UNIVERSITY of CAPE TOWN Universityfebruary 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the February 2012 Issue

We are proud of the service we have provided to Trustees and Owners of Bodies Corporate and Homeowners Associations over 15 years. If we don’t already manage your apartment block or complex, we would like to. CONTACT Mike Morey TEL (021) 426 4440 FAX (021) 426 0777 EMAIL [email protected] VOLUME 29 No 1 FEBRUARY 2012 5772 www.cjc.org.za Hope and healing at BOD and Friends16082_Earspace of the for Jewish UJC Chronicle Cape FA.indd 1 Town —2011/08/19 10:40 AM Black Management Forum event securing foundations for the future By Dan Brotman Marco Van Embden, Hugh Herman and Eliot Osrin present a gift to Helen Zille. BMF member Mzo Tshaka, Cape Board Chairman Li Boiskin, Executive Director David The Friends of the UJC Cape Town recently Jacobson, Media & Diplomatic Liaison Dan Brotman, BMF member Songezo Mabece, BMF hosted a glittering and glamourous event — YP Chairman Thuso Segopolo, Ontlametse Phalatse and Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi. (Photo: Jason Boud) celebrating the South African Jewish A new Torah to community and the generosity that The Cape Board was recently approached in a collaborative effort between the sustains it. by the Black Management Forum (of which Black Management Forum, the Jewish celebrate 7 years it is a member) to assist with the visit community of Cape Town and several uests from around the world as well of a remarkable 12-year-old girl named large corporations creating an event to as leaders and donors from the Ontlametse Phalatse. honour Ontlametse. G community gathered to celebrate the In true South African spirit, the Nelson institutions and philanthropy that make this ntlametse, who lives with her mother Mandela Auditorium and Café Riteve were such a thriving community. -

Torah Mitzion

A compilation of Torat Eretz Yisrael by Torah MiTzion ממלכת כהנים וגוי קדוש Judaism, Zionism and Tikkun Olam בס״ד Opening Message from Zeev Schwartz Founding Executive Director Dear Friends, shlichim participate in an online, international Beit Midrash Since its inception 23 years ago, – Lilmod.org. Offering over Torah MiTzion has been a leading 400 shiurim a year in German, force of Religious Zionism in the Russian and French, the program Diaspora. Only last year our Batei brings together learners from 20 Midrash hosted 14,000 Chavruta countries! hours and 46,000 participants in various events and activities. The fulfillment of the verse from the prophet Isiah "for out of Zion The founding Rosh Yeshiva of the Torah MiTzion was shall the Torah come forth, and the Hesder Yeshiva in Ma'aleh Adumin, established with the goal word of the Lord from Jerusalem" Rabbi Haim Sabbato, defines the expresses perfectly the vision shlichim's mission as "Every day of strengthening Jewish of Torah Mitzion – a worldwide that we bring someone closer communities around the movement. to Torah, to Yir'at Shamayim, to Judaism – has no substitute. We globe and infusing them In the following pages we are will not be able to do tomorrow with the love for Torah, happy to share a taste of our what we did not accomplish today". shlichim's impact in communities the Jewish People and worldwide. Thousands of Jews from the State of Israel communities that do not Looking forward to seeing you in have the opportunity to host Israel! Torah MiTzion Staff, Israel Shabbat & Am Yisrael as Centers of Kedusha Rabbi Yedidya Noiman Rosh Kollel Montreal by numbers, from Shabbat and until ’...שָׁם שָׂם לוֹ חֹק ו ּ ּמִשְׁפָט וְשָׁם ּנִסָהו ּ’ Shabbat. -

Chassidus on the Eh're Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) RE ’EH _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah The Merit of Charity Compound forms of verbs usually indicate thoroughness. Yet when the Torah tells us (14:22), “You shall fully tithe ( aser te’aser ) all the produce of your field,” our Sages derive another concept. “ Aser bishvil shetis’asher ,” they say. “Tithe in order that you shall become wealthy.” Why is this so? When the charity a person gives, explains Rav Levi Yitzchak, comes up to Heaven, its provenance is scrutinized. Why was this particular amount giv en to charity? Then the relationship to the full amount of the harvest is discovered. There is a ration of ten to one, and the amount given is one tenth of the total. In this way the entire harvest participates in the mitzvah but only in a secondary role. Therefore, if the charity was given with a full heart, the person giving the charity merits that the quality of his donation is elevated. The following year, the entire harvest is elevated from a secondary role to a primary role in the giving of the charit y. The amount of the previous year’s harvest then becomes only one tenth of the new harvest, and the giver becomes wealthy. n Story Unfortunately, there were all too many poor people who circulated among the towns and 1 Re ’eh / [email protected] villages begging for assistance in staving off starvation. -

15 July 2011

www.sajewishreport.co.za Friday, 15 July 2011 / 13 Tammuz, 5771 Volume 15 Number 26 A nation cherishes its favourite son on his 93rd Old stalwarts reminisce - Madiba receives a fond embrace from Esther Barsel, a comrade from the early Struggle days, at a book launch in 2003. SEE PAGE 8 Rotary award for UJ, BGU sign DAVIS: Being ‘apart’ SA’s new info bill Naada Faire Issie Kirsh / 7 new contract / 3 not same as ‘alone’ / 9 seriously flawed / 5 / 12-14 YOUTH / 17 SPORT / 20 LETTERS / 15 CROSSWORD & SUDOKU / 18 COMMUNITY BUZZ / 6 WHAT’S ON / 18 2 SA JEWISH REPORT 15 - 22 July 2011 PARSHA OF THE WEEK SHABBAT AND FAST TIMES July 15/13 Tammuz Fast of Tammuz/Shivah Assar be Published by July 16/14 Tammuz Tammuz S A Jewish Report (Pty) Ltd, Does Judaism sanction July 19/17 Tammuz PO Box 84650, Greenside, 2034 Pinchas Tel: (011) 023-8160 religious fanaticism? Starts Ends Starts Ends Fax: (086) 634-7935 17:16 18:07 Johannesburg 05:40 17:53 Johannesburg Printed by Caxton Ltd 17:37 18:32 Cape Town 06:29 18:16 Cape Town 16:56 17:49 Durban 05:33 17:34 Durban EDITOR - Geoff Sifrin 17:17 18:09 Bloemfontein 05:52 17:55 Bloemfontein [email protected] PARSHAT PINCHAS 17:09 18:03 Port Elizabeth 06:00 17:47 Port Elizabeth 17:02 17:56 East London 05:50 17:40 East London COMMERCIAL MANAGER Rav Eitan Bendavid Sue Morris Yeshiva of Cape Town [email protected] Moderation is key to Joe Baron’s 100 Sub-Editor - Paul Maree DOES JUDAISM sanction religious fanaticism? Parshat Pinchas appears to answer in the affirmative. -

SA-SIG Newsletter P Ostal S Ubscription F

-SU A-SIG U The journal of the Southern African Jewish Genealogy Special Interest Group http://www.jewishgen.org/SAfrica/ Editor: Colin Plen [email protected] Vol. 14, Issue 1 December 2013 InU this Issue President’s Message – Saul Issroff 2 Editorial – Colin Plen 3 Meir (Matey) Silber 4 South African Jews Get Their Master Storyteller – Adam Kirsch 5 A New Diaspora in London – Andrew Caplan 8 Inauguration of Garden Route Jewish Association as SAJBD affiliate 11 From Lithuania to Mzansi: A Jewish Life – Walter and Gordon Stuart 12 Preserving our Genealogy Work for Posterity – Barbara Algaze 13 The Dunera Boys 15 2013 Research Grant Recipients for IIJG 16 New Items of Interest on the Internet – Roy Ogus 17 Editor’s Musings 20 Update on the Memories of Muizenberg Exhibition – Roy Ogus 22 New Book – From the Baltic to the Cape – The Journey of 3 Families 23 Book Review – A Dictionary of Surnames – Colin Plen 24 Letters to the Editor 25 © 2013 SA-SIG. All articles are copyright and are not to be copied or reprinted without the permission of the author. The contents of the articles contain the opinions of the authors and do not reflect those of the Editor, or of the members of the SA-SIG Board. The Editor has the right to accept or reject any material submitted, or edit as appropriate. PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE The Southern Africa Jewish Genealogy In August I attended the annual IAJGS conference in Boston. I think about 1200 people were there and Special Interest Group (SA-SIG) I was told that several hundred watched the sessions The purpose and goal of the Southern Africa Special live using a new on-line streaming system. -

Free Mover Clinical Clerkships

FREE MOVER CLINICAL CLERKSHIPS Students interested in spending a clerkship activity abroad without participating in the Erasmus+ programs can enroll as Free-Movers (Fee-paying Visiting Students or Independent Students or Contract Students) at some foreign University hospitals where they can attend clinical rotations. The Free-Mover Clinical Clerkship Period is an optional part of the medical course and as such must be accounted for. Students not willing to participate still have to attend clinical rotations at the University of Milan. The Clerkship abroad represents a mutual contract between Supervisor and Student and is subject to supervision by the Faculty. In this document, there is the list of possible destinations and university hospitals in which the clinical clerkship period can be performed. For some of the destinations, students are advised to clearly declare their student status, as they may be allowed to participate only as observers and not and interns. 1 AFRICA Egypt Ethiopia Benin Botswana IvoryCoast Ghana Cameroon Kenya Libya Morocco Namibia Nigeria Rwanda Zambia Senegal Sudan SouthAfrica Tanzania Tunisia Uganda Zimbabwe ASIA China India Indonesia Japan Cambodia Malaysia Mongolia Nepal Philippines Singapore SriLanka SouthKorea Taiwan Thailand Vietnam 2 THE MIDDLE EAST Bahrain Iran Israel Jordan Qatar Lebanon Oman Palestine SaudiArabia Syria United Arab Emirates OCEANIA Australia Adelaide Canberra Melbourne Newcastle NewSouthWales Perth Queensland Sydney Tasmania New Zealand EUROPE Belgium Bosnia-Herzigowina Bulgaria Denmark -

Inside This Issue

PAM GOLDING ON MAIN NOW LETTING Locate your office in Kenilworth. Peter Golding 082 825 5561 | Teresa Cook 079 527 0348 Office: 021 426 4440 www.pamgolding.co.za/on-main VOLUME 31 No 10 NOVEMBER 2014 /5775 www.cjc.org.za An interview with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu By Shlomo Cesana, Gonen Ginat, and Amos Regev/JNS.org In this interview with Israel Hayom objective, meaning achieving lasting commander and a bad ahead of Rosh Hashanah, Prime peace and quiet by re-establishing commander, is that Minister Benjamin Netanyahu shared deterrence via dealing [Hamas] a massive a good commander his perspective and strategy, and blow. What happens if they try again? They knows how to achieve analysed the changing realities in the will be dealt a doubly debilitating blow — the declared goals for a Middle East. and they know it.” lesser price. We would Why didn’t Israel vanquish Hamas? have ended up with the Israel Hayom: Is Israel doing better or he answer to that question is same result, only with a worse than it was doing on the eve of Rosh “Tvery complex and it entails a much heavier price, and Hashanah last year? variety of considerations. One of those I don’t want to elaborate enjamin Netanyahu: “We are doing considerations is a spatial consideration, further.” Bbetter while facing a harsher reality. which cannot be ignored. We have Hamas How influential was the The reality around us is that radical Islam in the south, al-Qaeda and the Nusra IDF in preventing a wider is marching forward on all fronts. -

The Further Reforming of Conservative Judaism

The Further Reforming of Conservative Judaism in this issue ... THE JEWISH OBSERVER (ISSN 002]-6615) is published monthly, except July and August, by the Changes in Perspective Through Torah Encounters ........ 6 Agudath Israel of America, 5 Beekman Street, New York, N.Y. The Sunday Night Class, Hillel Belsky ..•.....•.•.... 7 10038. Second class postage paid The Joyful Light, Amos Keinen ........•.••....••••.• 9 at New York, N.Y. Subscription $15.00 per year; two years, $27.00; Concerns of a Parent, Harvey S. Hecker . ...•..••.•..• 10 three years. $36.00 outside of the United States, US funds only. "Dear Mom," Molly, Moshe and I .............•.••.. 13 $20.00 in Europe and Israel. $25.00 in So. Africa and Australia. Single The Age of Teshuva, a review article ..••.•..•..•••.. 14 copy, $2.00. Send address changes Return to The Jewish Observer, 5 Beek man St., N.Y. N.Y. 10038. Printed Pathways in the U.S.A. Our Miraculous World With Perfect faith HABnt N1ssoN WoLPJN Editor The further Reforming of Conservative Judaism, Nisson Wolpin .................................•••••.. 17 Editorial Board The Critical Parent's Guidebook, Avi Shulman .•.•..•.••••.• 20 OR. ERNST BoDENHrtMER Chairman The "Chaver," Yisroel Miller ...•....•.....•.....•.•..•... 25 RABBI NATHAN BULMAN RABBI josrrtt Eu ... s Saddiq of the Sahara, Nehama Consuelo Nahmoud . ......•.•..• 28 Josu'H fRIEDENSON RABBI MOSHE SHERER Books in Review ...................................... 33 Management Board The Wisdom in the Hebrew Alphabet NAFTOU HIRSCH !SAA( K!RZNER Chumash Bereshith (Three Sidros); NACHUM 5TF.!N A Linear Translation Business Manager Letter to a Soviet Jew, a poem by Varda Branfman .......••..• 35 PESACH H. KONSTAM Second Looks at the Jewish Scene T Hr Jrw1sH OesERVrR does not assume responsibility for the The Dioxin Connection ........................ -

Adult Education in Israel the Jews

CHESHVAN, 5735 I OCTOBER, 1974 VOLUME X, NUMBER 4 rHE SIXTY FIVE CENTS Adult Education in Israel -Utopian dream or a feasible program? The Jews: A People of ''Shevatim'' -for divisiveness or unification? Moshiach Consciousness -a message from the Chafetz Chaim The Jewish State -beginnings of redemption or a Golus phenomenon? The Seattle Legacy -heirs of a childless couple THE JEWISH QBSERVER in this issue ... SPREADING A NET OF TORAH, Mordechai David Ludmir as told to Nisson Wolpin ..................................... 3 THE JEWS - A PEOPLE OF "SHEVATIM," Shabtai Slae ........................ ............................. ........... 6 THE CHOFETZ CHAIM ON MOSHIACH CONSCIOUSNESS. Elkanah Schwartz ............... ....................... 9 THE END OF GOLUS? or THE BEGINNING OF GEULAH?, Moshe Schonfeld ..................................... ... 12 THE JEWISH OBSERVER is published THE SEATTLE LEGACY, Nissan Wolpin ................. ............. 18 monthly, except July and August, by the Agudath Israel of Amercia, 5 Beekman St., New York, N. Y. CRASH DIET, Pinchas Jung ....... ······················ ............. 23 10038. Second class postage paid at New York, N. Y. Subscription: $6.50 per year; Two years, $11.00; "HIS SEAL IS TRUTH" .......................................................... 25 Three years $15.00; outside of the United States $7 .50 per year. Single copy sixty~five cents. LETTERS TO THE EDITOR ................................................... 28 Printed in the U.S.A. RABBI NISSON WOLPIN Editor GIVE A SPECIAL GIFT TO SOMEONE SPECIAL Editorial Board DR. ERNST L. BODENHEIMER THE JEWISH OBSERVER Chairman 5 Beekman Street / New York, N. Y. 10038 RABBI NATHAN BULMAN RABBI JOSEPH ELIAS 0 ONE YEARi $6.50 0 TWO YEARS: a $13 value, only $11 JOSEPH FRIEDENSON D THREE YEARS: a $19.50 , .. aJue, 011/y $15 RABBI Y AAKOV JACOBS RABBI MOSHE SHERER Send Magazine to: Fro1n: Na1ne.............. -

List of Section 18A Approved PBO's V1 0 7 Jan 04

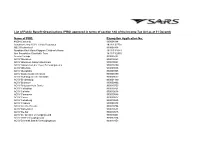

List of Public Benefit Organisations (PBO) approved in terms of section 18A of the Income Tax Act as at 31 December 2003: Name of PBO: Exemption Application No: 46664 Concerts 930004984 Aandmymering ACVV Tehuis Bejaardes 18/11/13/2738 ABC Kleuterskool 930005938 Abraham Kriel Maria Kloppers Children's Home 18/11/13/1444 Abri Foundation Charitable Trust 18/11/13/2950 Access College 930000702 ACVV Aberdeen 930010293 ACVV Aberdeen Aalwyn Ouetehuis 930010021 ACVV Adcock/van der Vyver Behuisingskema 930010259 ACVV Albertina 930009888 ACVV Alexandra 930009955 ACVV Baakensvallei Sentrum 930006889 ACVV Bothasig Creche Dienstak 930009637 ACVV Bredasdorp 930004489 ACVV Britstown 930009496 ACVV Britstown Huis Daniel 930010753 ACVV Calitzdorp 930010761 ACVV Calvinia 930010018 ACVV Carnarvon 930010546 ACVV Ceres 930009817 ACVV Colesberg 930010535 ACVV Cradock 930009918 ACVV Creche Prieska 930010756 ACVV Danielskuil 930010531 ACVV De Aar 930010545 ACVV De Grendel Versorgingsoord 930010401 ACVV Delft Versorgingsoord 930007024 ACVV Dienstak Bambi Versorgingsoord 930010453 ACVV Disa Tehuis Tulbach 930010757 ACVV Dolly Vermaak 930010184 ACVV Dysseldorp 930009423 ACVV Elizabeth Roos Tehuis 930010596 ACVV Franshoek 930010755 ACVV George 930009501 ACVV Graaff Reinet 930009885 ACVV Graaff Reinet Huis van de Graaff 930009898 ACVV Grabouw 930009818 ACVV Haas Das Care Centre 930010559 ACVV Heidelberg 930009913 ACVV Hester Hablutsel Versorgingsoord Dienstak 930007027 ACVV Hoofbestuur Nauursediens vir Kinderbeskerming 930010166 ACVV Huis Spes Bona 930010772 ACVV -

A Day Packed Full of Inspiration Personal Growth & Spirituality

CHASSIDUS SUMMIT2018 A day packed full of inspiration personal growth & spirituality Top Local and International Speakers Morning and Evening Programme Snacks and Coffee Throughout the Day SUNDAY 12 AUGUST 2018 ROSH CHODESH ELUL 5778 THE CAPITAL ON THE PARK 101 KATHERINE STREET SANDTON COST: R100 BOOK YOUR SEAT TODAY Call 011 440 6600 or email [email protected] PROGRAMME 9am Coffee and Snacks 9:15am Session One Open Soul Surgery Rabbi Yossi Paltiel ROOM 1 ROOM 10:15am Session Two Doing More by Being Less Rabbi Levy Wineberg ROOM 2 ROOM From Exile to Redemption Rabbi Noam Wagner ROOM 3 ROOM Nothing is More Whole Than a Broken Heart Mrs Simcha Youngworth (Women Only) ROOM 4 ROOM 11:15am Session Three Chassidus: Spiritual Strategies to Overcome Stress Rabbi Ari Shishler ROOM 2 ROOM The Call of the Shofar Rabbi Nesanel Schochet ROOM 3 ROOM Regret & Renewal: Transforming my Past into a Better Future Rebbetzin Estee Stern (Women Only) ROOM 4 ROOM 7:15pm Evening Session Chassidus Unplugged Rabbi Yossi Paltiel and Friends - “FARBRENGEN” ROOM 1 ROOM Cecil Skotnes, Conrad Botes, Art & antiques auction on 4 August 2018 9:30am carved and reverse glass painting painted panel using oil-based paints Items wanted for forthcoming auctions R200 000 – R300 000 R20 000 – R30 000 View upcoming auction highlights at www.rkauctioneers.co.za 011 789 7422 • 083 675 8468 • 12 Allan Road, Bordeaux, Johannesburg south african n Volume 22 – Number 27 n 27 July 2018 n 15 Av 5778 The source of quality content, news and insights t www.sajr.co.za Christians march to Union Buildings, shouting “Viva Israel!” NICOLA MILTZ The event was almost called off following Israelis teach their children to love, to be present at the rally not to take sides in the the late-notice and unexpected cancellation innovative.” Palestinian-Israeli conflict, but instead, housands of Christians took to the of the venue hire by Freedom Park, where the He challenged the PA to encourage the to listen to both sides and encourage streets in Pretoria on Wednesday in rally was scheduled to take place (see page 2). -

Download the August 2012 Issue

We are proud of the service we have provided to Trustees and Owners of Bodies Corporate and Homeowners Associations over 15 years. If we don’t already manage your apartment block or complex, we would like to. CONTACT Mike Morey TEL (021) 426 4440 FAX (021) 426 0777 EMAIL [email protected] VOLUME 29 No 7 AUGUST 2012 5772 www.cjc.org.za Jerusalem and Pretoria — The Chronicle16082_Earspace for needs Jewish Chronicle FA.indd your 1 support!2011/08/19 10:40 AM a relationship under pressure? The Cape Jewish Chronicle is sent to every Jewish By Moira Schneider household in the Western Cape free of charge. However, we need voluntary subscriptions to ensure that this continues. he Chronicle has always been able to maintain this Tmandate of being sent to every family at no cost; and this is in a large part thanks to the many community members who pay annual voluntary subscriptions. However, we have recently noticed a significant drop in subscriptions, which endangers the Chronicle’s mandate to be a free publication, and to continue in its current format. Level of 2012 We therefore appeal to every community member to support v o l u n t a r y the Chronicle in your own small way. It is an opportunity to subscriptions received to contribute to the community, and to ensure that the Chronicle date. continues to arrive in your post box every month! If you paid your subscription last year, this is the time to repeat that generosity; and if you have never paid it before, it’s not too late to start! Alan Fischer (Cape Town coordinator of Fairplay SA), Mike Anisfeld (AIPAC activist), Gary Eisenberg (Chairman Cape SAJBD legal sub-committee), Li Boiskin (Cape SAJBD Chairman) Thank you to everyone who has contributed thus far — your generosity and Mary Kluk (SAJBD National Chairman) all spoke at the general meeting.