2010 Seattlepi Chainsaw

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pwc”) to Serve As Independent Auditor and Tax Compliance Services Provider for the Debtors, Effective As of February 18, 2020

Case 20-10343-LSS Doc 796 Filed 06/05/20 Page 1 of 16 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE In re: Chapter 11 BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA AND Case No. 20-10343 (LSS) DELAWARE BSA, LLC,1 (Jointly Administered) Debtors. Hearing Date: July 9, 2020 at 10:00 a.m. (ET) Objection Deadline: June 19, 2020 at 4:00 p.m. (ET) DEBTORS’ APPLICATION FOR ENTRY OF AN ORDER AUTHORIZING THE RETENTION AND EMPLOYMENT OF PRICEWATERHOUSECOOPERS LLP AS INDEPENDENT AUDITOR AND TAX COMPLIANCE SERVICES PROVIDER FOR THE DEBTORS AND DEBTORS IN POSSESSION, EFFECTIVE AS OF FEBRUARY 18, 2020 The Boy Scouts of America (the “BSA”) and Delaware BSA, LLC, the non-profit corporations that are debtors and debtors in possession in the above-captioned chapter 11 cases (together, the “Debtors”), submit this application (this “Application”), pursuant to section 327(a) of title 11 of the United States Code (the “Bankruptcy Code”), rules 2014(a) and 2016 of the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure (the “Bankruptcy Rules”), and rules 2014-1 and 2016-2 of the Local Rules of Bankruptcy Practice and Procedure of the United States Bankruptcy Court for the District of Delaware (the “Local Rules”), for entry of an order, substantially in the form attached hereto as Exhibit A (the “Proposed Order”), (i) authorizing the Debtors to retain and employ PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP (“PwC”) to serve as independent auditor and tax compliance services provider for the Debtors, effective as of February 18, 2020 (the “Petition Date”), pursuant to the terms and conditions of the Engagement Letters (as defined 1 The Debtors in these chapter 11 cases, together with the last four digits of each Debtor’s federal tax identification number, are as follows: Boy Scouts of America (6300) and Delaware BSA, LLC (4311). -

COVID-19 Information Pathway to Adventure Council, Boy Scouts of America

COVID-19 Information Pathway to Adventure Council, Boy Scouts of America The Pathway to Adventure Council requires all persons attending Scouting events, activities, or meetings to adhere to the City of Chicago’s “Protecting Chicago” Reopening Framework. Due to the ever- changing nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, all unit/event/activity/meeting leadership must review and adhere to the City of Chicago’s latest restrictions and guidance, which is regularly updated on their website. If you are visiting a city, state, or area with stricter requirements, you MUST follow the stricter requirements of the place you are visiting. Additionally, all persons attending Scouting events, activities, or meetings must adhere to the Guide to Safe Scouting, the BSA Restarting Scouting Checklist, and Scouts and Scouters should have a current BSA Annual Health and Medical form, part A and B on file with their unit. These procedures and health forms are required for all Scouting activities and events, including unit meetings, Order of the Arrow gatherings, district events, council events, and service projects, such as Eagle Scout projects. During any Scouting event, activity, or meeting, all attendees must: . Practice social distancing and wear a face mask, except during physical activity.* Physical activity includes free play, games, sports, transportation (walking, cycling, hiking), and recreation. o Youth protection guidelines must still be followed. Frequently touched surfaces should be cleaned after each use. All Scouts, leaders, and family members should stay home if they feel ill or have come into contact with someone with COVID-19. *Children under 2 years old and those with health conditions that prevent them from wearing a mask are exempt from this precaution. -

Central Region Directory 2009—2010

CENTRAL REGION DIRECTORY 2009—2010 OFFICERS Regional President Regional Commissioner Regional Director Stephen B. King Brian P. Williams Jeffrie A. Herrmann King Capital, LLC Partner Central Region, BSA Founder, Partner Kahn, Dees, Donovan & Kahn, LLP 1325 W. Walnut Hill Lane 3508 N. Edgewood Dr. PO Box 3646 PO Box 152079 Janesville, WI 53545 Evansville, IN 47735-3646 Irvine, TX 75015-2079 Phone: 608.755.8162 Phone: 812.423.3183 Phone: Fax: 608.755.8163 Fax: 812.423.6066 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Vice President of Vice President Vice President Vice President Strategic Initiatives Finance & Endowment Outdoor Adventure Council Solutions Joseph T. Koch Ronald H. Yocum Steven McGowan Charles T. Walneck COO 9587 Palaestrum Rd. Steptoe & Johnson, PLLC Chairman, President & CEO Fellowes, Inc. Williamsburg, MI 49690 PO Box 1588 SubCon Manufacturing Corp. 1789 Norwood Ave. Phone: 231.267.9905 Chase Tower 8th Fl. 201 Berg St. Itasca, IL 60143-1095 Fax: 231.267.9905 Charleston, WV 25326 Algonquin, IL 60102 Phone: 630.671.8053 [email protected] Phone: 304.353.8114 Phone: 847.658.6525 Fax: 630.893.7426 (June-Oct.) Fax: 304.626.4701 Fax: 847.658.1981 [email protected] [email protected] steven.mcgowan [email protected] (Nov.-May) @steptoe-johnson.com Vice President Vice President Nominating Committee Appeals Committee Marketing LFL/Exploring Chairman Chairman Craig Fenneman Brad Haddock R. Ray Wood George F. Francis III President & CEO Haddock Law Office, LLC 1610 Shaw Woods Dr. Southern Bells, Inc. 19333 Greenwald Dr. 3500 North Rock Road, Building 1100 Rockford, IL 61107 5864 S. -

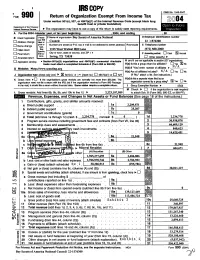

Srs Copy 2004

SRS COPY OMB No . 1545-0047 Fo,m 990 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Under section 501(c), 52;x, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung benefit trust w private foundation) 2004 Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Samoa t The organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements . A For the 2004 calendar year, or tax year beginning , 2004, and ending , 20 D Employer B Check if applicable : Please C Name of organization Boy Stoats of America National Identification number use :RS Address change label or Council 22 .1576300 print or Number and sweet (or P.O. box it mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number D Name change D Initial return ~ 1325 West Walnut Hill Lane (972) 580-2000 Specific , city or town, state or count and ZIP + 4 0 Final return in~NC- y N~ F Accounting method: El Cash N Accrual tans. Irving, TX 75038 D Amended return D Other (specify) t H and 1 are not applicable to section 527 orga, nizafions. D Application pending " Section 501(e)(3) organizations end 4947(ax1) nonexempt charitable trusts must attach a completed Schedule A (Form 990 or 990-Q). H(a) IS this a group return for affiliates? El Y ~ No N ~A G Website: H(b) If 'Yes ; enter number of affiliates ~ , _ . .. .. H(c) Are all affiliates included? N / A E ]Yes E]No J Organization type (check only one) t IR 501(c) ( 3 ) ,4 (insert no .) 0 4947(a)(1) or [1 527 (If 'No,' attach a list. -

A Cartographic Depiction and Exploration of the Boy Scouts of America’S Historical Membership Patterns

A Cartographic Depiction and Exploration of the Boy Scouts of America’s Historical Membership Patterns BY Matthew Finn Hubbard Submitted to the graduate degree program in Geography and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ____________________________ Chairperson Dr. Stephen Egbert ____________________________ Dr. Terry Slocum ____________________________ Dr. Xingong Li Date Defended: 11/22/2016 The Thesis committee for Matthew Finn Hubbard Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: A Cartographic Depiction and Exploration of the Boy Scouts of America’s Historical Membership Patterns ____________________________ Chairperson Dr. Stephen Egbert Date approved: (12/07/2016) ii Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to examine the historical membership patterns of the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) on a regional and council scale. Using Annual Report data, maps were created to show membership patterns within the BSA’s 12 regions, and over 300 councils when available. The examination of maps reveals the membership impacts of internal and external policy changes upon the Boy Scouts of America. The maps also show how American cultural shifts have impacted the BSA. After reviewing this thesis, the reader should have a greater understanding of the creation, growth, dispersion, and eventual decline in membership of the Boy Scouts of America. Due to the popularity of the organization, and its long history, the reader may also glean some information about American culture in the 20th century as viewed through the lens of the BSA’s rise and fall in popularity. iii Table of Contents Author’s Preface ................................................................................................................pg. -

July 28 Golf Course

26TH ANNUAL JAMAR - BSA GOLF CLASSIC ENGER PARK JULY 28 GOLF COURSE 1801 W SKYLINE PKWY SHOTGUN START DULUTH, MN 55806 HOLE IN ONE - CLOSEST TO THE PIN - SCOUT PUP TENT MONEY HOLE - LONGEST PUTT - TOP 3 TEAMS SNACK BAG - DINNER - PROGRAM All proceeds benefit the Voyageurs Area Council, BSA to support development of youth Scouting programs in northern Minnesota, northern Wisconsin, and Gogebic County in Michigan, and provide a $2500 scholarship to a Council Eagle Scout. JAMAR - BSA GOLF CLASSIC SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES EAGLE LEVEL STAR LEVEL CART SPONSOR $2500 (1 Available) DRIVING RANGE $750 (1 Available) One foursome team Business logo on driving range signage Business logo on all carts Business logo and link on website Business logo and link on website Business logo on level sponsorship banner Mentions in social media posts Business logo on level sponsorship banner PLAYER BAG SPONSOR $500 (3 Available) Business logo on all printed marketing materials Business logo on player recognition items Business logo and link on website 2 Available) MEAL SPONSOR $1500 ( Business logo on level sponsorship banner Business logo on meal signage Business logo and link on website HOLE SPONSOR $250 (18 Available) Mentions in social media posts Business logo on tee box sign Business logo on level sponsorship banner Business logo and link on website Business logo on all printed marketing materials Business logo on level sponsorship banner Opportunity to be present at tee box LIFE LEVEL FOURSOME TEAM $600 FLAG SPONSOR $1250 (1 Available) Greens fees, 2 carts, snack bags, dinner, Business logo on flags and 2 beverages per player. -

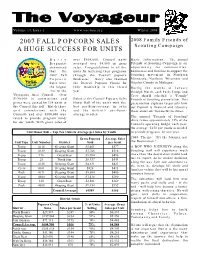

2007 Fall Popcorn Sales a Huge

Volume 14, Issue 1 www.vac-bsa.org Winter 2008 2007 FALL POPCORN SALES 2008 Family Friends of Scouting Campaign A HUGE SUCCESS FOR UNITS Barry over $604,000, Council units Basic Information: The annual Bergquist averaged over $4,500 in gross Friends of Scouting Campaign is an announced sales. Congratulations to all the opportunity for communities, that the units for bettering their programs businesses and families to support the 2007 Fall through the Council popcorn Scouting movement in Northern Popcorn fundraiser. Barry also thanked Minnesota, Northern Wisconsin and Sales were the District Popcorn Chairs for Gogebic County in Michigan. the largest their leadership in this record During the months of January ever in the year. through March, each Pack, Troop, and Voyageurs Area Council. Over Crew should schedule a "Family" $190,000 in commissions and Below is the Council Popcorn Sales Friends of Scouting presentation. This prizes were earned by 134 units in Honor Roll of the unit’s with the presentation explains to parents how the Council this fall. Match those best per -Scout-average in sales our Council is financed and educates unit commissions with the and the district’s per-Scout- them about our wonderful facilities. Council’s and over $380,000 was average in sales: The annual "Friends of Scouting" raised to provide program funds drive raises approximately 15% of the for our youth. With gross sales of Council’s operating budget each year. On average, $150 per youth is needed Unit Honor Roll – Top Ten Units in Average per Sales by Youth to provide programs for one year. -

The Council Guide

The Council Guide 2011 Edition Introduction The Council Guide Available online at www.TheCouncilGuide.com Volume 1 – Council Shoulder Insignia, councils A-L Including Red & White Strips (RWS), "Pre-CSPs", Council Shoulder Patches (CSPs), and Jamboree Shoulder Patches (JSPs) Volume 2 – Council Shoulder Insignia, councils M-Z Including Red & White Strips (RWS), "Pre-CSPs", Council Shoulder Patches (CSPs), and Jamboree Shoulder Patches (JSPs) Volume 3 – Council Shoulder Insignia, names A-L Including Community Strips (CMS), Military Base Strips (MBS), and State Strips Volume 4 – Council Shoulder Insignia, names M-Z Including Community Strips (CMS), Military Base Strips (MBS), and State Strips Volume 5 – Council Insignia, councils A-L Including Council Patches (CPs) and Council Activity Patches Volume 6 – Council Insignia, councils M-Z Including Council Patches (CPs) and Council Activity Patches Volume 7 – District Insignia, districts A-L Including District Patches and District Activity Patches Volume 8 – District Insignia, districts M-Z Including District Patches and District Activity Patches © 2011, Scouting Collectibles, LLC OVERVIEW The Council Guide attempts to catalog all Boy Scouts of America council and district insignia. Although many users may choose to only collect selected council items, The Council Guide aims to record all council insignia in order to present a more complete picture of a council’s issues. Furthermore, such a broad focus makes The Council Guide more than just another patch identification guide – The Council Guide is also a resource for individuals wishing to record and learn about the history of Scouting through its memorabilia. ORGANIZATION Since The Council Guide includes a wide variety of issues, made in different shapes and sizes and for different purposes, it can be difficult to catalog these issues in a consistent way. -

Publication 10 Part 2

Back Mountain It’s All Good News ...Covering the Back Mountain and surrounding communities! www.communitynewsonline.net Fun in the sun at JCC summer camp By: MB Gilligan Back Mountain Community News Correspondent Second, third and fourth grade girls and boys recently attended the Jewish Community Center summer camp at the Holiday House facility. The children participated in a program for their parents, grandparents, and friends recently at the camp, which included dancing to such hits as The Twist, Wipe Out, Kung Fu Fighting, Hawaiian Roller Coaster Ride and a beautiful rendition of hula dancing. Campers aged three through fourteen from throughout the Wyoming Valley have enjoyed a summer filled with typical camp activities like swimming, sports, biking, archery, and arts and crafts, as well as learning about the Jewish culture. Some of the boys who enjoyed this year’s JCC day camp are pictured with counselor Spencer Youngman. Enjoying pre-show preparations are, in front, from left: Diane Friedman, Sydney Barbini, Nia Lowe-Shaffer, Sinclaire Ogof, and Amelia Grudkowski, left, and Abby Santo, bothBuddies Cooper Wood, left, of Shavertown, and Annie Bagnall. In rear are counselors Ellen Matza and Sarah Sands. from Dallas, are dressed for the Hula Dance theyMark Hutsko, of Harvey’s Lake had a lot of fun performed at the show. together at the JCC Summer Camp. Community News • September 2010 • 2 Bear Den #3 scouts provided and served lunchDallas Lions Club installs club president to Habitat volunteers Recently, Pack 281, Bear Den #3 scouts provided and served lunch to the volunteers in Edwardsville at Habitat for Humanity. -

United States Bankruptcy Court

EXHIBIT A Exhibit A Service List Served as set forth below Description NameAddress Email Method of Service Adversary Parties A Group Of Citizens Westchester Putnam 388 168 Read Ave Tuckahoe, NY 10707-2316 First Class Mail Adversary Parties A Group Of Citizens Westchester Putnam 388 19 Hillcrest Rd Bronxville, NY 10708-4518 First Class Mail Adversary Parties A Group Of Citizens Westchester Putnam 388 39 7Th St New Rochelle, NY 10801-5813 First Class Mail Adversary Parties A Group Of Citizens Westchester Putnam 388 58 Bradford Blvd Yonkers, NY 10710-3638 First Class Mail Adversary Parties A Group Of Citizens Westchester Putnam 388 Po Box 630 Bronxville, NY 10708-0630 First Class Mail Adversary Parties Abraham Lincoln Council Abraham Lincoln Council 144 5231 S 6Th Street Rd Springfield, IL 62703-5143 First Class Mail Adversary Parties Abraham Lincoln Council C/O Dan O'Brien 5231 S 6Th Street Rd Springfield, IL 62703-5143 First Class Mail Adversary Parties Alabama-Florida Cncl 3 6801 W Main St Dothan, AL 36305-6937 First Class Mail Adversary Parties Alameda Cncl 22 1714 Everett St Alameda, CA 94501-1529 First Class Mail Adversary Parties Alamo Area Cncl#583 2226 Nw Military Hwy San Antonio, TX 78213-1833 First Class Mail Adversary Parties All Saints School - St Stephen'S Church Three Rivers Council 578 Po Box 7188 Beaumont, TX 77726-7188 First Class Mail Adversary Parties Allegheny Highlands Cncl 382 50 Hough Hill Rd Falconer, NY 14733-9766 First Class Mail Adversary Parties Aloha Council C/O Matt Hill 421 Puiwa Rd Honolulu, HI 96817 First -

Ernest Thompson Seton 1860-1946

Ernest Thompson Seton 1860-1946 Ernest Thompson Seton was born in South Shields, Durham, England but emigrated to Toronto, Ontario with his family at the age of 6. His original name was Ernest Seton Thompson. He was the son of a ship builder who, having lost a significant amount of money left for Canada to try farming. Unsuccessful at that too, his father gained employment as an accountant. Macleod records that much of Ernest Thompson Seton 's imaginative life between the ages of ten and fifteen was centered in the wooded ravines at the edge of town, 'where he built a little cabin and spent long hours in nature study and Indian fantasy'. His father was overbearing and emotionally distant - and he tried to guide Seton away from his love of nature into more conventional career paths. He displayed a considerable talent for painting and illustration and gained a scholarship for the Royal Academy of Art in London. However, he was unable to complete the scholarship (in part through bad health). His daughter records that his first visit to the United States was in December 1883. Ernest Thompson Seton went to New York where met with many naturalists, ornithologists and writers. From then until the late 1880's he split his time between Carberry, Toronto and New York - becoming an established wildlife artist (Seton-Barber undated). In 1902 he wrote the first of a series of articles that began the Woodcraft movement (published in the Ladies Home Journal). The first article appeared in May, 1902. On the first day of July in 1902, he founded the Woodcraft Indians, when he invited a group of boys to camp at his estate in Connecticut and experimented with woodcraft and Indian-style camping. -

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America There are approximately 101,135sexual abuse claims filed. Of those claims, the Tort Claimants’ Committee estimates that there are approximately 83,807 unique claims if the amended and superseded and multiple claims filed on account of the same survivor are removed. The summary of sexual abuse claims below uses the set of 83,807 of claim for purposes of claims summary below.1 The Tort Claimants’ Committee has broken down the sexual abuse claims in various categories for the purpose of disclosing where and when the sexual abuse claims arose and the identity of certain of the parties that are implicated in the alleged sexual abuse. Attached hereto as Exhibit 1 is a chart that shows the sexual abuse claims broken down by the year in which they first arose. Please note that there approximately 10,500 claims did not provide a date for when the sexual abuse occurred. As a result, those claims have not been assigned a year in which the abuse first arose. Attached hereto as Exhibit 2 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the state or jurisdiction in which they arose. Please note there are approximately 7,186 claims that did not provide a location of abuse. Those claims are reflected by YY or ZZ in the codes used to identify the applicable state or jurisdiction. Those claims have not been assigned a state or other jurisdiction. Attached hereto as Exhibit 3 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the Local Council implicated in the sexual abuse.