The Urinary Tract and Adrenal Glands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Educational Paper Ciliopathies

Eur J Pediatr (2012) 171:1285–1300 DOI 10.1007/s00431-011-1553-z REVIEW Educational paper Ciliopathies Carsten Bergmann Received: 11 June 2011 /Accepted: 3 August 2011 /Published online: 7 September 2011 # The Author(s) 2011. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Cilia are antenna-like organelles found on the (NPHP) . Ivemark syndrome . Meckel syndrome (MKS) . surface of most cells. They transduce molecular signals Joubert syndrome (JBTS) . Bardet–Biedl syndrome (BBS) . and facilitate interactions between cells and their Alstrom syndrome . Short-rib polydactyly syndromes . environment. Ciliary dysfunction has been shown to Jeune syndrome (ATD) . Ellis-van Crefeld syndrome (EVC) . underlie a broad range of overlapping, clinically and Sensenbrenner syndrome . Primary ciliary dyskinesia genetically heterogeneous phenotypes, collectively (Kartagener syndrome) . von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) . termed ciliopathies. Literally, all organs can be affected. Tuberous sclerosis (TSC) . Oligogenic inheritance . Modifier. Frequent cilia-related manifestations are (poly)cystic Mutational load kidney disease, retinal degeneration, situs inversus, cardiac defects, polydactyly, other skeletal abnormalities, and defects of the central and peripheral nervous Introduction system, occurring either isolated or as part of syn- dromes. Characterization of ciliopathies and the decisive Defective cellular organelles such as mitochondria, perox- role of primary cilia in signal transduction and cell isomes, and lysosomes are well-known -

2 Surgical Anatomy

2 Surgical Anatomy Nancy Dugal Perrier, Michael Sean Boger contents 2.2 Morphology 2.1 Introduction . 7 The paired retroperitoneal adrenal glands are found 2.2 Morphology ...7 in the middle of the abdominal cavity, residing on 2.3 Relationship of the Adrenal Glands to the Kidneys ...10 the superior medial aspect of the upper pole of each 2.4 Blood Supply, Innervation, and Lymphatics ...10 kidney (Fig. 1). However, this location may vary 2.4.1 Arterial . 10 depending on the depth of adipose tissue.By means of 2.4.2 Venous ...10 pararenal fat and perirenal fascia,the adrenals contact 2.4.3 Innervation ...11 the superior portion of the abdominal wall. These 2.4.4 Lymphatic . 11 structures separate the adrenals from the pleural re- 2.5 Left Adrenal Gland Relationships ...11 flection, ribs, and the subcostal, sacrospinalis, and 2.6 Right Adrenal Gland Relationships ...14 latissimus dorsi muscles [2].Posteriorly,the glands lie 2.7 Summary ...17 References . 17 near the diaphragmatic crus and arcuate ligament [10]. Laterally, the right adrenal resides in front of the 12th rib and the left gland is in front of the 11th and 12th ribs [2]. Each adrenal gland weighs approximately 2.1 Introduction Liver Adrenal gland The small paired adrenal glands have a grand history. Eustachius published the first anatomical drawings of the adrenal glands in the mid-sixteenth century [17].In 1586, Piccolomineus and Baunin named them the suprarenal glands. Nearly two-and-a-half centuries later, Cuvier described the anatomical division of each gland into the cortex and medulla. -

Anatomical Variations in the Arterial Supply of the Suprarenal Gland. Int J Health Sci Res

International Journal of Health Sciences and Research www.ijhsr.org ISSN: 2249-9571 Original Research Article Anatomical Variations in the Arterial Supply of the Suprarenal Gland Sushma R.K1, Mahesh Dhoot2, Hemant Ashish Harode2, Antony Sylvan D’Souza3, Mamatha H4 1Lecturer, 2Postgraduate, 3Professor & Head, 4Assistant Professor; Department of Anatomy, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal University, Manipal-576104, Karnataka, India. Corresponding Author: Mamatha H Received: 29/03//2014 Revised: 17/04/2014 Accepted: 21/04/2014 ABSTRACT Introduction: Suprarenal gland is normally supplied by superior, middle and inferior suprarenal arteries which are the branches of inferior phrenic, abdominal aorta and renal artery respectively. However the arterial supply of the suprarenal gland may show variations. Therefore a study was conducted to find the variations in the arterial supply of Suprarenal Gland. Materials and methods: 20 Formalin fixed cadavers, were dissected bilaterally in the department of Anatomy, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal to study the arterial supply of the suprarenal gland, which were photographed and different variations were noted. Results: Out of 20 cadavers variations were observed in five cases in the arterial pattern of supra renal gland. We found that in one cadaver superior supra renal artery on the left side was arising directly from the coeliac trunk. Another variation was observed on the right side ina cadaver that inferior and middle suprarenal arteries were arising from accessory renal artery and on the right side it gave another small branch to the gland. Conclusion: Variations in the arterial pattern of suprarenal gland are significant for radiological and surgical interventions. KEY WORDS: Suprarenal gland, suprarenal artery, renal artery, abdominal aorta, inferior phrenic artery INTRODUCTION accessory renal arteries (ARA). -

Potter Syndrome: a Case Study

Case Report Clinical Case Reports International Published: 22 Sep, 2017 Potter Syndrome: A Case Study Konstantinidou P1,2, Chatzifotiou E1,2, Nikolaou A1,2, Moumou G1,2, Karakasi MV2, Pavlidis P2 and Anestakis D1* 1Laboratory of Forensic and Toxicology, Department of Histopathology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece 2Laboratory of Forensic Sciences, Department of Histopathology, Democritus University of Thrace School, Greece Abstract Potter syndrome (PS) is a term used to describe a typical physical appearance, which is the result of dramatically decreased amniotic fluid volume secondary to renal diseases such as bilateral renal agenesis (BRA). Other causes are abstraction of the urinary tract, autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD), autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) and renal hypoplasia. In 1946, Edith Potter characterized this prenatal renal failure/renal agenesis and the resulting physical characteristics of the fetus/infant that result from oligohydramnios as well as the complete absence of amniotic fluid (anhydramnios). Oligohydramnios and anhydramnios can also be due to the result of leakage of amniotic fluid from rupturing of the amniotic membranes. The case reported concerns of stillborn boy with Potter syndrome. Keywords: Potter syndrome; Polycystic kidney disease; Oligohydramnios sequence Introduction Potter syndrome is not technically a ‘syndrome’ as it does not collectively present with the same telltale characteristics and symptoms in every case. It is technically a ‘sequence’, or chain of events - that may have different beginnings, but ends with the same conclusion. Below are the different ways that Potter syndrome (A.K.A Potter sequence) can begin due to various causes of renal failure. They gave numbers to differentiate the different forms, but this system had not caught in the medical and scientific communities [1]. -

Adrenal Metastasis from an Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma - a Case Report and Review of Literature

IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences (IOSR-JDMS) e-ISSN: 2279-0853, p-ISSN: 2279-0861.Volume 15, Issue 10 Ver. VII (October. 2016), PP 20-22 www.iosrjournals.org Adrenal Metastasis from an Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma - A Case Report and Review of Literature Prof. Subbiah Shanmugam MS Mch1, Dr Sujay Susikar MS Mch2, Dr. H Prasanna Srinivasa Rao Mch Post Graduate2 1,2Department Of Surgical Oncology, Centre For Oncology, Government Royapettah Hospital & Kilpauk Medical College, Chennai, India Abstract: Adrenal metastasis from esophageal carcinoma is quite uncommon. The identification of adrenal metastasis and their differentiation from incidentally detected benign adrenal tumors is challenging especially when functional imaging facilities are unavailable. Here we present a case report of a 43 year old male presenting with adrenal metastasis from an esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. The use of minimally invasive surgery to confirm the metastatic nature of disease in a resource limited setup has been described. Keywords: adrenal metastasis, adrenalectomy, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma I. Introduction Adrenal metastases have been reported in various malignancies; most commonly from cancers of lung, breast but uncommonly from esophageal primary. The diagnostic difficulties in the identification of adrenal secondaries are due to the small size of the lesion, difficulty in differentiating benign from malignant adrenal lesions based on computed tomography findings alone and the anatomical position of adrenal making it difficult to target for biopsy under image guidance. The functional scans (PET CT) not only reliably differentiate metastatic adrenal lesions, but also light up other areas of metastasis. Such information is definitely needed before deciding on the intent of treatment and the surgery for the primary lesion. -

A Study on the Variations of Arterial Supply to Adrenal Gland

K Naga Vidya Lakshmi and Mahesh Dhoot / International Journal of Biomedical and Advance Research 2016; 7(8): 373-375. 373 International Journal of Biomedical and Advance Research ISSN: 2229-3809 (Online); 2455-0558 (Print) Journal DOI: 10.7439/ijbar CODEN: IJBABN Original Research Article A study on the variations of arterial supply to adrenal gland K Naga Vidya Lakshmi* and Mahesh Dhoot Department of Anatomy, RKDF Medical College Hospital & Research Centre, Bhopal, India *Correspondence Info: Dr. K Naga Vidya Lakshmi, Room No: 208, Staff Quarters, RKDF Medical College Campus, Jatkhedi, Bhopal, India E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Introduction: Adrenal glands are richly vascular and get their arterial supply by means of three arteries namely superior, middle, inferior suprarenal arteries. The inferior phrenic artery gives off the superior branch, while middle branch arises directly from the abdominal aorta, and the inferior suprarenal branch is given off by the renal artery. Materials And Methods: The study was conducted in 15 formalin fixed cadavers obtained from the department of Anatomy and are carefully dissected to observe the arterial supply of both right and left adrenal glands. Observations: It has been noted that variations were observed in four cases out of 30 adrenal glands, two cases showed variations on right side and in two cases variation is seen on left side. First case on the right side, both MSA and ISA are given off by ARA. In the second case on right side IPA is given off by RA and from the junction of these two arteries MSA was given. In third case on left side MSA is given by the coeliac trunk and ISA is from ARA, in fourth case on left side ISA is originated from ARA. -

A Case of Bilateral Aldosterone-Producing Adenomas Differentiated by Segmental Adrenal Venous Sampling for Bilateral Adrenal Sparing Surgery

OPEN Journal of Human Hypertension (2016) 30, 379–385 © 2016 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0950-9240/16 www.nature.com/jhh ORIGINAL ARTICLE A case of bilateral aldosterone-producing adenomas differentiated by segmental adrenal venous sampling for bilateral adrenal sparing surgery R Morimoto1, N Satani2, Y Iwakura1, Y Ono1, M Kudo1, M Nezu1, K Omata1,3, Y Tezuka1,3, K Seiji2,HOta2, Y Kawasaki4, S Ishidoya4, Y Nakamura5, Y Arai4, K Takase2, H Sasano5,SIto1 and F Satoh1,3 Primary aldosteronism due to unilateral aldosterone-producing adenoma (APA) is a surgically curable form of hypertension. Bilateral APA can also be surgically curable in theory but few successful cases can be found in the literature. It has been reported that even using successful adrenal venous sampling (AVS) via bilateral adrenal central veins, it is extremely difficult to differentiate bilateral APA from bilateral idiopathic hyperaldosteronism (IHA) harbouring computed tomography (CT)-detectable bilateral adrenocortical nodules. We report a case of bilateral APA diagnosed by segmental AVS (S-AVS) and blood sampling via intra-adrenal first-degree tributary veins to localize the sites of intra-adrenal hormone production. A 36-year-old man with marked long-standing hypertension was referred to us with a clinical diagnosis of bilateral APA. He had typical clinical and laboratory profiles of marked hypertension, hypokalaemia, elevated plasma aldosterone concentration (PAC) of 45.1 ng dl− 1 and aldosterone renin activity ratio of 90.2 (ng dl − 1 per ng ml − 1 h − 1), which was still high after 50 mg-captopril loading. CT revealed bilateral adrenocortical tumours of 10 and 12 mm in diameter on the right and left sides, respectively. -

Potter Syndrome, a Rare Entity with High Recurrence Risk in Women with Renal Malformations – Case Report and a Review of the Literature

CASE PRESENTATIONS Ref: Ro J Pediatr. 2017;66(2) DOI: 10.37897/RJP.2017.2.9 POTTER SYNDROME, A RARE ENTITY WITH HIGH RECURRENCE RISK IN WOMEN WITH RENAL MALFORMATIONS – CASE REPORT AND A REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE George Rolea1, Claudiu Marginean1, Vladut Stefan Sasaran2, Cristian Dan Marginean2, Lorena Elena Melit3 1Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinic 1, Tirgu Mures 2University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Tirgu Mures 3Pediatrics Clinic 1, Tirgu Mures ABSTRACT Potter syndrome represents an association between a specific phenotype and pulmonary hypoplasia as a result of oligohydramnios that can appear in different pathological conditions. Thus, Potter syndrome type 1 or auto- somal recessive polycystic renal disease is a relatively rare pathology and with poor prognosis when it is diag- nosed during the intrauterine life. We present the case of a 24-year-old female with an evolving pregnancy, 22/23 gestational weeks, in which the fetal ultrasound revealed oligohydramnios, polycystic renal dysplasia and pulmonary hypoplasia. The personal pathological history revealed the fact that 2 years before this pregnancy, the patient presented a therapeutic abortion at 16 gestational weeks for the same reasons. The maternal ultra- sound showed unilateral maternal renal agenesis. Due to the fact that the identified fetal malformation was in- compatible with life, we decided to induce the therapeutic abortion. The particularity of the case consists in di- agnosing Potter syndrome in two successive pregnancies in a 24-year-old female, without any significant -

Glossary of Pediatric Endocrine Terms

Glossary of Pediatric Endocrine Terms Adrenal Glands: Triangle-shaped glands located on top of each kidney that are responsible for the regulation of stress response by producing hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline. Adrenal Crisis: A life-threatening condition that results when there is not enough cortisol (stress hormone) in the body. This may present with nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, severely low blood pressure, and loss of consciousness. Adrenocorticotropin (ACTH): A hormone produced by the anterior pituitary gland that triggers the adrenal gland to produce cortisol, the stress hormone. Anterior Pituitary: The front of the pituitary gland that secretes growth hormone, gonadotropins, thyroid stimulating hormone, prolactin, adrenocorticotropin hormone. Antidiuretic Hormone: A hormone secreted by the posterior pituitary that controls how much water is excreted by the kidneys (water balance). Bone Age Study: An X-ray of the left hand and wrist to assess a child’s skeletal age. It is often used to evaluate disorders of puberty and growth. Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia: A group of disorders which impair the adrenal steroid synthesis pathway. This causes the body makes too many androgens. Sometimes the body does not make enough cortisol and aldosterone. Constitutional Delay of Growth and Puberty: A normal variant of growth in which children grow at a slower rate and begin puberty later than their peers. They may appear short until they have catch up growth. They usually end up at a normal adult height. A diagnosis of constitutional delay of growth and puberty is often referred to as being a “late bloomer.” Cortisol: The “stress hormone”, which is produced by the adrenal glands. -

Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitors

J Med Genet 1997;34:541-545 541 Congenital renal tubular dysplasia and skull ossification defects similar to teratogenic effects of J Med Genet: first published as 10.1136/jmg.34.7.541 on 1 July 1997. Downloaded from angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors Dhavendra Kumar, Gail Moss, Rob Primhak, Robert Coombs Abstract An apparently autosomal recessive syn- drome of congenital renal tubular dyspla- sia and skull ossification defects is described in five infants from two sepa- rate, consanguineous, Pakistani Muslim kindreds. The clinical, pathological, and Centre for Human Genetics, 117 radiological features are similar to the Manchester Road, phenotype associated with fetal exposure Sheffield S1O 5DN, UK to angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) D Kumar inhibitors: intrauterine growth retarda- Department of tion, skull ossification defects, and fetal/ Paediatrics, Sheffield neonatal anuric renal failure associated Children's Hospital, with renal tubular dysplasia. There was no Sheffield, UK fetal exposure to ACE inhibitors in the G Moss affected infants. similarities R Primhak Phenotypic between these familial cases and those Neonatal Unit, Jessop associated with ACE inhibition suggest an Hospital for Women, abnormality of the "renin-angiotensin- Sheffield, UK aldosterone" system (RAS). It is postu- R Coombs lated that the molecular pathology in this Correspondence to: uncommon autosomal recessive proximal Dr Kumar. renal tubular dysgenesis could be related http://jmg.bmj.com/ to mutations of the Received 4 March 1996 gene systems govern- Revised version accepted for ing the RAS. publication 6 March 1997 (JMed Genet 1997;34:541-545) Figure 2 Skull radiograph ofIV.5,family 1: note poor ossification and wide skull sutures. -

The Human Digestive System

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 070 912 AC 014 054 TITLE Plants and Photosynthesis: Level III, Unit 3, Lesson 1; The Human Digestive System: Lesson 2; Functions of the Blood: Lesson 3; Human Circulation and .respiration: Lesson 4; Reproduction of a Single Cell: Lesson 5; Reproduction by Male and Female cells: Lesson 6; The Human Reproductive System: Lesson 7; Genetics and Heredity: Lesson 8; The Nervous System: Lesson 9; The Glandular System: Lesson 10. Advanced General Education Program. A High School Self-Study Program. INSTITUTION Manpower Administration (DOL), Washington, D. C. Job Corps. REPORT NO PM-431-84; PM-431-85; PM-431-86; PM-431-87; PM-431-88; PM-431-89; PM-431-90; PM-431-91; PM-431-92; PM-431-93 PUB DATE Nov 69 .NOTE 365p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$13.16 DESCRIPTORS *Academic Education; Achievement Tests; *Autoinstructional Aids; Biology; *Course Content; Credit Courses; *General Education; Human Body; *Independent Study; Photosynthesis; Plant Growth; Secondary Grades ABSTRACT This self-study program for the high-school level contains lessons in the following subjects: Plants and Photosynthesis; The Human Digestive System; Functions of the Blood; Human Circulation and Respiration; Reproduction ofa Single Cell; Reproduction by Male and Female Cells; The Human Reproductive System; Genetics and Heredity; The Nervous System; and The Glandular System. Each lesson concludes with a Mastery Test to be completed by the student. (DB) PM 431 - 84 U S DEPARTMENT OFHEALTH EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HASBEEN REPRO DUCED EXACTLY ASRECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG INATING IT POINTS OFVIEW OR OPIN IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICEOF EDU CATION POSITION ORPOLICY ADVANCED GENERALEDUCATIONPROGRAM A HIGH SCHOOL SELF-STUDY PROGRAM PLANTS ANDPHOTOSYNTHESIS LEVEL: III UNIT: 3 LESSON: 1 IoNT0, 11S rt V 1.4 N-L 1/4rty 14 U.S. -

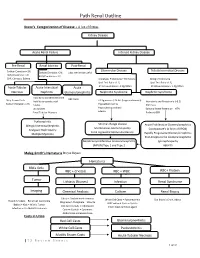

Path Renal Outline

Path Renal Outline Krane’s Categorization of Disease + A lot of Extras Kidney Disease Acute Renal Failure Intrinsic Kidney Disease Pre‐Renal Renal Intrinsic Post‐Renal Sodium Excretion <1% Glomerular Disease Tubulointerstitial Disease Sodium Excretion < 1% Sodium Excretion >2% Labs aren’t that useful BUN/Creatinine > 20 BUN/Creatinine < 10 CHF, Cirrhosis, Edema Urinalysis: Proteinuria + Hematuria Benign Proteinuria Spot Test Ratio >1.5, Spot Test Ratio <1.5, Acute Tubular Acute Interstitial Acute 24 Urine contains > 2.0g/24hrs 24 Urine contains < 1.0g/24hrs Necrosis Nephritis Glomerulonephritis Nephrotic Syndrome Nephritic Syndrome Inability to concentrate Urine RBC Casts Dirty Brown Casts Inability to secrete acid >3.5g protein / 24 hrs (huge proteinuria) Hematuria and Proteinuria (<3.5) Sodium Excretion >2% Edema Hypoalbuminemia RBC Casts Hypercholesterolemia Leukocytes Salt and Water Retention = HTN Focal Tubular Necrosis Edema Reduced GFR Pyelonephritis Minimal change disease Allergic Interstitial Nephritis Acute Proliferative Glomerulonephritis Membranous Glomerulopathy Analgesic Nephropathy Goodpasture’s (a form of RPGN) Focal segmental Glomerulosclerosis Rapidly Progressive Glomerulonephritis Multiple Myeloma Post‐Streptococcal Glomerulonephritis Membranoproliferative Glomerulonephritis IgA nephropathy (MPGN) Type 1 and Type 2 Alport’s Meleg‐Smith’s Hematuria Break Down Hematuria RBCs Only RBC + Crystals RBC + WBC RBC+ Protein Tumor Lithiasis (Stones) Infection Renal Syndrome Imaging Chemical Analysis Culture Renal Biopsy Calcium