GIRL SCOUT RANGER 19Th Amendment Centennial Patch Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 19Th Amendment

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Women Making History: The 19th Amendment Women The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. —19th Amendment to the United States Constitution In 1920, after decades of tireless activism by countless determined suffragists, American women were finally guaranteed the right to vote. The year 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. It was ratified by the states on August 18, 1920 and certified as an amendment to the US Constitution on August 26, 1920. Developed in partnership with the National Park Service, this publication weaves together multiple stories about the quest for women’s suffrage across the country, including those who opposed it, the role of allies and other civil rights movements, who was left behind, and how the battle differed in communities across the United States. Explore the complex history and pivotal moments that led to ratification of the 19th Amendment as well as the places where that history happened and its continued impact today. 0-31857-0 Cover Barcode-Arial.pdf 1 2/17/20 1:58 PM $14.95 ISBN 978-1-68184-267-7 51495 9 781681 842677 The National Park Service is a bureau within the Department Front cover: League of Women Voters poster, 1920. of the Interior. It preserves unimpaired the natural and Back cover: Mary B. Talbert, ca. 1901. cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this work future generations. -

Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: the President and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment Beth Behn University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected]

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Open Access Dissertations 2-2012 Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: The President and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment Beth Behn University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Behn, Beth, "Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: The rP esident and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment" (2012). Open Access Dissertations. 511. https://doi.org/10.7275/e43w-h021 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations/511 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WOODROW WILSON’S CONVERSION EXPERIENCE: THE PRESIDENT AND THE FEDERAL WOMAN SUFFRAGE AMENDMENT A Dissertation Presented by BETH A. BEHN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2012 Department of History © Copyright by Beth A. Behn 2012 All Rights Reserved WOODROW WILSON’S CONVERSION EXPERIENCE: THE PRESIDENT AND THE FEDERAL WOMAN SUFFRAGE AMENDMENT A Dissertation Presented by BETH A. BEHN Approved as to style and content by: _________________________________ Joyce Avrech Berkman, Chair _________________________________ Gerald Friedman, Member _________________________________ David Glassberg, Member _________________________________ Gerald McFarland, Member ________________________________________ Joye Bowman, Department Head Department of History ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would never have completed this dissertation without the generous support of a number of people. It is a privilege to finally be able to express my gratitude to many of them. -

Contents Part A. Part B. B 1. Oppression, 1776

CO NTENTS PART A . PART B . O RESSION 1 7 6 - 1 6 1 . 7 8 5 B PP , RE ONSTR TI N RE RES I 1 - 1 B2 . O S ON 865 900 C UC P , B3 REKINDLIN CIVIL RI TS 1 900 -1 94 1 . G GH , B4 IRT OF THE IVIL RI TS MOVEMENT 1 4 - . 9 1 1 954 B H C GH , B MODERN IVIL RI TS MOVEMENT 1 955 - 1 5 . 964 C GH , B THE SE OND REV L I N 1 - 1 6 . O T O 965 976 C U , PART C . 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ART D DETERMINATIONS OF SITE SI NIFI AN E P . G C C EVALUATING THE SIGNIFICANCE OF SITES T E I LIO RAP Y PAR . B B G H SOURCES CONSULTED RECOMMENDED READIN G ONS LTIN I STORIANS PART F . C U G H LIST OF TABLES NATIONAL ARK SERVI E IV IL RI TS RELATED INTER RETATION TA BLE 1 . -

Parades, Pickets, and Prison: Alice Paul and the Virtues of Unruly Constitutional Citizenship

PARADES, PICKETS, AND PRISON: ALICE PAUL AND THE VIRTUES OF UNRULY CONSTITUTIONAL CITIZENSHIP Lynda G. Dodd* INTRODUCTION: MODELS OF CONSTITUTIONAL CITIZENSHIP For all the recent interest in “popular constitutionalism,” constitutional theorists have devoted surprisingly little attention to the habits and virtues of citizenship that constitutional democracies must cultivate, if they are to flourish.1 In my previous work, I have urged scholars of constitutional politics to look beyond judicial review and other more traditional checks and balances intended to prevent governmental misconduct, in order to examine the role of “citizen plaintiffs”2 – individuals who, typically at great personal cost in a legal culture where the odds are stacked against them, attempt to enforce their rights in * 1 For some exceptions, see Walter F. Murphy, CONSTITUTIONAL DEMOCRACY: CREATING AND MAINTAINING A JUST POLITICAL ORDER (2007); JAMES E. FLEMING, SECURING CONSTITUTIONAL DEMOCRACY: THE CASE FOR AUTONOMY (2006); Wayne D. Moore, Constitutional Citizenship in CONSTITUTIONAL POLITICS: ESSAYS ON CONSTITUTIONAL MAKING, MAINTENANCE, AND CHANGE (Sotirios A. Barber and Robert P. George, eds. 2001); Paul Brest, Constitutional Citizenship, 34 CLEV. ST. L. REV. 175 (1986). 2 Under this model of citizenship, the citizen plaintiff is participating in the process of constitutional checks and balances. That participation can be described in terms of “enforcing” constitutional norms or “protesting” the government’s departure from them. The phrase “private attorneys general” is the traditional term used to describe citizen plaintiffs. See, e.g., David Luban, Taking Out the Adversary: The Assault on Progressive Public Interest Lawyers, 91 CAL. L. REV. 209 (2003); Pamela Karlan, Disarming the Private Attorney General, 2003 U. -

Helping Women to Recover: Creating Gender-Specific Treatment for Substance-Abusing Women and Girls in Community Correctional Settings

Helping Women to Recover: Creating Gender-Specific Treatment for Substance-Abusing Women and Girls in Community Correctional Settings Stephanie S. Covington, Ph.D., LCSW Co-Director, Center for Gender and Justice La Jolla, California Presented at: International Community Corrections Association Arlington, Virginia 1998 Published in: In M. McMahon, ed., Assessment to Assistance: Programs for Women in Community Corrections. Latham, Md.: American Correctional Association, 2000, 171-233. Some of the most neglected and misunderstood women and girls in North America are those in the criminal justice system. Largely because of the “War on Drugs,” the rate of incarceration for women in the United States has tripled since 1980 (Bloom , Chesney- Lind, & Owen., 1994; Collins & Collins, 1996). Between 1986 and 1991, the number of women in state prisons for drug-related offenses increased by 432 percent (Phillips & Harm, 1998). Like their juvenile counterparts, most of these women are non-violent offenders who could be treated much more effectively and economically in community- based gender-specific programs. When females are not a security risk, community-based sanctions offer benefits to society, to female offenders1 themselves, and to their children. One survey compares an $869 average annual cost for probation to $14,363 for jail and $17,794 for prison (Phillips & Harm, 1998). Community corrections disrupt females’ lives less than does incarceration and subject them to less isolation. Further, community corrections potentially disrupt the lives of children far less. Unfortunately, few drug treatment programs exist that address the needs of females, especially those with minor children. This is unfortunate because, when allied with probation, electronic monitoring, community service, and/or work release, community-based substance abuse treatment could be an effective alternative to the spiraling rates of recidivism and re-incarceration. -

NJWV-Public-Programs-Toolkit.Pdf

a. Vision b. Goals c. NJ Women Vote Partners a. Big Ideas to Consider b. Building Partnerships c. How to Use the Toolkit a. Make b. Perform c. Watch d. Read e. Exhibit f. Speak g. Remember h. March i. Vote j. Commemorate This multi-faceted programming initiative, launching in 2020, will mark 100 years of women’s suffrage in the United States. To prepare for NJ Women Vote, the New Jersey Historical Commission, in collaboration with the Alice Paul Institute, has gathered over 70 partners across New Jersey, representing history and cultural organizations, women’s groups, government agencies, libraries, and higher education institutions. Together, partners are planning a yearlong series of events, programs, and projects across the state to mark the centennial. Vision To mark the centennial of women’s suffrage while acknowledging its inequities and the challenges New Jersey women of all backgrounds have faced and continue to confront from 1920 to the present day. Goals ● Tell the true story of suffrage ● Engage the widest possible audience ● Encourage civic participation through voting ● Develop programs that result in change NJ Women Vote Partners Visit the NJ Women Vote website for a full list of partner organizations. Would you like to become a partner? NJ Women Vote partners are organizations or individuals interested in planning projects and programs to mark the suffrage centennial. There is no financial or time commitment to become a partner. We encourage partners to attend the initiative’s quarterly meetings and participate on committees and subcommittees. Please contact [email protected] to learn more about the partnership. -

Institutionalizing the Pennsylvania System: Organizational Exceptionalism, Administrative Support, and Eastern State Penitentiary, 1829–1875

Institutionalizing the Pennsylvania System: Organizational Exceptionalism, Administrative Support, and Eastern State Penitentiary, 1829–1875 By Ashley Theresa Rubin A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Jurisprudence and Social Policy in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Malcolm Feeley, Chair Professor Cybelle Fox Professor Calvin Morrill Professor Jonathan Simon Spring 2013 Copyright c 2013 Ashley Theresa Rubin All rights reserved Abstract Institutionalizing the Pennsylvania System: Organizational Exceptionalism, Administrative Support, and Eastern State Penitentiary, 1829–1875 by Ashley Theresa Rubin Doctor of Philosophy in Jurisprudence and Social Policy University of California, Berkeley Professor Malcolm Feeley, Chair I examine the puzzling case of Eastern State Penitentiary and its long-term retention of a unique mode of confinement between 1829 and 1875. Most prisons built in the nineteenth cen- tury followed the “Auburn System” of congregate confinement in which inmates worked daily in factory-like settings and retreated at night to solitary confinement. By contrast, Eastern State Penitentiary (f. 1829, Philadelphia) followed the “Pennsylvania System” of separate confinement in which each inmate was confined to his own cell for the duration of his sentence, engaging in workshop-style labor and receiving religious ministries, education, and visits from selected person- nel. Between 1829 and the 1860s, Eastern faced strong pressures to conform to field-wide norms and adopt the Auburn System. As the progenitor of the Pennsylvania System, Eastern became the target of a debate raging over the appropriate model of “prison discipline.” Supporters of the Auburn System (penal reformers and other prisons’ administrators) propagated calumnious myths, arguing that the Pennsylvania System was cruel and inhumane, dangerous to inmates’ physical and mental health, too expensive, and simply impractical and ineffective. -

Madonna... Who Cares ?

THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S Q 1 ON THE Vol. XXVI SPRING 1993 $3.95 RUSSIAN OMEN: MADONNA... EX AFTER WHO CARES ? THE FALL BEYOND "CHOICE"- CONTROYERSIES IN WOMEN'S HEALTH ELAYNE RAPPING ON WOODY ALLEN; MIA FARROW " pt. Women rs History is Worth Saving Help Preserve Paulsdale In 1923, Alice Paul authored the Equal We know the importance of public Rights Amendment and crusaded for its pas- memoriakThey serve as symbols of our sage for the rest of her life. She also wrote the «>lle«ive past and inspirations for our equalrightsstatementsintheUnitedNations futurc- ^ there are few national monu- Charter Because of Alice Paul's work, the ments wluch KCO&™ the contributions of 1964CivilRightsActoutlawedsexdiscrimi- Amencan women. Although women sparked " B . the historic preservation movement in this nation m the workplace. m Qn[y A% of al, Natbnal Historic Today, the Alice Paul Centennial Foun- i^fa^ honor the accomplishments of dation, a volunteer, not-for-profit organiza- women> tion, is struggling to preserve Paulsdale, her Women pionecred major reforms in edu- birthplace and home. cation, health care, labor and many other Paulsdale, recently named a National His- areas of our society. Paulsdale will become a Alice Stokes Paul toric Landmark, is acirca 1840 farmhouse on national leadership center where new (1885 - 1977) 6.5 acres in Mount Laurel, New Jersey, near generations of women and girls will come Philadelphia. This is the place where Alice together to create solutions to the problems voices throughout the land, re- peating oaths of office for the Cabinet, the To honor the vision and courage of Alice Paul, the Foundation plans to create at seizing this opportunity to preserve Paulsdale Senate, the House and for state and local as a place to help create a positive future for offices. -

Becoming a Detective: Historical Case File #5—Prisoners and Hunger

Becoming a Detective: Historical Case peacefully exercising their right to petition their File #5—Prisoners and Hunger Strikes government. Because they believed themselves to be political prisoners, the women refused to At the request of the textbook committee your cooperate with their jailors. class has been asked to investigate whether Hazel Hunkins deserves to be included in the According to an article published on the website next edition of the textbook. This case cannot American Memory, the imprisoned women were be solved without an understanding of the “sometimes beaten (most notably during the National Woman’s Party’s decision to com- November 15 “Night of Terror” at Occoquan mit civil disobedience, their demands to be Workhouse), and often brutally force-fed when treated as political prisoners, and the attention they went on hunger strikes to protest being their imprisonment brought to the cause. As a denied political prisoner status. Women of all member of the commission selected to review classes risked their health, jobs, and reputations the case, your job is to examine the following by continuing their protests. One historian documents to better understand the why these estimated that approximately 2,000 women women decided to break the law and what af- spent time on the picket lines between 1917 fect their actions had. and 1919, and that 500 women were arrested, of whom 168 were actually jailed. The NWP • Why did suffrage prisoners consider made heroes of the suffrage prisoners, held themselves to be political prisoners? Do you ceremonies in their honor, and presented them agree with their claim? with commemorative pins. -

'I Want to Go to Jail': the Woman's Party

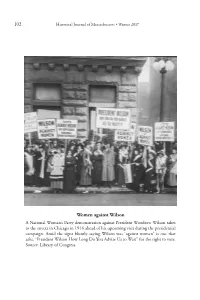

102 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2017 Women against Wilson A National Woman’s Party demonstration against President Woodrow Wilson takes to the streets in Chicago in 1916 ahead of his upcoming visit during the presidential campaign. Amid the signs bluntly saying Wilson was “against women” is one that asks, “President Wilson How Long Do You Advise Us to Wait” for the right to vote. Source: Library of Congress. 103 “I Want to Go to Jail”: The Woman’s Party Reception for President Wilson in Boston, 1919 JAMES J. KENNEALLY Abstract: Agitation by the National Woman’s Party (NWP) was but one of several factors leading to the successful passage of the Nineteenth Amendment and woman suffrage. By turning to direct action, concentrating on a federal amendment, and courting jail sentences (unlike the more restrained National American Woman Suffrage Association), they obtained maximum publicity for their cause even when, as in Boston, their demonstration had little direct bearing on enfranchisement. Although historians have amply documented the NWP’s vigils and arrests before the White House, the history of the Massachusetts chapter of the NWP and the story of their demonstrations in Boston in 1919 has been mostly overlooked. This article gives these pioneering suffragists their recognition. Nationally, the only women to serve jail sentences on behalf of suffrage were the 168 activists arrested in the District of Columbia and the sixteen women arrested in Boston. Dr. James J. Kenneally, a Professor Emeritus and former Director of Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Vol. 45 (1), Winter 2017 © Institute for Massachusetts Studies, Westfield State University 104 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2017 the Martin Institute at Stonehill College, has written extensively on women’s history.1 * * * * * * * Alice Paul (1885–1977) and Lucy Burns (1879–1966) met in jail in 1909 in England. -

The Fifteenth Star: Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party in Minnesota

The Fifteenth Star Alice Paul and the National Woman’s Party in Minnesota J. D. Zahniser n June 3, 1915, Alice Paul hur- Oriedly wrote her Washington headquarters from the home of Jane Bliss Potter, 2849 Irving Avenue South, Minneapolis: “Have had con- ferences with nearly every Suffragist who has ever been heard of . in Minnesota. Have conferences tomor- row with two Presidents of Suffrage clubs. I do not know how it will come out.”1 Alice Paul came to Minnesota in 1915 after Potter sought her help in organizing a Minnesota chapter of the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (CU). The CU was a new- comer on the national suffrage scene, founded by Paul in 1913. She focused on winning a woman suffrage amend- ment to the US Constitution. Paul, a compelling— even messianic— personality, riveted attention on a constitutional amendment long Alice Paul, 1915. before most observers considered it viable; she also practiced more frage Association (MWSA), had ear- she would not do. I have spent some assertive tactics than most American lier declined to approve a Minnesota hours with her.”3 suffragists thought wise.2 CU chapter; MWSA president Clara After Paul’s visit, Ueland and the Indeed, the notion of Paul coming Ueland had personally written Paul to MWSA decided to work cooperatively to town apparently raised suffrage discourage a visit. Nonetheless, once with the Minnesota CU; their collabo- hackles in the Twin Cities. Paul wrote Paul arrived in town, she reported ration would prove a marked contrast from Minneapolis that the executive that Ueland “has been very kind and to the national scene. -

The Centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment

Sarah Jane Corson Downs, Ocean Grove Audiences listened with rapt attention when Sarah Downs, a social reformer with a booming voice and daunting appearance, condemned alcohol as “the enemy.” As previously mentioned, Downs became president of the New Jersey Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) in 1881. Despite her tough demeanor, “Mother Downs” was The Monmouth County Clerk’s Office kind and loving. commemorates Sarah was born in 1822 to an old Philadelphia family, members of the Dutch Reformed Church. When she was five, her father died and, in The Centennial of the the 1830s, her widowed mother moved the family to New Jersey, initially in Pennington. Sarah experienced “a conversion” at seventeen and became an Evangelical Methodist. While teaching school in New Nineteenth Amendment Egypt, she met a widower, Methodist circuit minister Rev. Charles S. Downs. After they married in 1850, Sarah left teaching and cared for their children. When Rev. Downs retired for health reasons, the family relocated to Tuckerton. To make ends meet, Sarah resumed teaching and wrote newspaper articles. After Rev. Downs died in 1870, she raised funds for a new church and became increasingly interested in women’s welfare. In the mid-1870s, Downs moved to Ocean Grove, the dry Methodist seaside town that would become known for its women activists and entrepreneurs. In 1882, she purchased a house lease at 106 Mount Tabor Way for $490. During her Ocean Grove years, Downs significantly increased the WCTU membership. Loyal to Frances Willard, national WCTU president, Downs supported suffrage as “a means for women to better protect their homes and children” and to help achieve the prohibition of alcohol.