Promise, Trust and Betrayal: Costs of Breaching an Implicit Contract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sunrise Beverage 2021 Craft Soda Price Guide Office 800.875.0205

SUNRISE BEVERAGE 2021 CRAFT SODA PRICE GUIDE OFFICE 800.875.0205 Donnie Shinn Sales Mgr 704.310.1510 Ed Saul Mgr 336.596.5846 BUY 20 CASES GET $1 OFF PER CASE Email to:[email protected] SODA PRICE QUANTITY Boylan Root Beer 24.95 Boylan Diet Root Beer 24.95 Boylan Black Cherry 24.95 Boylan Diet Black Cherry 24.95 Boylan Ginger Ale 24.95 Boylan Diet Ginger Ale 24.95 Boylan Creme 24.95 Boylan Diet Creme 24.95 Boylan Birch 24.95 Boylan Creamy Red Birch 24.95 Boylan Cola 24.95 Boylan Diet Cola 24.95 Boylan Orange 24.95 Boylan Grape 24.95 Boylan Sparkling Lemonade 24.95 Boylan Shirley Temple 24.95 Boylan Original Seltzer 24.95 Boylan Raspberry Seltzer 24.95 Boylan Lime Seltzer 24.95 Boylan Lemon Seltzer 24.95 Boylan Heritage Tonic 10oz 29.95 Uncle Scott’s Root Beer 28.95 Virgil’s Root Beer 26.95 Virgil’s Black Cherry 26.95 Virgil’s Vanilla Cream 26.95 Virgil’s Orange 26.95 Flying Cauldron Butterscotch Beer 26.95 Bavarian Nutmeg Root Beer 16.9oz 39.95 Reed’s Original Ginger Brew 26.95 Reed’s Extra Ginger Brew 26.95 Reed’s Zero Extra Ginger Brew 26.95 Reed’s Strongest Ginger Brew 26.95 Virgil’s Zero Root Beer Cans 17.25 Virgil’s Zero Black Cherry Cans 17.25 Virgil’s Zero Vanilla Cream Cans 17.25 Virgil’s Zero Cola Cans 17.25 Reed’s Extra Cans 26.95 Reed’s Zero Extra Cans 26.95 Reed’s Real Ginger Ale Cans 16.95 Reed’s Zero Ginger Ale Cans 16.95 Maine Root Mexican Cola 28.95 Maine Root Lemon Lime 28.95 Maine Root Root Beer 28.95 Maine Root Sarsaparilla 28.95 Maine Root Mandarin Orange 28.95 Maine Root Spicy Ginger Beer 28.95 Maine Root Blueberry 28.95 Maine Root Lemonade 12ct 19.95 Blenheim Regular Ginger Ale 28.95 Blenheim Hot Ginger Ale 28.95 Blenheim Diet Ginger Ale 28.95 Cock & Bull Ginger Beer 24.95 Cock & Bull Apple Ginger Beer 24.95 Double Cola 24.95 Sunkist Orange 24.95 Vernor’s Ginger Ale 24.95 Red Rock Ginger Ale 24.95 Cheerwine 24.95 Diet Cheerwine 24.95 Sundrop 24.95 RC Cola 24.95 Nehi Grape 24.95 Nehi Orange 24.95 Nehi Peach 24.95 A&W Root Beer 24.95 Dr. -

The Reluctant Famulus # 83 September/October 2011 Thomas D

83 The Reluctant Famulus # 83 September/October 2011 Thomas D. Sadler, Editor/Publisher, etc. 305 Gill Branch Road, Owenton, KY 40359 Phone: 502-484-3766 E-mail: [email protected] Contents Introduction, Editor 1 Old Kit Bag, Robert Sabella 4 Indian Battle, Editor 6 News Bits, Editor 7 Rat Stew, Gene Stewart 8 Grave Marker, Editor 10 Serpent Mound, Al Byrd 11 Old Alabama News, Editor 14 Indiana-ania, Matt Howard 15 The Eyes Say It All, Sheryl Birkhead 19 Oh Dear, Matt Howard 22 Things I Discover, Editor 23 Iguanacon,* Taral Wayne 24 Letters of Comment 30 The End, Editor 45 Artwork G. Thomas Doubrley Front cover Helen Davis 11, 12 Kurt Erichsen 4, 8 Brad Foster 38, Back Cover Alexis Gilliland 6, 30, 34, 42 T. D. Sadler 10 (bottom), 21 Spore & Toe Toe Hodges 7, 32, 36, 40, 44 Internet 2, 10 (top) Indianapolis Star 15 (Lcol.), 17, 18 Indiana State Library 15 (R col.) Postcard 16 Taral Wayne 24, 29 * Reprinted from DQ 9, 1978 The Reluctant Famulus is a product of Strange Dwarf Publications. Many of the comments expressed herein are sole- ly those of the Editor/Publisher and do not necessarily reflect the thoughts of any sane, rational persons who know what they are doing and have carefully thought out beforehand what they wanted to say. Material not written or pro- duced by the Editor/Publisher is printed by permission of the various writers and artists and is copyright by them and remains their sole property. Permission is granted to any persons who wish to reprint material presented herein, pro- vided proper and due credit is given both to the author/artist who produced the material and to the original publication in which it appeared. -

BOTTLE TALK Readers

RALEIGH BOTTLE CLUB NEWS LETTER Editor: Marshall Clements October, 2008 2008 BOTTLE CLUB OFFICERS PRESIDENT ____________________David Bunn VICE PRESIDENT ______________ Barton Weeks SECRETARY / TREASURER ______Robert Creech HALLOWEEN HAVE A HAPPY Decorated MAKERS MARK Whiskey Bottle 1 The RBC Gallery Sterling Mann presented a few of his unusual and rare "throw away" bottles. These are just a few of Sterling's vast collection of 'non-returnable' bottles. Sterling also collects soda advertisement that pertains to his collection. Contrary to what you might think there is very little advertisement for 'throw away' sodas. Thanks to Sterling for another great presentation. Five unusual, colorful, and rare 'throw away' Cokes 2 The bottles shown on this page are AND 'THE MANN' PLAYS ON... all 'no return' bottles that are extremely difficult to find due to their unique colors and designs. These are just a few more of Sterling's great collection of "Throw away" sodas. Clear and pale green DOUBLE COLA Amber and Emerald FRESCA Emerald and Clear FANTA Amber and Clear TAB 3 RALEIGH BOTTLE CLUB 2008 RALEIGH BOTTLE CLUB Bottles and Collectibles Show 2008 Shawn McLain looking for a bargain RBC Member Vernon Freeman arranges his table 4 RBC member Ron Hinsley shows off his display case RBC members Robert Creech and George Poniros discuss bottles Anita and Jerry Cullom selling bottles and tobacco items 5 RBC member Whitt Stallings closes another big deal RBC member John Young making a sale RBC members Dean Haley and Vernon Creech doing some business 6 Terry Faulk and Tim Waller 'chewing the fat' with insulator man Doug Williams 7 John McAuley unpacks as Jimmy Wood scans the crowd for customers 8 John McAulay sold this nice five gallon crock to none other than Marvin Crocker. -

The 2017 Beverage Marketing Directory Copyright Notice

About this demo This demonstration copy of The Beverage Marketing Directory – PDF format is designed to provide an idea of the types and depth of information and features available to you in the full version as well as to give you a feel for navigating through The Directory in this electronic format. Be sure to visit the Features section and use the bookmarks to click through the various sections and of the PDF edition. What the PDF version offers: The PDF version of The Beverage Marketing Directory was designed to look like the traditional print volume, but offer greater electronic functionality. Among its features: · easy electronic navigation via linked bookmarks · the ability to search for a company · ability to visit company websites · send an e-mail by clicking on the link if one is provided Features and functionality are described in greater detail later in this demo. Before you purchase: Please note: The Beverage Marketing Directory in PDF format is NOT a database. You cannot manipulate or add to the information or download company records into spreadsheets, contact management systems or database programs. If you require a database, Beverage Marketing does offer them. Please see www.bmcdirectory.com where you can download a custom database in a format that meets your needs or contact Andrew Standardi at 800-332-6222 ext. 252 or 740-314-8380 ext. 252 for more information. For information on other Beverage Marketing products or services, see our website at www.beveragemarketing.com The 2017 Beverage Marketing Directory Copyright Notice: The information contained in this Directory was extensively researched, edited and verified. -

“List of Companies/Llps Registered During the Year 1982”

“List of Companies/LLPs registered during the year 1982” Note: The list include all companies/LLPs registered during this period irrespective of the current status of the company. In case you wish to know the current status of any company please access the master detail of the company at the MCA site http://mca.gov.in Sr. No. CIN/FCRN/LLPIN/FLLPIN Name of the entity Date of Incorporation 1 U45200MH1982PLC025999 ASIATIC PROPERTIES LTD 1/1/1982 2 U33110MH1982PTC026004 CROWN WATCHES PVT LTD 1/1/1982 3 U74899DL1982PTC012932 ANURUP EXPORTS PRIVATE LIMITED 1/1/1982 4 U15127TN1982PTC009153 AGRO PRODUCE BROKERS PRIVATE LIMITED 1/1/1982 5 U18209TN1982PTC009154 AMBUR LEATHERS PVT LTD 1/1/1982 6 U33111TN1982PTC009156 DVM REFRIGERATION & AIR CONDITIONING PVT LTD 1/1/1982 7 U63090GJ1982PTC004944 ARIHANT TRAVELS PVT LTD 1/1/1982 8 U92112OR1982PTC001025 DYNAMIC STUDIOS PVT LTD 1/1/1982 9 U55101KA1982PTC004571 KOMARALA HOTELSANDRESORTS PRIVATE LIMITED 1/1/1982 10 U85110KA1982PTC004577 KOR INVESTMENTS PRIVATE LIMITED 1/1/1982 11 U18101KA1982PTC004579 HARWOOD GARMENTS PRIVATE LIMITED 1/1/1982 12 U65993KA1982PTC004576 KUSHAL INVESTMENTS PRIVATE LIMITED 1/1/1982 13 U24299PB1982PTC004789 KISHORE CHEMICALS PVT LTD 1/1/1982 14 U24231GJ1982PTC004946 KISAN BROTHERS PVT LTD 1/1/1982 15 U52324MH1982PTC026001 G GANGADAS SHSH AND SONS PVT LTD 1/1/1982 16 U01220MH1982PTC025998 THE EQUUS STUD PVT LTD 1/1/1982 17 U26941GJ1982PTC004943 VEKMONS PRIVATE LIMITED 1/1/1982 18 U00313KA1982PTC004573 MAPLE PLAST PRIVATE LIMITED 1/1/1982 19 U01135GJ1982PTC004942 MAHENDRA AND MAHENDRA SEEDS PVT LTD 1/1/1982 20 U24231GJ1982PTC004945 OPAL PROCESS SUPPLIER PRIVATE LIMITED 1/1/1982 21 U26999UP1982PLC005517 PREMIER VINYL FLOORING LIMITED. -

CPY Document

THE COCA-COLA COMPANY 795 795 Complaint IN THE MA TIER OF THE COCA-COLA COMPANY FINAL ORDER, OPINION, ETC., IN REGARD TO ALLEGED VIOLATION OF SEC. 7 OF THE CLAYTON ACT AND SEC. 5 OF THE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION ACT Docket 9207. Complaint, July 15, 1986--Final Order, June 13, 1994 This final order requires Coca-Cola, for ten years, to obtain Commission approval before acquiring any part of the stock or interest in any company that manufactures or sells branded concentrate, syrup, or carbonated soft drinks in the United States. Appearances For the Commission: Joseph S. Brownman, Ronald Rowe, Mary Lou Steptoe and Steven J. Rurka. For the respondent: Gordon Spivack and Wendy Addiss, Coudert Brothers, New York, N.Y. 798 FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION DECISIONS Initial Decision 117F.T.C. INITIAL DECISION BY LEWIS F. PARKER, ADMINISTRATIVE LAW JUDGE NOVEMBER 30, 1990 I. INTRODUCTION The Commission's complaint in this case issued on July 15, 1986 and it charged that The Coca-Cola Company ("Coca-Cola") had entered into an agreement to purchase 100 percent of the issued and outstanding shares of the capital stock of DP Holdings, Inc. ("DP Holdings") which, in tum, owned all of the shares of capital stock of Dr Pepper Company ("Dr Pepper"). The complaint alleged that Coca-Cola and Dr Pepper were direct competitors in the carbonated soft drink industry and that the effect of the acquisition, if consummated, may be substantially to lessen competition in relevant product markets in relevant sections of the country in violation of Section 7 of the Clayton Act, as amended, 15 U.S.C. -

Soda Handbook

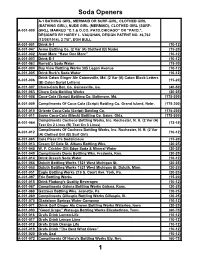

Soda Openers A-1 BATHING GIRL, MERMAID OR SURF-GIRL, CLOTHED GIRL (BATHING GIRL), NUDE GIRL (MERMAID), CLOTHED GIRL (SURF- A-001-000 GIRL), MARKED “C.T.& O.CO. PATD.CHICAGO” OR “PATD.”, DESIGNED BY HARRY L. VAUGHAN, DESIGN PATENT NO. 46,762 (12/08/1914), 2 7/8”, DON BULL A-001-001 Drink A-1 (10-12) A-001-047 Acme Bottling Co. (2 Var (A) Clothed (B) Nude) (15-20) A-001-002 Avon More “Have One More” (10-12) A-001-003 Drink B-1 (10-12) A-001-062 Barrett's Soda Water (15-20) A-001-004 Bay View Bottling Works 305 Logan Avenue (10-12) A-001-005 Drink Burk's Soda Water (10-12) Drink Caton Ginger Ale Catonsville, Md. (2 Var (A) Caton Block Letters A-001-006 (15-20) (B) Caton Script Letters) A-001-007 Chero-Cola Bot. Co. Gainesville, Ga. (40-50) A-001-063 Chero Cola Bottling Works (20-25) A-001-008 Coca-Cola (Script) Bottling Co. Baltimore, Md. (175-200) A-001-009 Compliments Of Coca-Cola (Script) Bottling Co. Grand Island, Nebr. (175-200) A-001-010 Oriente Coca-Cola (Script) Bottling Co. (175-200) A-001-011 Sayre Coca-Cola (Block) Bottling Co. Sayre, Okla. (175-200) Compliments Cocheco Bottling Works, Inc. Rochester, N. H. (2 Var (A) A-001-064 (12-15) Text On 2 Lines (B) Text On 3 Lines) Compliments Of Cocheco Bottling Works, Inc. Rochester, N. H. (2 Var A-001-012 (10-12) (A) Clothed Girl (B) Surf Girl) A-001-065 Cola Pleez It's Sodalicious (15-20) A-001-013 Cream Of Cola St. -

A Comparative Study on Orange Flavoured Soft Drinks with Special Reference to Mirinda, Fanta and Torino in Ramanathapuram District

Vol. 3 No. 2 October 2015 ISSN: 2321 – 4643 3 A COMPARATIVE STUDY ON ORANGE FLAVOURED SOFT DRINKS WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO MIRINDA, FANTA AND TORINO IN RAMANATHAPURAM DISTRICT M.Abbas Malik Associate Professor & Head, Department of Management Studies, Mohamed Sathak Engineering College, Kilakarai – 623 806 Abstract Soft drinks market in India has been grown in size with the entry of the Multi National Corporations. At present soft drink market is one of the most competitive markets in India which spends crores of rupees in advertisement and other promotionary activities. A bottle drink consumers have a wide range of brands at their disposal. It is difficult for a consumer to stick on to a particular brand of flavour unless the consumer satisfaction level is very high. Orange flavoured soft drink is one of the popular segments in soft drink. In India Mirinda and Fanta are the major orange flavoured soft drinks. But in this area under study (Ramanathapuram District) Torino is a local brand is having very good presence and influences. So, researcher wanted to know their present market share of Mirinda, Fanta and Torino. The objectives of the Study are: 1. To estimate the market share of major orange flavoured soft drink brands under the area of study. 2. To study the Socio-economic profile by using orange flavoured drinks. 3. To find the most preferred orange flavour soft drink in the market. 4. To determine the reason for preferring a particular brand of orange flavoured soft drink. 5. To make suggestions based on the findings of the study. -

Promise, Trust and Betrayal: Costs of Breaching an Implicit Contract

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Levy, Daniel; Young, Andrew T. Working Paper Promise, Trust and Betrayal: Costs of Breaching an Implicit Contract Suggested Citation: Levy, Daniel; Young, Andrew T. (2019) : Promise, Trust and Betrayal: Costs of Breaching an Implicit Contract, ZBW – Leibniz Information Centre for Economics, Kiel, Hamburg This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/197001 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Promise, Trust and Betrayal: Costs of Breaching an Implicit Contract* Daniel Levy** Department of Economics, Bar-Ilan University Ramat-Gan 52900, ISRAEL, Department of Economics, Emory University Atlanta GA, 30322, USA, and Rimini Center for Economic Analysis, ITALY [email protected] Andrew T. -

The History and Bottles of the Soft Drink Industry in El Paso, Texas, 1881-2000

Bottles on the Border: The History and Bottles of the Soft Drink Industry in El Paso, Texas, 1881-2000 Chapters 1-4 © Bill Lockhart 2010 [Revised Edition – Originally Published Online in 2000] Chapter 1 General History of El Paso Bottlers The soft drink industry was already long established in Texas when El Paso’s first bottler opened its doors. Dr. Thomas Mitchell, and English physician, opened the first soda fountain in Houston in 1839. It was 27 years later when J. J. C. Smith established a “mineral water manufactory” in 1866, again in Houston. By 1880, Texas contained 11 bottling plants, and that number had grown to 42 in 1890 (Dunagan 2002). Soft drink bottling in El Paso began on April 1, 1881 with the opening of Houck & Dieter, although Coffin & Co. advertised soda bottling “kits” in 1881 and may have sold them much earlier. The firm was not, however, a bottler, as such. Although Houck & Dieter’s primary occupation was the wholesale distribution of liquor and wine, the firm realized the need for chasers and incidentally provided non-alcoholic drinks for the desert population. Although G. Edwin Angerstein briefly challenged their supremacy in 1883, the liquor dealers controlled the soft drink industry in the city until shortly before 1910. At that time, they were met by three noteworthy opponents: Martin R. Sweeney (later to organize Woodlawn Bottling Company) in 1905; Purity Bottling and Manufacturing Company (owned and operated by Lawrence Gardner) in 1906; and Magnolia Bottling Company (founded by Hope Smith) in 1908. Although Gardner claimed singlehanded victory over the liquor establishment, the other two were obviously generating impressive sales as well. -

Ftc Volume Decision 91

" " " " " " .. .... .." " " " " " " "" " " " " " , " , " , " ...- - . .." ..- 548 FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION DECISIONS Initial Decision 91 F. will receive a fair and equitable compensation for the investment has made in developing his territory" (Smith, Tr. 616). Bottlers can acquire another bottler without the approval of "Coca-Cola" through a stock acquisition (Smith , Tr. 628). " Coca-Cola " if asked, has recom mended that bottlers merge or consolidate where appropriate (Smith Tr. 615-16). However, bottlers are independent businessmen who make their own independent decisions and who frequently a~t contrary to the advice of "Coca-Cola" (Smith, Tr. 615-16). (36) Competition in the Soft Drink Industry Generally 88. There is intense competition in the sale of flavored carbonated soft drinks which stems from the fact that there is a large number of brands available to the consumer in local markets. In 1971, a Neilsen Survey showed that there were 135 different brands of cola flavored soft drinks marketed in food stores (Smith, Tr. 705). In the Washing ton, D. , metropolitan area alone, there are over 30 brands of colas being marketed (Sales, Tr. 1243-1251). In addition to the cola brands more than 20 other brands of flavors such as root beer, orange gingerale, and lemon-lime were being sold in the Washington, D. market (Sales, Tr. 1243, 1255; CX 372; CX 373). In the territory of the Newport News , Virginia bottler of Coca-Cola, between 30 and 40 different brands of orange and grape soft drinks were being marketed (Brown, Tr. 1666). Over 176 different brands of flavored carbonated soft drinks were sold in the territory of The Coca-Cola Bottling Company of New York, Inc. -

Scotch Whisky, They Often Refer to A

Catalogue Family Overview Styles About the Font LL Catalogue is a contemporary a rising demand for novels and ‘news’, update of a 19th century serif font of these fonts emerged as symptom of Catalogue Light Scottish origin. Initially copied from a new culture of mass education and an old edition of Gulliver’s Travels by entertainment. designers M/M (Paris) in 2002, and In our digital age, the particularities Catalogue Light Italic first used for their redesign of French of such historical letterforms appear Vogue, it has since been redrawn both odd and unusually beautiful. To from scratch and expanded, following capture the original matrices, we had Catalogue Regular research into its origins and history. new hot metal types moulded, and The typeface originated from our resultant prints provided the basis Alexander Phemister’s 1858 de- for a digital redrawing that honoured Catalogue Italic sign for renowned foundry Miller & the imperfections and oddities of the Richard, with offices in Edinburgh and metal original. London. The technical possibilities We also added small caps, a Catalogue Bold and restrictions of the time deter- generous selection of special glyphs mined the conspicuously upright and, finally, a bold and a light cut to and bold verticals of the letters as the family, to make it more versatile. Catalogue Bold Italic well as their almost clunky serifs. Like its historical predecessors, LL The extremely straight and robust Catalogue is a jobbing font for large typeface allowed for an accelerated amounts of text. It is ideally suited for printing process, more economical uses between 8 and 16 pt, provid- production, and more efficient mass ing both excellent readability and a distribution in the age of Manchester distinctive character.