCO Journal (ISSN 1058-9058) is published monthly by the U.S. Army The Fife & Drum Corps is among the most visible Army units. BY MICHAEL L. LEWIS Sergeants Major Academy to provide a forum for the open exchange of ideas DepaRTMenTS and information pertinent to the Noncommis- sioned Officer Corps; to support training, educa- tion and development of the NCO Corps; and to 3 From the CSM foster a closer bond among its members. -

Military Appellate Court: Presidential Comments Can Amount to Unlawful Command Influence

Legal Sidebari Military Appellate Court: Presidential Comments Can Amount to Unlawful Command Influence November 2, 2020 In a set of divided opinions on August 27, the U.S Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces (CAAF) rejected Sergeant Robert “Bowe” Bergdahl’s appeal in his desertion case, which he argued was invalid due to unlawful command influence. However, CAAF found that the President’s remarks about an ongoing court-martial trial can amount to unlawful command influence in violation of Art. 37 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ). The court reasoned that the President is by statute a convening authority for general courts-martial and is therefore subject to the Rules for Courts-Martial (R.C.M.) Rule 104(a)’s prohibition on unlawful command influence, which implements Art. 37 of the UCMJ. The court also held that the late Senator John McCain’s actions as Chair of the Senate Armed Forces Committee regarding a pending court-martial could have violated Art. 37 of the UCMJ because Senator McCain, as a retired member of the Armed Forces, was a person subject to the UCMJ. However, under the facts of the case, a CAAF majority held there was no apparent unlawful command influence, affirming the lower court’s determination that appellant Bergdahl was not entitled to relief. This Legal Sidebar explains the prohibition against unlawful command influence in military courts, describes the tests CAAF uses to decide whether unlawful command influence has occurred, and explains CAAF’s decision in the Bergdahl appeal. For more information about military courts-martial, see this CRS Report. -

November 2017 Volume 9, Issue 4

Proceedings A monthly newsletter from McGraw-Hill Education November 2017 Volume 9, Issue 4 Contents Dear Professor, Hot Topics 2 Video Suggestions 15 Happy fall season, everyone! Welcome to McGraw-Hill Education’s November 2017 issue of Proceedings, a newsletter designed specifically with Ethical Dilemma 21 you, the Business Law educator, in mind. Volume 9, Issue 4 of Proceedings Teaching Tips 32 incorporates “hot topics” in business law, video suggestions, an ethical dilemma, teaching tips, and a “chapter key” cross-referencing the November Chapter Key 35 2017 newsletter topics with the various McGraw-Hill Education business law textbooks. You will find a wide range of topics/issues in this publication, including: 1. The Harvey Weinstein sexual harassment scandal; 2. A recent sexual harassment scandal in the United States military; 3. Constitutional (free speech) issues related to President Donald Trump’s Twitter account; 4. Videos related to a) a case involving due process in the United States military and b) Senator Hillary Clinton’s claim that sexism and racism are “endemic” in America; 5. An “ethical dilemma” related to the opioid crisis in the United States; and 6. “Teaching tips” related to Article 1 (“Harvey Weinstein Paid Off Sexual Harassment Accusers for Decades”), Article 2 (“Army Sacks General for Sexy Texts to Wife of a Sergeant”), and Video 2 (“Hillary Clinton: Misogyny is ‘Endemic’”) of the newsletter. I wish all of you a fantastic remainder of the fall semester! Jeffrey D. Penley, J.D. Catawba Valley Community College -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2014 Statement on the Release Of

Administration of Barack Obama, 2014 Statement on the Release of Sergeant Bowe R. Bergdahl, USA, From Captivity by Taliban Forces in Afghanistan May 31, 2014 Today the American people are pleased that we will be able to welcome home Sergeant Bowe Bergdahl, held captive for nearly 5 years. On behalf of the American people, I was honored to call his parents to express our joy that they can expect his safe return, mindful of their courage and sacrifice throughout this ordeal. Today we also remember the many troops held captive and whom remain missing or unaccounted for in America's past wars. Sergeant Bergdahl's recovery is a reminder of America's unwavering commitment to leave no man or woman in uniform behind on the battlefield. And as we find relief in Bowe's recovery, our thoughts and prayers are with those other Americans whose release we continue to pursue. For his assistance in helping to secure our soldier's return, I extend my deepest appreciation to the Amir of Qatar. The Amir's personal commitment to this effort is a testament to the partnership between our two countries. The United States is also grateful for the support of the Government of Afghanistan throughout our efforts to secure Sergeant Bergdahl's release. This week, the United States renewed its commitment to the Afghan people and made clear that we will continue to support them as their chart their own future. The United States also remains committed to supporting an Afghan-led reconciliation process as the surest way to achieve a stable, secure, sovereign, and unified Afghanistan. -

The Legality of the Bowe Bergdahl Prisoner Swap

Buffalo Law Review Volume 63 Number 5 Article 6 12-1-2015 Leave No Soldier Behind? The Legality of the Bowe Bergdahl Prisoner Swap Steven M. Maffucci University at Buffalo School of Law (Student) Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview Part of the Military, War, and Peace Commons, and the National Security Law Commons Recommended Citation Steven M. Maffucci, Leave No Soldier Behind? The Legality of the Bowe Bergdahl Prisoner Swap, 63 Buff. L. Rev. 1325 (2015). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview/vol63/iss5/6 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Buffalo Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENT Leave No Soldier Behind? The Legality of the Bowe Bergdahl Prisoner Swap STEVEN M. MAFFUCCI† INTRODUCTION On May 31, 2014, President Obama announced the recovery of the lone American prisoner of war from the Afghan conflict, U.S. Army Sergeant Bowe Bergdahl.1 This seemingly momentous occasion, however, was quickly shrouded in controversy.2 Most notably, there were assertions from members of Bergdahl’s unit that he had deserted, and that fellow soldiers had needlessly died in the search following Bergdahl’s disappearance.3 There were complaints that the cost associated with recovering Bergdahl, particularly the five Taliban prisoners for whom Bergdahl was exchanged, was too high, and that the Obama † J.D. -

PRISM Vol. 4 No 4

FEATURES 2 Egypt in Transition: The Third Republic By M. Cherif Bassiouni 21 Talking to the Taliban 2011 - 2012: A Reflection By Marc Grossman www.ndu.edu 38 Strategic Terrorism: A Call to Action ndupress.ndu.edu By Nathan P. Myhrvold 57 Hybridization of Conflicts By Alain Bauer 67 Putting State Legitimacy at the Center of Foreign Operations and Assistance By Bruce Gilley 86 Rules of Engagement and Abusive Citizens By Amitai Etzioni 104 A Swift and Decisive Victory: The Strategic Implications of What Victory Means By Chong Shi Hao 118 Evolving Internal Roles of the Armed Forces: Lessons for Building Partner Capacity By Albrecht Schnabel and Marc Krupanski FROM THE FIELD 138 LESSONS LEARNED 138 Confronting the Threat of Corruption and Organized Crime in Afghanistan:Implications for Future Armed Conflict By Tim Sullivan and Carl Forsberg BOOK REVIEWS 156 Women and Wars Reviewed By Kristen A. Cordell 160 The End of Power Reviewed By Amy Zalman INTERVIEW 163 An Interview with Lieutenant General Mike Flynn Muhammed Ghafari Day of Anger Marchers, January 25, 2011 Egypt in Transition The Third Republic BY M. CHERIF BASSIOUNI n January 25, 2011, the Egyptian people took to the streets and in 18 days were able to bring down the 30-year corrupt dictatorial regime of Hosni Mubarak, using entirely Opeaceful means. That revolution set the Arab Republic of Egypt on a hopeful path to democracy. After Mubarak resigned, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) became the custodian of the transition. In June of 2012, in Egypt’s first free and fair presidential election, Muslim Brotherhood candidate Mohammed Morsi was elected President. -

Donald Trump As Global Constitutional Breaching Experiment Jonathan Havercroft Antje Wiener Mattias Kumm Jeffrey L

Donald Trump as Global Constitutional Breaching Experiment Jonathan Havercroft Antje Wiener Mattias Kumm Jeffrey L. Dunoff The publication of this issue of Global Constitutionalism comes a little over a year since Donald Trump was sworn in as President of the United States. Over the ensuing thirteen months it has become commonplace to observe that the actions of this President are “not normal”. Examples of his abnormal behavior are numerous, but for a quick refresher consider the following (very incomplete) list. Calling the director of the National Parks Service to find photos of the inauguration to disprove media claims that President Obama’s inauguration had a larger audience.1 Launching an investigation into voter fraud over the election he won, without any actual evidence of voter fraud.2 Hanging up on the Australian Prime Minister because he did not like a pre-existing refugee agreement between the U.S. and Australia.3 Pressuring the director of the FBI to stop investigating Michael Flynn for he undisclosed dealings with Russia and Turkey. Banning major media outlets from White House press briefings because he did not like the coverage he received from these organizations.4 Accusing President Obama of wire tapping Trump’s offices in Trump Tower.5 Attacking courts and judges who have ruled against him on the “Muslim travel ban”.6 Leaking classified intelligence from a U.S. ally (widely reported in the press to be Israel) to the Ambassador of Russia.7 Firing the director of the FBI because of an ongoing 1 “Donald Trump Personally Called National Park Service Director about Those Inauguration Photos,” The Independent, January 27, 2017, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/donald-trump-national-park-service- michael-reynolds-inauguration-crowd-size-photos-proof-a7548601.html. -

Fair Trade: the President's Power to Recover Captured U.S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Fordham University School of Law Fordham Law Review Volume 83 Volume 83 Issue 5 Volume 83, Issue 5 Article 22 2015 Fair Trade: The President’s Power to Recover Captured U.S. Servicemembers and the Recent Prisoner Exchange with the Taliban Celidon Pitt Fordham University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law and Politics Commons, Military, War, and Peace Commons, National Security Law Commons, and the President/Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation Celidon Pitt, Fair Trade: The President’s Power to Recover Captured U.S. Servicemembers and the Recent Prisoner Exchange with the Taliban, 83 Fordham L. Rev. 2837 (2015). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol83/iss5/22 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FAIR TRADE: THE PRESIDENT’S POWER TO RECOVER CAPTURED U.S. SERVICEMEMBERS AND THE RECENT PRISONER EXCHANGE WITH THE TALIBAN Celidon Pitt* The Obama Administration’s controversial exchange of five Taliban detainees for a captured U.S. soldier in May 2014 reignited a heated debate over the proper scope of wartime executive authority. From a legal perspective, the primary issue centers on the constitutional balance of power between congressional appropriations and the President’s power as Commander in Chief. -

As Prepared / Embargoed Until Delivery 6/11/2014 1

AS PREPARED / EMBARGOED UNTIL DELIVERY SECRETARY OF DEFENSE CHUCK HAGEL HEARING ON THE TRANSFER OF DETAINEES HOUSE ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEE WASHINGTON, DC WEDNESDAY, JUNE 11, 2014 Chairman McKeon, Ranking Member Smith, members of the committee. I appreciate the opportunity to discuss the recovery of Sergeant Bowe Bergdahl, and the transfer of five detainees from Guantanamo Bay to Qatar. And I appreciate having the Department of Defense General Counsel Stephen Preston, here with me. Mr. Preston was one of our negotiators in Qatar and signed on behalf of the U.S. the Memorandum of Understanding between the Governments of Qatar and the United States. Also here representing the Joint Chiefs of Staff is Brigadier General Pat White, who is the Director of the Joint Staff’s Pakistan/Afghanistan Coordination Cell and who helped coordinate the Bergdahl recovery on behalf of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Dempsey. The Vice Chairman of the Joints Chiefs, Admiral Winnefeld, will join us for the closed portion of this hearing. As you know, General Dempsey and Admiral Winnefeld played a critical role in the meetings at the National Security Council leading up to Sergeant Bergdahl’s release and supported the decision to move forward with this prisoner exchange. In my statement today, I will address the issues Chairman McKeon raised when he asked me to testify, and explain why it was urgent to pursue Sergeant Bergdahl’s release, why we decided to move forward with the detainee transfer, and why it was fully consistent with U.S. law, our nation’s interests, and our military’s core values.