Early Germanic Preposition Stranding Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concepts and Methods of Historical Linguistics-The Germanic Family Of

CURSO 2016 - 2017 CONCEPTS AND METHODS OF HISTORICAL LINGUISTICS Tutor: Carlos Hernández Simón Sir William Jones, Jacob Grimm and Karl Verner from Lisa Minnick 2011: “Let them eat metaphors, Part 1: Order from Chaos and the Indo-European Hypothesis” Functional Shift https://functionalshift.wordpress.com/2011/10/09/metaphors1/ [retrieved February 17, 2017] CONCEPTS AND METHODS OF HISTORICAL LINGUISTICS HISTORICAL AND COMPARATIVE LINGUISTICS AIMS OF STUDY 1) Language change and stability 2) Reconstruction of earlier stages of languages 3) Discovery and implementation of research methodologies Theodora Bynon (1981) 1) Grammars that result from the study of different time spans in the evolution of a language 2) Contrast them with the description of other related languages 3) Linguistic variation cannot be separated from sociological and geographical factors 3 CONCEPTS AND METHODS OF HISTORICAL LINGUISTICS ORIGINS • Renaissance: Contrastive studies of Greek and Latin • Nineteenth Century: Sanskrit 1) Acknowledgement of linguistic change 2) Development of the Comparative Method • Robert Beekes (1995) 1) The Greeks 2) Languages Change • R. Lawrence Trask (1996) 1) 6000-8000 years 2) Historical linguist as a kind of archaeologist 4 CONCEPTS AND METHODS OF HISTORICAL LINGUISTICS THE COMPARATIVE METHOD • Sir William Jones (1786): Greek, Sanskrit and Latin • Reconstruction of Proto-Indo-European • Regular principle of phonological change 1) The Neogrammarians 2) Grimm´s Law (1822) and Verner’s Law (1875) 3) Laryngeal Theory : Ferdinand de Saussure (1879) • Two steps: 1) Isolation of a set of cognates: Latin: decem; Greek: deca; Sanskrit: daśa; Gothic: taihun 2) Phonological correspondences extracted: 1. Latin d; Greek d; Sanskrit d; Gothic t 2. Latin e; Greek e; Sanskrit a; Gothic ai 3. -

Internal Classification of Indo-European Languages: Survey

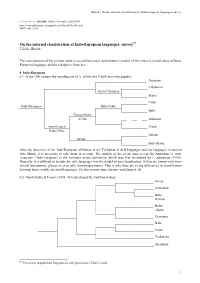

Václav Blažek (Masaryk University of Brno, Czech Republic) On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: Survey The purpose of the present study is to confront most representative models of the internal classification of Indo-European languages and their daughter branches. 0. Indo-European 0.1. In the 19th century the tree-diagram of A. Schleicher (1860) was very popular: Germanic Lithuanian Slavo-Lithuaian Slavic Celtic Indo-European Italo-Celtic Italic Graeco-Italo- -Celtic Albanian Aryo-Graeco- Greek Italo-Celtic Iranian Aryan Indo-Aryan After the discovery of the Indo-European affiliation of the Tocharian A & B languages and the languages of ancient Asia Minor, it is necessary to take them in account. The models of the recent time accept the Anatolian vs. non-Anatolian (‘Indo-European’ in the narrower sense) dichotomy, which was first formulated by E. Sturtevant (1942). Naturally, it is difficult to include the relic languages into the model of any classification, if they are known only from several inscriptions, glosses or even only from proper names. That is why there are so big differences in classification between these scantily recorded languages. For this reason some scholars omit them at all. 0.2. Gamkrelidze & Ivanov (1984, 415) developed the traditional ideas: Greek Armenian Indo- Iranian Balto- -Slavic Germanic Italic Celtic Tocharian Anatolian 0.3. Vladimir Georgiev (1981, 363) included in his Indo-European classification some of the relic languages, plus the languages with a doubtful IE affiliation at all: Tocharian Northern Balto-Slavic Germanic Celtic Ligurian Italic & Venetic Western Illyrian Messapic Siculian Greek & Macedonian Indo-European Central Phrygian Armenian Daco-Mysian & Albanian Eastern Indo-Iranian Thracian Southern = Aegean Pelasgian Palaic Southeast = Hittite; Lydian; Etruscan-Rhaetic; Elymian = Anatolian Luwian; Lycian; Carian; Eteocretan 0.4. -

Gothic Introduction – Part 1: Linguistic Affiliations and External History Roadmap

RYAN P. SANDELL Gothic Introduction – Part 1: Linguistic Affiliations and External History Roadmap . What is Gothic? . Linguistic History of Gothic . Linguistic Relationships: Genetic and External . External History of the Goths Gothic – Introduction, Part 1 2 What is Gothic? . Gothic is the oldest attested language (mostly 4th c. CE) of the Germanic branch of the Indo-European family. It is the only substantially attested East Germanic language. Corpus consists largely of a translation (Greek-to-Gothic) of the biblical New Testament, attributed to the bishop Wulfila. Primary manuscript, the Codex Argenteus, accessible in published form since 1655. Grammatical Typology: broadly similar to other old Germanic languages (Old High German, Old English, Old Norse). External History: extensive contact with the Roman Empire from the 3rd c. CE (Romania, Ukraine); leading role in 4th / 5th c. wars; Gothic kingdoms in Italy, Iberia in 6th-8th c. Gothic – Introduction, Part 1 3 What Gothic is not... Gothic – Introduction, Part 1 4 Linguistic History of Gothic . Earliest substantively attested Germanic language. • Only well-attested East Germanic language. The language is a “snapshot” from the middle of the 4th c. CE. • Biblical translation was produced in the 4th c. CE. • Some shorter and fragmentary texts date to the 5th and 6th c. CE. Gothic was extinct in Western and Central Europe by the 8th c. CE, at latest. In the Ukraine, communities of Gothic speakers may have existed into the 17th or 18th century. • Vita of St. Cyril (9th c.) mentions Gothic as a liturgical language in the Crimea. • Wordlist of “Crimean Gothic” collected in the 16th c. -

Adverbial Reinforcement of Demonstratives in Dialectal German

Glossa a journal of general linguistics Adverbial reinforcement of COLLECTION: NEW PERSPECTIVES demonstratives in dialectal ON THE NP/DP DEBATE German RESEARCH PHILIPP RAUTH AUGUSTIN SPEYER *Author affiliations can be found in the back matter of this article ABSTRACT CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Philipp Rauth In the German dialects of Rhine and Moselle Franconian, demonstratives are Universität des Saarlandes, reinforced by locative adverbs do/lo ‘here/there’ in order to emphasize their deictic Germany strength. Interestingly, these adverbs can also appear in the intermediate position, i.e., [email protected] between the demonstrative and the noun (e.g. das do Bier ‘that there beer’), which is not possible in most other varieties of European German. Our questionnaire study and several written and oral sources suggest that reinforcement has become mandatory in KEYWORDS: demonstrative contexts. We analyze this grammaticalization process as reanalysis of demonstrative; reinforcer; do/lo from a lexical head to the head of a functional Index Phrase. We also show that a German; Rhine Franconian; functional DP-shell can better cope with this kind of syntactic change and with certain Moselle Franconian; Germanic; serialization facts concerning adjoined adjectives. Romance; dialectal German; grammaticalization; reanalysis; NP; DP; questionnaire TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Rauth, Philipp and Augustin Speyer. 2021. Adverbial reinforcement of demonstratives in dialectal German. Glossa: a journal of general linguistics 6(1): 4. 1–24. DOI: https://doi. org/10.5334/gjgl.1166 1 INTRODUCTION Rauth and Speyer 2 Glossa: a journal of In colloquial Standard German, the only difference between definite determiners (1a) and general linguistics DOI: 10.5334/gjgl.1166 demonstratives is emphatic stress in demonstrative contexts (1b). -

A Concise History of English a Concise Historya Concise of English

A Concise History of English A Concise HistoryA Concise of English Jana Chamonikolasová Masarykova univerzita Brno 2014 Jana Chamonikolasová chamonikolasova_obalka.indd 1 19.11.14 14:27 A Concise History of English Jana Chamonikolasová Masarykova univerzita Brno 2014 Dílo bylo vytvořeno v rámci projektu Filozofická fakulta jako pracoviště excelentního vzdě- lávání: Komplexní inovace studijních oborů a programů na FF MU s ohledem na požadavky znalostní ekonomiky (FIFA), reg. č. CZ.1.07/2.2.00/28.0228 Operační program Vzdělávání pro konkurenceschopnost. © 2014 Masarykova univerzita Toto dílo podléhá licenci Creative Commons Uveďte autora-Neužívejte dílo komerčně-Nezasahujte do díla 3.0 Česko (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 CZ). Shrnutí a úplný text licenčního ujednání je dostupný na: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/cz/. Této licenci ovšem nepodléhají v díle užitá jiná díla. Poznámka: Pokud budete toto dílo šířit, máte mj. povinnost uvést výše uvedené autorské údaje a ostatní seznámit s podmínkami licence. ISBN 978-80-210-7479-8 (brož. vaz.) ISBN 978-80-210-7480-4 (online : pdf) ISBN 978-80-210-7481-1 (online : ePub) ISBN 978-80-210-7482-8 (online : Mobipocket) Contents Preface ....................................................................................................................4 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................5 Abbreviations and Symbols ...................................................................................6 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................7 -

Vocalisations: Evidence from Germanic Gary Taylor-Raebel A

Vocalisations: Evidence from Germanic Gary Taylor-Raebel A thesis submitted for the degree of doctor of philosophy Department of Language and Linguistics University of Essex October 2016 Abstract A vocalisation may be described as a historical linguistic change where a sound which is formerly consonantal within a language becomes pronounced as a vowel. Although vocalisations have occurred sporadically in many languages they are particularly prevalent in the history of Germanic languages and have affected sounds from all places of articulation. This study will address two main questions. The first is why vocalisations happen so regularly in Germanic languages in comparison with other language families. The second is what exactly happens in the vocalisation process. For the first question there will be a discussion of the concept of ‘drift’ where related languages undergo similar changes independently and this will therefore describe the features of the earliest Germanic languages which have been the basis for later changes. The second question will include a comprehensive presentation of vocalisations which have occurred in Germanic languages with a description of underlying features in each of the sounds which have vocalised. When considering phonological changes a degree of phonetic information must necessarily be included which may be irrelevant synchronically, but forms the basis of the change diachronically. A phonological representation of vocalisations must therefore address how best to display the phonological information whilst allowing for the inclusion of relevant diachronic phonetic information. Vocalisations involve a small articulatory change, but using a model which describes vowels and consonants with separate terminology would conceal the subtleness of change in a vocalisation. -

3 Proto-Germanic

A CONCISE HISTORY OF ENGLISH 3 Proto-Germanic 3.1 The common ancestor of Germanic languages Proto-Germanic, also referred to as Primitive Germanic, Common Germanic, or Ur- Germanic, is one of the descendants of Proto-Indo-European and the common ancestor of all Germanic languages. Th is Germanic proto-language, which was reconstructed by the comparative method, is not attested by any surviving texts. Th e only written records available are the runic Vimose inscriptions from around 200 AD found in Denmark, which represent an early stage of Proto-Norse or Late Proto-Germanic. (Comrie 1987) Proto-Germanic is assumed to have developed between about 500 BC and the be- ginning of the Common Era. (Ringe 2006, p. 67). It came aft er the First Germanic Sound Shift , which was probably contemporary with the Nordic Bronze Age. Th e pe- riod between the end of Proto-Indo-European (i.e. probably aft er 3 500 BC) and the beginning of Proto-Germanic (500 BC) is referred to as Pre-Proto-Germanic period. However, Pre-Proto-Germanic is sometimes included under the wider meaning of Proto- Germanic, and the notion of the Germanic parent language is used to refer to both stages. Th e First Germanic Sound Shift , also known as Grimm’s law or Rask’s rule, is a chain shift of Proto-Indo-European stops which took place between the Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Germanic stage of development and which distinguishes Germanic lan- guages from other Indo-European centum languages. Grimm’s law, together with a relat- ed shift entitled Verner’s law, is described in greater detail in Chapter 7. -

A Linguistic History of English, Vol. 2. by DON RINGE and ANN TAYLOR. Oxford

REVIEWS 741 guistics (subsense units, hyponymy and meronymy, antonymy), whereas Dąbrowska 2004 sees cognitive linguistics mostly from the perspective of acquisition and gives a general orientation to the field only in Ch . 1 0. By contrast, Evans & Green 2006 is relatively comprehensive and specif - ically designed as a textbook, but intimidating in its bulk (over 800 pages). Given these alterna - tives, if one needs an introduction to cognitive linguistics in general or L’s work in particular, this book is an attractive candidate. REFERENCES Croft, William , and D. Alan Cruse . 2004. Cognitive linguistics . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. D browska, Ewa Ą . 2004. Language, mind and brain . Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. Evans, Vyvyan , and Melanie Green . 2006. Cognitive linguistics: An introduction . Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Langacker, Ronald W . 1987 . Foundations of cognitive grammar, vol. 1: Theoretical prerequisites . Stan - ford, CA: Stanford University Press. Langacker, Ronald W . 1991a . Foundations of cognitive grammar, vol. 2: Descriptive application . Stan - ford, CA: Stanford University Press. Langacker, Ronald W . 1991b. Concept, image, and symbol . Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Langacker, Ronald W . 2000. Grammar and conceptualization. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Langacker, Ronald W . 2008 . Cognitive grammar: A basic introduction . Oxford: Oxford University Press. Taylor, John R . 2002. Cognitive grammar . Oxford: Oxford University Press. Ungerer, Friedrich , and Hans-Jorg Schmid . 1996. An introduction to cognitive linguistics . London: Longman. HSL fakultet, UiT 9037 Tromsø, Norway [[email protected]] The development of Old English: A linguistic history of English, vol. 2. By Don Ringe and Ann Taylor . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014. Pp. ix, 614. ISBN 9780199207848. $135 (Hb). -

Het Noordzeegermaanse Vraagstuk Schiepen Een Volmaakt Kader Om Toch Nog Eens Een Poging Te Doen Om Meer Klaarheid Te Scheppen Over “Dat Verdraaide Ingveoons”!

2009 – 2010 Het Noor dzeegermaans: Een status questionis Verhandeling voorgelegd aan de Faculteit Letteren en Wijsbegeerte voor het verkrijgen van de graad van Master in de Historische Taal- en Letterkunde door Alexander Demoor Promotor: Prof. Dr. Luc De Grauwe 2 Dankwoord Ik wens prof. dr. De Grauwe uit de grond van mijn hart te bedanken voor de schier oneindige (!) bereidwilligheid tot nuttige raadgevingen en opbouwende commentaar die hij aan de dag legde tijdens het schrijven van deze verhandeling. Zonder de overweldigende hoeveelheid aan relevante en fascinerende bronnen die hij mij, een verstokt pendelstudent, op de meest uiteenlopende wijzen bezorgde, was dit alles nooit tot stand gekomen. Eveneens wil ik mevr. Rottier van de vakgroep Duitse Taalkunde alsook mevr. Willems en mevr. Bouckaert van de vakgroep Nederlandse Taalkunde bedanken voor hun soepelheid ten opzichte van het ontleningssysteem van de Gentse Universiteitsbibliotheken en vooral de vriendelijke hulp die mij werd gegeven toen ik weer eens de weg naar het juiste boek zoek was. Ik druk bij deze ook de oprechte waardering uit voor de algemene steun van mijn ouders tijdens dit uitdagende en erg intensieve studiejaar, en het geduld en begrip dat zij opbrachten voor de mindere dagen. Dit dankwoord is ook gericht aan de kameraden, zowel mannelijk als vrouwelijk, die mij inspiratie verleenden tijdens het schrijfproces en af en toe wat verstrooiing boden. Vooral de begeesterende gesprekken met dhr. Krekelbergh over het archeologische aspect van het Noordzeegermaanse vraagstuk schiepen een volmaakt kader om toch nog eens een poging te doen om meer klaarheid te scheppen over “dat verdraaide Ingveoons”! 3 4 Inhoudsopgave Dankwoord - 3 - Inhoudsopgave - 5 - 1. -

The Grouping of the Germanic Languages: a Critical Review Michael-Christopher Todd Highlander University of South Carolina - Columbia

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2014 The Grouping of the Germanic Languages: A Critical Review Michael-Christopher Todd Highlander University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the German Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Highlander, M. T.(2014). The Grouping of the Germanic Languages: A Critical Review. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/2587 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Grouping of the Germanic Languages: A Critical Review by Michael-Christopher Todd Highlander Bachelor of Arts University of Virginia, 2012 ______________________________ Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in German College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2014 Accepted by: Kurt Goblirsch, Director of Thesis Yvonne Ivory, Reader Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Abstract The literature regarding the grouping of the Germanic languages will be reviewed and a potential solution to the problems of the division of the Germanic languages will be proposed. Most of the Germanic languages share a great number of similarities, and individual languages often have features common to more than one which complicates the grouping. The grouping of the Germanic languages has been debated by linguists since the 19th century, and there are still dissenting views on this topic. Old English, Old Low Franconian and Old Saxon pose significant issues with regard to grouping, and the research for this thesis will attempt to clarify where these languages fit with other Germanic languages and what the best classification of the Germanic languages would be. -

The Emergence of the Germanic Languages in Northern Europe

07/08/18 1 The Emergence of the Germanic Languages in Northern Europe Seán Vrieland Den Arnamagnæanske Samling Københavns Universitet 9 August 2018 Germanic in Popular Culture Indo-European Languages by number of speakers today Rank Language Total Speakers Native Speakers 1 English 1.12 billion 378.2 million 2 Hindustani 679.4 million 329.1 million 3 Spanish 512.9 million 442.3 million 4 French 284.9 million 76.7 million 5 Russian 264.3 million 153.9 million 6 Bengali 261.8 million 242.6 million 7 Portuguese 236.5 million 222.7 million 8 Punjabi 148.3 million 148.3 million 9 German 132 million 76 million 10 Persian 110 million 60 million Modern Germanic languages by native speakers Language Native Speakers West Germanic English 378 million German 76 million Dutch 22 million Afrikaans 7 million Frisian 0.5 million North Germanic Swedish 10 million Danish 6 million Norwegian 5 million Icelandic 350 000 Faroese 66 000 A (Simplified) Family Tree Proto-Germanic West North East OE OFr ODu OS OHG OWN OEN †Goth En Fr Du LGm Gm Icel Far Nor Da Sw Afr The Early Days of Germanic Figure: Distribution of Proto-Germanic ca. 500 BC. Wikimedia Commons Why Germanic? The Race to the Roots Figure: The Silver Bible (Codex Argenteus) containing the Gothic translation. ©Uppsala University Library Peder Syv (1663): Some Thoughts on the Cimbric (Danish) Language Should we see how various languages largely correspond with each other, then we cannot help but wonder about it. In Hebrew, Greek, and Latin (without even comparing them to each other) are many words and ways of speaking which resemble our speech. -

Blažek : on the Internal Classification of Indo-European Languages: Survey

Blažek : On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey Linguistica ONLINE. Added: November 22nd 2005. http://www.phil.muni.cz/linguistica/art/blazek/bla-003.pdf ISSN 1801-5336 On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey[*] Václav Blažek The main purpose of the present study is to confront most representative models of the internal classification of Indo- European languages and their daughter branches. 0. Indo-European 0.1. In the 19th century the tree-diagram of A. Schleicher (1860) was very popular: Germanic Lithuanian Slavo-Lithuaian Slavic Celtic Indo-European Italo-Celtic Italic Graeco-Italo- -Celtic Albanian Aryo-Graeco- Greek Italo-Celtic Iranian Aryan Indo-Aryan After the discovery of the Indo-European affiliation of the Tocharian A & B languages and the languages of ancient Asia Minor, it is necessary to take them in account. The models of the recent time accept the Anatolian vs. non- Anatolian (‘Indo-European’ in the narrower sense) dichotomy, which was first formulated by E. Sturtevant (1942). Naturally, it is difficult to include the relic languages into the model of any classification, if they are known only from several inscriptions, glosses or even only from proper names. That is why there are so big differences in classification between these scantily recorded languages. For this reason some scholars omit them at all. 0.2. Gamkrelidze & Ivanov (1984, 415) developed the traditional ideas: Greek Armenian Indo- Iranian Balto- -Slavic Germanic Italic Celtic Tocharian Anatolian [*] Previously unpublished. Reproduced with permission. [Editor’s note] 1 Blažek : On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey 0.3.