Historical Summary of Cryogenic Activity Prior to 1950 (2007)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9 Xenon Handling and Cryogenics

9 Xenon Handling and Cryogenics 9.1 Overview The Xe handling and cryogenics strategy of LZ derives strongly from the successful LUX program and takes maximum advantage of key technologies demonstrated there: chromatographic krypton removal, high-flow online purification, high-efficiency two-phase heat exchange, sensitive in situ monitoring of Xe purity, and thermosyphon cryogenics. In many cases, the primary technical challenge of the LZ implementation is how to best scale up from LUX. Two classes of impurities are of concern: electronegatives such as O2 and H2O that suppress charge and light transport in the TPC, and radioactive noble gases such as 85Kr, 39Ar, and 222Rn that create backgrounds that are not amenable to self-shielding. Both types of impurities may be found in the vendor- supplied Xe, and both may also be introduced into the detector during operations via outgassing and emanation. The purity goals are summarized in Table 9.1.1. We have three mitigation techniques to control these impurities. First, electronegatives are suppressed during operations by continuous circulation of the Xe in gaseous form through a hot (450 oC) zirconium getter. Gettering in the gas phase is made practical by a two-phase heat exchanger. A metal-diaphragm gas pump drives the circulation and the system is capable of purifying the entire Xe stockpile in 2.3 days. Second, the problematic radioactive species, 85Kr and 39Ar, which have relatively long half-lives (10.8 years and 269 years, respectively) and no supporting parents, can be removed from the vendor-supplied Xe prior to the start of operations. -

Cryogenics in Space

— 37 — Cryogenics in space Nicola RandoI Abstract Cryogenics plays a key role on board space-science missions, with a range of applications, mainly in the domain of astrophysics. Indeed a tremendous progress has been achieved over the last 20 years in cryogenics, with enhanced reliability and simpler operations, thus matching the needs of advanced focal-plane detectors and complex science instrumentation. In this article we provide an overview of recent applications of cryogenics in space, with specific emphasis on science missions. The overview includes an analysis of the impact of cryogenics on the spacecraft system design and of the main technical solutions presently adopted. Critical technology developments and programmatic aspects are also addressed, including specific needs of future science missions and lessons learnt from recent programmes. Introduction H. Kamerlingh-Onnes liquefied 4He for the first time in 1908 and discovered superconductivity in 1911. About 100 years after such achievements (Pobell 1996), cryogenics plays a key role on board space-science missions, providing the environ- ment required to perform highly sensitive measurements by suppressing the thermal background radiation and allowing advantage to be taken of the performance of cryogenic detectors. In the last 20 years several spacecraft have been equipped with cryogenic in- strumentation. Among such missions we should mention IRAS (launched in 1983), ESA’s ISO (launched in 1995) (Kessler et al 1996) and, more recently, NASA’s Spitzer (formerly SIRTF, launched in 2006) (Werner 2005) and the Japanese mis- sion Akari (IR astronomy mission launched in 2006) (Shibai 2007). New missions involving cryogenics are the ESA missions Planck (dedicated to the mapping of the cosmic background radiation) and Herschel (far infrared and sub-millimetre observatory), carrying instruments operating at temperatures of 0.1 K and 0.3 K, respectively (Crone et al 2006). -

Producing Nitrogen Via Pressure Swing Adsorption

Reactions and Separations Producing Nitrogen via Pressure Swing Adsorption Svetlana Ivanova Pressure swing adsorption (PSA) can be a Robert Lewis Air Products cost-effective method of onsite nitrogen generation for a wide range of purity and flow requirements. itrogen gas is a staple of the chemical industry. effective, and convenient for chemical processors. Multiple Because it is an inert gas, nitrogen is suitable for a nitrogen technologies and supply modes now exist to meet a Nwide range of applications covering various aspects range of specifications, including purity, usage pattern, por- of chemical manufacturing, processing, handling, and tability, footprint, and power consumption. Choosing among shipping. Due to its low reactivity, nitrogen is an excellent supply options can be a challenge. Onsite nitrogen genera- blanketing and purging gas that can be used to protect valu- tors, such as pressure swing adsorption (PSA) or membrane able products from harmful contaminants. It also enables the systems, can be more cost-effective than traditional cryo- safe storage and use of flammable compounds, and can help genic distillation or stored liquid nitrogen, particularly if an prevent combustible dust explosions. Nitrogen gas can be extremely high purity (e.g., 99.9999%) is not required. used to remove contaminants from process streams through methods such as stripping and sparging. Generating nitrogen gas Because of the widespread and growing use of nitrogen Industrial nitrogen gas can be produced by either in the chemical process industries (CPI), industrial gas com- cryogenic fractional distillation of liquefied air, or separa- panies have been continually improving methods of nitrogen tion of gaseous air using adsorption or permeation. -

Cryogenics – the Basics Or Pre-Basics Lesson 1 D

Cryogenics – The Basics or Pre-Basics Lesson 1 D. Kashy Version 3 Lesson 1 - Objectives • Look at common liquids and gases to get a feeling for their properties • Look at Nitrogen and Helium • Discuss Pressure and Temperature Scales • Learn more about different phases of these fluids • Become familiar with some cryogenic fluids properties Liquids – Water (a good reference) H2O density is 1 g/cc 10cm Total weight 1000g or 1kg (2.2lbs) Cube of water – volume 1000cc = 1 liter Liquids – Motor Oil 10cm 15W30 density is 0.9 g/cc Total weight 900g or 0.9 kg (2lbs) Cube of motor oil – volume 1000cc = 1 liter Density can and usually does change with temperature 15W30 Oil Properties Density Curve Density scale Viscosity scale Viscosity Curve Water density vs temperature What happens here? What happens here? Note: This plot is for SATURATED Water – Discussed soon Water and Ice Water Phase Diagram Temperature and Pressure scales • Fahrenheit: 32F water freezes 212 water boils (at atmospheric pressure) • Celsius: 0C water freezes and 100C water boils (again at atmospheric pressure) • Kelvin: 273.15 water freezes and 373.15 water boils (0K is absolute zero – All motion would stop even electrons around a nucleus) • psi (pounds per square in) one can reference absolute pressure or “gage” pressure (psia or psig) • 14.7psia is one Atmosphere • 0 Atmosphere is absolute vacuum, and 0psia and -14.7psig • Standard Temperature and Pressure (STP) is 20C (68F) and 1 atm Temperature Scales Gases– Air Air density is 1.2kg/m3 => NO Kidding! 100cm =1m Total weight -

Cryogenicscryogenics Forfor Particleparticle Acceleratorsaccelerators Ph

CryogenicsCryogenics forfor particleparticle acceleratorsaccelerators Ph. Lebrun CAS Course in General Accelerator Physics Divonne-les-Bains, 23-27 February 2009 Contents • Low temperatures and liquefied gases • Cryogenics in accelerators • Properties of fluids • Heat transfer & thermal insulation • Cryogenic distribution & cooling schemes • Refrigeration & liquefaction Contents • Low temperatures and liquefied gases ••• CryogenicsCryogenicsCryogenics ininin acceleratorsacceleratorsaccelerators ••• PropertiesPropertiesProperties ofofof fluidsfluidsfluids ••• HeatHeatHeat transfertransfertransfer &&& thermalthermalthermal insulationinsulationinsulation ••• CryogenicCryogenicCryogenic distributiondistributiondistribution &&& coolingcoolingcooling schemesschemesschemes ••• RefrigerationRefrigerationRefrigeration &&& liquefactionliquefactionliquefaction • cryogenics, that branch of physics which deals with the production of very low temperatures and their effects on matter Oxford English Dictionary 2nd edition, Oxford University Press (1989) • cryogenics, the science and technology of temperatures below 120 K New International Dictionary of Refrigeration 3rd edition, IIF-IIR Paris (1975) Characteristic temperatures of cryogens Triple point Normal boiling Critical Cryogen [K] point [K] point [K] Methane 90.7 111.6 190.5 Oxygen 54.4 90.2 154.6 Argon 83.8 87.3 150.9 Nitrogen 63.1 77.3 126.2 Neon 24.6 27.1 44.4 Hydrogen 13.8 20.4 33.2 Helium 2.2 (*) 4.2 5.2 (*): λ Point Densification, liquefaction & separation of gases LNG Rocket fuels LIN & LOX 130 000 m3 LNG carrier with double hull Ariane 5 25 t LHY, 130 t LOX Air separation by cryogenic distillation Up to 4500 t/day LOX What is a low temperature? • The entropy of a thermodynamical system in a macrostate corresponding to a multiplicity W of microstates is S = kB ln W • Adding reversibly heat dQ to the system results in a change of its entropy dS with a proportionality factor T T = dQ/dS ⇒ high temperature: heating produces small entropy change ⇒ low temperature: heating produces large entropy change L. -

“Is Cryonics an Ethical Means of Life Extension?” Rebekah Cron University of Exeter 2014

1 “Is Cryonics an Ethical Means of Life Extension?” Rebekah Cron University of Exeter 2014 2 “We all know we must die. But that, say the immortalists, is no longer true… Science has progressed so far that we are morally bound to seek solutions, just as we would be morally bound to prevent a real tsunami if we knew how” - Bryan Appleyard 1 “The moral argument for cryonics is that it's wrong to discontinue care of an unconscious person when they can still be rescued. This is why people who fall unconscious are taken to hospital by ambulance, why they will be maintained for weeks in intensive care if necessary, and why they will still be cared for even if they don't fully awaken after that. It is a moral imperative to care for unconscious people as long as there remains reasonable hope for recovery.” - ALCOR 2 “How many cryonicists does it take to screw in a light bulb? …None – they just sit in the dark and wait for the technology to improve” 3 - Sterling Blake 1 Appleyard 2008. Page 22-23 2 Alcor.org: ‘Frequently Asked Questions’ 2014 3 Blake 1996. Page 72 3 Introduction Biologists have known for some time that certain organisms can survive for sustained time periods in what is essentially a death"like state. The North American Wood Frog, for example, shuts down its entire body system in winter; its heart stops beating and its whole body is frozen, until summer returns; at which point it thaws and ‘comes back to life’ 4. -

The Liquefaction of Helium., In: KNAW, Proceedings, 11, 1908-1909, Amsterdam, 1909, Pp

Huygens Institute - Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW) Citation: H. Kamerlingh Onnes, The liquefaction of helium., in: KNAW, Proceedings, 11, 1908-1909, Amsterdam, 1909, pp. 168-185 This PDF was made on 24 September 2010, from the 'Digital Library' of the Dutch History of Science Web Center (www.dwc.knaw.nl) > 'Digital Library > Proceedings of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW), http://www.digitallibrary.nl' - 1 - ( 16B ) The Ieftha,nd part agrees then perfectly with BAKHUIS ROOZEBOOl\I)S spacial figul'e, 0 A and OB not representing the melting-points under vapour-pressure, but the tra,nsition points of the two components under vapoul' pressure, i. e. the points where the ordinary cl'ystalline state passes to the tIuid cl'ystalline state under t11e pressure of its vapour. If this spacial figm'e is cut by a plane of constant pressnre, we get, at least if this pressure is chosen high en'ough, the simplest imaginabie T-X-fignre of a system of two components, each of which possesses a stabie fluid-crystalline modification. The other possible cases may be easily derived from this spaeial figure. Amste1,dam June 1908. Anol'g. LYtem. Laboratorium of the University. Physics. - "Tlte liquefaction of helium". By Prof. H. KAIIIERLINGH ONNES. Oommunication N°. 108 from the Physical Laboratory at Leiden. 9 1. Met/wd. As a fil'st step on the road towards the liquefaction of helium the theory of VAN DER ·WAALS indicated the determination of its isotherms, particularly for the tempel'atures which are to be attained by means of l~quid hydl'ogen. -

Louis Paul Cailletet-The Liquefaction of the Permanent Gases

Educator Indian Journal of Chemi cal Techn ology Vol. I 0. March 20m. pp. 22:l-23(i Louis Paul Cailletet-The liquefaction of the permanent gases 1 Jaime Wi sniak ' ' Department of Chemical Engi neering. 13cn-G urion Universi ty or the cgcv. Bccr-S hcva. Israel R4 10.') To Louis Paul Ca illetct ( l lD 1- 1913) we owe th e rea lization of th e liquefaction of perma nent gases using a free expa n sion process. A brillian t analysis of an ex perimental mishap led him to ac hieve thi s possib ility. The priority or oxygen lique faction was and continues to be a matter of disc uss ion. The life and sc ientific work or Caillctet arc descri bed toget her w ith detai ls about the priority polem ic. 4 Mankind has been interes ted in quantifying th e differ through the wai Is of th e vesse l . However, if th e I iq ence bet ween hot and cold si nee very old times. The uid evaporated into a vacuum surrounded by a freez ori gi nal apparatus, ca lled th ennoscopes, served ing mi xture th e cooling effec t could be increased in merely to show the changes in th e ten~perature of its definitely as long as the liquid exerted an appreciable surroundings. Eventually th e need arose for qu anti vapour pressure. John Leslie ( 1766-1 832) not on ly fying these observations and th e eli fferent th ermome had been able to freeze water by absorbing its vapour ters began to be developed. -

Cryogenic Transport Trailers

CRYOGENIC TRANSPORT TRAILERS Worthington Industries delivers end-to-end solutions for storing and transporting cryogenic liquids. Our high- quality custom trailers are manufactured at our production facility in Theodore, Alabama. Worthington's transport trailers are customized to meet your unique needs and designed to operate for years to come, which means dependable fleets with lower transportation, maintenance and refurbishment costs. We’re always seeking new ways to increase your productivity, performance and value. Our trailers feature lightweight aluminum or stainless steel liners for the safe transportation of the specialty liquefied gases such as: • Liquid Nitrogen (LIN) • Liquid Argon (LAR) • Liquid Oxygen (LOX) • Liquid Hydrogen (LH2) • Liquid Natural Gas (LNG) OUR ENGINEERS WILL WORK WITH YOU TO DETERMINE THE BEST CONFIGURATION FOR YOUR OPERATION. LIN LAR LOX LH2 LNG Spec ATL8400-33PE ATL5150-40PH 6000STL-40PE 17900STL-165P ATL12800-70P (Engine drive) (Hydraulic drive) (Engine drive) ATL8400-33PH (Engine drive 6000STL-40PH (Hydraulic drive) available) (Hydraulic drive) ATL8400-33PL (Electrical drive) Gross Capacity (gallons) 8,400 5,150 6,000 17,900 12,800 Pressure (PSI) 33 40 40 165 70 Inner Vessel Material Alum Alum SS SS Alum Outer Vessel Material Alum Alum C or C/SS C or C/SS C or C/SS *Alum = Aluminum, SS = Stainless Steel, C = Carbon Steel ASME CERTIFIED, ASME U STAMP, NATIONAL BOARD CERTIFIED, DOT-APPROVED (#CT-13707), REPAIR OR BUILD TO MC -331, MC-338 anD CGA-341 4075 HAMILTON ROAD THEODORE, ALABAMA 36582 P: 844.273.7517 [email protected] WORTHINGTONINDUSTRIES.COM/TRANSPORTTRAILERS © 2018, Worthington Industries Inc. 07/18 CRYOGENIC TRANSPORT TRAILER REPAIRS Worthington Industries offers full rehab as well as DOT inspection and certification of cryogenic trailers in our Theodore, Alabama facility. -

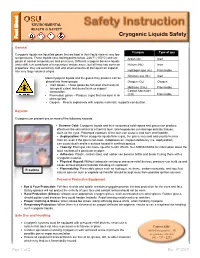

Cryogenic Liquids

ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH & SAFETY Cryogenic Liquids Safety Fact Sheet Fact General Cryogen Type of gas Cryogenic liquids are liquefied gases that are kept in their liquid state at very low temperatures. These liquids have boiling points below -238°F (-150°C) and are Argon (Ar) Inert gases at normal temperatures and pressures. Different cryogens become liquids under different conditions of temperature and pressure, but all have two common Helium (He) Inert properties: they are extremely cold and small amounts of the liquid can expand into very large volumes of gas. Hydrogen gas (H2) Flammable Nitrogen gas (N2) Inert Most cryogenic liquids and the gases they produce can be placed into three groups: Oxygen (O2) Oxygen Inert gases – These gases do not react chemically to any great extent and do not burn or support Methane (CH4) Flammable combustion. Carbon Monoxide Flammable gases – Produce a gas that can burn in air (CO) Flammable when ignited. Oxygen – Reacts explosively with organic materials; supports combustion. Hazards Cryogens can present one or more of the following hazards: Extreme Cold: Cryogenic liquids and their associated cold vapors and gases can produce effects on the skin similar to a thermal burn. Brief exposures can damage delicate tissues, such as the eyes. Prolonged exposure of the skin can cause a cold burn and frostbite. Asphyxiation: When cryogenic liquids form a gas, the gas is very cold and usually heavier than air; even if the gas is non-toxic, it displaces air. Oxygen deficiency (i.e. asphyxiation) can cause death and is a serious hazard in confined spaces. Toxicity: Each gas can cause specific health effects. -

Properties of Cryogenic Insulants J

Cryogenics 38 (1998) 1063–1081 1998 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved Printed in Great Britain PII: S0011-2275(98)00094-0 0011-2275/98/$ - see front matter Properties of cryogenic insulants J. Gerhold Technische Universitat Graz, Institut fur Electrische Maschinen und Antriebestechnik, Kopernikusgasse 24, A-8010 Graz, Austria Received 27 April 1998; revised 18 June 1998 High vacuum, cold gases and liquids, and solids are the principal insulating materials for superconducting apparatus. All these insulants have been claimed to show fairly good intrinsic dielectric performance under laboratory conditions where small scale experiments in the short term range are typical. However, the insulants must be inte- grated into large scaled insulating systems which must withstand any particular stress- ing voltage seen by the actual apparatus over the full life period. Estimation of the amount of degradation needs a reliable extrapolation from small scale experimental data. The latter are reviewed in the light of new experimental data, and guidelines for extrapolation are discussed. No degradation may be seen in resistivity and permit- tivity. Dielectric losses in liquids, however, show some degradation, and breakdown as a statistical event must be scrutinized very critically. Although information for break- down strength degradation in large systems is still fragmentary, some thumb rules can be recommended for design. 1998 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved Keywords: dielectric properties; vacuum; fluids; solids; power applications; supercon- ductors The dielectric insulation design of any superconducting Of special interest for normal operation are the resis- power apparatus must be based on the available insulators. tivity, the permittivity, and the dielectric losses. -

Developed and Maintained by the NFCC Contents

Developed and maintained by the NFCC Contents The gas laws ................................................................................................................................................. 3 The liquefaction of gases ..................................................................................................................... 3 Critical temperature and pressure .................................................................................................... 4 Liquefied gases in cylinders ................................................................................................................ 4 Sublimation ........................................................................................................................................... 5 This content is only valid at the time of download - 4-10-2021 00:25 2 of 5 The gas laws There are three gas laws: Boyle's Law – for a gas at constant temperature, the volume of a gas is inversely proportional to the pressure upon it. If V1 and P1 are the initial volume and pressure, and V2 and P2 are the final volumes and pressure, then V1 x P1 = V2 x P2 Charles' Law – the volume of a given mass of gas at constant pressure increases by 1/273 of its volume for every 1°C rise in temperature. The relationship between volume and temperature is: V1 / T1 = V2 / T2 where V1 and T1 are the initial volume and absolute temperature and V2 and T2 are the final volume and absolute temperature (the Kelvin temperature, not the Celsius temperature). In other words, the volume of